calsfoundation@cals.org

Mass Media

For a small state with regard to population and geography, Arkansas has a surprisingly large number of mass media: including 103 newspapers, 207 commercial radio stations, seventeen commercial television stations, and dozens of magazines and other publications as of 2023. In addition, there are eleven non-commercial television stations, seventy-two non-commercial radio stations, and twenty-six cable television networks, according to the Arkansas Media Directory.

Mass media in Arkansas developed much like they did throughout the country. That is, they appeared where and when population and business development supported them. Two key elements determine the success of any of the mass media (newspapers, magazines, radio, television, and cable): revenue, in the form of advertising and purchases (subscriptions and single copy sales); and audience, in the form of readers, viewers, and listeners.

Arkansas was relatively slow to develop, even after it became a state. For most of its history, it has been characterized as “small, rural, and poor.” These elements directly affected how media developed in Arkansas. Well into the twentieth century, Arkansas was still a state of small communities. In each of its seventy-five counties, county seats attracted people and businesses. In some counties, in fact, two county seats were designated due to large distances across counties. In 2006, ten Arkansas counties still had two county seats and—to underscore the importance of having that status—eighteen such county seats still supported newspapers, and sixteen of the twenty had radio stations. By 2023, the number of newspapers in these county seats had fallen to fifteen, with eighteen of the cities now supporting at least one radio station.

The Early Years

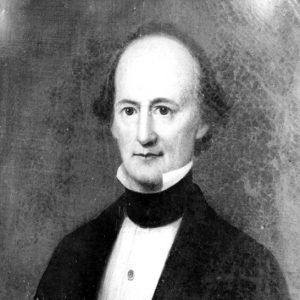

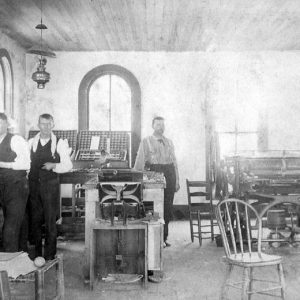

The first newspaper in the state was the Arkansas Gazette, founded in 1819, nearly seventeen years before Arkansas became a state. Its legendary publisher and editor, William Edward Woodruff, was born in New York in 1795. Looking west for adventure and opportunity, Woodruff was working for a newspaper in Nashville, Tennessee, when he heard that a man had abandoned his plan to start a newspaper in the Arkansas Territory. That was the opportunity Woodruff was looking for. He bought a second-hand Ramage press and necessary supplies on credit in St. Louis, Missouri, and set out for Arkansas. Using a variety of waterways, he arrived at the territorial capital, Arkansas Post, on October 31, 1819, and produced his first issue less than three weeks later, on November 20, 1819. He was the entire staff: editor, publisher, foreman, compositor, pressman, printer’s devil, and mail clerk.

When the territorial legislature voted to move the seat of government to Little Rock (Pulaski County), a more central location, in October 1820, Woodruff followed with his newspaper. His first Little Rock issue was dated December 29, 1821, a little more than two years after he had created the Gazette.

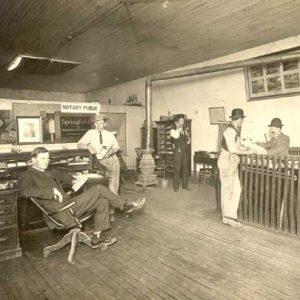

Early problems for the territory-wide newspaper included shortages of both paper and news, as well as challenges of getting the newspaper delivered to subscribers. The poor mail delivery and poor roads compounded delivery problems. Related to distribution problems was the difficulty in getting “subscribers” to pay. This problem plagued most newspapers for years to come. Newspapers had to look to other sources of revenue, including job printing and publishing legal notices. It also was common practice for readers to offer, and for newspapers to accept, goods such as chickens, a sack of flour, or a side of beef as payment for subscriptions.

For many years, one of the major benefits of publishing a newspaper was that of being designated the official—and often the only—printer in an area. That meant additional revenue from job printing, as well as from government sources, such as the printing of public notices. Thus, newspapers and politics were strange bedfellows, which led to many tense and tenuous situations over the years. In fact, some newspapers were even started because of politics. When a politician did not like the political philosophy of a newspaper, he could start his own. For example, Robert Crittenden founded the Arkansas Advocate to oppose William Woodruff, leading to the first newspaper war in the state.

It was as much a printers’ war as a newspaper war, since newspapers were so wrapped up in legal and official printing. The newspapers tried about anything to be named the official printer, including bribes and aggressive bidding. A third newspaper, the Political Intelligencer (later changed to The Times), compounded the competition when it appeared in Little Rock in 1834. (The Arkansas Democrat was created in 1878 also to oppose the Gazette.)

By the time Arkansas entered the Union in 1836, there were only four newspapers in the state—the three Little Rock newspapers and the Arkansas State Democrat (later changed to the Southern Sentinel) in Helena (Phillips County). Even though the Sentinel only lasted until 1841, Helena continued to be an active newspaper town for many years due, in part, to its strategic location on the Mississippi River. By 1860, Arkansas had three dozen weeklies but no dailies.

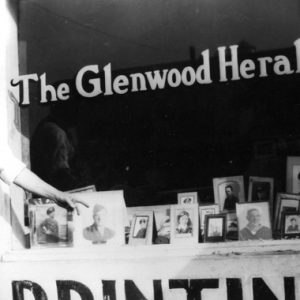

Numerous newspapers came and went in succeeding years. Throughout the state, newspapers followed the development of towns and cities, people, and businesses. Van Buren (Crawford County) claimed to have the nation’s farthest west newspaper, the Arkansas Intelligencer, started in 1842. The oldest weekly in the state still in existence is the Dardanelle Post-Dispatch, founded in 1854.

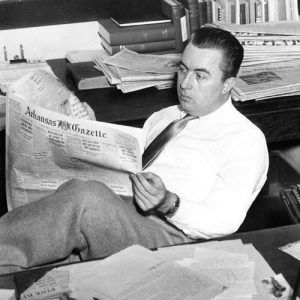

It is difficult to designate a specific year in which many of today’s newspapers started due to name changes, mergers, changes from weekly to daily frequency, and sales. For instance, today’s Arkansas Democrat-Gazette came about in 1991, when the Arkansas Gazette was shut down and the Arkansas Democrat bought its assets and changed its name. The Arkansas Gazette had been founded in 1819 and had gone through several name changes in the course of its life: The Arkansas Gazette (1828), Arkansas State Gazette (1836), Arkansas State Gazette and Democrat (1850), Arkansas State Gazette (1859), Little Rock Daily Gazette—the first daily in the state (1865)—and back to the Arkansas Gazette in 1870, a name it kept until 1991.

As for the Arkansas Democrat, it was built on the ruins of the Evening Star in 1878 and never changed its name but did go through many owners, including being acquired by the business manager of the Gazette in 1909. Purchased by WEHCO IN 1974, Walter Hussman Jr., worked to make the Arkansas Democrat a true competitor to the Arkansas Gazette. Over the course of almost two decades, Hussman made major changes to his paper, including offering free classified ads and moving to morning publication from the previously published afternoon edition. He also hired John Robert Starr as editor to lead the publication during the newspaper war. These changes led to the sale of the Arkansas Gazette to the Gannett Company in 1986. Unable to counter the gains made by the Arkansas Democrat, the Gannett Company eventually closed the Arkansas Gazette. After buying the assets of the Arkansas Gazette from the Gannett Company on October 18, 1991, the Arkansas Democrat changed its name to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and boasted “The Best of Both.” The new publication claimed the history of the Arkansas Gazette as its own.

As expected, the newspaper industry had many “firsts” in the nineteenth century. The first “extra” was printed by the Arkansas Gazette on February 22, 1820, about an address to Congress by President James Madison. The first female editor of a daily newspaper in Arkansas was Louise Payne, at the Fayetteville Democrat, in 1893. The first of several newspapers with the name Arkansas Traveler (now the name of the University of Arkansas student newspaper) was the one that appeared in Arkadelphia (Clark County) in the mid-1850s, edited by Sam M. Scott.

The newspaper format—either broadsheet (full-size) or tabloid—has also been used for special interest organizations and industries. Churches and denominations have regularly used newspapers to communicate with their members. One of the first religious newspapers in the state was the Ouachita Conference Journal in the 1850s, published by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The first foreign language newspaper in Arkansas was the Staats Zeitung, published in 1866, in Little Rock, indicating the growing German population in the state.

The Civil War brought hard times for newspapers in Arkansas. In Little Rock, the two newspapers, the True Democrat and the Gazette, both ran out of paper and suspended publication at times. Neither was being printed when Federal troops occupied the capital in early September 1863. However, John R. Eakin kept the Washington Telegraph in Hempstead County going throughout the war. He has been called a “Confederate propagandist,” but he refused to print stories he knew were false. Several Federal newspapers popped up. If Union soldiers found a press and some paper, they promptly printed a newspaper. By 1864, Unionist newspapers appeared in Little Rock and Fort Smith (Sebastian County), such as the New Era in Fort Smith, the Unconditional Union in Little Rock, and the National Democrat in Little Rock.

In 1854, the first state-related magazine appeared—Arkansas Magazine. It was a monthly and seemed to be popular, but it did not last long. Other magazines and journals followed, but they were few and far between, and none survived for very long.

Reconstruction

Following the Civil War, the rapid development of the telegraph and railroads linked not only all corners of the state but also the state with the rest of the nation. Now news was more plentiful, was fresher, and could be sent to readers more quickly. Roads were developed and improved. County fairs sprung up, giving a much-needed new source of advertising revenue to local newspapers.

Community newspapers were the lifeblood of their towns and counties. They provided a public diary of the community for all to read. Local institutions—retailers, schools, businesses, governments, and churches—all depended on newspapers to tell citizens what was going on and how to be informed and involved. People also depended on their local newspapers to provide them news from the state, region, and country. Some such news came via telegraph. Much came from exchange copies of other newspapers.

Problems continued for newspapers: subscribers who failed to pay; a weak economy (such as the Panic of 1873); and a dependence on a questionable product—patent medicine—for advertising revenue. But newspaper numbers grew as did cities and towns. By 1870, there were fifty-six newspapers in the state, both monthlies and weeklies; by 1885, there were ten dailies and 147 weeklies.

On October 15, 1873, a meeting of newspaper publishers in Little Rock started the Arkansas Press Association (APA), the statewide trade association of newspapers, after several earlier efforts had failed. This group allowed newspapers to pool their resources and influence to foster growth and stability of the newspaper industry. The APA and its members generally led the local and state march of progress, spreading news and literacy through issue advocacy, including economic development and agricultural diversification.

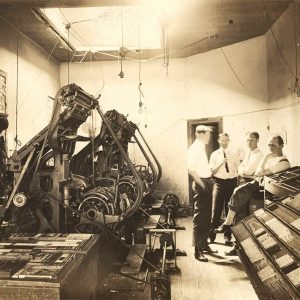

In the late nineteenth century, typesetting machines were introduced to Arkansas, following the invention of the Linotype machine in 1886 and the subsequent appearance of other brands. In 1895, Louie D. Freeman bought one of the early machines—probably the first by a weekly in the state—and brought it to Harrisburg (Poinsett County), where he established the Modern News. The White River Current in Des Arc (Prairie County) continued to set type by hand into the 1950s. By the mid-1970s, handset type was gone in Arkansas newspapers.

By 1899, there were 256 assorted publications being printed in Arkansas, and by 1909, this had increased to 315. The maturing city press boasted of modernized printing equipment, an independence of the press from politics, and a more sophisticated coverage of the news, including more and more professional reporters. On November 20, 1906, the Arkansas Gazette became a seven-days-a-week publication. Two years later, they introduced color comics to their Sunday readers.

Notable People in Newspapers

The newspaper industry in Arkansas gave fame to numerous people during the nineteenth century. Opie Read was a well-known reporter before he began editing a comic weekly called the Arkansaw Traveler. He then became a nationally famous novelist, often using Arkansas for his settings. William Minor Quesenbury was Arkansas’s most beloved editor and writer. During the 1850s, his South-West Independent of Fayetteville (Washington County) was full of good humor and often illustrated with his own woodcuts and poetry. Another highly regarded editor was Albert Pike, later a famous lawyer and Confederate general. Pike promoted Masonry and tomatoes and opposed lynchings in his Arkansas Advocate. Christopher Columbus Danley’s fame at the Arkansas State Gazette came from his heroic opposition to secession.

The Twentieth Century

Magazines, especially literary magazines, appeared from several quarters during the twentieth century. While not as plentiful as newspapers, they still made their mark on Arkansas literary history. The best-known magazine was the Little Rock Sketch Book, “A high-class pictorial and literary magazine of the early 20th Century,” edited by Julia “Bernie” Babcock, the founder of the Arkansas Museum of Natural History and Antiquities (later renamed the Museum of Discovery) in Little Rock. The Arkansaw Traveler by Opie Read became so popular that he moved it to Chicago in order to utilize better mailing connections. The Arkansas Thomas Cat by Jefferson David Orear of Hot Springs (Garland County) was full of humor, often at the expense of the pompous and self-satisfied.

With a strong agriculture base, as well as an increasing interest in education, magazines appeared in Arkansas supporting these as well as other disciplines. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission in 1924 issued its first magazine, titled The Arkansas Deer. By the second issue, it had become The Arkansas Conservationist. Today, it is called Arkansas Wildlife. Trade associations, notably in medicine, education, and banking, also produced specialized publications.

The new century brought maturing newspapers and newspaper companies. Multiple newspaper ownerships were called chains (or groups if they included other media). One of the first chain owners was Clyde E. Palmer, who bought newspapers in Texarkana (Miller County), El Dorado (Union County), Camden (Ouachita County), Hope (Hempstead County), and Hot Springs, and had interests in other newspapers in Stuttgart (Arkansas County), Magnolia (Columbia County), Stephens (Ouachita County), and Russellville (Pope County). After Palmer’s death, his chain of newspapers were acquired by his son-in-law, Walter E. Hussman Sr. The company was renamed to relflect Hussman’s ownership and became known as WEHCO Media, Inc., an acronym for Walter E. Hussman Company. Other newspaper chains followed, most notably those owned by Donald W. Reynolds (Donrey Media).

While most newspapers focused on supporting communities in the state, some publications were created to deliver particular political and social messages. Anti-Catholic sentiment in the state led to the publication of the Liberator from 1912 to 1915. At least one newspaper related to the Ku Klux Klan operated in Arkansas in the 1920s. The Arkansas Traveller, printed in Little Rock, appeared in 1923 and 1924. A KKK opposition paper operated at the same time in Marshall (Searcy County), the Eagle. Published between 1923 and 1929, the weekly ceased publication after the influence of the KKK decreased.

From the end of the nineteenth century through the first two decades of the twentieth century, newspapers owned a monopoly on the news business, including politics, culture, society, entertainment, and sports. But lurking in the shadows was new competition for newspapers—radio.

Radio Enters the Marketplace

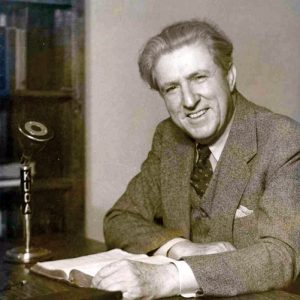

The first radio station in Arkansas went on the air on February 18, 1922, according to Ray Poindexter in Arkansas Airwaves. Harvey C. Couch Sr., an industrialist and founder of Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L, now Entergy Arkansas), had visited pioneer radio station KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1921. Couch arranged for a radio demonstration in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in November of that year to the local Rotary Club. By February 1922, Couch built an antenna and named his new baby WOK (for “Workers of Kilowatts”). There were no commercials on the station; instead, it was fully supported by the utility company. In coming months, the station had many firsts in Arkansas: first broadcast sermon, first broadcast sports event, first broadcast music concert, first remote church broadcast, and more. The first preacher to make good use of radio was Brother Ben Bogard of Little Rock, the fiery Missionary Baptist opponent of “Darwinism” and evolution. His radio show helped promote Initiated Act 1, which outlawed the teaching of evolution.

The first radio station in Little Rock was WSV, its first broadcast being on April 8, 1922. That same year, a number of radio stations joined to broadcast sports and speeches. That cooperative arrangement was the forerunner of today’s state and regional networks. On June 26, 1922, the Southwest American in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) was granted a license for KGAR. This was the first Arkansas newspaper to start a broadcasting station. Most early radio stations were owned by retailers or manufacturers, such as Moore Motor Company in Newark (Independence County). Another newspaper that owned a radio station was the Courier-News in Blytheville (Mississippi County).

As other radio stations went on the air, there was a need for more than just local news, weather, and sports. Stations turned to more regional sports events, on-site promotional broadcasts, and even national sports events, such as the blow-by-blow broadcast of a heavyweight prize fight in 1923. Local radio stations also looked nationally to other radio stations for programs to broadcast locally. Arkansas was the site for its own popular two-man radio show, Lum and Abner, sponsored by Quaker Oats. The show signed on with NBC. The “Jot ’em Down Store” in the fictional Pine Ridge, run by characters Lum Eddards and Abner Peabody, became so famous that in April 1936, the town of Waters (Montgomery County) changed its name to Pine Ridge—the fictional town in the radio series. A museum about the show opened in 1972.

Two years before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began his famous “fireside chats,” the same format was used on radio station KTHS in Hot Springs. Bill Shepherd of AP&L in Pine Bluff made weekly talks called “A Fireside Chat on Safety.” Farm news was important, and Ardis Tyson’s columns were read by Bob Buice over station KARK. Since many farm families came home to eat dinner at noon, this became an important hour for radio. The King Biscuit Time program from KFFA in Helena featured Sonny Boy Williamson, whose picture then appeared on the company’s flour sacks.

Little Rock’s first continuous radio station, KLRA, began as WLBN in Fort Smith in June 1927. Its owner moved the station to Little Rock in October of that year and changed the call letters to KLRA in 1928. Its slogan was “Voice of the Wonder State.” It joined the CBS network in 1929. The station had a staff band and did remote broadcasts from such sites as a baseball park and the Little Rock Zoo.

Radio stations experienced considerable problems during World War II. Advertising declined drastically since there was not much merchandise to sell. Jack Parrish, manager of KOTN in Pine Bluff at the time, said that his station lost eighty percent of its revenue during the first six weeks following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The military draft and enlistments siphoned off personnel. Some, such as Al Shirley at KARK, enlisted in the U.S. Marines immediately after Pearl Harbor. Wages were frozen by the federal government. Women moved in to replace men, such as Veda Beard at KBTM in Paragould (Greene County), who was issued a power of attorney by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to act as a station licensee in the absence of the assignee.

Radio played an important role in the war effort, helping with drives for scrap metal and rubber, selling war bonds, and boosting morale of everyone, military and civilians alike. KOTN assisted the Pine Bluff Jaycees in their collection of aluminum. KBTM carried musical shows from the Strand Theater in Jonesboro (Craighead County) to boost morale. In 1941, the FCC established a monitoring station in Sylvan Hills (Pulaski County) to listen for distress calls from ships and airplanes that had lost contact with their bases as well as from ships that were under attack.

Following the war, broadcasting grew rapidly as veterans came home. In 1947, the oldest AM radio station in Arkansas still in existence—KUOA in Siloam Springs (Benton County), founded in 1926—became the first to add an FM station. The Arkansas Broadcasters Association was formed in 1948 to represent radio interests and later added television as that industry developed. In 1950, KNEA in Jonesboro established “format programming,” which became the standard for radio stations in the state in coming years. The station broadcast the Hit Parade songs all day long, a new concept at the time.

Arkansas radio was credited with electing a governor in 1952. Francis Cherry, a little-known chancery judge from Jonesboro, used a radio “talk-a-thon” approach as his method of campaigning. On July 2, 1952, he talked for twenty-four and a half hours straight. Subsequent broadcasts—none as long as that one—originated in various cities throughout the state and were broadcast on a statewide network. This method worked because few people had television sets.

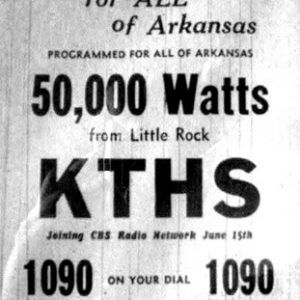

In 1953, after more than thirty years of radio in Arkansas, the state finally got its first 50,000-watt station. KTHS went on the air in Hot Springs and began broadcasting at the higher power, which allowed its signal to be carried throughout the state and region. During the 1960s, many AM radio stations added FM stations. Today, there are more FM stations than AM stations in the state.

West Memphis (Crittenden County) radio station KWEM operated from 1947 to 1960, providing early exposure for future musical legends such as B. B. King, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Sonny Boy Williamson, and Howlin’ Wolf. After a half century of silence, the station was revived in an online format in the twenty-first century. The community radio station KABF, which calls itself “the voice of the people” has broadcast since the mid-1980s from Little Rock to central Arkansas listeners.

The idea of a statewide radio news network was put forth by KARK manager Ted Snider in 1967. The network started that June with nineteen stations. In February 1972, Snider purchased KARK AM and FM, as well as ARN (Arkansas Radio Network). KARK-TV was purchased by Combined Communications, and since now two different companies owned the KARK name, KARK radio, which it had been named for forty years, changed its name to KARN.

Television Arrives in Arkansas

Television came to Arkansas on April 5, 1953, when KRTV, a UHF station in Little Rock, made its debut. Announcer Bob Lawrence is thought to have been the first person seen on an Arkansas television station. The first VHF station in the state was KARK in Little Rock, licensed on April 15, 1954. It has been affiliated with NBC since it began. VHF (very high frequency) signals carried farther than UHF (ultra high frequency), which also required a special antenna at first.

As with other media, television followed the people, first in larger cities, and gradually finding demand in smaller communities. Cable and satellite dishes eliminated the problems of signals not reaching people in mountainous and rural locations. Powerful signals from big cities crisscrossed the relatively small state, soon giving statewide coverage for major advertisers, politicians running for statewide offices, and others. The first politician to use television almost exclusively in campaigning was Dale Bumpers in his campaign for governor in 1970.

Television—with its decided advantage of sight, sound, motion, and color—gradually became the medium of choice for most Arkansans. More people spend more time watching television than with any other medium, especially with the widespread availability of cable television in the 1990s.

CATV first appeared in 1949 in a small community in Pennsylvania. An appliance dealer got the idea of bringing television signals to his rural community via a cable instead of the traditional over-the-air route. The first cable system appeared in Arkansas in October 1948 in Tuckerman (Jackson County), one of the first in the country. There was enough cable activity in the state over the next two decades that the Arkansas Cable Telecommunications Association was founded in 1972. Cable television has expanded the numbers of channels available to viewers tremendously. There are pay channels (HBO, Showtime, Cinemax, The Movie Channel); special interest channels (golf, travel, history, food, cartoon, speed, comedy, etc.); and superstations (Atlanta, Chicago, CNN), which are seen throughout the country.

In 1959, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 359, which created a nine-member commission to study the feasibility of educational television in the state. As a result, and “after an enormous amount of study, planning, legislating and fund-raising,” according to Arkansas Airways, KETS, Channel 2, went on the air on December 4, 1966, in Conway (Faulkner County). The Arkansas Educational Television Network (AETN) in Conway began operating KETS, as well as four other stations in Mountain View (Stone County), Arkadelphia, Fayetteville, and Jonesboro; AETN later became Arkansas PBS in 2020. By 2006, six non-commercial television stations were broadcasting in Arkansas, supported by five translator stations that help cover remote and isolated portions of the state.

The Minority Press

The Arkansas State Press, best known of the few Black newspapers in Arkansas history, played a major role in the Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis of 1957. L. C. and Daisy Bates started the newspaper in 1941. They kept the newspaper going as long as they could, but it closed in 1959. Daisy Bates revived it in 1983 and sold it to Janis Kearney in 1988. The newspaper struggled for another decade and closed again in 1998. Apparently, the Black population in Arkansas had been integrated into newspapers to the point of making a Black-only newspaper largely unnecessary. The monthly Arkansas Tribune was, for a while, the only Black newspaper known to be still publishing in Arkansas, even if only sporadically.

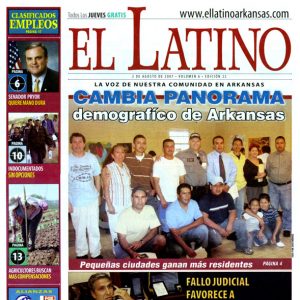

On the other hand, the Hispanic population in Arkansas grew rapidly in the 1990s, prompting the introduction of at least four Hispanic-focused newspapers produced in Arkansas: El Latino in Little Rock, Hola! Arkansas in Little Rock, La Voz deArkansas in Little Rock, and La Prensa Del Noroeste De Arkansas in Springdale (Washington and Benton counties).

Twenty-first Century

At the end of 2010, Arkansas had at least one newspaper in each of its seventy-five counties. There were twenty-eight daily newspapers, six semi-weekly newspapers and ninety-nine weekly newspapers—133 paid circulation newspapers in all. Of these, thirty-seven were single ownerships; all others are owned by newspaper or media chains. The largest owner of Arkansas newspapers in 2010 was the Stephens Media Group of Las Vegas, Nevada, with twenty papers. Others are WEHCO Media/Palmer Newspapers of Little Rock (sixteen); Rust Communications of Cape Girardeau, Missouri (ten); Liberty Group of Northbrook, Illinois (eight); Lancaster Management of Gadsden, Alabama (six); and Paxton Media Group of Paducah, Kentucky (five). Five cities in Arkansas had two or more competing newspapers: Little Rock, Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Nashville (Howard County), Star City (Lincoln County), and White Hall (Jefferson County).

By 2023, the number of newspapers in the state had dropped precipitously. Only eighteen dailies continued operation, with eight-four weeklies and five semi weeklies. Closure and consolidation led to the discontinuation of many of the newspapers.

In addition to paid circulation newspapers, there have been at times a number of free circulation newspapers, such as the Arkansas Times, Little Rock Free Press, and Nightflying. Too, there are numerous free publications throughout the state, including shoppers, auto-buyer guides, and many real estate tabloids and magazines.

As for broadcasting, from the 1930s, the airwaves were deemed to belong to the public, and public service was mandated by law. However, deregulation in 1997 led to the rise of chain ownership. Often, local news disappeared, and stations could get by with almost no employees. One consequence of this was that, in local emergencies, the local station was not a source of information.

By 2010, 199 FM radio stations and eighty-six AM stations broadcasted in Arkansas. Many were owned by chains and groups. Those owning five or more Arkansas radio stations, and their headquarters, include: East Arkansas of Wynne (Cross County); Bunyard of De Queen (Sevier County); Citadel of Las Vegas; Clear Channel of San Antonio, Texas; Crain of Searcy (White County); Equity of Little Rock; Max Media of Virginia Beach, Virginia; Noalmark of El Dorado; Saga of Gross Pointe Farms, Michigan; Sudbury of Blytheville; and WRD of Batesville (Independence County). By 2023, the number of AM stations had decreased to seventy-seven, with 177 commercial FM stations in operation.

There are more than one million television households in modern-day Arkansas. There are seventeen commercial television stations in the state. Those groups include Sinclair, Gray, Tegna, and Mission. It is not surprising that most of the television stations are located in the largest population centers of the state: Little Rock, Fort Smith, Fayetteville, Jonesboro, Rogers (Benton County), and Hot Springs.

By 2010, most municipalities in Arkansas could receive cable television. According to the Arkansas Cable Telecommunications Association, twenty-six operators of cable systems range from a few small, family operations to multi-system operators. They provided cable services to more than 600,000 cable households. The largest operators included: Cox Communications, Comcast, WEHCO Video, Charter Communications, and Cebridge Connections. The Paragould and Conway cable systems are municipally owned.

Radio stations serving both African Americans and Latinos in the state broadcast a variety of programs, including both music and religious services. Stations in Hope, De Queen, and Little Rock, as well as in other cities in the state, broadcast in Spanish and offer a connection for the thousands of Arkansans who do not speak English as a first language. Several stations in the state offer a Regional Mexican Music format, including stations in Lonoke, Fayetteville, and Bentonville. Stations aimed at the African American community are heard across Arkansas, with listeners in Texarkana, El Dorado, Little Rock, Helena-West Helena, and other cities able to hear these broadcasts. Programming includes various types of music, including hip-hop and gospel, as well as news and local shows.

Spanish language television operates in several markets in the state, with stations in Little Rock and Bentonville operating as part of the Univision and Telemundo networks. Several sub-channels aimed at African Americans are also available, including Bounce and Soul of the South.

Magazines in Arkansas have evolved into specialized niche publications, some still in traditional slick magazine format, but others in tabloid-size publications on newsprint. Still others might better be classified as journals or even elaborate newsletters.

The state’s small total population and few metropolitan areas have pushed publishers out of mass appeal publications to focus on smaller, more clearly defined audiences. Among the categories of magazines and other publications are: agriculture (Arkansas Agricultural, Arkansas Cattle Business, Front Porch); religious (Arkansas Baptist Newsmagazine, Arkansas Catholic, Arkansas Episcopalian, Arkansas United Methodist, Baptist Trumpet, The Spirit Magazine); health (Arkansas Health & Living, Arkansas Hospitals, Arkansas Medical News, Heritage Health Magazine, Journal of the Arkansas Medical Society); military (Arkansas Minuteman, The Drop Zone, Arsenal Sentinel); families (Little Rock Family, Little Rock Baby, Parenting in Arkansas); professional (Arkansas Banker, The Arkansas Lawyer, Arkansas Educator); city and regional (Little Rock Monthly, Celebrate Northwest Arkansas, Searcy Living); society (Soiree, Inviting Arkansas, Jonesboro Occasions); and lifestyle (AY, Arkansas Life).

On many college and university campuses in Arkansas, media play an important role in fostering communication among students, faculty, staff members, and even the communities in which they are located. On most campuses, the media are affiliated with the institutions themselves, usually run by students under a faculty member’s supervision. These range from student newspapers to university radio stations and even some cable access stations.

The 2006 Arkansas Media Directory listed twenty-nine non-commercial radio stations owned and run by colleges, universities, school districts, and churches. The 2023 edition included seventy-two non-commercial stations, although many are simply repeaters of various religious networks. The ten non-commercial television stations include, in addition to the six AETN stations and five translator stations, KASU-TV of Jonesboro (Arkansas State University); MTV-TV of Little Rock (Little Rock School District); UALR-TV of Little Rock (University of Arkansas at Little Rock); KLEP-TV of Newark in Independence County (Newark Schools); KCIB-TV of El Dorado; KEMV-TV of Mountain View; and Arkansas Tech-TV of Russellville (Arkansas Tech University).

Online publications offer consumers easy access to breaking news events. The Arkansas Blog, created and hosted by the Arkansas Times and operated for many years by editor Max Brantley, allows readers real time updates to important stories. Various newspapers, television stations, and radio stations offer news through websites and have been joined by online only media outlets. Examples include the Arkadelphian, a publication focused on Arkadelphia and surrounding communities in Clark County. Other local news reporters rely on Facebook, Substack, X (formerly Twitter), and other platforms to serve their communities as citizen journalists.

Media will continue to grow and change in Arkansas, and elsewhere, as technology changes and develops. It is probable that there will be more media, but more targeted media, more personal media, and more media-on-demand. A host of new ways to send and receive information will lead to a corresponding decrease in the mass media we know today.

For additional information:

2023 Arkansas Media Directory. Little Rock: Arkansas Press Association, 2023.

Allsopp, Frederick W. History of the Arkansas Press for a Hundred Years and More. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Publishing Co., 1922

———. Little Adventures in Newspaperdom. Little Rock: Arkansas Writer Publishing Company, 1922.

Arkansas Cable Telecommunications Association. http://www.arcta.org/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

Arkansas Democrat Project. Archives of the Davis and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Online at http://pryorcenter.uark.edu/project.php?projectFolder=Arkansas%20Democrat&thisProject=1&projectdisplayName=Arkansas

%20Democrat%20Project (accessed July 28, 2023).

Arkansas Gazette Project. Archives of the David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Online at http://pryorcenter.uark.edu/project.php?projectFolder=Arkansas%20Gazette&thisProject=2&projectdisplayName=Arkansas

%20Gazette%20Project (accessed July 28, 2023).

Arkansas Press Association. http://www.arkansaspress.org/ (accessed July 28, 2023).

———. Proceedings of the Arkansas Press Association from its Organization in October, 1873. Little Rock: 1876.

Blinder, Alan. “Emerging from the Shadows Cast across a River.” New York Times, June 1, 2014, p. 10A. Online at http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/02/us/kwem-return-has-west-memphis-reliving-its-role-in-radio-history.html?_r=0 (accessed July 28, 2023).

Condray, Kathleen. “Arkansas’s Bloody German Language Newspaper War of 1892.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Winter 2015): 327–351.

———. Das Arkansas Echo: A Year in the Life of Germans in the Nineteenth-Century South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Dawson, Teresa. “History of the Times Dispatch of Walnut Ridge, 1910–1980.” Lawrence County Historical Quarterly 4 (Fall 1981): 5–9.

Dougan, Michael B. Community Diaries: Arkansas Newspapering, 1819–2002. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

———. “The Little Rock Press Goes to War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 28 (Spring 1969): 14–27.

Fletcher, Read. “History of the Press of Pine Bluff.” Jefferson County Historical Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1979): 36–40.

Funk, Erwin. 64 Years of Newspapering in Arkansas, 1896–1960. Fayetteville, AR: 1960.

———. “Final Installment of Benton County Newspaper History.” Benton County Pioneer 4 (March 1959): 25–29.

Meriwether, Robert W. A Chronicle of Arkansas Newspapers Published Since 1922. Little Rock: Arkansas Press Association, 1974.

Ogilvie, Craig. “Izard County Newspapers, 1873–1971.” Izard County Historian 2 (January 1971): 16–23.

Pauly, Roger. “Paris to Pearl in Print: Arkansas’s Experience of the March from the Armistice to the Second World War through the Newspaper Media.” In The War at Home: Perspectives on the Arkansas Experience during World War I, edited by Mark K. Christ. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Poindexter, Ray. Arkansas Airwaves. North Little Rock, AR: 1974. Online at https://www.worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/History/Arkansas-Airwaves-Poindexter-1974.pdf (accessed December 2, 2025).

Purvis, Hoyt, and Stanley Sharp. Voices of the Razorbacks: A History of Arkansas’s Iconic Sports Broadcasters. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2013.

Reed, Roy, ed. Looking Back at the Arkansas Gazette: An Oral History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Ross, Margaret. Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

———. “Retaliation against Arkansas Newspaper Editors During Reconstruction.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Summer 1972): 150–165.

Rothrock, Thomas. “A History of the Washington County Press.” Flashback 16 (February 1966): 1–15.

Schexnayder, Charlotte Tillar. Salty Old Editor: An Adventure in Ink. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2012.

Shipman, Marlin. “Forgotten Men and Media Celebrities: Arkansas Newspaper Coverage of Condemned Delta Defendants in the 1930s.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 31 (August 2000): 110–124.

Smith, Robert Freeman. “John R. Eakin: Confederate Propagandist.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Winter 1953): 316–326.

Terry, Bill. “The Democrat vs. The Gazette: Arkansas’ Newspaper War.” Arkansas Times 5 (May 1979): 30–32, 35–38, 40–43.

Thompson, John A. “An Ambition Achieved: J. N. Heiskell Becomes Editor of the Arkansas Gazette.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 156–166.

Troutt, Fred D. “History of the Jonesboro Sun.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 9 (Autumn 1971): 2–11.

Williams, Harry Lee. “Craighead County’s Fourth Estate.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 2 (Autumn 1964): 6–12.

C. Dennis Schick

North Little Rock, Arkansas

Revised 2024 by David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.