calsfoundation@cals.org

Howlin' Wolf (1910–1976)

aka: Chester Arthur Burnett

Chester Arthur Burnett, known as Howlin’ Wolf or Howling Wolf, was one of the most influential musicians of the post–World War II era. His electric blues guitar, backing his powerful, howling voice, helped shape rock and roll.

Chester Burnett was born on June 10, 1910, in White Station, Mississippi, four miles northeast of West Point, Mississippi, to Leon “Dock” Burnett, a sharecropper, and Gertrude Jones. His parents separated when he was one year old; his father moved to the Mississippi Delta to farm, and he and his mother moved to Monroe County, Mississippi, where she became an eccentric religious singer who performed and sold self-penned spirituals on the street.

Burnett got the nickname “Wolf” because his grandfather would scare the youngster by telling him that the wolf in the woods would get him if he misbehaved. The rest of the family would then call him “Wolf” and howl at him.

When he was still a child, Burnett’s mother sent him away to live with his uncle, who was particularly hard on him, whipping him with a bullwhip and making him eat separately from the rest of the family. At age thirteen, he ran away from home and moved to the Mississippi Delta. He eventually found his father and his father’s new family on a plantation near Ruleville, Mississippi, and he began working on the plantation.

While there, Charlie Patton, the most popular musician in the Delta, showed him a few chords on the guitar. In January 1928, Burnett’s father bought him a guitar, and he began to play regularly, eventually teaming with Patton, who taught him many tricks of showmanship.

Preferring the life of a blues musician to the harsh life of sharecropping, Burnett began wandering the delta regions of Mississippi and Arkansas, playing music anywhere he could make money. He was a giant of a man, standing over six feet three inches and weighing some 275 pounds, and he became well known in the region as a blues performer, not only for his showmanship but also for his large size and loud, howling voice.

In 1933, the Burnett family left Mississippi and moved to a large Arkansas plantation in Wilson (Mississippi County). In early 1934, they moved to the Nat Phillips Plantation on the St. Francis River approximately fifteen miles north of Parkin (Cross County). Despite his commitment to his music, Burnett faithfully returned each spring to plow his father’s land.

Burnett began traveling in Oklahoma and all over the south, but Arkansas remained his main stomping ground. He learned to play harmonica from blues legend Sonny Boy Williamson and added it to his performing arsenal. Along with Williamson, Burnett also performed in the 1930s alongside Robert Johnson, Son House, Johnny Shines, Willie Brown, and Robert Jr. Lockwood.

Burnett enlisted in the army, for which he was not well suited. After serving in the army, Burnett returned home to farm on the Phillips Plantation. Then he went to Penton, Mississippi, to farm for two years, farming by day and playing music by night. In Penton, he met Katie Mae Johnson, and they were married on May 3, 1947.

In 1948, Burnett moved to West Memphis (Crittenden County). He took a job in a factory there, but the area’s blues clubs were the real draw for him. West Memphis, then a town bustling with blues clubs and gambling, was at the forefront of the newly amplified blues music, and Burnett adapted quickly. He assembled a blues band in the area called the House Rockers and made a commitment to make music his career. While Muddy Waters was giving birth to electric blues in Chicago, Illinois, Burnett was doing the same thing in West Memphis.

Beginning in 1948, Burnett was performing on local radio station KWEM in West Memphis (he both produced and sold advertising for his program), where he attracted the attention of record producer Sam Phillips in Memphis, Tennessee. Phillips’s recordings of “Moanin’ At Midnight” and “How Many More Years” were leased to Chess Records and became a double-sided hit, making Billboard magazine’s R&B top ten.

In September 1951, Burnett signed with the Chess label, and the Chess brothers convinced him to move to Chicago in the winter of 1952. His wife refused to follow him, and their marriage, which had been rocky, ended. Upon arriving in Chicago, Burnett broke into the scene quickly and assembled a band in the West Memphis style. Among his band members was a young guitarist from West Memphis, Hubert Sumlin, who would stay with Burnett for the remainder of Burnett’s career.

In 1954, he recorded “Evil,” his biggest hit to that point, which landed on the Cash Box magazine Hot Chart. It was also the first of many tunes that Willie Dixon wrote for Burnett. As his audience grew, he toured more widely, and in 1955, he played New York’s Apollo Theater. That year he made Cash Box magazine’s list of the top twenty-five male R&B vocalists. By that time, only Muddy Waters rivaled his popularity in the blues arena.

In 1956, Burnett recorded his masterpiece work, “Smokestack Lightnin’.” The hit peaked at number eleven on both the Cash Box Hot Chart and Billboard’s R&B chart. Over the next five years, Burnett recorded many hits: “I Asked For Water,” “Who’s Been Talking,” “Sitting on Top of the World,” “Spoonful,” “Wang Dang Doodle,” “Back Door Man,” “Goin’ Down Slow,” “I Ain’t Superstitious,” and “Red Rooster.” In 1959, Burnett released his first album on Chess, Moaning in the Moonlight, which was followed in January 1962 by Howlin’ Wolf, sometimes referred to as the “Rocking Chair” album. Greil Marcus of Rolling Stone magazine called it “the finest of all Chicago blues albums.”

On March 14, 1964, Burnett married Lillie Handley Jones, who was from Alabama. She was a property owner and a smart money manager, and they settled in south Chicago. She would remain with him until his death.

Burnett’s later hits included “Tail Dragger” (1962); “Built for Comfort,” “300 Pounds of Heavenly Joy,” “Hidden Charms” (all in 1963); and “Love Me Darlin’” and “Killing Floor” (both in 1964).

In September 1964, he traveled to Europe as part of the 1964 American Folk Blues Festival, touring with such blues artists as Sonny Boy Williamson, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Willie Dixon, and Sleepy John Estes. “Smokestack Lightnin’” was a huge hit in Great Britain, and Burnett commanded headliner status on the tour.

Burnett garnered wider exposure through the folk movement and British Invasion remakes of his classic blues songs. In 1965, he appeared on the ABC TV show Shindig with the Rolling Stones, who had a number-one hit in England with “Red Rooster.” Over the next several years, he played the prestigious Newport Folk Festival, the Berkeley Folk Festival, and the Ann Arbor Blues Festival. In that period, he released the albums Real Folk Blues (1966) and More Real Folk Blues (1967). In 1968, he released Howlin’ Wolf, often referred to as the “electric” Howlin’ Wolf album.

Despite failing health, including a 1969 heart attack, high blood pressure, and kidney problems, Burnett continued to tour and record. In May 1970, he went to London, England, and recorded The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions with such British rock stars as Eric Clapton, Mick Jagger, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, Steve Winwood, Ringo Starr, and Ian Stewart. It became the only Howlin’ Wolf album to appear on the Billboard 200, spending fifteen weeks on the chart and peaking at number nineteen.

In early 1971, Burnett released the album Message to the Young, which was considered his “psychedelic” record, as well as the nadir of his recording career. In May 1971, Burnett had a second heart attack, and doctors discovered that his kidneys were failing. He began to get hemodialysis treatments and was ordered by doctors to stop performing. But he would not quit, and three months later, he was the opening night headliner at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

In early 1972, Burnett cut the live album Live and Cookin’ at Alice’s Revisited. In August 1972, he received an honorary doctorate from Chicago’s Columbia College. In August 1973, he recorded his final studio album, The Back Door Wolf. In 1975, he was nominated twice for a Grammy Award for Best Traditional or Ethnic Album for Back Door Wolf and London Revisited, a repackaging of the London sessions recorded by both him and Muddy Waters.

On January 7, 1976, Burnett was diagnosed with a brain tumor. He underwent surgery from which he never recovered. He was removed from life support and died on January 10, 1976. He is buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Chicago.

Burnett was elected to the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1980 and was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1991. In 1994, the great bluesman was honored on a U.S. postage stamp.

For additional information:

Cohodas, Nadine. Spinning Blues into Gold: The Chess Brothers and the Legendary Chess Records. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000.

George-Warren, Holly, and Patricia Romanowski. The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll. New York: Rolling Stone Press, 2001.

Guralnick, Peter. “Howlin’ Wolf: What Is the Soul of a Man?” Oxford American 75 (2011): 60–65.

Lott, Eric. “Back Door Man: Howlin’ Wolf and the Sound of Jim Crow.” American Quarterly 63 (September 2011): 697–710.

Marsh, Dave, and John Swenson, eds. The Rolling Stone Record Guide. New York: Random House/Rolling Stone Press, 1979.

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. https://www.rockhall.com/inductees/howlin-wolf (accessed July 11, 2023).

Segrest, James, and Mark Hoffman. Moaning at Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin’ Wolf. New York: Pantheon Books, 2004.

Bryan Rogers

North Little Rock, Arkansas

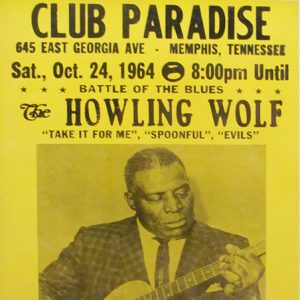

Howlin' Wolf Poster

Howlin' Wolf Poster  Howlin' Wolf Ad

Howlin' Wolf Ad  Howlin' Wolf

Howlin' Wolf  KWEM Automobile

KWEM Automobile  "Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"

"Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.