calsfoundation@cals.org

Searcy County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Marshall |

| Established: | December 13, 1838 |

| Parent County: | Marion |

| Population: | 7,828 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 665.83 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

936 |

1,979 |

5,271 |

5,614 |

7,278 |

9,664 |

11,988 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

14,825 |

14,590 |

11,056 |

11,942 |

10,424 |

8,124 |

7,731 |

8,847 |

7,841 |

8,261 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,195 |

7,828 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

7,123 |

91.0% |

| African American |

5 |

0.1% |

| American Indian |

73 |

0.9% |

| Asian |

20 |

0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

5 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

46 |

0.6% |

| Two or More Races |

556 |

7.1% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

140 |

1.8% |

| Population Density |

11.8 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$36,438 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$20,410 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

21.9% |

|

Searcy County is in the Boston Mountains and the Springfield Plateau sections of the Ozark Plateau. Marshall is the county seat and commercial center; Leslie is significant for the Missouri and North Arkansas (M&NA) railroad and timber products; and St. Joe, an old mining center, was also on the railroad and is the first town along Arkansas 65 north of the Buffalo River. Farther northwest is Pindall, an old railroad stop first known as Kilburn Switch, and the old regional commercial center became home to two timber manufacturing companies. Gilbert, another railroad stop, and on the Buffalo River, was originally a point for logs and cotton taken down the river to be placed on the M&NA.

In the early 1920s, a colony of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) from Illinois and other states settled in the Gilbert area. The failure of the M&NA after World War II and the decline of the economy forced their Bible college to move to Joplin, Missouri, and the area to lose population. The 1972 designation of the Buffalo as a national river left Gilbert as the only private property on the river, and it has prospered. The communities of Snowball and Witts Springs were once commercial centers, but improved transportation in the 1950s sent business to Marshall, and Snowball’s school and post office closed in the 1960s. Witts Springs retained its post office and elementary school after consolidating with Marshall in 2004.

European Exploration and Settlement

Northwestern Arkansas was Osage territory from at least the sixteenth century until 1808, when the tribe negotiated a sale to the United States and moved to Indian Territory. But unnamed Native Americans of the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, Hopewell, and Mississippian cultures had left their remains in north-central Arkansas for more than 10,000 years. By the eighteenth century, European diseases and social disruptions had wiped out almost all Native Americans in the area.

European and American administrators knew of this area only from Native American reports because European population was sparse. On June 11, 1793, Don Joseph Valliere, captain of the Sixth Regiment of Louisiana under the Spanish government, received a land grant from Baron de Carondelet, Governor General of the Spanish Province of Louisiana and Florida, extending about twenty miles on each side of the White River to its source beginning at the mouth of the Buffalo and the Big North Fork. But Spanish officials never visited the land, and Valliere did not settle

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The United States obtained title to the land by the Louisiana Purchase. In 1806, John B. Treat of the Arkansas Trading House at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) reported that, according to Indian information, the source of the Buffalo was in the neighborhood of other springs flowing into the Arkansas. There was little, if any, American presence when several thousand acres, including all of future Searcy County, were granted to the Western Cherokee between 1808 and 1817. In addition to the Cherokee came Shawnee and Delaware families, all of whom were in Searcy County.

Although the United States bought the north Arkansas grant of the Western Cherokee in 1828, some Cherokee, Shawnee, and Delaware remained for about seven more years. They introduced selected white families to the area and were noted by settlers as late as 1836. Robert Adams was taken to Bear Creek by Shawnee Peter Cornstalk, according to family tradition, and became the first permanent white settler in Searcy County. Adams was the first cousin of Mary Adams, reported by early settler John Tabor and quoted by Mountain Echo of Yellville (Marion County) editor William R. Jones to have married Cornstalk. Cornstalk is identified by William B. Flippin, early Marion County settler, as a Shawnee, a cousin of Tecumseh, living below the mouth of the Buffalo River on White River. In 1829, when early government surveyors ran a line along the southern boundary of township 14 North, they identified a Shawnee village near where Adams settled.

By 1835, enough people had settled in north-central Arkansas to petition for a separate county. On November 5, 1835, the Arkansas General Assembly established Searcy County from western Izard County. This original Searcy County now comprises Marion, Searcy, and parts of Boone, Baxter, and Stone counties. The county was named for Richard Searcy (1794–1832), prominent civil servant, major landowner, and circuit court judge. In September 1836, the first Searcy County’s name was changed to Marion in honor of Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion, and in 1838, Yellville was established as the regional post office of Marion County.

The southern half of Marion County had been settled fairly heavily. State senator Charles R. Saunders lived on Bear Creek from before 1834. More families arrived from 1835 to 1838, prompting the legislature on December 13, 1838, to create a new Searcy County from the southern part of Marion County. The act made the residence of James Eagan the temporary county seat and provided for election of commissioners to locate a seat of justice. The commissioners chose a place on Bear Creek as the county seat and named it Lebanon; a post office was established there on March 7, 1840. Between 1840 and 1850, post offices were opened in Wiley’s Cove, Locust Grove, and Point Peter.

In the decade before the Civil War, the county seat was moved from Lebanon to its current location (present-day Marshall) on a bench of Devil’s Backbone Mountain and named Burrowville (sometimes spelled Burrowsville) for Napoleon Bonaparte Burrow, a slave-owning secessionist politician. In the year leading to Arkansas’s secession from the United States, Searcy County men joined those of surrounding counties to oppose secession. At the second session of the Arkansas Secession Convention on May 6, 1861, Searcy County’s representative, John Campbell, was one of five who voted against secession, and he was the last of four to allow his vote to be changed to favor it.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Searcy County provided two companies for the Confederacy by October 1861. Unionists formed a secret organization, the Peace Society, to oppose Confederate military service and for mutual support. The Peace Society existed in several counties in north-central Arkansas. More Peace Society members are identified in Searcy County than in any other county. The organization was betrayed on November 17, 1861, in Van Buren County by John Holmes, and the discovery of the society spread rapidly. Investigations of the Peace Society first in Fulton County, then part of Izard County, led to its discovery on the (1861) Izard-Searcy county line. When it was discovered in Searcy County on November 20, Colonel Samuel Leslie called out the Searcy County militia. The militia arrested more than 100 men, and, in early December, marched eighty-seven of them in chains to Little Rock (Pulaski County). Forced into the Confederate army, they were sent to Bowling Green, Kentucky. Another contingent from north of the Buffalo was marched to Little Rock and forced into the same Confederate regiment, the Eighteenth Arkansas Infantry, under Colonel John Sappington Marmaduke. Many more men hid in the woods until they were caught or killed or could make their way to Union lines.

Attrition was high for Peace Society men forced into Confederate service due to disease, desertion, and injuries. When they could, they returned to Searcy County and hid until they could escape to Union lines. Other Confederate companies were raised in Searcy County, most under the threat of conscription. As they could, these men who were forced into Confederate service deserted or were discharged and went to Missouri to join Union regiments or later to Lewisburg (Conway County) to join the Federal Third Arkansas Cavalry. Searcy County Confederates deserted en masse to return home, some to join guerrilla captains but more to join the Union army. Eventually, six Union companies were composed mostly of Searcy County men, and many other Searcy County men served in clusters in other Union companies.

Neither North nor South felt it was worthwhile to occupy and defend the area, even though the Confederates operated a niter mining operation there until early 1864. This left the area open to guerrillas, outlaws, and raids. Emigration of families to the north or to Lewisburg was heavy, and emigration for men was virtually mandatory, because men were either conscripted or killed on sight if suspected of belonging to the other side. Jayhawking and military foraging devastated the county. At least three engagements took place in the county, with actions at Burrowsville and Richland Creek, and during operations against Confederate cavalry on July 4, 1864.

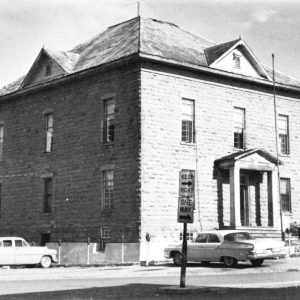

After the war, Union veterans took control of the county, and they and their descendants held Searcy County for the Republican Party even after the end of Reconstruction. By 1870, the county was attracting families from the defeated Southern states. In addition to new homesteads, a lead and zinc mining boom beginning in the mid-1890s brought money and people to St. Joe and north Searcy County. The current courthouse was constructed in 1889 and is included on the National Register of Historic Places.

Early Twentieth Century through the Modern Era

The completion of the St. Louis and North Arkansas railroad to Leslie in 1903 opened the area to agriculture, mining, and timber exporting. Wiley’s Cove Township was the home of several timber factories using white oak to make whiskey barrels, wagon hubs, and other products. After World War I, the price of lead and zinc dropped, the railroad suffered labor problems that closed it for several months, and the Eighteenth Amendment erased the market for whiskey barrels. A decline of the county’s population began.

The war also led to some draft resistance in the county. The Searcy County Draft War led to the death of one man who refused to report for service as well as the arrest of three of his relatives.

The Great Depression stopped new investments in Searcy County, but the national economic situation did not lure many families to leave. The 1930s was a time of stagnation and poverty. Federal assistance programs were adopted with suspicion by some, but Home Demonstration Club projects such as mattress-making and tomato-canning were welcomed, as was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) for young men. The spring 1941 Searcy County Folk Festival on the banks of the Buffalo River, sponsored by the Agricultural Extension Service, was a roaring success. It gained favorable publicity from the Kansas City Star to Little Rock newspapers, with most of the articles written by retired newspaperman Will Rice, who lived near St. Joe. John Paul Rodman, a retired grocer and Presbyterian layman, came to Searcy County about 1937 to spend his last days there but was moved by the plight of the local population to establish Presbyterian churches, with the help of his home church in Corpus Christi, Texas, and to provide economic relief, eventually establishing Rodman’s Chapel and subsidiary missions in Searcy County.

World War II took men away to war. Searcy County’s war casualties began with Webster Paul West, a sailor on board the USS Arizona killed at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Employment in the defense industry at Camden (Ouachita County) and Carlisle (Lonoke County) and in California drew families away from Searcy County, and most eligible men were in military service. No major defense industry appeared in Searcy County, but there were small wood-related contractors.

Concern for the morale of Searcy County servicemen caused William R. Wenrick, publisher of the Marshall Mountain Wave, Searcy County’s only newspaper at the time, not to publish information about the servicemen’s families that would worry the servicemen. Ealidia Jones was also interested in servicemen’s welfare. The Filipina wife of Spanish-American War veteran John J. Jones made and sold candy, sandwiches, and other foods on the square in Marshall, with the proceeds going to the Red Cross in support of servicemen.

After World War II, veterans tried to restart the economy. A shirt factory and a library were opened in Marshall. Strawberry-growing in eastern Searcy County helped the economy until the mid-1960s when scarcity of pickers made it no longer profitable. Veterans tried to resurrect the pre-World War II proposal for dams on the Buffalo River, hoping it would boost the economy. They quickly clashed with canoe clubs, which mobilized opposition throughout Arkansas and adjoining states to stop the dams and to take the Buffalo and adjoining property by eminent domain, or under threat of eminent domain, and turn it into a national river. Some rural water districts in Searcy County that relied on wells found that their water contained such high quantities of eroding natural deposits of radium 226 and 228 that it was carcinogenic. However, environmental controls on the Buffalo River watershed prevented the building of a dam on the headwaters of tributary Bear Creek that would have provided safe water to rural water districts, and the threat of lawsuits over possible environmental degradation in part discouraged the creation of poultry-processing plants. Cattle-farming, timber-cutting, and wood products have provided most of the county’s income since the late 1970s. The Buffalo National River provides jobs and income through canoe rentals, cabins, and support services.

Famous Residents

The county has produced prominent people, including U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Jesse Smith Henley; Ulysses Simpson Bratton, who served as county judge and U.S. Attorney; country singer Elton Britt, whose song “There’s A Star-Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere” earned a gold record in the 1940s; painter Essie Ward, the “Grandma Moses of the Ozarks”; and children’s author Robbie Branscum. Stone County native Jimmy Driftwood, whose songs “Battle of New Orleans” and “Tennessee Stud” achieved platinum status, lived and taught school for several years in Searcy County.

For additional information:

Bishop, A. W. Loyalty on the Frontier or Sketches of Union Men of the South-West with Incidents and Adventures in Rebellion on the Border. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Clemons, Veda Mae, ed. Searcy County, Arkansas: A History of Searcy County, Arkansas. Marshall, AR: Searcy County Retired Teachers Association, 1987.

Compton, Neil. The Battle for the Buffalo River: A Twentieth-century Conservation Crisis in the Ozarks. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Johnston, James J. Searcy County Arkansas to 1850. Fayetteville, AR: 1991.

James J. Johnston

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Biplane Over Leslie

Biplane Over Leslie  Boston Mountains

Boston Mountains  Britt Songbook

Britt Songbook  Buffalo River

Buffalo River  Gilbert Train Depot

Gilbert Train Depot  Hurricane River Cave

Hurricane River Cave  Leslie Street Scene

Leslie Street Scene  Marshall Courthouse Square

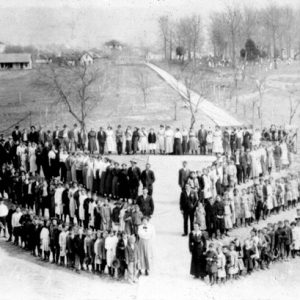

Marshall Courthouse Square  Marshall School

Marshall School  Marshall Strawberry Pickers

Marshall Strawberry Pickers  The Ozark Heritage Arts Center and Museum

The Ozark Heritage Arts Center and Museum  Searcy County Courthouse

Searcy County Courthouse  Searcy County Courthouse

Searcy County Courthouse  Searcy County Map

Searcy County Map  St. Joe

St. Joe  Essie Ann Ward

Essie Ann Ward  Zinc Furnace

Zinc Furnace

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.