calsfoundation@cals.org

Paragould Race Riots

Paragould (Greene County), which incorporated in 1883, experienced a series of incidents of racial violence and intimidation from 1888 to 1908. (In this context, a race riot is defined as any prolonged form of mob-related civil disorder in which race plays a key role.) The outmigration of African Americans that followed these various incidents helped to cement its reputation as a “sundown town.”

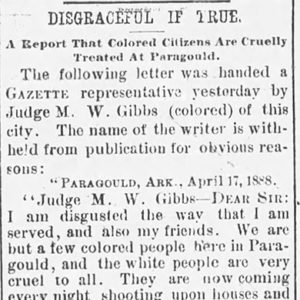

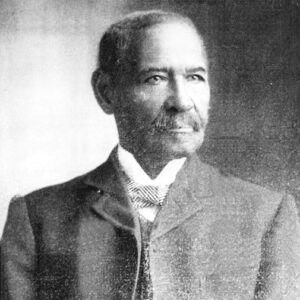

On April 21, 1888, the Arkansas Gazette published a letter sent by a member of the black community and addressed to the country’s first elected African-American municipal judge, Mifflin Wistar Gibbs. The writer sought Gibbs’s help, telling him that “I am disgusted the way I am served, and also my friends. We are but a few colored people here in Paragould, and the white people are very cruel to all. They are now coming every night shooting upon houses and throwing rocks upon our houses every night.” According to the writer, Paragould’s black citizens had land, but “we cannot stay upon it to save our lives. They burn our houses down and church down, and…we can’t have no peace here.” On April 27, the paper published another letter, this time from a white citizen of Paragould. He reported that “the colored people have a right to complain at the treatment they have received, and the statement which you publish, though somewhat exaggerated, is in the main about correct.” No information exists as to whether or not local authorities followed up on this.

Trouble arose again in October 1892. According to the Gazette, as a result of the murder of a man named Monroe Pulley, “twenty-five or thirty men went to the houses and residences of most of the colored population” of Paragould “and notified them to leave within three days and nights.” According to the report, a number of African Americans had already left, or were preparing to, although “leading citizens are opposing this and doing all in their power to quiet the negroes, as there is a lot of them here who are perfectly harmless, also industrious and attend to their own affairs and are owners of property in their own right.” No information was provided by the newspaper about the circumstances of Pulley’s murder or why African Americans were targeted in this affair.

Seven years later, on August 3, 1899, a self-appointed vigilance committee went around to all the African Americans in Paragould and told them “to leave the city of Paragould, bag and baggage, on or before next Saturday night, and never return again, for any purpose whatsoever, or suffer the consequences of staying.” Although the Gazette identified the committee’s members as “the lowest elements” of the town, and the mayor decried their actions, when black residents asked for the mayor’s protection, he refused to provide it. By the following day, the Gazette reported, African Americans began to leave for other parts of the state: “None of them had been killed and none were shot at, but they were alarmed for their safety.” Throughout the weekend, “cabins where the remaining negroes reside were stoned,” as was the Stancill Hotel, for reasons not specified. Five days later, the Gazette reported that there were fewer than twenty-five African Americans left in the town.

This particular incident was apparently a result of labor problems. The factories in town had been importing black workers, and as these employees worked for less pay than area whites, this caused resentment. According to the Gazette, on August 5, “many of the best citizens of town” held a meeting at the county courthouse, where they passed three resolutions concerning “the residence of the negro in Paragould, and the importation of negro labor for any purpose whatsoever.” The first of these resolutions consisted of a rebuke aimed at the members of the vigilance committee, saying that their actions were “calculated to retard and hinder the growth and best interests of the town and surrounding community.” The second urged that “the colored residents of Paragould be afforded ample protection of person and property.” The third hinted at the existence of a labor problem, and asked the lumber mills and other industries to cease hiring “negro labor for any purpose whatever at this time” and implored “the lumber companies or the corporations in our midst employing labor to refrain from giving employment to any others than those who are residents of our community.”

These events received national coverage. The Houston Post reported on August 7, 1899, that there were around 500 African Americans in Paragould at the time, which was an exaggeration (the 1880 census recorded only seventy-five black residents of the entire county, and this number grew to only 161 in 1890). The Post listed two basic causes for the unrest. The first was that white sawmill workers in the area had gone on strike, and the owners had threatened to bring in black workers to break the strike. The second cause listed was that “the town was overrun with worthless, indolent negroes and that petty crime had become such a nuisance that the citizens decided to run the negroes out.” The Post also asserted that members of the vigilance committee ignored the criticisms expressed at the town meeting and began running blacks out of town: “Some negroes were taken to the woods and severely flogged and warned not to come back.” Reports indicated that some whites had apparently come to the defense of those who worked for them as cooks and servants, and “announced their intention of protecting their servants with their lives if necessary.”

The Baxter Springs News of Kansas reported on August 12, 1899, that Paragould originally had around 150 black residents, but that following these events, the population had been reduced to twelve. According to the News, “Sentiment in regard to the negro questions is divided, many arguing that, once allowed to gain a foothold here, it will be impossible to control the negroes.”

According to the Census Bureau, by 1900, Paragould had only sixty-eight black residents in a total population of 3,324. There was, however, continued unrest. In April 1902, citizens threw brickbats and rocks through the windows of Paragould’s black Methodist church during a service, causing churchgoers to flee.

A month later, local law enforcement posted a proclamation in the local newspaper, the Daily Soliphone, stating that it would “protect all colored citizens as well as whites in the enjoyment of their liberty,” in response to “certain lawless persons, unknown to us, [who] are sending incendiary messages to the colored citizens of Paragould and ordering them to leave the town, and that by threats of bodily harm.”

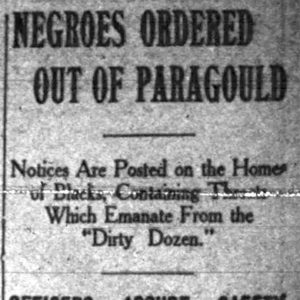

On May 23, the St. Louis Republic reported that Arkansas governor Jeff Davis had forbidden the commander of the state military company at Paragould “to use the militia force at that place in connection with existing racial troubles in Greene County, unless he gives positive instructions.” There were more labor troubles in October 1903, when the Paragould Cotton compress was torched by unknown arsonists. The company’s owners asserted that this happened because they employed African Americans, and they announced plans to rebuild the compress in Forrest City (St. Francis County). On April 9, 1908, the Arkansas Gazette, reported that a group of nightriders who called themselves the “Dirty Dozen” had attacked the homes of Paragould’s remaining African Americans, a population numbering no more than forty, and ordered them to leave town on pain of death.

The black population in Paragould continued to shrink. According to the Census Bureau, there were twenty-eight African Americans living in town in 1920, and only twenty (out of a total population of 5,966) in 1930. In 2010, Paragould had a black population of less than one percent.

For additional information:

“Attacked a Church.” Daily Soliphone, April 14, 1902, p. 1.

“Disgraceful If True.” Arkansas Gazette, April 21, 1888, p. 4.

“Negroes Are Leaving Paragould by Hundreds.” Arkansas Gazette, August 8, 1899, p. 1.

“Negroes Ordered out of Paragould.” Arkansas Gazette, April 9, 1908, p. 1.

“Ordered to Leave the County.” Arkansas Gazette, November 1, 1892, p. 3.

“Paragould Has Lost Cotton Compress.” Arkansas Gazette, October 21, 1903, p. 10.

“The Paragould Outrage.” Arkansas Gazette, April 27, 1888, p. 3.

“Paragould Whitecappers.” Arkansas Gazette, August 9, 1889, p. 4.

“Race War in Paragould.” Baxter Springs News (Baxter Springs, Kansas), August 12, 1899, p. 2.

“A Serious Race Riot.” Houston Daily Post, August 7, 1899, p. 3.

“Troops Not to Interfere.” St. Louis Republic, May 23, 1902, p. 2.

Nancy Snell Griffith

Clinton, South Carolina

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Crowley's Ridge

Crowley's Ridge Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Labor Movement

Labor Movement Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Compress Loss

Compress Loss  Gibbs Letter

Gibbs Letter  Mifflin Gibbs

Mifflin Gibbs  Racial Strife Article

Racial Strife Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.