calsfoundation@cals.org

Lead and Zinc Mining

The history of lead and zinc mining in Arkansas is linked because ores of these two metals often occur together. Lead and zinc in Arkansas occur principally along the upper White River and its tributaries in Baxter, Boone, Independence, Lawrence, Marion, Newton, Searcy, Sharp, and Stone counties. Other locations include the Kellogg Mine in Pulaski County and the Ouachita Mountain mineral belt.

Lead (Pb) is a soft, highly dense metal recognized for its low melting point and superb resistance to corrosion. Galena (PbS), containing about eighty-six percent lead, is the only lead mineral of commercial importance in Arkansas. Silver is sometimes found as an impurity that, in larger concentrations, can be extracted as a byproduct. Lead was once used to manufacture paint and pigments, lead pipes, bullets and shot, glassware and ceramics, and roof cladding. Today, most lead is used to manufacture car batteries.

Like lead, zinc (Zn) is a malleable, corrosion-resistant metal. Sphalerite (zinc sulfide, containing sixty-seven percent zinc) and smithsonite (zinc carbonate, containing forty-eight percent zinc) were the two most commonly mined zinc ores in Arkansas. Historically, zinc was used as an alloy to make brass, rolled into sheets for roof cladding, melted for “hot dip” and other galvanizing, and pulverized for paints. Today, zinc is also used for batteries.

Beginning in 1807, the U.S. government reserved federal lands with mines and salt springs to be leased. Missouri’s notorious John Smith T filed the earliest lead mine claims on the White River in 1807–1814. The Shawnee apparently carried out the earliest lead mining in Arkansas on the White River, as indicated by an 1814 application on behalf of Colonel Lewis (Chief Quatawapea), the tribe having earlier been granted the right to mine lead in Missouri. Geologist Henry R. Schoolcraft’s published accounts of his 1818–1819 reconnaissance of the Ozarks first called America’s attention to lead resources in the Ozarks. Arkansas’s lead deposits lay practically undeveloped in 1846 when the U.S. Congress authorized the sale of federal mineral lands in Arkansas.

Early lead producers had to either smelt galena in wasteful log furnaces or transport it overland to Missouri’s hearth furnaces, the cost of transportation typically taking all the profit. This was not the case, however, with Arkansas’s only significant argentiferous (silver bearing) lead mine. Its silver content made ore from the Kellogg Mine north of Little Rock (Pulaski County) economical to ship long distances to refineries able to extract its silver. Some 300 tons of silver-lead ore raised in 1848–1849 were refined in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; and Wales. The Kellogg Mine included Arkansas’s deepest mine shaft (1,125 feet deep) by 1940 when mining there ceased.

The Arkansas legislature in 1857 authorized a geological survey of the state. Newly appointed state geologist David Dale Owen conducted a reconnaissance of northern Arkansas in 1857–1858, which located numerous indications of lead and zinc. Owen found that the Independence Mining Company of St. Louis, Missouri, was mining smithsonite for zinc ore at modern Calamine (Sharp County), making Calamine one of America’s early zinc mines. The company suspended operations during the Civil War.

At the outbreak of the war, Confederate troops seized the rich Granby lead mines of southwest Missouri, then touted as able to provide all the lead needed for the Confederate cause. In 1861, 75,000 pounds of pig lead a month were being hauled overland to Van Buren (Crawford County), to be shipped to the Memphis, Tennessee, ordnance works. The loss of Missouri to the Union following the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas effectively meant losing this important war materiel source. The Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau mined lead and saltpeter (an ingredient in gunpowder) in Newton, Marion, Pulaski, and Sevier counties. However, these operations proved too close to enemy lines and were soon abandoned for more secure sources in Texas.

Under Reconstruction, the development of Arkansas’s lead and zinc resources rebounded but faltered. The American Zinc Company renewed mining at Calamine in 1871 but soon closed. In 1882, the Carthage and Arkansas Mining Company erected a smelter and platted the town of Boxley (Newton County). The company shipped five car loads of lead from Eureka Springs (Carroll County), the nearest railroad point, to St. Louis, but the ninety-five-mile wagon haul made mining cost prohibitive.

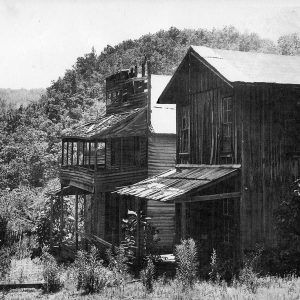

The Morning Star Mine in Marion County, discovered on Rush Creek in 1880, provided a bonanza of remarkably pure zinc. Andy George, one of the mine’s discoverers, later recalled that mineral “flickers,” picked up by Allen Sutzer’s girls while searching for the family’s cows, had first tipped him off. Thinking it was silver, he and John Wolfer constructed a furnace. Instead of melting, the heated ore unexpectedly evaporated in rainbow-colored fumes, which indicated zinc. Within a few years, the Morning Star Mine produced a huge zinc carbonate boulder weighing 12,750 pounds and appropriately nicknamed “Jumbo.” When exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, Jumbo won the highest awards.

Although demand for zinc was then limited, this changed quickly in the late 1890s. Germany’s Silesian mines, then Europe’s major zinc provider, dwindled. New uses multiplied, and American zinc exports surged.

The future of Arkansas zinc mining seemed bright—if only American industry would invest. In the late 1800s, St. Louis and Chicago, Illinois, competed for the crown of America’s next great city. Each were growing manufacturing giants with large appetites for raw materials. While both cities benefited from America’s vast agricultural heartland, the Ozark Mountains, with relatively low agricultural prospects, occupied St. Louis’s entire southwest quadrant. But the Ozarks had proven resources in base minerals, stone, and timber.

This was an age when newspapers, then the most prevalent medium of mass communications, actively collaborated with industrial barons and politicians to promote economic progress. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat in 1887 sent a reporter to explore the Ozarks with special reference to mining. Including subsequent tours in 1895, 1897, and 1899, the Globe-Democrat published more than 200 feature articles on the theme of development opportunities in the Ozarks. Most were written by Walter B. Stevens, one of America’s greatest newspaper reporters and later secretary of the St. Louis World’s Fair. Stevens wrote several articles from Arkansas’s northern mineral district. The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) in 1900 reprinted and distributed a collection of these articles in a publication called The Ozark Uplift.

For John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company, Arkansas’s northern lead and zinc district represented an opportunity to challenge a growing national monopoly in zinc. Convinced that smelter owners had been conspiring to pay the lowest possible prices for their ores, miners in 1898 formed the Missouri-Kansas Zinc Miners Association. By adhering to production limits, their members temporarily doubled prices. Many of America’s industrial-scale smelters were then located near coal and natural gas sources in eastern Kansas and Oklahoma. In January 1899, Standard Oil—through a subsidiary—purchased ten coal- and gas-fired zinc smelters in Kansas. Within a few months, Standard Oil’s newly acquired smelters announced plans to finance and develop the largely inaccessible zinc fields of Marion County, Arkansas. That August, the Kansas City Star published an effusive feature story on lead and zinc mining opportunities around Yellville (Marion County). Plans to extend railroads quickly followed. With a new geological survey in hand, the Santa Fe and Frisco railroads quietly purchased more than 15,000 acres of zinc land near Yellville in December 1899; they then announced plans to extend a railroad from the nearest point, Eureka Springs. Northern Arkansas was being touted as the “richest lead and zinc mining district in the world.”

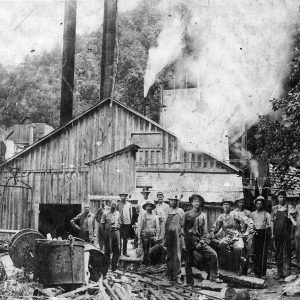

The first rail car of zinc ore, from the Almy Mine, was loaded at Harrison (Boone County) in the fall of 1901 and shipped over the St. Louis and Northern Arkansas Railroad to a smelter in Cherryvale, Kansas. In 1905, northern Arkansas cheered the completion of the White River Railway from Batesville (Independence County) to Carthage, Missouri.

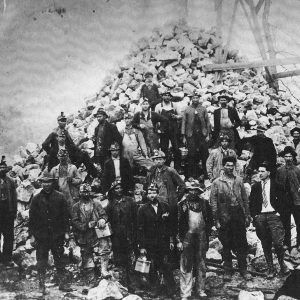

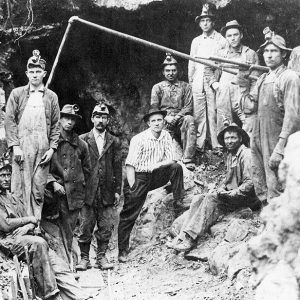

Unlike with some other mineral resources, lead and zinc mining could be carried out by individuals on a small-scale basis in addition to the large-scale operations financed by industrial barons. Arkansas farmers supplementing their incomes could mine lead and zinc off season. Prospectors followed a hypothesis that a zone of fissures called the “Ten O’Clock Run” extended from Missouri to beyond the Buffalo River in Arkansas in a northwest-southeast orientation. Prospectors and miners shared a colorful vocabulary, for instance calling sphalerite “black jack” or “jack” and smithsonite “turkey fat” or “dry bone.”

World War I fueled an explosive rise in demand for both lead and zinc, aided by federal price supports. Among other uses, zinc was an alloy in brass shell casings, and sheet zinc was specified to line munitions boxes for protection from corrosive salt air. During the pre-war period of 1908–1914, the annual output of Arkansas zinc mines had fluctuated between 474 and 994 short tons of concentrates. However, in 1916 alone, Arkansas produced 6,815 short tons of zinc concentrates (from 203,600 short tons of crude ore sold or treated). Arkansas in wartime annually produced five to six percent of U.S. zinc ores. Arkansas’s lead production likewise peaked in 1916–1917 with 813 short tons of galena ore netting $76,000 total for the state’s lead producers. Arkansas was also then home to three of America’s fifty-one zinc smelters, one in Van Buren and two in Fort Smith (Sebastian County). These smelters burned natural gas from the Arkansas River Valley gas fields. The companies also contracted with the municipalities of Van Buren and Fort Smith to provide them with natural gas.

Despite years of extravagant exaggeration on the part of boosters, who steadfastly asserted that a lack of railroads and good roads prevented lead and zinc development, in truth Arkansas was no more isolated, nor its terrain more rugged, nor its access to railroads worse than the nation’s major lead-producing states of Missouri, Idaho, Colorado, and Utah. A difference, however, was that the Rocky Mountain deposits were typically argentiferous, making mining cost effective, and Missouri’s deposits, although containing minimal silver, were massive. Arkansas’s lead and zinc deposits were simply too limited and irregular to warrant significant industrial and infrastructure investments, and once the railroads finally extended through north Arkansas, companies experienced a series of bankruptcies and bailouts.

Although lead mining ceased statewide by 1959, geologists now believe significant potential exists in north Arkansas for the discovery of deep (more than 1,500 feet) deposits of lead and zinc as the southern extension of the New Viburnum lead district in southern Missouri.

The cultural legacy of lead and zinc mining includes place names such as the towns of Calamine, Galena (Howard County), Lead Hill (Boone County), and Zinc (Boone County). Arkansas folklore includes more than a dozen legends about lost lead mines, including the Lost Fitzwater & Stout Lead Mine in Baxter County, the Old John Cross Lead Mine in Newton County, and the Lost Lott Lead Mine in Sharp County. Such legends provided the backdrop for a historical novel, The Lead-Hunters of the Ozarks (1927).

For additional information:

Branner, John C. Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Arkansas for 1892. Vol. 5, The Zinc and Lead Region of North Arkansas. Little Rock: Thompson Lith. and Ptg. Co., 1900.

Ferguson, Jim G. Outlines of Arkansas Geology. Little Rock: State Bureau of Mines, Manufactures, and Agriculture, 1920.

Johnston, James J. “Bullets for Johnny Reb: Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Summer 1990): 124–167.

Owen, David Dale. First Report of a Geological Reconnaissance of the Northern Counties of Arkansas, Made during the Years 1857 and 1858. Little Rock: Johnson & Yerkes, State Printers, 1858.

Pitcaithley, Dwight. “Zinc and Lead Mining along the Buffalo River.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Winter 1978): 293–305.

Schoolcraft, Henry Rowe. Journal of a Tour into the Interior of Missouri and Arkansaw. London: Sir Richard Phillips and Co., 1821.

Stevens, Walter B. “The Ozark Uplift. Faults and Their Relation to North Arkansas Mineral.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 7, 1899, p. 8.

———. “The Ozark Uplift. Its Cracks and Their Relation to the Arkansas Zinc Field.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 2, 1899, p. 6.

———. “The Ozark Uplift. What Mr. Chase Made of the Original Arkansas Proposition.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat. October 6, 1899, p. 6.

U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Resources of the United States, 1917. Part I, Metals. Washington DC.: Government Printing Office, 1921.

Robert A. Myers

Champaign, Illinois

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.