calsfoundation@cals.org

Caroline Shawk Brooks (1840–1913)

Caroline Shawk Brooks was the first American sculptor known to have worked in and mastered the medium of butter. She eventually became known as the “Butter Woman.”

Caroline Shawk was born on April 28, 1840, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Abel Shawk and Phoebe Ann Marsh Shawk. She married Samuel H. Brooks in 1862, and the couple moved to Helena (Phillips County) in 1866, where Samuel Brooks owned and worked a cotton farm. They had one daughter, Caroline Mildred (1870–1950); she married Walter C. Green, a trained stonecutter who did most of the marble cutting for Caroline Brooks when she began to work in that medium.

In 1867, the cotton crop failed. To supplement the family income, Caroline created her first butter sculpture. Farm women of the nineteenth century often shaped home-churned butter into decorative designs using butter molds; this pressed butter was then used or sold. Instead of molds, however, Brooks shaped butter into complex figurative shapes using non-traditional tools such as cedar sticks, camel’s hair pencils, butter paddles, and broom straws.

Brooks started sculpting small creations such as shells but eventually tried to depict her friends’ and family’s faces, increasing the size of her designs. By 1865, ice houses had sprung up across the South, and locals had regular access to it. Using a steady supply of ice, Brooks could preserve her vulnerable creations for long periods of time.

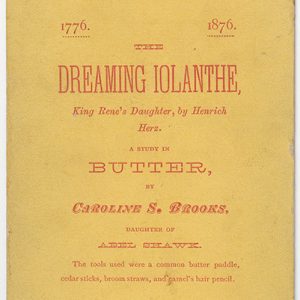

In 1873, Brooks was inspired by the verse drama King Rene’s Daughter by Danish playwright and poet Henrik Hertz. The story revolves around the king’s daughter, Princess Iolanthe, who is born blind but raised to be unaware of her own condition. However, on her sixteenth birthday, Iolanthe discovers the truth that her parents tried to hide. Brooks made a butter sculpture depicting the princess right before she discovers her blindness. Dreaming Iolanthe exhibited in a Cincinnati gallery in 1874 and quickly became a success, with 2,000 people paying to see it during the show’s two-week run. An April 4, 1874, article in the Cincinnati Commercial described the bust of Iolanthe: “The butter is almost white. Its translucence gives to the complexion a richness beyond alabaster, and a softness and smoothness which are very striking. The hair ripples back in waves, and the lips are parted with a heavenly smile.”

Shaping and preserving her butter art presented certain challenges. She constructed most of her relief sculptures in flat, metal milk pans. These smaller pans were placed in larger pans that were continually refilled with ice. In Helena, Brooks used a metal table in her kitchen, which could be iced down as she worked.

In the years following her Cincinnati debut, Brooks created many other versions of Iolanthe, including a nine-pound bas-relief for the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. This work traveled over a thousand miles from her kitchen table to the Women’s Pavilion at the exhibition. Her unique artwork and engaging personality drew huge crowds. She was so popular that she was invited into the main exhibition space to demonstrate her butter sculpting abilities.

Even though the invitation to demonstrate her craft was considered an honor, it was probably partially motivated by skepticism rather than admiration. Historically, cultural attitudes supported the belief that only academically trained white men could produce high-quality fine and decorative arts, and female artists were frequently accused of attaching their names to artworks created by men. To prove she was the artist behind the butter princess, Brooks formed another head from butter in about ninety minutes. This public performance took place in front of exhibition officials and members of the press, leaving no room for anyone to doubt her prowess as a sculptor.

Following her success at the Centennial Exhibition, Brooks toured the country giving lectures and demonstrations. Her artistry eventually took her to Europe, where she traveled and worked in various studios. In 1878 and 1889, she showcased at Paris exhibitions. Between these expositions, Brooks had her butter sculptures cast in plaster and then meticulously carved in marble by Italian stonemasons. While in France, she was stopped by a customs agent and asked to explain a butter sculpture amongst her shipment. She identified the butter as artwork, but the agent listed the work as simply 110 pounds of butter.

In 1893, her butter-work debuted in Chicago at the World’s Columbian Exposition, in the Arkansas building. Brooks stated in a September 12, 1893, interview with J. B. Parke, “I am an Arkansas artist, and proud of it. It was on our plantation in Phillips County, just nine miles from Helena, that I made my first nine pounds of butter and modeled it into the figure that gave me fame. And the people there called it—‘The Butterhead!’ Now I like that name, but didn’t then.”

During her career, Brooks made many sculptures for patrons and politicians. She invented a method to create a mold of her butter sculptures: by applying plaster around a sculpture, then heating the sculpture and melting the butter away, she was left with a plaster mold that could be used to create multiple casts of the original sculpture in butter, clay, or other pliable media.

In 1902, Brooks was accepted by the Grant statue commission to create a sculpture of President Ulysses S. Grant. People were aghast that the “Butter Woman” had been accepted into the competition. Though her design was not chosen for the final commission, using her innovative plaster mold method, she built the design in butter before casting her submission in plaster. Despite public protest, Brooks received many awards around the world for her sculptures in butter and other more traditional media. Her acclaim opened the doors for future female sculptors, which was noted by many publications during the last ten years of the artist’s life.

Caroline Brooks died on June 28, 1913, and is buried in the Oakdale Cemetery in Lemay, St. Louis County, Missouri.

For additional information:

“Caroline Shawk Brooks.” Arkansas Made Research File. Historic Arkansas Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Ingram, J. S. The Centennial Exposition, Described and Illustrated. Philadelphia: Hubbard Bros, 1876.

Kirkman, Dale P. “Caroline Shawk Brooks: Sculptress in Butter.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 5 (March 1967): 8–9.

Simpson, Pamela H. “Butter Cows and Butter Buildings: A History of an Unconventional Sculptural Medium.” Winterthur Portfolio 41, no. 1 (2007): 1–20.

———. “Caroline Shawk Brooks: The ‘Centennial Butter Sculptress.’” Women’s Art Journal (Spring-Summer 2007): 29–36.

Victoria Chandler

Historic Arkansas Museum

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Arkansas State Building

Arkansas State Building  Caroline Shawk Brooks

Caroline Shawk Brooks  Butter Sculpture

Butter Sculpture  Dreaming Iolanthe

Dreaming Iolanthe  Dreaming Iolanthe Butter Sculpture

Dreaming Iolanthe Butter Sculpture

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.