calsfoundation@cals.org

Paragould (Greene County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 36°03’26″N 090°30’01″W |

| Elevation: | 291 feet |

| Area: | 31.86 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 29,537 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | March 21, 1883 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

1,666 |

3,324 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

5,248 |

6,306 |

5,966 |

7,079 |

9,668 |

9,947 |

10,639 |

15,248 |

18,540 |

22,017 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

26,113 |

29,537 |

Paragould (Greene County), an Arkansas Community of Excellence and a Main Street Community, is situated atop Crowley’s Ridge. The unique name Paragould is a blend of the names of two highly competitive railroad men, James W. Paramore and Jay Gould, evidencing the importance of railroads in the development of the town.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1815, Benjamin Crowley moved his family from Kentucky to Lawrence County in Arkansas. In December 1821, Crowley crossed the Black and Cache rivers to explore the ridge area that now bears his name. Armed with a War of 1812 land grant, he selected a vacated Delaware Indian site that had developed around a large spring. The county seat was in Crowley’s home until it was moved to Paris, then Gainesville in 1848.

The lowlands of the St. Francis, Cache, and Black rivers slowed settlement in Greene County. In 1849, Congress passed an act intended to reclaim the swamplands. It transferred all the Arkansas swamplands to the state and provided funds for locating, evaluating, and draining.

With a new county seat on an improved road running to Helena (Phillips County), the growth of Gainesville, the drainage activities, and the arrival of land speculators, Greene County finally began to boom in the mid-1850s.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

In 1872, the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad (Missouri Pacific) began service through Arkansas between St. Louis, Missouri, and Texarkana (Miller County). James W. Paramore, president of the Texas-St. Louis Railroad (Cotton Belt) wanted a way to ship Texas cotton to St. Louis and points beyond. In 1877, he made a deal to connect his Texas railroad line with the Iron Mountain at Texarkana. However, at that time the “Palmer and Sullivan” railroad system was being developed in Mexico. Paramore’s directors voted to expand their Texas railroad line to join the Mexican railway, giving St. Louis a direct connection through Arkansas and Texas to Mexico City. Jay Gould, who gained control of the Iron Mountain Railroad in 1880, learned that Paramore’s Texas-St. Louis Railroad was licensed to build a cheaper narrow-gauge line through Arkansas to Texas. Gould constructed a regular-gauge line to parallel Paramore’s route. It ran through Greene County toward Helena. The railroads crossed six miles south of Gainesville. After the community that grew around the crossing (later called Parmley) gained a post office, the postmaster, Marcus Meriwether, named the town Paragould without any official approval, deriving the name from Paramore and Gould.

Paragould became a thriving community. Investors knew that the forests covering eastern Arkansas contained one of the few remaining quality hardwood sources in the nation. The availability of rail transportation brought about a surge of large corporate investments. Men abandoned their farms and flocked to work in the timber mills and factories that had been hurriedly constructed around the area. Merchants and professionals followed.

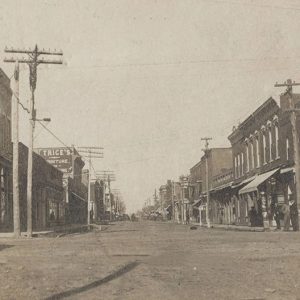

Merchants first located on Front Street behind the present buildings facing west on Pruett Street. First to open were a tent saloon, a fish business, a tent hotel, a bakery, a blacksmith shop, and a fruit stand. A hardware store and a general store opened on Main at the Pruett Street intersection. Soon, the area had more merchants than Gainesville, the county seat.

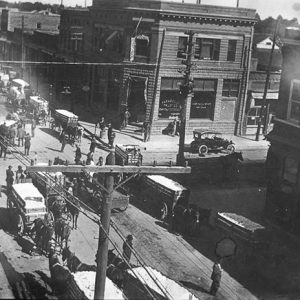

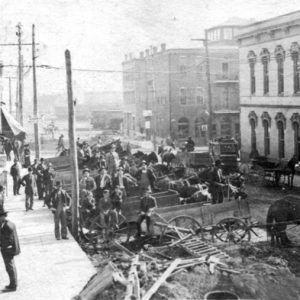

Within a year, Pruett Street became the main business location in the new town. In spite of the street’s thick, slimy mire, several Gainesville businessmen opened stores there. When the county clerk, the Reverend D. B. Warren, moved his newspaper, the Press, to Paragould in 1884, it marked the beginning of Gainesville’s demise. After a county-wide referendum in September 1884, Paragould became the county seat, although it had no city government. The Paragould City Council began to function in May 1885. One of the first significant acquisitions approved by the council was Linwood Cemetery. The new county courthouse was completed in 1888; the Paragould City Hall and adjacent fire house were completed in 1890. Having noted that fire swept rapidly through the wooden buildings in downtown Gainesville in 1890, the Paragould council passed an ordinance requiring that all new buildings in the main part of town be constructed of brick. An electric light plant went into operation in 1891, telephone service appeared in 1896, and a municipally owned water works opened in 1898. By 1896, Paragould had six miles of gravel streets; it was 1912 before the downtown streets were paved.

By 1890, there were fourteen lumber mills in Paragould. Products included both “slack” and “tight” barrel staves, boxes, wood veneer, spokes, dowel pins, caskets, baskets, handles, shingles, and railroad ties. The Wrape Stave and Heading Mill was shipping five million barrels a year, more than any factory in the state. In 1894, that firm shipped more whiskey barrels than any other plant in the world.

Early Twentieth Century

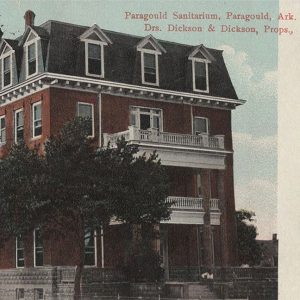

Paragould’s economy was booming at the turn of the new century, mainly because small towns had sprung up in nearby places along the railroads. Paragould became the principal trading center of northeast Arkansas. The city’s infrastructure had been developed to the extent that it could support the demands of new industry and increased population. By 1910, the town had three department stores, an opera house, a hospital, and six banks.

Race relations in Paragould were strained and occasionally violent. Benjamin H. Crowley Jr.—a Paragould lawyer, former Confederate officer, elected state official, and later commander of the state militia—wrote in the December 24, 1909, issue of the Daily Soliphone, “While the population of Greene County is virtually all white, there being less than a score of colored people in the county at this time, and our people are from all sections of the country, all are given an equal chance and a square deal.” However, Crowley was a member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) during the early days of Reconstruction. In his history of Greene County, written in 1906, he made statements clearly supportive of the KKK. For many years black strangers were told by city officials “to leave town before sundown,” and attempts at violently expelling the local black population took place in 1888, 1892, 1899, and 1908. Black railroad crewmen were told they could stay in town as long as they were working, but their activities were limited to where they were boarding overnight. Black children were not provided any form of public education until 1948 when Superintendent Ralph Haizlip made arrangements to bus them to a public school in Jonesboro (Craighead County).

American Legion records reveal that 476 men left Greene County to serve in World War I. At least forty of those men were killed. A white marble war memorial with a five-foot-tall bronze replica of the Statue of Liberty was erected on the courthouse square in 1924. The back of the memorial is inscribed with the names of those men who died.

During Prohibition, the people of Paragould plunged into the boot-legging and free-spirited activities of the era. There is evidence that local businessmen, operating in an atmosphere that favored business, aggressively took advantage of loopholes and non-enforcement of laws during the periods of great prosperity of the 1920s.

But all was not well for the decade. The December 12, 1926, suicide of Ad Bertig, who was involved in several businesses in the area, likely because of heavy operational losses, threatened to start a run on local banks. The failure of the Bertig businesses had a negative impact on the Paragould economy. However, none of the Paragould banks failed as a result of the stock market crash in October 1929. One, the Security Bank and Trust Company, reorganized in 1930. St. Mary’s Catholic Church was constructed in 1935. Although Paragould was remote to many of the major events that caused the Great Depression, factors such as the tremendous slow-down of the nation’s businesses, collapsing farm prices, terrible summer droughts, dust storms and floods (especially the Flood of 1937), and a second depression in 1937 devastated the local economy for over a decade.

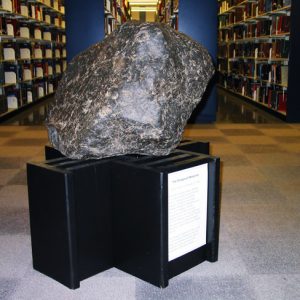

One major event in Paragould proved a brief distraction from the hard times of the Depression. At 4:08 a.m., February 17, 1930, Paragould residents were awakened by a prolonged loud noise and a sky filled with a fiery glow made by a meteorite with a long reddish tail that streaked through the sky before striking the earth near the small community of Finch (Greene County), four miles southwest of Paragould. Two major fragments were found and displayed in Paragould for several weeks. The first discovered was small but weighed about seventy-five pounds—unusually heavy for its size. The second fragment was found thirty days later. Buried nine feet into hard clay two and a half miles from where the first rock was found, the “big rock” measured twenty-four inches in height, twenty-eight inches in length, and twenty-four inches in breadth. It weighed 820 pounds, and five men and a team of horses spent three hours dislodging it. The larger rock is on display at the University of Arkansas.

In 1936, while Frank Reynolds and his brother-in-law, Lowell Rodgers, were fishing in Hurricane Creek just north of Paragould, Reynolds hit something that gave off a “metallic sound.” Curious, the two men pulled out of the deep sand in the creek bed an enormous thigh bone, three and a half feet in length. They worked almost continuously during the next twenty days removing all bones from the creek. The two men toured the state in a borrowed truck for three weeks, charging ten cents a look. When the two got to Fayetteville (Washington County), they were told by members of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville science faculty that they had found the skeleton of a 10,000-year-old mastodon. Reynolds was offered $5,000 for the bones by a man from Kentucky, but instead he chose to give them to the museum at Arkansas State University (ASU) in Jonesboro, not far from his home north of Paragould.

World War II through the Modern Era

When the call went out for men between eighteen and forty-five to register for selective service for World War II, 7,182 men from Greene County responded. A total of 2,344 men in the county went into military service, including 395 volunteers. The Adams Jackson Post of the American Legion assumed the responsibility of inscribing the seventy-eight names of those killed in the war to a new wing that was added to the Statue of Liberty memorial monument on Court Square. (Two names were added to the monument as casualties of the Korean War, along with twelve names of men who died in Vietnam and two killed in the Persian Gulf War.)

Construction of a new hospital began in 1941 on land given by Joseph R. Bertig to a nonprofit corporation, which had sponsored a subscription drive to raise funds to be added to a secured Works Progress Administration (WPA) grant. The hospital was three-fourths completed when WPA funds were depleted and the agency was abolished in 1943. Funds were obtained to complete the construction after the war. The new hospital was completed on September 25, 1948, and dedicated on October 16, 1949. In 2005, the name was changed to the Arkansas Methodist Medical Center, and numerous expansions and additions have been made. The hospital provides services for a number of counties in northeast Arkansas and southeast Missouri, and is one of Paragould’s largest employers.

Paragould has two radio stations; KDRS-KLQZ and KDXY-FM. The award-winning Paragould Daily Press publishes six days a week (including Sundays).

Industry

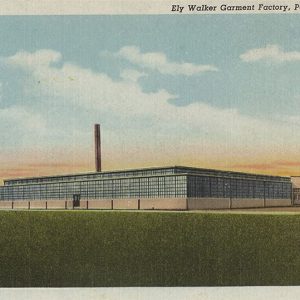

Although the Missouri Pacific opened a “round house” locomotive repair shop in Paragould in 1911 (and eventually employed nearly 300 men), it was the middle of the Depression years before local civic leaders made an organized effort to attract large industry. The Ely-Walker Shirt Factory opened in 1937 and employed nearly 300 people. During World War II, the company completed nineteen contracts supplying the army and navy with shirts.

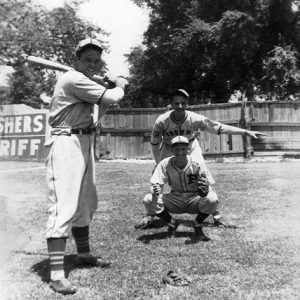

Ely-Walker located in Paragould mainly because of the efforts of Belle Hodges Wall, secretary of the Paragould Chamber of Commerce. Wall also played an important role in securing Crowley’s Ridge State Park, Harmon Playfield, and a minor league (class D) baseball team.

Following World War II, Paragould city officials and the Chamber of Commerce began a successful effort in attracting large industries. First to open was the Ed White Shoe Factory (1947), and then Wonder State Manufacturing (1950). Foremost Foods’ Dairy Division built a large plant in Paragould in 1952 and expanded several times.

The first big national plant to open in Paragould was Emerson Electric Company of St. Louis (1955). Manufacturing electric motors for laundry appliances, the company became Paragould’s largest employer, employing over 1,500 people. At one time, the plant produced more fractional electric motors than any other plant in the United States. With the location of Emerson in Paragould, the city received a boost that propelled the town through several decades of steady industrial growth.

Among the reasons for modern-day industrial growth is Paragould’s low industrial property tax rate ($8 per $1,000 of market value); the availability of skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled workers; extremely competitive utility rates (electrical rates among the lowest in the nation); strategic location in the proximity of the St. Louis and Memphis Railroad; a 700-acre industrial park adjacent to the Union Pacific main line railroad; competitive state and local incentive packages; excellent schools; and many available service-related facilities.

Education

A one-room subscription school was opened in Paragould in 1883 by Professor Hopkins from Gainesville. Seven years later, Professor R. S. Thompson opened the Thompson Classical Institute, which included an elementary school as well as a course of study equivalent to a four-year high school. Tuition was fourteen dollars a term.

The West Side School was the first public school in the city. Used for all grades, its first high school graduation class in 1903 consisted of four young women who had completed ten grades of study. The eleventh and twelfth grades were added by 1907. A new high school was built on the Westside property in 1909, leaving the old building to be used solely for elementary grades.

In 1909, the Arkansas legislature provided for the establishment of four agricultural colleges to be located in four state districts. Greene County was included in the First District. A board was appointed to campaign for the location of one of the schools in Paragould. A site was selected beyond Linwood Cemetery and offered by the town as an inducement to attract the school. However, businesspeople in Jonesboro offered more, $31,000 and 200 acres. Several citizens worked hard to raise funds to outbid Jonesboro but failed because many believed a large school of non-residents would disturb the town’s peaceful atmosphere. The college is now Arkansas State University in Jonesboro.

The Paragould School District is a consolidated structure comprising the former school districts of Oak Grove, Stanford, and Paragould. Over 2,800 students are enrolled in four elementary schools (K–4), one middle school (5–6), one junior high school (7–8), and one high school (9–12).

The Greene County Technical School District encompasses the southern half of Greene County as well as portions of Paragould and Craighead County. Grades K–12 provide educational programs for over 2,800 students. A preschool/daycare center is also on campus. An extensive vocational-agriculture program provides educational experiences for work in industry and agriculture.

Paragould is home to Crowley’s Ridge College, a private, church-affiliated, two-year college. The Black River Technical College/Greene County Industrial Training Center offers courses in a variety of different programs. Arkansas Northeastern College for some years operated a center located on the Arkansas Methodist Medical Center campus and primarily offered courses related to health and administrative services. From 2001 to 2019, Arkansas State University at Paragould, a branch campus of ASU in Jonesboro, offered general educational courses in practically every educational department as well as a few upper-level courses.

Famous Residents

Adolph Bertig, a Jewish immigrant, was known as the Merchant Prince of Paragould. Several Paragould residents have become nationally prominent: George T. F. Johnson, U.S. Navy Medal of Honor recipient in the Civil War; Marion Futrell, governor of Arkansas from 1932 to 1936 (whose house was converted into the Greene County Museum); Frank Nash, a famous bank robber from a prominent Paragould family, who was killed in the “Kansas City Massacre”; Irwin Wolf, president of Kaufman’s Department Store in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Bill Justice (a.k.a. Richard Travis), a Hollywood actor; Jeanne Laverne Carmen, a B-movie actress and trick shot golfer; Marlin Stuart, a major league pitcher; Bill Miles, a navy rear admiral; Lee Purcell, a Hollywood actress; Paul Douglas, an air force brigadier general; and Edward Partain, a lieutenant general and Fifth Army commander. Paragould is also the birthplace of singer/songwriter Iris DeMent and longtime U.S. Department of Justice lawyer Stephen Samuels, known nationally as “Mr. Clean Water Act” for his expertise on environmental law.

For additional information:

Crowley, Benjamin H. The History of Greene County. Paragould, AR: B. H. Crowley, 1906.

Diaries of John Vincent Landrum, July 20 to December 31, 1890. Greene County Historical and Genealogical Society Archives, Paragould, Arkansas.

Hansbrough, Vivian. History of Greene County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Democrat Printing and Lithographing Co., 1946.

Lancaster, Guy. “‘Negroes Are Leaving Paragould by Hundreds’: Racial Cleansing in a Northeast Arkansas Railroad Town.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 41 (April 2010): 3–15.

Mueller, Myrl Rhine. A History of Greene County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Parkhurst Book Design, 1984.

Mack Hamblen

Greene County Historical and Genealogical Society

Arkansas Department of Workforce Services (ADWS)

Arkansas Department of Workforce Services (ADWS)  Bertig Bros.

Bertig Bros.  Collins Theatre

Collins Theatre  Corner Cafe

Corner Cafe  Eight Mile Creek Bridge

Eight Mile Creek Bridge  First Baptist Church

First Baptist Church  Garment Factory

Garment Factory  Greene County Museum

Greene County Museum  Greene County Courthouse (1888)

Greene County Courthouse (1888)  Greene County Courthouse (1888)

Greene County Courthouse (1888)  Greene County Map

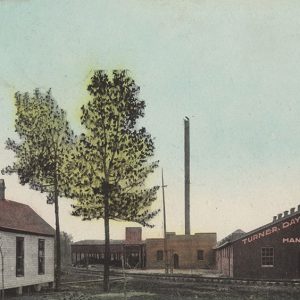

Greene County Map  Handle Factory

Handle Factory  "Mama's Opry," Performed by Iris DeMent

"Mama's Opry," Performed by Iris DeMent  Paragould Band

Paragould Band  Paragould Browns

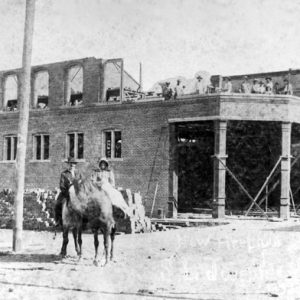

Paragould Browns  Paragould Building Construction

Paragould Building Construction  Paragould Cotton

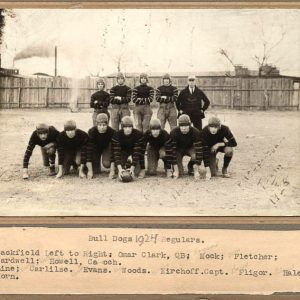

Paragould Cotton  Paragould Football Team

Paragould Football Team  Paragould Meteorite

Paragould Meteorite  Paragould Recruits

Paragould Recruits  Paragould Sanitarium

Paragould Sanitarium  Paragould Soliphone

Paragould Soliphone  Paragould Stave Mill

Paragould Stave Mill  Paragould Street Scene

Paragould Street Scene  Paragould Street Scene

Paragould Street Scene  Paragould Street Scene

Paragould Street Scene  Paragould Trust

Paragould Trust  Paragould Utilities

Paragould Utilities  Security Bank

Security Bank

I would like to make a comment about the Haileys that lived in the area of Miller community and Coffman community in Greene County. The name is recorded as Haley but should be Hailey. My grandfather was Zack Beasley Hailey. My dad was Zack Edward Hailey. He married Dewanda Ross Wilkerson, the great-granddaughter of Ross Coffman. My grandmother was Mary Wadley (Wilkerson), the granddaughter of Ross Coffman.