calsfoundation@cals.org

Oil Industry

The oil industry in Arkansas, which includes exploration and the production, refinement, and distribution of petroleum-based products, exploded onto the state’s economic scene in the early 1920s, and once-local production expanded into an international business. From 1920 to 2003, more than 1.8 billion barrels of oil were produced in Arkansas.

Ten counties in Arkansas produce oil, all in the southern region of the state: Ashley, Bradley, Calhoun, Columbia, Hempstead, Lafayette, Miller, Nevada, Ouachita, and Union. Historically, most of this production has been in Union, Lafayette, Columbia, and Ouachita counties. These four counties have been responsible for more than eighty-five percent of the oil produced in the state.

Evidence of oil in the state existed well before the oil boom of the 1920s. William Brown’s Union Coal Company reportedly built a crude oil refinery east of El Dorado (Union County) to distill oil from lignite coal in 1860. Similar techniques were used to produce modest amounts of oil from lignite at a coal mine near Camden (Ouachita County) in the 1860s. These efforts were limited, however, and ceased some years later from lack of significant profits. Henry E. Kelley’s exploratory well in 1889 in Scott County did not yield enough oil or natural gas to sell commercially but encouraged other exploratory efforts in the northwestern region of the state in the 1890s.

Geologic patterns in southern Arkansas led entrepreneurs at the beginning of the twentieth century to believe that the region held a potential wealth of petroleum and natural gas, as there are certain markers within rocks that indicate the possible presence of oil. In 1914, oil explorers dug an unsuccessful test hole at Urbana (Union County), east of El Dorado. A 1916 effort near the Union-Columbia county line also proved unsuccessful. Samuel S. Hunter commissioned a well some two miles east of Stephens in Ouachita County in April 1920. This well, the Hunter No. 1 well, produced some oil but never enough to sell commercially. This site was later acquired by Standard Oil Company for exploration.

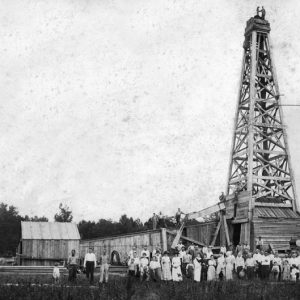

Less than one week after modest finds of oil at the Hunter No. 1 well, the Constantin Oil and Refining Company’s Hill No. 1 well uncovered a deposit of oil and natural gas. The historic south Arkansas oil boom began on January 10, 1921, with the completion of the Busey No. 1 well. Dr. Samuel T. Busey, a globetrotting physician and oil speculator, completed the drilling, one mile southwest of El Dorado, that produced a gusher well that sprayed between 3,000 and 10,000 barrels of oil up to a mile away. The “discovery well” touched off a wave of speculators into the area seeking fame and fortune from oil. The state legislature immediately sent an exploratory train from Little Rock (Pulaski County) for the legislators to inspect the find.

Oil production increased exponentially in a matter of months. In March 1921, Arkansas produced 38,000 barrels of oil to sell on the open market, which increased to 325,000 barrels by April, to 578,000 barrels by May, and to 908,000 barrels by June. By 1922, 900 wells were in operation in the state.

Although Arkansas production ranked far behind such oil-producing states as Texas, Oklahoma, California, and Louisiana, El Dorado immediately became the epicenter of the oil boom. It changed from an isolated agricultural city of approximately 4,000 residents to the oil capital of Arkansas. Twenty-two trains each day ran in and out of El Dorado to Little Rock and Shreveport, Louisiana, and regular air service from Shreveport transported workers and investors.

By 1923, El Dorado boasted fifty-nine oil companies, thirteen oil operators, and twenty-two oil production companies. The city was flooded with so many people that no bed space was available for them, leading to the building of neighborhoods of tents and hastily constructed shacks throughout the city. The city’s population reached a high of 30,000 in 1925 before dropping as the boom played out in the late 1920s.

In 1922, the Smackover Pool was discovered near the Union-Ouachita County Line outside the farming town of Smackover (Union County). Smackover, like El Dorado, also swelled with oil workers and fortune seekers. Its population surged to 25,000 within a few months in 1922 from a mere 131. The oil-producing area of the Smackover Pool covered more than 25,000 acres and, by 1925, had become the largest-producing oil site in the world. The Smackover Pool would eventually produce 583 million barrels of oil by 2001.

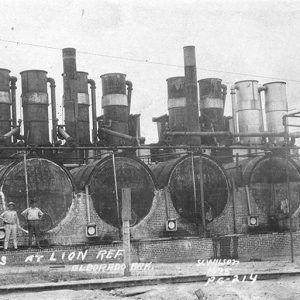

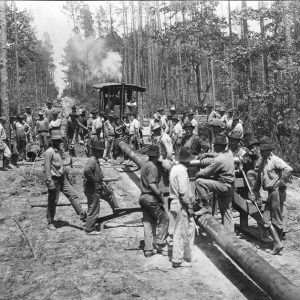

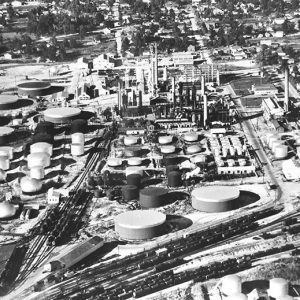

An oil refinery had been completed some years earlier at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to serve producers in Oklahoma. The oil boom prompted the Arkansas Refinery Company to build a refinery at Picron, near Little Rock, which began processing in May 1921. South Arkansas producers also constructed local refineries. By August 1921, five refineries operated in Union County. This included the refinery built by the new Lion Oil Company, organized by businessmen in the El Dorado area. In 1937, the company bought the original site of the first village in Union County, Champagnolle, to build a loading ramp, storage tank, and pipeline from its refinery to the small port on the Ouachita River. Murphy Oil, headquartered in El Dorado, began as a holding company for lumber and banking interests in south Arkansas at the beginning of the twentieth century, typical of the leading economic interests of the region at the time. By the 1930s, oil and natural gas had become the most important aspects of Murphy Oil’s operations.

At the peak of the boom in 1925, some 3,483 wells produced seventy-three million barrels of oil in one year. So much oil was produced that trains could not transport all the oil out of the area to refineries. In 1926, Smackover producers began storing oil in open earthen pits, causing much of this oil to be lost due to contamination from rain and spills. It also contaminated the groundwater itself. Many pools proved to have relatively limited supplies. In the early 1920s, wells often ran at full capacity, which let many of the wells run dry within five years of the boom. The Arkansas Conservation Commission issued recommendations to producers to prevent such waste, and, with several larger oil companies, filed lawsuits in the late 1920s to extend the life and productive efficiency of the oil fields.

The state established the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission in 1939 to regulate the state’s oil and natural gas industry. The commission regularly holds hearings and issues permits for natural gas and oil exploration and well development. Originally a seven-member commission, the state legislature expanded it to nine members in 1985. The commission lists among its duties the prevention of waste; the encouragement of conservation of oil, natural gas, and brine (salt water produced with crude oil, often containing bromine); and the protection of the property rights of producers. Since 1939, the commission has issued 38,000 permits to drill oil, gas, and brine wells. The commission currently has offices El Dorado, Fort Smith, and Little Rock.

The boom came to an end by the late 1920s, but the industry nevertheless continues its presence in the region. Oil production dropped dramatically, from a little over fifty-eight million barrels in 1926 to twelve million barrels by 1932. An additional twelve major pools were discovered between 1936 and 1947. These included the Shuler and Magnolia pools, discovered in Union County in 1937 and Columbia County in 1938, respectively. These fields have each produced more than 110 million barrels of oil. From the late 1930s into the late 1960s, the oil industry enjoyed a resurgence in south Arkansas, though paling in comparison to the boom years of the early 1920s. Production between 1939 and 1967 stayed above twenty million barrels of oil each year, rising slightly during World War II as levels hit thirty million barrels annually for 1944 and 1945, with levels staying near that mark until 1961. One last major pool, Chalybeat Springs, was discovered in 1971. By 1999, production had dropped to seven million barrels but rose slightly to 7.3 million barrels in 2000. Lion Oil became part of Ergon, Inc., in 1985 but continued its refining operations in El Dorado. In 1996, Murphy Oil Corporation expanded into retail gasoline sales. Murphy USA gas stations operate in twenty-one states, primarily in parking lots of Walmart Inc. retail stores, another Arkansas-based corporation.

Although oil production by the early twenty-first century slowed considerably from the boom period of the 1920s, oil still has a strong economic and cultural influence on the region. Some communities, such as Standard-Umpstead (in Ouachita County), were initially founded to support the oil industry. The Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources, located just outside Smackover, was established to commemorate the oil boom and its impact on the area. El Dorado calls itself “Arkansas’s Original Boomtown.” In 2000, the annual value of the state’s total mining production (from minerals, oil, and natural gas) topped $1 billion. Oil companies still rank among the leading employers in south Arkansas.

For additional information:

Buckalew, A. R., and R. B. Buckalew. “The Discovery of Oil in South Arkansas, 1920–1924.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Autumn 1974): 195–234.

Cordell, Anna H. “Champagnolle: A Pioneer River Town.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Winter 1957): 37–45.

Ladwig, Kelli C. “Pope Goes the Weasel: How Greed and a Good Barbecue Hoodwinked a Small Town.” Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal 22.2 (2023). https://scholarworks.uark.edu/inquiry/vol22/iss2/6/ (accessed January 29, 2024).

Moneyhon, Carl H. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Parker, J. Scott. “A Changing Landscape: Environmental Conditions and Consequences of the 1920s Union County Oil Booms.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 40 (Spring 2001): 31–52.

Ragsdale, John G. “Oil Development in South Arkansas, 1921–2001.” South Arkansas Historical Journal 3 (Fall 2003): 18–24.

Spencer, Annie Laurie. “Arkansas’ First Oil Refinery.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Winter 1957): 335–341.

Kenneth Bridges

South Arkansas Community College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.