calsfoundation@cals.org

Charles M. McDermott (1808–1884)

Charles M. McDermott was a medical doctor, minister, plantation owner, Greek scholar, charter member of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, and inventor. His patented inventions include an iron wedge, iron hoe, a cotton-picking machine, and a “flying machine.” He was a regular contributor to the Scientific American, and he was among the first to advocate the germ theory of disease.

Charles McDermott was born on September 22, 1808, in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. His parents, Emily Ozan McDermott and Patrick McDermott, owned sugarcane plantations. He had four brothers and two sisters. It was at the plantation home, Waverly, where McDermott became interested in flying. McDermott entered Yale University in 1825 and obtained a bachelor’s degree with honors in 1828.

On December 9, 1833, he married Hester Susan Smith in New Roads, Louisiana. He then studied medicine with his brother-in-law, Dr. Baines, and began a medical practice. The McDermotts had sixteen children and raised four of McDermott’s brother’s children.

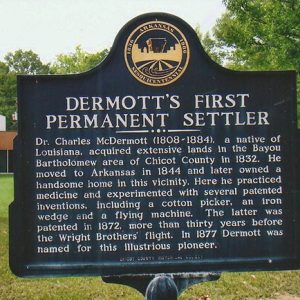

While visiting Mississippi, McDermott heard of the rich land in Arkansas’s Chicot County and traveled to investigate it. He bought a large tract of land, which is now in Dermott (Chicot County), in 1834 and established a plantation, to which the family moved in 1844. After living in cabins on the bank of Bayou Bartholomew for seven years, the McDermotts moved into their new home, Bois D’Arc, which was designed after Louisiana houses of the period. The home was on the Gaines Landing Road and became a hospitality house for immigrants. McDermott built a new manor, Finisterrae, where the family lived during the summer, near Monticello (Drew County) in 1858.

After the Civil War, he returned to the bayou plantation to begin farming. Becoming discouraged, the staunch Democrat moved his family to Honduras. After his attempt to establish a secessionist colony failed, he came back to the plantation, where he turned his attention to inventing. He received patents on a cotton-picking machine in 1874, the common iron wedge in 1875, and an iron hoe. His main goal, however, was to build a flying machine.

Observing the flight of birds, especially buzzards and cranes, McDermott noted how they glided for long periods of time without flapping their wings. He determined that man, too, should be able to fly. He said, “I hope to give a flying chariot to every poor woman,” and he believed that he had found the key to flight: “Many (birds) sail one above the other, and a horizontal propulsion is the secret which was never known until I discovered it by analysis and synthesis, and which will shortly fill the air with flying men and women.” His experimental designs were essentially gliders in the fashion of biplanes, tri-planes, and multi-planes.

He split cypress slats by hand, connected them with wire, and attached silk between the slats for the wings. Lying prone on a hammock within the apparatus, he gained propulsion by pedaling his feet to augment the power from the wind. He wrote in his patent application: “The operator places himself upon the support with his face upward, his feet connected to or with the cords for actuating the propeller, and the cords of the guiding vanes in his hands, in which position he is enabled, by alternately drawing and extending outward his legs, to give a forward motion to the machine, while by means of the guiding-vane, the course of the same is also controlled.” To get airborne, he employed boys to hold the device until he was ready to begin pedaling with the wind or attempt take-offs from rooftops. Some of his models actually flew a short distance. Feeling confident at last, he hauled a machine by wagon to Washington DC to apply for a patent, which he received after thirty-nine years of experimentation, and it is believed to be the first patent for an airplane. His patent, “Improvement in Apparatus for Navigating the Air,” was granted on November 12, 1872.

McDermott became an advocate for the promotion of air travel, once staying in Washington for nine months in this effort. He exhibited his models at the Southeast Arkansas Fair in Monticello in 1874, the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1876, and the Arkansas State Fair in Little Rock (Pulaski County). It is assumed that later inventors used information from McDermott’s patent. When the Wright brothers made their successful fifty-nine-second flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903, two men in the audience are believed to have said, “Why, that’s Charlie McDermott’s machine!” After the Wright brothers’ flight, an article in the Scientific American described McDermott’s machine and accredited his plans to their success. If McDermott had had the advantage of the gasoline engine for propulsion, he might have been the first to fly. The Institute of the Aeronautical Society in New York City acknowledges his inventions, and a model of his machine was on display at the Arkansas Aerospace Education Center.

McDermott died on October 13, 1884, of a spinal disease at his home on Bayou Bartholomew in Dermott, the community that bears his name. He is buried in a marked grave in the family cemetery that is on the former plantation grounds.

For additional information:

Atkinson, J. H., ed. “A Memoir of Charles McDermott.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Autumn 1953): 253–261.

DeArmond, Rebecca. Old Times Not Forgotten: A History of Drew County. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1980.

DeArmond-Huskey, Rebecca. Bartholomew’s Song: A Bayou History. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2001.

Kinney, A. F. “125 Years of History Woven into a Short Story.” Arkansas Democrat Sunday Magazine, February 17, 1952, pp. 8–10.

———. “Arkansas Flying Machine Inventor.” Arkansas Gazette Sunday Magazine, October 5, 1941, pp. 8–9.

Teske, Steven. Unvarnished Arkansas: The Naked Truth about Nine Famous Arkansans. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Rebecca DeArmond-Huskey

Wilmar, Arkansas

Aviation

Aviation Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Science and Technology

Science and Technology Charles McDermott

Charles McDermott  McDermott Marker

McDermott Marker

We lived in Dermott, Arkansas, in the 1960s, and our son Don was born there in the Dermott Catholic Hospital. My husband was the pastor of Dermott Baptist Church.

Thank you for recognizing my great-great-grandfather, Dr. Charles McDermott (1808-1884) of Dermott, Chicot County, Arkansas. A chapter has been devoted to Dr. McDermott in Steven Teske’s book, Unvarnished Arkansas: The Naked Truth about Nine Famous Arkansans and in Tom Dillard’s book, Statesmen, Scoundrels and Eccentrics, A Galaxy of Amazing Arkansans.

Although he practiced medicine, his greatest passion was invention and especially the possibilities of human flight. His 1872 airplane patent (Improvement In Apparatus For Navigating The Air) is believed to be the first airplane patent granted by the U.S. Patent Office.

British engineer Edward Butler constructed the first gasoline internal combustion engine in 1884. The irony is that “Flying Charlie” died in 1884 never knowing about this invention. With the gasoline internal combustion engine at his disposal, I am sure that “Flying Charlie” would have been the first to take flight right there in the fields of Chicot County.

He must be related to us because there is spinal degenerative disease in this line also. Very smart man.