calsfoundation@cals.org

Transportation

The systems of conveyance both through and within Arkansas involve routes that include land, air, and water. Because of Arkansas’s geographic location along the Mississippi, Arkansas, and Red rivers, water routes have been particularly important. Land routes have been much affected by the landscapes of the six natural divisions within the state, and achieving travel avenues of roads and railroads posed many problems, both for transportation through the state and among the divisions within the state.

Pre-European Exploration

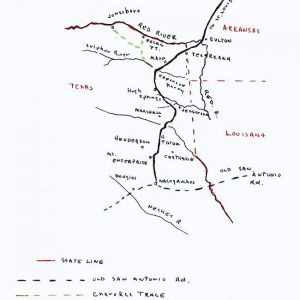

Paleolithic hunters who arrived in Arkansas more than 10,000 years ago appropriated trails beaten down by herds of mastodons and then bison. These trails became the basis for human societal development through transportation. The most significant land route, later called the Southwest Trail, ran along the edge of the Ozark escarpment from modern-day St. Louis, Missouri, south to modern-day Little Rock (Pulaski County). Then it followed the Ouachita escarpment south to Texas. Another important trail ran down the edge of the western plains, roughly paralleling Arkansas’s modern western border. A third land route ran along Crowley’s Ridge. Because of the difficulty in crossing a flood plain laterally, no major east-west trail seems to have crossed the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. Animals also created a network of local trails along streams, along the tops of ridges, and into valleys and springs.

Arkansas’s prehistory spanned more than 10,000 years and witnessed dramatic changes from hunter-gatherer cultures to sophisticated agricultural chiefdoms. Wide-ranging trade was central to these developments. Because stones suitable for making spear points were not universally available, stones from Missouri and from the Ouachita Mountains were carried overland for distribution. After 8500 BC, the introduction of a tool called the adz made it easy to construct canoes from single trees. Six forms, differing primarily in prow and bow designs, have been recorded, and trade increased greatly in consequence. Other traded items were fruits and vegetables from Mexico, seashells that came up from the Caribbean Sea, and copper that came from the Great Lakes. Just outside Fort Smith (Sebastian County) in Spiro, Oklahoma, is a site remarkably rich in trade goods because western and eastern tribes met and traded there.

European Exploration and Settlement

The Hernando de Soto expedition spent 1541 to 1543 in Arkansas. Along with boats constructed with nails, the Spanish brought horses and hogs. The arrival of French explorers Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet in 1673 promoted further French exploration by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, which itself led to Henri de Tonti’s creation of Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in 1686. During the French and Spanish colonial period (1686–1802) the Osage, from Missouri, met regularly with French and Spanish authorities where Cadron Creek empties into the Arkansas River. Historians presume that they had a direct land route down through the Boston Mountains in the Ozark Plateau.

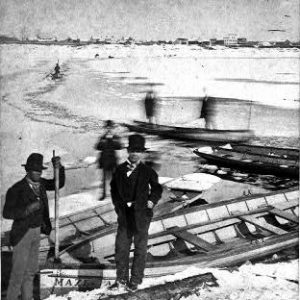

During the colonial period, a wide variety of watercraft were used in Arkansas. For local travel, boats called pirogues, each fashioned from a single log, were often large enough to carry passengers and freight. The bateau, of flat-bottomed construction with a roof-covered enclosed section in the rear, was superseded by the keelboat. These boats had a longitudinal board (the keel) attached to the bottom to keep the boat going in a straight line, making the boats easier to pole, pull, or paddle upstream. A combination of poling and pulling was more common than paddling when trying to move boats upstream, and most of the larger vessels also had sails. For poling, the boatmen used a pirogue to carry a rope up to a strong tree and then pulled the boat forward, staying in the eddies as much as possible. Six miles a day was considered good time on the faster rivers. In 1778, Spanish governor Fernando de Leyba took ninety-three days to ascend the Mississippi River by bateau from New Orleans, Louisiana, to St. Louis. It took only a quarter of that time to go downstream. Local residents also constructed flatboats for carrying cargo to New Orleans, where the boats were then broken up and sold for firewood.

Few improvements were made on land routes. The Spanish surveyed a road, known as the King’s Highway, from St. Louis down the west bank of the Mississippi River. The name and portions of the road itself are still in use today.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

After the Louisiana Purchase transferred Arkansas to the United States, the area’s population increased greatly. Most settlers from eastern states used combinations of water and land routes to come to Arkansas. One problem they encountered was that the Ouachita, White, Red, and Arkansas rivers, as well as other streams, were often of insufficient and inconsistent volume to support regular use. The first steamboats were patterned on eastern models and tended to experience problems when they left the Mississippi River, as they were designed for deeper waters. The Comet, the first steamboat to reach Arkansas Post in 1820, almost stayed lodged on a sandbar. Two years later, the Eagle reached Little Rock. Within ten years, however, steamboats were redesigned so that they needed only a few feet of water. The popularity of the steamboat was due to its speed, which could reach six miles an hour. Such boats plied the St. Francis, Ouachita, Black, Little Red, lower Buffalo, and Cache rivers, as well as other waterways, well into the 1930s. The federal government supported water transportation by clearing away “rafts,” or log jams, most notably on the Red River. An enormous rise in Red River land values and the expansion of plantation slavery into that region were directly due to the work of Captain Henry Shreve, whose snag boats cleared a passage through the enormous jam.

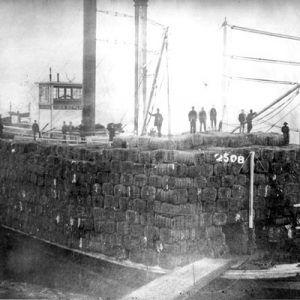

The ships on western waters were not as luxurious as those found on the Mississippi River. Shipwrecks were common, and one newspaper correspondent called the Arkansas River “the graveyard of steamboats.” The average life of a boat was only three years, but unless the boiler exploded, the engine was often salvaged. Much cotton went to market on these boats, but insurance rates were among the highest in America.

Because early Arkansas plantations were likely to be located along streams, planters put in their own wharfs, and, by dealing directly with far-away wholesale merchants, retarded the development of Arkansas towns. Canals, a prominent feature of internal improvements in the eastern states, were not suitable to Arkansas’s terrain. However, most travelers coming from the north accessed the Arkansas River via what was known as the White River cutoff, which became a ship canal in the twentieth century.

In addition to clearing waterways, the federal government also spent money on road improvement and construction. The first improvements took place on the Southwest Trail, which by 1818 was rendered suitable for wagon use as far south as Polk or Poke Bayou (later known as Batesville) in Independence County. From there, it continued on to Little Rock and then to Texas. New construction focused primarily on building a road from Hopefield (Crittenden County), opposite Memphis, Tennessee, to Little Rock. Difficulties abounded because the surveyors routed theroad through lowlands and swamps. The specifications called for the road to be twenty-four feet wide. Brush and saplings were to be removed, but trees had only to be cut to within four inches of the ground. Another survey extended the road to Fort Smith on the western border.

Ferry boats served in place of bridges. Steam ferries operated at Little Rock, Memphis, and Helena (Phillips County). The counties licensed such operations, and rates were fixed by the county courts. In 1846, the Little Rock Bridge Company built a private toll bridge over the Ouachita River at Rockport (Hot Spring County) only to have it washed away two years later. The principal rivers remained un-bridged until the twentieth century. Only a few privately owned toll roads existed by the end of the nineteenth century.

County governments oversaw the building of roads at the local level. Persons wanting a road in the vicinity of their land petitioned the county, and if the county court approved, the road was laid out. The county required that residents either pay a fee or work up to twelve days on building and maintaining the roads under the county’s direction. The first law entrusted enforcement and maintenance to “overseers.” Persons trying to avoid this onerous task were subject to fines. The absence of any year-round maintenance led to universal adoption of the folk custom of residents making paths around road damage and any obstacles in the road rather than fixing the problem. By the twentieth century, roads that once had been laid out straight had become winding routes. Because of its poor roads, Arkansas had poor mail service. The state’s well-earned reputation for discarded, damaged, and late mail retarded modernization.

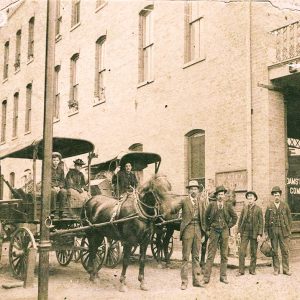

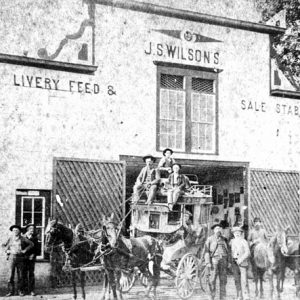

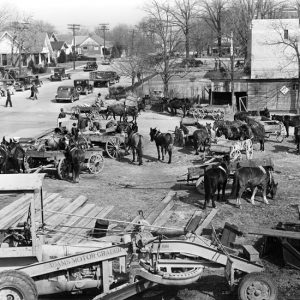

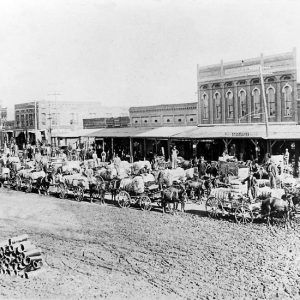

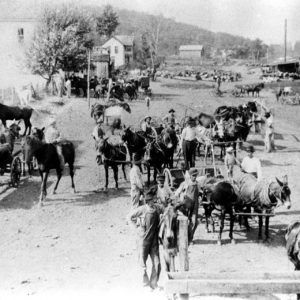

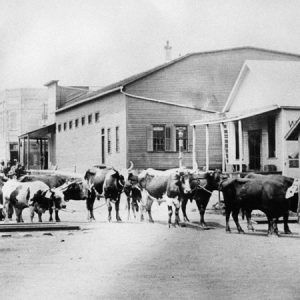

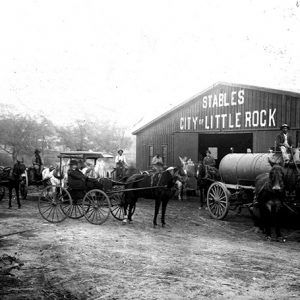

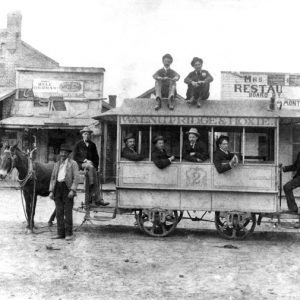

Horses were highly prized, both for riding and for pulling carriages and wagons. Many common people came to Arkansas in wagons pulled by oxen. A good team on a good day could average two miles an hour. Mules were somewhat faster. Many farmers could afford only mules instead of horses, so mules were used for hauling and ridden like horses.

In the nineteenth century, horse-drawn vehicles of various kinds were also known by a wide range of names. The terms “whimmy-diddle” and “go cart” were used, but perhaps the most common name for a public conveyance was “trick.” Farm wagons transported many people to town and church, while wealthier people had carriages. Fast-moving stagecoaches pulled by matched teams were as unknown as paved post roads. Passengers climbing the Boston Mountains to Fayetteville (Washington County) in were charged ten cents a mile but often had to get out and walk on the steepest grades. In 1858, this mountain route became part of the Butterfield’s Overland Mail Company’s famous western route.

Arkansas’s water and land routes were used during the federal government’s program of expelling eastern Native American tribes from their ancestral lands. Although the Cherokee migration is commonly spoken of as the Trail of Tears, the Cherokee used three land routes though Arkansas. Chief John Ross and many of the financially well-off members ascended the Arkansas River by steamboat. The Bell party took the road from Memphis to Little Rock and then followed the road that ran north of the Arkansas River. Another party bisected only the northwest corner of the state. The Benge party crossed the Mississippi River near Cape Girardeau, Missouri, and passed near Batesville and through Fayetteville. In addition, Choctaw, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Creek tribes all passed through the state on their way west. Much economic interchange accompanied the migrations and continued across the border, with the route west from Fort Smith into Indian Territory appearing on maps as the Whiskey Road.

Another use of Arkansas’s transportation modes came during the California Gold Rush. Fort Smith and Van Buren (Crawford County) were departure points for a southern route that eventually reached Salt Lake City, Utah. One section was known as the Cherokee route. Eastern gold seekers generally took steamboats to the embarkation points and there began their trek by wagon, horse, or foot across the continent. Arkansas cattlemen used this route to take herds to the California market. With the introduction of the telegraph in the state in 1860, a new term, “wire road,” came into use when poles followed the road right of way.

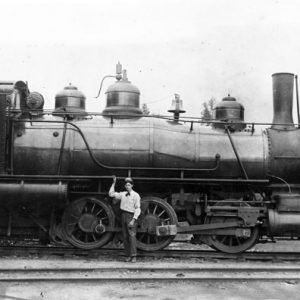

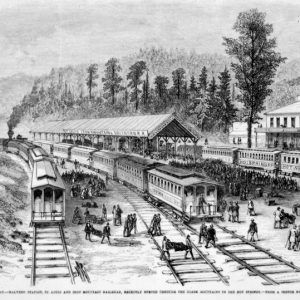

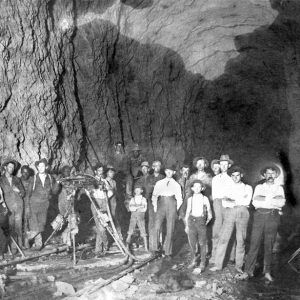

The construction of railroads became a critical issue in the 1850s. Whigs supported a state-financed railroad plan, while Democrats opposed it. In 1852, Democrat Elias Nelson Conway was elected governor on the oxymoronic platform of “good dirt roads.” However, the largely Whig merchant communities of Memphis and Little Rock pushed ahead with the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad. This project so infuriated citizens of Helena that Helena’s Masons refused to support Little Rock’s newly established Masonic institution, St. Johns’ College. Construction of this railroad was stopped due to the economic downturn in 1858. At the start of the Civil War, the section connecting Hopefield and the St. Francis River at Madison (St. Francis County) was complete, and substantial work had been done from Little Rock to DeValls Bluff (Prairie County).

The Democrats countered with the federally backed Cairo and Fulton Railroad. Cairo, Illinois, which envisioned itself as the great metropolis of the Midwest, was tied to Chicago, Illinois, via the Illinois Central Railroad and hoped to extend its reach into Texas. The Missouri division of the Cairo & Fulton began construction at Bird’s Point in Missouri and then headed west to the Ozark escarpment. Almost thirty miles were in service by 1861. Roswell Beebe was the principal promoter of the Arkansas section. The survey was complete, but construction did not come until after the Civil War. Today, the town of Beebe (White County) bears the name of Roswell Beebe.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The Civil War affected transportation in several ways. The Confederacy helped finance the completion of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad’s Little Rock to DeValls Bluff section. The war stopped all commercial riverboat traffic. The Union army invaded using river routes, but low water on the White River kept supply ships from reaching Union general Samuel Curtis’s army in the spring of 1862, forcing him to march overland to Helena. The 1865 explosion and sinking of the Sultana, an overloaded Union hospital ship, on the Mississippi River resulted in approximately 1,700 casualties, more than the Titanic disaster. Because of Arkansas’s legendary backwardness with regard to its infrastructure, General Frederick Steele’s invading army carried its own bridge. This pontoon bridge was finally abandoned after the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry.

During Reconstruction, Republicans provided state financing for railroads. With state aid, the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad completed the middle section between Forrest City (St. Francis County) and DeValls Bluff in 1871. However, its flood-prone Delta roadbed led to the rise of the legend of the “Slow Train through Arkansas.” Other state-funded routes included a line from Little Rock south to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and into the southeastern part of the state. The Mississippi, Ouachita, and Red River Valley Railroad got bogged down in the swamps and remained unfinished, which hampered economic development in southern Arkansas.

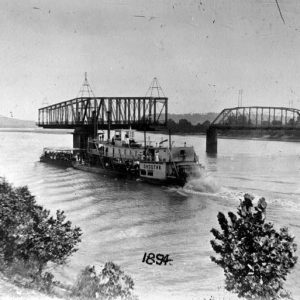

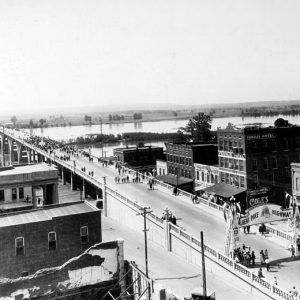

A Missouri railroad, the St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern (a.k.a. Iron Mountain), acquired the Cairo and Fulton Railroad interests in Arkansas in 1868. St. Louis, which viewed itself as the “Lion of the Valley,” diverted the main line from Cairo to St. Louis and greatly expanded its business in Arkansas. Railroad traffic increased greatly with the building of the Baring Cross Bridge across the Arkansas River in 1873.

The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, surveyed before the war, was completed. A national scandal over the marketing of its bonds undermined the political career of Republican presidential hopeful James G. Blaine, who became known as “The Continental Liar from the State of Maine” as a result. After the Democrats regained control of the state in 1874, Arkansas repudiated some $7 million of its railroad debts.

Post-Reconstruction through the Early Twentieth Century

Large sections of the Mississippi levee system had been destroyed in the Civil War and remained in a state of disrepair until the 1879 creation of the Mississippi River Commission led to major levee repair and new construction. Among the early projects was the rebuilding of the Maroon Swamp levee, first built in 1857, which kept Mississippi River floodwaters from entering the St. Francis River basin.

Meanwhile, a series of locks and dams made the White River navigable above Batesville. The construction of drainage ditches had a negative impact on water traffic on the St. Francis River, but at Marked Tree (Poinsett County), a siphon and lock kept some navigation alive on the St. Francis River into the 1950s. Railroads won decisive victories when, after the passage of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1909, most upkeep and improvements of the waterways were abandoned.

Between 1874 and 1910, numerous competing railroads sought prosperity. Thus the Iron Mountain cut into the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad’s market by building a better-suited route from Bald Knob (White County) to Hopefield. The Iron Mountain in turn faced competition from a narrow gauge line, the St. Louis and Southwestern (Cotton Belt), that paralleled to the east the older railroad and passed though Pine Bluff, turning that town into a major transportation hub. The Kansas City Southern ran along Arkansas’s western border, passing in and out of the state on its way south. The company created Mena (Polk County) as home for its central division shops in 1896.

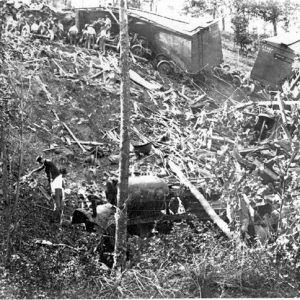

Building railroads in the Ozarks created the most problems. The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco) acquired the line running into northeast Arkansas by way of Mammoth Spring (Fulton County) and through Jonesboro (Craighead County) on to Memphis. The Frisco began what was supposed to be a connection to Texas. Starting at Pierce City, Missouri, it reached Fayetteville in 1881. In passing through the town, the railroad encountered the divide between the Boston Mountains and the Springfield Plateau. Slate had to be plowed and picked out, and the resultant alteration to the natural watershed resulted in considerable property damage and many lawsuits. To continue on to Fort Smith, the company had to build a tunnel near Winslow (Washington County).

Railroad magnate Jay Gould, owner of the Iron Mountain as well as most other Texas railroads, strangled the potential competition by buying the Frisco. A number of offshoots followed, as one promoter chartered the Fayetteville and Little Rock in 1886. The Frisco then purchased this line, which terminated at well short of its goal. The Frisco purchased this line, thus terminating it in St. Paul (Madison County), well short of its announced goal. Another venture tied Seligman, Missouri, to Eureka Springs (Carroll County), thus heralding two decades of growth for this spa town. The Eureka Springs line eventually expanded across northern Arkansas, reaching Berryville (Carroll County), Harrison (Boone County), Heber Springs (Cleburne County), and ending in Helena. Like most state railroads, it went through many bankruptcies and name changes, but the most remembered name, the Missouri and North Arkansas, acquired the nickname “Might Never Arrive.” This line faced competition from the Iron Mountain, which built a line up the White River valley through Batesville.

The arrival of a railroad shifted populations dramatically. Left dead were such once-notable towns as Rockport (Hot Spring County), Powhatan (Lawrence County), Jacksonport (Jackson County), and Wittsburg (Cross County). Sawmills and other business operations arose in newly created towns. Short line railroads, often owned by timber companies, sprouted all over the state. Lumbering in particular made use of short lines, spurs, and dummy lines. Once the lumber was cut, the rails were pulled up, and often even the towns disappeared. Every county except Newton County in the remote Ozarks had rail service by 1910. In the 1930s, the Missouri Pacific, successor to the Iron Mountain, created a bus company to supplement its rail passenger service.

The state’s last rail development, an attempt by the Cotton Belt Railroad to construct a St. Francis River valley system in the late 1920s, contributed to that line’s bankruptcy in the Great Depression and subsequent purchase by the Southern Pacific Railroad Co.

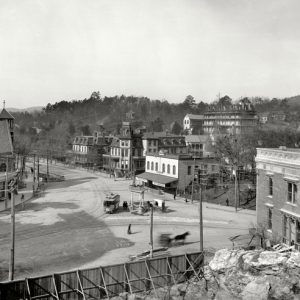

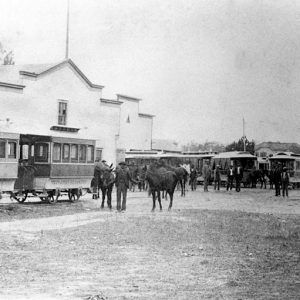

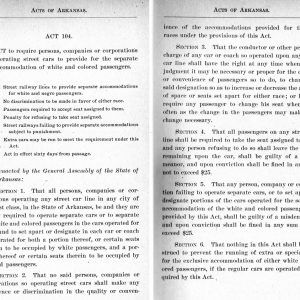

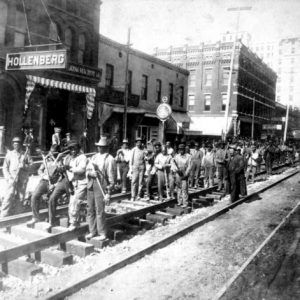

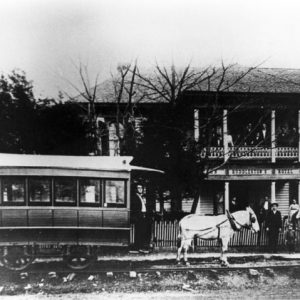

Trolley lines existed in Little Rock, Fort Smith, Hot Springs (Garland County), Eureka Springs, and even the small town of Sulphur Rock (Independence County). Trolley lines also connected Hoxie (Lawrence County) and Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County).

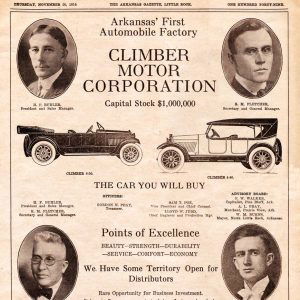

The movement away from “good dirt roads” began with arrival of automobiles in the new century. By 1903, some fifty vehicles could be found in Arkansas. By that time, the main streets of some towns were paved in brick, but most remained dirt. The Arkansas Good Roads Association was founded to lobby for progress in 1903, and the legislature authorized special road districts supported by taxes in 1907. The Dollarway Road from Pine Bluff to Little Rock was the first example of a modern road in the state. The state began numbering highways in 1917, and the Ozark Trails Association issued a map showing distances measured between white rings painted on trees and posts. By 1918, Arkansas had 190 miles of hard-surfaced roads.

Roads became the major political issue of the 1920s. By 1923, there were 113,102 vehicles, half of them Fords. The state was cluttered with 527 separate districts, with no coordination and high taxes. After the federal government stopped giving Arkansas any road money, the legislature passed the Harrelson Road Law in 1923, which gave control of roads to the state. The districts then secured the election of Governor John E. Martineau, whose plan consisted of the districts assigning their debts to the state. To pay these debts, Arkansas marketed new state bonds. The new money resulted in some better roads and new bridges, but the Flood of 1927 washed out 511 bridges and ruined miles of road. During the Great Depression, when Arkansas car owners were too poor to continue buying their licenses, the state became unable to pay the interest due on its bonds. When Arkansas halted payment on its bonds in 1933, the state became technically bankrupt. Although the people wanted highways, the politicization of the Arkansas Highway Commission resulted in cronyism, corruption, and fraud.

Aviation history in Arkansas had started with inventor Charles McDermott, who gave his name to the town of Dermott (Chicot County). This amateur scientist received from the U.S. Patent Office a patent for “Improvement in Apparatus for Navigating the Air” in 1872. After the Wright Brothers flew successfully, more than just balloons appeared in Arkansas. Air shows, in which pilots demonstrated their skills, and barn-storming, which often included taking local people up in planes to see the world from the air, preceded the use of airplanes for business and industry. The first recorded flight in Arkansas took place at Fort Smith on May 21, 1910, when pilot James C. “Bud” Mars took off in a Curtiss biplane.

The first mail carried by air in Arkansas (and the second such event in the nation) took place in Fort Smith in 1911. The U.S. Post Office instituted regular airmail service to Arkansas in 1931. World War I greatly furthered development of airplanes and resulted in the training of many pilots. Charles Lindbergh made the first night flight ever over Lake Chicot in 1923.

The burgeoning oil and gas industry hired many pilots to fly executives and petroleum engineers to their oil fields. The agriculture industry also took advantage of aviation. Crop dusting—dropping chemicals to kill boll weevils and other insects—was a luxury when first introduced in the 1920s.

Arkansas was also home to several small airplane manufacturers. In 1930, the short-lived Command-Aire of Little Rock built a plane that won the Cirrus International Air Derby.

World War II through the Modern Era

Air transportation grew enormously in the 1950s as rail travel declined. The federal Civil Aeronautics Board set markets and regulated fares. In order to make air transportation generally available, federal policy at first favored short hauls and encouraged the building of many local municipal airports.

While Arkansas had more than 100 public airports, the most important ones were at El Dorado (Union County), Fort Smith, Harrison (Boone County), Hot Springs, Jonesboro, Mountain Home (Baxter County), Pine Bluff, and Texarkana (Miller County). Construction on the Mena Intermountain Municipal Airport began in 1946; this Polk County airport was later implicated in drug smuggling and the Iran-Contra Scandal.

In 1978, the federal Airline Deregulation Act instituted massive changes to the passenger market. Many small markets had trouble maintaining service, for major carriers focused on a hub system that greatly disadvantaged hub-less Arkansas. Airfreight, which had operated under a similar system, was deregulated in 1977. Little Rock had regular service, but many outside central Arkansas had to commute to Memphis; Tulsa, Oklahoma; or other points outside the state. Population growth in northwest Arkansas resulted in the construction of the Northwest Arkansas National Airport in 1998, but only after years of controversy. Fayetteville’s Drake Field, nestled in the mountains, could not be expanded, and plans to create a regional airport by obliterating the Catholic settlement of Tontitown (Washington County) were met by a storm of local opposition.

Railroads responded to the increased competition from airplanes and automobiles by getting out of the passenger service. The closing of the Missouri and North Arkansas in 1946 significantly reduced access into the Ozarks, and cuts in schedules, maintenance, and upkeep on the remaining carriers followed. In 1970, Congress passed the Rail Passenger Service Act, creating Amtrak. Only one passenger route, along the old Southwest Trail, ran through Arkansas, and that on a limited schedule of three times a week. Deregulation that included abolishing the first federally created regulatory agency, the Interstate Commerce Commission, coincided with the collapse and final abandonment of the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad, the main parts of which were the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad and the Choctaw, Oklahoma and Gulf Railroad that ran through the Ouachitas. In the wake of deregulation, massive mergers resulted in the abandonment of hundreds of miles of track as the familiar corporate names of the past disappeared. By 2000, Arkansas had three Class I (national service) railroads with 2,714 miles of track and twenty-three Class III (local and regional) lines with 891 miles.

Water transportation was modernized greatly when the McClellan-Kerr Navigation System opened in 1971. This $1.2 billion project resulted in seventeen locks and dams that rendered the Arkansas River navigable year-round up to Catoosa near Tulsa. Other public terminals (loading stations) were located at Little Rock, North Little Rock (Pulaski County), Pine Bluff, and Fort Smith. The Army Corps of Engineers also maintained the Ouachita River as far upriver as Camden (Ouachita County). Terminals existed at Camden and Crossett. The Army Corps of Engineers maintained the White River up to Newport (Jackson County). The greatest amount of traffic could be found on the Mississippi River, and terminals were located in Osceola (Mississippi County), West Memphis (Crittenden County), Helena, and McGehee (Desha County).

Automobile travel blossomed after President Dwight D. Eisenhower endorsed a national interstate highway system. In 1956, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act, creating some 41,000 miles of interstate roads. Politics determined that Arkansas would get an east/west connection (Interstate 30 from West Memphis to Little Rock and Interstate 40 from Little Rock to Fort Smith), but the old Southwest Trail route became an interstate only from Little Rock to Texarkana. Interstate 55 passed only through Mississippi and Crittenden counties, and no interstate initially ran from Kansas City, Missouri, south to the Gulf. While interstates tended to follow the most ancient and most traveled routes, Arkansas experienced some problems. Interstate 55, which ran down from St. Louis and crossed the Mississippi River at West Memphis, made only a minor impact on the state. The portion of the old Southwest Trail between St. Louis and Little Rock was unfunded. However, Interstate 30 at Little Rock followed the old route into Texas. The former Memphis to Little Rock corridor became Interstate 40, and it extended to Fort Smith and beyond. The border route from Kansas City was not funded. Eventually, Interstate 49 was built from Alma (Crawford County) up to the Missouri state line, and interstate-quality construction extended from Little Rock to Newport. A new interstate linked Jonesboro to West Memphis.

Interstate roads provided new opportunities for agriculture and businesses. Over fifty per cent of Arkansas goods are moved by truck, and trucking is a major industry for the state. Arkansas became headquarters for major trucking firms such as J. B. Hunt and American (formerly Arkansas) Freightways. The Arkansas Trucking Association, founded in 1932, helped project the industry. In 2000, more than 1,800 regulated carriers operated in Arkansas; by 2014, this had increased to 4,860. In 2013, the trucking industry in Arkansas provided 83,210 jobs, or one out of eleven in the state. Total trucking industry wages paid in Arkansas in 2013 exceeded $3.5 billion, with an average trucking industry salary of $42,334, a figure that includes both drivers and non-drivers.

Though the growth of federal spending in the Depression era spurred some modest road construction, the chief problem facing the state was getting out from under the road debt of the 1930s. It was Governor Sid McMath (1948–1952) who got at least one paved road to every county. McMath’s enemies alleged abuses in the road program as a means to defeat his quest for a third term. The Arkansas Highway Commission, with one member for each of the state’s congressional districts, was the most politically powerful body in the state.

Heavy truck use meant that roads required constant maintenance, and with West Memphis being one of the nation’s busiest truck stops, the damage done to Arkansas interstates led the Arkansas Highway Transportation Department in 2002 to repair sixty percent (380 miles) of state interstate highways.

Recent transportation developments reflect three factors. First, Arkansas’s own products require access to markets. In addition to its agricultural exports—soybeans, rice, and cotton—Arkansas is one of the nation’s leading chicken-producing states. It also sends more than two million tons of sand and gravel out of state each year. Second, Arkansas supports its own homegrown transportation, primarily in trucking but also in locally owned barge lines and short line railroads. Finally, international developments continue to affect transportation patterns. Having a variety of transportation options and being centrally located benefit Arkansas. In cargo capacity, one river barge equals fifteen railcars and sixty trucks. Further, one ton of water-born cargo can be carried 514 miles on one gallon of petroleum fuel, compared to 202 miles by rail and 59 by truck. Rising energy prices plainly affected transportation patterns. The J. B. Hunt trucking firm led the way in 1991 by combining trucks and rail, using intermodal units for transcontinental service.

The Future

Trade between Latin America and the United States was projected to double between 2000 and 2020, and Arkansas is linked with this market in three ways. First, Interstate 30 and its extensions and connections provide a highway route. Second, while all major railroads passing through Arkansas have connections in Texas and Mexico, the Kansas City Southern system has major investments in Mexican railroads. Finally, Arkansas’s waterways are connected to the inland water system that reaches south to Brownsville, Texas.

Arkansas’s location in the lower middle states plainly favored the rise of trucking, and the state’s rail and river connections ensured that transportation jobs would continue to be an important source of employment. Rising gasoline prices have also raised the prospect that Arkansas’s agricultural crops could be converted into fuels, thus linking it further to the rest of the country and the rest of the world.

Bolton, S. Charles. “Missing the Train: Arkansas and the Pacific Railroad, 1848–1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 80 (Autumn 2021): 309–352.

Brown, Carl E. “Improving the Way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed December 18, 2025).

Cleek, Katherine Rose. “‘An Ample Provision for Our Posterity’: Transportation, Ceramic Diversity, and Trade in Historic Arkansas, 1800–1930.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2013. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/764/ (accessed December 18, 2025).

Chovanec, Zuzana, and Timothy S. Dodson. “The Early History of Streetcar Transportation in Little Rock, 1870–1948.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 54 (April 2023): 44–58.

Fair, James R. The North Arkansas Line: The Story of the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad. Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books, 1969.

Gooden, O. T. “Transportation.” In Arkansas and Its People: A History, 1541–1930, edited by David Y. Thomas. New York: American Historical Society, Inc., 1930.

Historic Review: Arkansas State Highway Commission and Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department, 1913–1992. Little Rock: Arkansas State Highway Transportation Department, 1992.

Huddleston, Duane, Walter J. Lemke, and Ted R. Worley. The Butterfield Overland Mail in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas State Archives, 1957.

Hull, Clifton E. Shortline Railroads of Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

Moffatt, Walter. “Transportation in Arkansas, 1819–1840.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Autumn 1956): 187–201.

Schwartz, Marvin. J. B. Hunt: The Long Haul to Success. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Wallis, Dave. Eight Nine Romeo Poppa: The Story of Arkansas Aviation. Pine Bluff, AR: Delta Echo Press, 2000.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

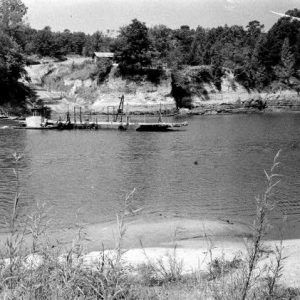

My mother took a photo of the Pendleton Ferry approaching the north bank of the Arkansas River in about 1948 or 1949. My family crossed on it many times when I was a child on our way to visit kinfolks. It was a floating steel barge that could carry four to five automobiles. The ferry was powered by a farm tractor mounted to starboard, and instead of wheels, the tractor turned large paddles on each side of the barge. The tractor clutches and brakes controlled the paddle wheels. When the river was low, the operator would build a plank road over the sand bars to load and unload his ferry. He got a bulldozer in 1949 or 1950, so the approach was easier after that. That ferry was a marvelous machine. It looked home-made, but it got you across the river just fine. It might have been a private business endorsed by the state department of transportation. The operator maintained approaches on both banks of the river. The ferry at St. Charles was more modern and was maintained by the state. There was a Coke icebox on board from which the operator sold five-cent icy sodas to drink as you crossed the river. He wanted the empty bottles back when you reached the other side.