calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas's Exhibitions at the World's Fairs

In 1876, the United States hosted its first World’s Fair in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence: the United States Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. International expositions, or World’s Fairs, emerged from the Great Exposition in London in 1851, which primarily focused on industrial innovation. World’s Fairs in the United States invited participation from each state, with each state funding its own building and displays. Arkansas’s participation in numerous World’s Fairs in the United States presented an opportunity to advertise the state’s accomplishments and promote settlement. While Arkansas participated in a number of World’s Fairs over the years, the most significant expositions occurred around the turn of the century.

The Centennial Exposition (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1876)

In 1875, Governor Augustus H. Garland recommended an appropriation by the legislature to ensure that Arkansas participated in the Centennial Exposition, seeing it as an opportunity to encourage immigrants to come to the state, and therefore increase the state’s population and wealth. The state legislature appropriated $15,000 to cover expenses for Arkansas’s display in the Centennial Exposition. Other means of fundraising also took place, as the legislature’s appropriation was likely to come late in preparing Arkansas’s exhibits. The Women’s Centennial Club held events to raise money, and individual contributions supplemented state funding.

The octagonal Arkansas building and the displays within it highlighted the state’s natural resources, including native woods, minerals, and agricultural products. The building itself was constructed entirely from native Arkansas woods, and individual pieces of furniture commissioned to decorate the interior were composites of many types of wood. A counter made of gum wood consisted of more than 3,000 individual pieces. Its decorations of hand-carved flowers, leaves, vines, and berries were all carved in different-colored woods. A cabinet made for the display of crystals from Hot Springs (Garland County) contained more than 2,000 pieces of Arkansas wood. The cabinet included a bookcase with 200 carved “books,” their spines identifying the type of wood. No paint was used on the furniture to further highlight the natural beauty of the varieties of woods. A large bronzed iron acanthus fountain donated by the Little Rock and Pine Bluff Women’s Centennial Club adorned the center of the octagonal exhibition room. It ended up at the Old State House in 1878, along with three statues representing Law, Mercy, and Justice, and the state’s coat of arms.

Cotton plants by the thousands were also displayed, and visitors took cotton bolls as souvenirs, as well as sacks of shelled corn. Arkansas received two awards from the Memphis Cotton Exchange. A variety of minerals on display included iron, zinc, silver, copper, lead, granite, limestone, kaolin clay, coal, and more. Coal from several counties including Johnson, Pope, Yell, and Sebastian ranked at the same level as coal from Pennsylvania and Ohio, demonstrating Arkansas’s mineral resources as worthy competition.

The Arkansas women’s reception room exhibited portraits of prominent Arkansans such as Chester Ashley and Sandy Faulkner, as well as a painting titled The Arkansas Traveler, complemented with the “Arkansas Traveler” tune played on a piano. The painting is identified as a copy of Edward Payson Washbourne’s The Arkansas Traveler painted by James Fortenbury; one woman commented that “the painting might give the wrong impression of Arkansas people,” demonstrating the controversial nature of the hillbilly image it portrays.

Also displayed were Native American arrowheads, pottery, and other tools found in various mounds across the state. A historic land deed signed by King George II in 1737 was added to the state building’s collection. It was sent by Judge P. O. Thweatt of Phillips County and originally belonged to his great-grandfather. Rebecca Washington of Washington County crocheted an unusual lace scarf, using silk from silkworms that she raised herself on mulberry leaves. Although displayed in the Woman’s Pavilion rather than the state exhibit, the butter sculpture Dreaming Iolanthe made by Caroline Brooks, resident of Helena (Phillips County), attracted considerable praise and attention. As people began to question its authenticity, she recreated it as a special demonstration of her technique. Brooks may have inspired future butter sculptures on a larger scale that appeared in subsequent state and world fairs.

The Columbian Exposition (Chicago, Illinois, 1893)

Originally planned to open in 1892 to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to America, the Columbian Exposition in Chicago opened a year late in 1893. The Arkansas World’s Fair Association met in 1891, and the Board of Trade endorsed Arkansas’s participation in the Columbian Exposition. The aim was again to encourage settlers to move to Arkansas. Printed at the end of the Board of Trade circular, an ad for the “Cheapest and Best Land in the United States” announced the availability of 19,000 acres of government land and invited readers to “Come to Arkansas and get a Home!”

However, in the early planning stages of 1891, an appropriation to fund Arkansas’s exhibition was not supported by the legislature, and citizens instead bought stock in the state’s World’s Fair Association to contribute the necessary funds to make Arkansas’s display a success. In 1893, the state Senate passed a bill in support of an appropriation of $30,000 to finish the work already begun on Arkansas’s exhibitions. At this point, Arkansas’s participation in the World’s Fair was in question. If the appropriation were again rejected (as it had been in 1891), the Arkansas building’s debts were in danger of going unpaid, and the building would have to be sold. Despite the support of the Senate, the bill was defeated by the House of Representatives. Reasons for opposing the bill varied. Some debated the amount or how it should be spent; others completely opposed spending tax money to fund exhibit expenses or suggested it would be better spent on current residents of the state rather than bringing in “foreigners.” Eventually, a reduced appropriation of $15,000 was agreed upon.

Arkansas women were called to serve on the Board of Lady Managers, whose duties consisted of fundraising for the association, organizing exhibits for the art department, and decorating the interior of the Arkansas building. Jean Loughborough-Douglass designed the state building itself, the construction costs totaling $13,500. The Arkansas building is described as either French Rococo or Renaissance style. The Renaissance characteristics are visible in the semicircular arcade of rounded arches at the entrance. Natural, curvilinear ornament distinguishes the Rococo and generally focuses on the interior. These decorative elements are also visible on the exterior, framing the arches and running along the top of the arcade. Part of the frieze that decorated the interior survives today in the parlor of the Drennen-Scott Historic Site home in Van Buren (Crawford County), once the home of Fannie Scott, who served on the Board of Lady Managers. A central rotunda allowed natural light to come in through a glass dome. Six rooms bordered the rotunda. Five were exhibit rooms, and the sixth was a registry room for visitors near the entrance. Scattered throughout the building interior were vases, columns, and a large mantel made of Arkansas white onyx, illustrating the quality of the natural stone. The second floor consisted of parlors for men and women, a library featuring Arkansas authors, and committee and officers’ rooms. A local woman from Camden (Ouachita County) created a plaster bust of General Albert Pike for the exhibit.

A 14,000-pound piece of zinc from Marion County, measuring six feet long, seven feet wide, and four feet thick, displayed the potential wealth in Arkansas’s minerals. Initially planned to be placed in front of the Arkansas building, the giant piece of zinc instead went into the Mining Building to be compared on a national scale.

A major focus of the Columbian Exposition was electricity. In the center of the rotunda’s court, a fountain designed by Sarah Ellsworth of Hot Springs featured crystals from the area. Granite from Little Rock (Pulaski County) formed the ten-foot diameter basin of the fountain. A sketch of the fountain’s design shows a cherub in the center holding up a large flower, sitting on a rock and surrounded by a bed of crystals. Hubert Bancroft’s Book of the Fair describes the flower petals as studded with tiny crystals and the fountain lit by electricity. Although other fountains at the exposition had electric lighting, this illuminated fountain may have referenced the thermal baths for which Hot Springs is so well known. Remnants of a plaster cast model in Ellsworth’s home in Hot Springs were left in the attic or servant’s quarters and match the figure’s form in the sketch of the fountain. As the fountain’s designer, Ellsworth oversaw the fountain’s construction, and the model of the cherub was made by Caroline Brooks, the butter sculptor. Published and sold to help raise funds, a pamphlet titled “Arkansas and Her Passion Flower at the World’s Fair in 1893” contained a description of the crystal fountain along with detailed descriptions and pictures of the Arkansas building.

Arkansas’s natural resources were once again the inspiration for display furniture. The J. G. Miller & Co. table factory of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) made an armchair and whatnot cabinet for the Arkansas building. The whatnot features more than fifteen types of Arkansas wood. Both pieces of furniture are now on permanent display at the Fort Smith Museum of History. Another demonstration of the forests in Arkansas was a specimen of oak that measured 125 feet high and thirty-three feet in circumference at one foot above the ground, said to rival California’s “Hooker Oak.” A large relief map of Arkansas made by state geologist John C. Branner outlined the locations of the mineral deposits, timber, prairies, and swamp lands, acknowledging the diversity of the resources within the state.

Apples and cotton placed in Agricultural Hall, as well as zinc in the Mining Building, competed against products from other states and demonstrated either equal or superior quality. In the end, Arkansas won twenty awards in the Educational Department, first place for the zinc carbonates from Marion County that were placed in the Department of Mines and Mining, and two awards for long- and short-staple cotton, as well as first-place awards for apples. Inspired by Arkansas’s display, the musical DeMoss family composed the song, “My Happy Little Home in Arkansas.” The song described Arkansas as “ever green” and where “famous premium apples grow,” and as a place that grows cotton, cane, and every kind of grain.

Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis, Missouri, 1904)

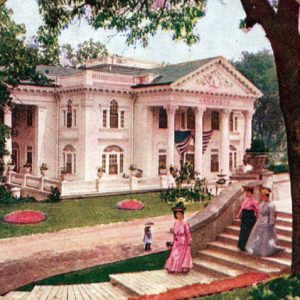

The 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, celebrated the Louisiana Purchase. Construction of the state building continued to utilize products of the state as a testament to its wealth of natural resources. It was built in the Neoclassical style by Frank W. Gibb of Little Rock, with triangular pediments and four Corinthian order columns extending onto porticoes creating two entrances. A painted frieze of apple blossoms inside acknowledged the recently adopted state flower. Arkansas artist and mural painter Paul Martin Heerwagen, who decorated the Arkansas State Capitol at Little Rock, painted the interior decoration by hand.

While the previous fairs documented state buildings and their displays in more detail, descriptions of the Arkansas building at the St. Louis fair are brief. However, several photographs from the 1904 World’s Fair Collection at the Old State House Museum in Little Rock document Arkansas’s participation in other buildings throughout the exposition. A grandfather clock crafted of more than twenty-five varieties of Arkansas wood and decoratively inlaid with 50,000 pieces is part of this collection. The contrast of light and dark woods forms geometric patterns on the panels.

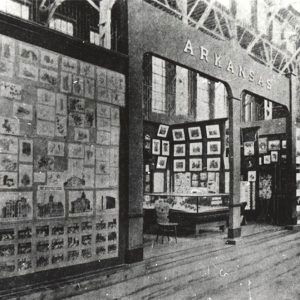

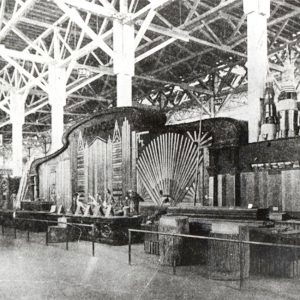

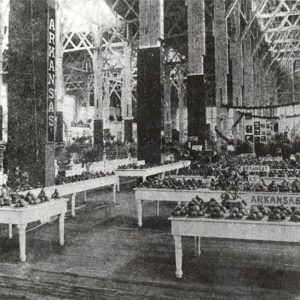

The Arkansas Mines and Metallurgy display in the Palace of Mines and Metallurgy included aluminum ore, Arkansas bauxite, phosphate rock, coal from the Consolidated Anthracite Coal Co. in Spadra (Johnson County), and cases of quartz crystals. The Arkansas Forestry Exhibit in the Forestry, Fish, and Game Building showed a variety of boards and tree samples combined with crafted wood objects. The display backdrop itself was constructed out of twigs, forming rustic-looking arches, column capitals, and a scroll framework for the back display wall, with “Arkansas” prominently labeled at the top. To the left of the picture, stuffed owls and cranes illustrate Arkansas wildlife. Arkansas’s Agricultural Exhibit in the Palace of Horticulture featured tables of fruit and vegetables, jam and jelly, and possibly wine. Apples filled numerous tables on “Apple Day,” again winning awards for quality fruit.

The Land Department of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern and the Little Rock and Fort Smith railways published a series of pamphlets describing Arkansas lands and what they have to offer. Titles addressing the state’s orchards, agriculture, stock raising, minerals, timber resources, and manufacturing opportunities, as well as descriptions of sections of the state, all aimed to increase the population and instigate growth and development—especially the pamphlet “Get a Home in Arkansas.” After the exposition ended, A. F. Wolf purchased the Arkansas building, and it was reconstructed in Fayetteville (Washington County) at Mount Nord to serve as a private residence. It was torn down in the late 1930s.

The World of Tomorrow (New York, New York, 1939–40)

Arkansas also participated in a few other fairs on a small scale—World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial (New Orleans, 1884–85); Cotton States and International Exposition (Atlanta, 1895); Trans-Mississippi International Exposition (Omaha, 1898); and the Golden Gate International Exposition (San Francisco, 1939)—but these are not as well documented. While there were a few other international expositions hosted by the United States in the early twentieth century, Arkansas’s participation in another major fair occurred in 1939 with The World of Tomorrow in New York. Unlike the earlier displays, the state’s participation in this fair was funded by individuals and businesses rather than with tax money. The later exhibits continued to appeal to those looking for homes and to give the state good publicity, but the state’s display at this exposition focused more on advertising tourism as well as Arkansas life—which consisted of pastures, cotton and rice fields, peach orchards, strawberry fields, schools, scenic mountains, lakes, and forests, as well as busy cities offering diverse prospects. Rather than physically bringing examples of the state’s products, as was done in the past, The World of Tomorrow relied more on images. There were more photographs, film reels, and paintings to illustrate Arkansas than actual products. The artist Adrian Brewer produced fifteen oil paintings of Arkansas landscapes. The main attraction in the state building consisted of two films called “Life in Arkansas” and “Forward Arkansas” showcasing the state’s resorts, scenery, education, agriculture, game and fish, and industrial investment opportunities.

Although it was not directly a part of Arkansas’s exhibits, William Grant Still, a well-known African-American composer who grew up in Little Rock, wrote the theme music for the New York World’s Fair, “Song of a City.”

African-American Participation

Such exhibitions of “progress” as the World’s Fairs did not readily include African-American accomplishments since Emancipation, and African Americans fought discrimination and exclusion from the fairs from the beginning. Arkansas’s exhibits were no different. As reported in the Arkansas Gazette, the state exhibit in 1893 presented an educational display that included student work from Arkansas’s “colored” schools. The only other mention of African Americans directly involved in state exhibits is in 1902, when the Arkansas Negro Department formed to represent Arkansas’s black citizens in the upcoming St. Louis fair. Although none of the final publications mention any displays by the Negro Department, additional research needs to be conducted in this area.

Conclusion

While other states with more established histories focused on a particular moment or national figure in their buildings, Arkansas’s exhibits throughout all of the World’s Fairs encompassed the state’s varied resources, ancient history, and promising future. All of the exhibits portrayed the state as self-sufficient and with much potential for economic development.

For additional information:

“Arkansas at the World’s Fair.” Little Rock: Arkansas World’s Fair Association, 1893.

Arkansas in 1892–1893: Prepared from Data Obtained from the Census Returns of 1890, and Other Authoritative Sources for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Little Rock: Diploma Press, Arkansas Democrat Co., 1893.

Cahill, Bernadette. “Pulaski Women and the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893.” Pulaski County Historical Review 66 (Winter 2018): 148–155.

“Columbian Exposition: Arkansas Must Be Represented.” Columbian Exposition Papers, 1891–1893. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Hudgins, Mary D. “A Fabled ‘Folk Song.’” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Winter 1975): 352–360.

———. “Sarah Ellsworth: Maker of Arkansas History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 11 (Summer 1952): 102–112.

Hudson, Ralph M. “Art in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 3 (Winter 1944): 299–350.

Official Guide to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition at the City of St. Louis, State of Missouri, April 30th to December 1st, 1904. Compiled by M. J. Lowenstein. St. Louis: The Official Guide Co., 1904. Online at http://openlibrary.org/books/OL23505904M

/Official_Guide_to_the_Louisiana_Purchase_Exposition_at_the_City_of_St._Louis_ (accessed January 24, 2022).

Sherwood, Diana. “Arkansas at the First World Fair.” Arkansas Gazette Magazine, May 27, 1934, pp. 1, 11.

Simpson, Pamela H. “Caroline Shawk Brooks.” Women’s Art Journal 28 (Spring–Summer 2007): 29–36.

White, Trumbull, and William Iglehart, et al. The World’s Columbian Exposition: A Complete History of the Enterprise; a Full Description of the Buildings and Exhibits in all Departments; and a Short Account of Previous Expositions. Philadelphia: International Publishing Co., 1893. Online at http://www.archive.org/details/worldscolumbiane00whit (accessed January 24, 2022).

Wilson, Bobby G. “1904 World’s Fair, St. Louis—Part Two.” Flashback 43 (November 1993): 31–38.

World’s Columbian Exposition. The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition, May 1st to October 20th, 1893: A Reference Book of Exhibitors and Exhibits; of the Officers and Members of the World’s Columbian Commission, the World’s Columbian Exposition and the Board of Lady Managers; a Complete History of the Exposition. Chicago: W. B. Conkey Co., 1893.

Alana Embry

University of Arkansas at Fort Smith

Arkansas's Image

Arkansas's Image Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Recreation and Sports

Recreation and Sports Agricultural Exhibit

Agricultural Exhibit  Arkansas Building

Arkansas Building  Arkansas Building, 1876

Arkansas Building, 1876  Arkansas Day

Arkansas Day  Arkansas Exhibition

Arkansas Exhibition  Arkansas State Building

Arkansas State Building  Arkansas State Building, 1907

Arkansas State Building, 1907  Caroline Shawk Brooks

Caroline Shawk Brooks  Educational Exhibit

Educational Exhibit  Forestry Exhibit

Forestry Exhibit  Horticulture Exhibit

Horticulture Exhibit  Mines and Metallurgy Exhibit

Mines and Metallurgy Exhibit

The St. Louis building was bought by my great-uncle A. F. Wolf and moved to Fayetteville. He was a prominent builder. A building in downtown Fayetteville has his name on the cornerstone.

According to a 1935 book published by the US DOI, Arkansas probably sent at least three other pieces of ore to the St. Louis Expo of 1904.

On p. 162, it says that Panther Creek Mine sent a sample of 5,200 lbs. of jack, which is a type of zinc ore, generally called sphalerite, chemical formula ZnS.

On p. 264, it says the Washington Lead Co. sent a sample of pure galena (lead ore) weighing 1800 lbs.

On p. 282, it says Marble Falls Mine sent a sample of jack weighing about a ton.

All of these mines are in Marion County.

The book also mentions the 14,000 lbs. of turkey fat (Smithsonite zinc ore) sent by the Morning Star Mine to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

From Zinc and lead deposits of northern Arkansas Bulletin 853

By: Edwin Thor McKnight

Publication: http://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/b853