calsfoundation@cals.org

Johnny Cash (1932–2003)

aka: J. R. Cash

Johnny Cash was a world-renowned singer/songwriter of country music. With his deep, rich voice and often dark, often uplifting lyrics, he created a body of work that will be heard and remembered for generations to come.

J. R. Cash was born on February 26, 1932, in Kingsland (Cleveland County) to Ray and Carrie Cash. He had six siblings: Roy, Louise, Jack, Reba, Joanne, and Tommy. In 1935, the family moved to Dyess (Mississippi County), where they lived modestly and worked the land. The tragic death of Jack Cash in a 1944 sawmill accident haunted young J. R. for the remainder of his life. His mother introduced him to the guitar, and the local Church of God introduced him to music. He acquired a fascination for the guitar and a love for singing. Cash first sang on the radio at station KLCN in Blytheville (Mississippi County) while attending Dyess High School. Upon graduation in 1950, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force after a brief search for work in Michigan.

Cash was stationed in Germany, where he bought his first guitar for five dollars and formed his first band, the Landsberg Barbarians. After receiving an honorable discharge in 1954, Cash returned to San Antonio, Texas, where he married Vivian Liberto, whom he had met while in basic training four years earlier. The couple settled in Memphis, Tennessee, where Cash took radio broadcasting classes at Keegan’s School of Broadcasting and worked as an appliance salesman for the Home Equipment Company.

In Memphis, Cash met bass player Marshall Grant and guitarist Luther Perkins. They formed a band and soon were hired to perform once a week on Memphis radio station KWEM, which had recently moved from West Memphis (Crittenden County). In 1954, Cash and his band auditioned for Sam Phillips at Sun Records in Memphis. After several sessions, the trio recorded their first record, 78 rpm and 45 rpm, “Hey Porter” and “Cry, Cry, Cry” in 1955. It was Sam Phillips who gave Cash the name Johnny and labeled his band “Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two.” The release was successful and sold more than 100,000 copies. Cash toured feverishly, primarily through the tri-state area of Arkansas, Mississippi, and Tennessee—often with other Sun artists, such as Elvis Presley and Carl Perkins. When Sun Records released his second 78 rpm and 45 rpm record, “Folsom Prison Blues” and “So Doggone Lonesome” (1955), Cash was already a performing member on Shreveport’s weekly radio program, Louisiana Hayride. Around this time, Cash quit his job as a part-time appliance salesman and pursued his music full time. In mid-1956, Cash left Louisiana Hayride to perform on the Grand Ole Opry, but his stint on the Opry was short because Cash preferred not to appear in Nashville every Saturday night.

With his third release, “I Walk the Line” and “Get Rhythm” (1956), Cash established himself as a rising star. The recording peaked at No. 2 on the country charts and No. 19 on the pop charts. In 1957, Cash signed a lucrative recording contract with Columbia Records, taking effect the following year. At the end of 1957, Cash was the third-best-selling country artist in America and began appearing on national television programs such as The Jackie Gleason Show.

Sun Records continued to release Cash singles and albums until 1964, including his first No. 1 country single “Ballad of a Teenage Queen” (1958), just a few months before his Columbia record “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” (1958) reached the No. 1 spot. During the next decade, Columbia Records sold more than twenty million Cash albums worldwide.

Cash moved his family to California in 1961, which allowed him to pursue a limited acting career. He appeared on the television program Wagon Train (1959) and the movie Five Minutes to Live (1961). He continued acting throughout his career, appearing in a total of four theatrical movies, including A Gunfight (1971), as well as seven television movies.

The long tours and endless one-night gigs took a toll on many a performer, and in 1957, on a long road trip to Jacksonville, Florida, Cash began taking amphetamines to help stay awake. Members of his touring party were using them and were happy to share these “bennies” with Cash and his band. This was the start of an addiction that would plague Cash for the next decade. A bottle of 100 or so pills would cost less than ten dollars, and on the road, they were as important to Cash as his guitar.

During the 1960s, Cash maintained a hectic international touring schedule. His drug abuse increased, and his persona of the Man in Black took shape. In 1963 and 1964, Cash scored No. 1 country hits with “Ring of Fire” and “Understand Your Man,” respectively. Cash was releasing theme albums such as his acclaimed album titled Bitter Tears (1964), which recounted the plight of the American Indian. Cash was branching out of country music and finding a whole new “folk” audience. He performed at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, and it was around this time that Cash wrote a scathing letter to Billboard magazine blasting the country music establishment for ignoring his “new” music.

Cash’s drug abuse continued. While on stage at the Grand Ole Opry, he used a microphone stand to smash footlights along the front of the stage. Months later, he was arrested in El Paso, Texas, for illegally purchasing hundreds of pills in Juarez, Mexico. Two years later, when Cash was again arrested in Lafayette, Georgia, he realized he needed help. However, that same year, Cash attempted to kill himself by driving alone to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and getting himself lost in a series of dark caves. He felt so despondent over his drug addiction and broken promises that he wanted to disappear. However, once deep inside the caves, he became religiously inspired and realized he had much more to live for. He found his way out of the caves and, at that point, decided to seek help for his drug addiction and renew himself religiously. June Carter, who had toured with Cash since the early 1960s, was instrumental in breaking his addiction by constantly reassuring him and never giving up on him. In early 1968, Vivian Cash was granted a divorce from her husband, and Cash promptly married June Carter.

On February 4, 1968, Johnny Cash triumphantly returned to Arkansas for a special “Johnny Cash Homecoming Show” at the Dyess High School gymnasium. Later that year, long-time friend and guitarist Luther Perkins died. Arkansan Bob Wootton, born in the small town of Paris (Logan County), joined Cash’s band as a permanent replacement after literally coming out of the audience to play guitar during a concert in Fayetteville (Washington County) on September 17, 1968.

The year 1969 was a remarkable one for Cash. He was clean and sober, and he sold six and a half million albums. Cash toured the Far East; his album Johnny Cash at San Quentin went to No. 1 on the country and pop charts; he had two No. 1 country singles, “A Boy Named Sue” and “Daddy Sang Bass”; he recorded with Bob Dylan on Dylan’s Nashville Skyline album; and ABC launched The Johnny Cash Show, which was filmed at the Grand Ole Opry and aired in prime time through 1971. On April 10, 1969, Cash returned to Arkansas for a much-anticipated concert at Cummins Prison in Lincoln County.

Cash began the 1970s with another No. 1 country song, “Sunday Morning Coming Down” (1970). He would not have another country No. 1 hit until 1976, when Columbia Records released “One Piece at a Time.” Cash began spending time with his friend, evangelist Billy Graham, and in 1971 and 1972, he produced and filmed a movie in Israel about the life of Jesus Christ, titled Gospel Road (1973). Cash and Graham’s friendship grew over the next thirty years, and Cash often appeared at Billy Graham Crusades held around the world. One such appearance was in Little Rock (Pulaski County) at War Memorial Stadium in September 1989. In 1975, Cash published his autobiography, Man in Black, which sold more than one million copies. He briefly returned to television with The Johnny Cash Show as a 1976 summer replacement series and continued to tour the world throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1980, Cash became the youngest person ever elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame. A year later, Cash found himself in Stuttgart, Germany, at the same time as old friends Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis. They went on stage together and recorded a live album titled The Survivors (1982).

In the early 1980s, Cash had eye surgery, broke several ribs, and damaged a kneecap, all on separate occasions, and again became addicted to pills. He was hospitalized in 1983 with internal bleeding that almost killed him. Upon regaining strength, he checked into the Betty Ford Clinic and remained clean until his death.

In 1985, Cash joined several of his friends for a couple of albums. The Highwaymen reached No. 1 on the country charts and featured Cash with Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Kris Kristofferson. Later that year, Cash returned to Sun Records in Memphis to record the album Class of ’55 with Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison, and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Cash published his second book, Man in White, in 1986. It chronicled the life of Paul the Apostle. That same year, Cash was dropped from Columbia Records, and he signed with Mercury/Polygram Records, with which he recorded four albums: Johnny Cash is Coming to Town (1987), Water from the Wells of Home (1988), Boom Chicka Boom (1989), and The Mystery of Life (1991). In 1989, Cash was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

The second Highwaymen collection, titled Highwaymen II, was released in 1990. It peaked in the top five on the country charts. During the 1990s, Cash received recognition from many organizations: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (1992), the Kennedy Center Honors for Lifetime Contribution to American Culture (1996), the Arkansas Entertainers Hall of Fame (1996), and the Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement (2000)—one of numerous Grammy Awards he received.

In 1994, Cash signed an unlikely contract with rap producer Rick Rubin and American Recordings and released a successful album, American Recordings. Cash’s popularity soared. This release began a new series of acclaimed albums: Unchained (1996), American III: Solitary Man (2000), and American IV: The Man Comes Around (2002). These featured Cash recording songs written by such alternative rock performers as Soundgarden, Beck, and Nine Inch Nails. In March 2003, Country Music Television proclaimed Johnny Cash the “Greatest Man in Country Music.”

In 1997, Cash published a new version of his autobiography, titled Cash: The Autobiography. That same year, he announced he had been diagnosed with a rare form of Parkinson’s disease and was forced to give up touring. In 2001, the diagnosis was corrected when he learned he had autonomic neuropathy, which is not a disease but a group of symptoms affecting the central nervous system. Throughout the final years of his life, Cash was frequently admitted to the hospital, suffering primarily from various stages of pneumonia.

On May 15, 2003, June Carter Cash died of complications from heart surgery. Almost four months later, on September 12, 2003, Johnny Cash died at Baptist Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, from respiratory failure brought on by complications from diabetes—one of the many physical ailments Cash had been facing over the years. Johnny Cash is buried near his wife at Hendersonville Memory Gardens in Hendersonville, Tennessee.

The legend of Johnny Cash continues to inspire people around the world. In 2005, a major motion picture documenting the first half of his life, Walk the Line, was released and garnered both critical and commercial success. Several posthumous albums of Cash’s material have been released, including the “lost album” recorded in the early 1980s: Out Among the Stars (2014) on Columbia Records.

Tourists continue to visit Dyess to see the place that was home to Cash during his youth. In 2011, Arkansas State University in Jonesboro (Craighead County) purchased Cash’s boyhood home for a reported $100,000 and restored the house to serve as a museum; the Historic Dyess Colony: Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash opened to the public on August 16, 2014. In 2013, the United States Postal Service released a memorial stamp in honor of Cash.

In May 2016, plans for the first Johnny Cash Heritage Festival—set for October 2017—were announced. Cash’s daughter Rosanne Cash, who worked with Arkansas State University in planning the festival, said, “For the first time, we will hold a festival in Dyess, in the cotton fields surrounding my dad’s childhood home and in the town center of the colony. We foresee an annual festival that will include both world-renowned artists on the main stage and local musicians on smaller stages, as well as educational panels, exhibits and local crafts.”

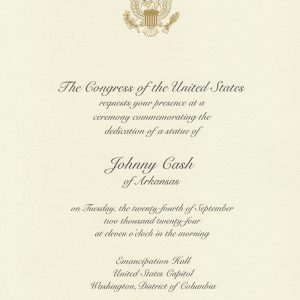

Act 810 of 2017 designated Highway 17 from Dyess to Wilson (Mississippi County) the Johnny Cash Memorial Highway. In 2019, the Arkansas General Assembly passed a law to replace the statues of Uriah M. Rose and James P. Clarke in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the U.S. Capitol with statues of Daisy Bates and Johnny Cash. In 2021, the Arkansas legislature approved designating February 26 (Cash’s birthday) as an annual “memorial day” honoring Cash. The day will be marked by an annual proclamation from the governor. Cash was the subject of the 2022 documentary Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon. In January 2024, U.S. Representative Bruce Westerman introduced legislation to name the post office in Kingsland after Cash; the measure passed the U.S. House of Representatives in June and the Senate in December, with the post office dedicated on June 7, 2025.

On June 28, 2024, eleven previously unreleased songs by Cash were released on an album titled Songwriter, which was co-produced by son John Carter Cash, featuring additional work by singer Vince Gill and the band the Black Keys. On September 24, 2024, the statue of Johnny Cash, created by sculptor Kevin Kresse of Little Rock (Pulaski County), was installed in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the U.S. Capitol, becoming the first musician thus honored.

For additional information:

Alexander, John M. The Man in Song: A Discographic Biography of Johnny Cash. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Banister, C. Eric. Johnny Cash FAQ: All That’s Left to Know about the Man in Black. Milwaukee: Backbeat Books, 2014.

Beck, Richard. Trains, Jesus, and Murder: The Gospel According to Johnny Cash. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2019.

Cash, John Carter. House of Cash: The Legacies of My Father, Johnny Cash. San Rafael, CA: Insight Editions, 2011.

Cash, Johnny. Cash: The Autobiography. San Francisco: Harper, 1997.

———. Man in Black. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1975.

“Dyess Gets Ready to Greet Singing Star Johnny Cash at His Homecoming Show.” Arkansas Gazette, February 2, 1968, p. 1.

Fairbanks, Brian. Willie, Waylon, and the Boys: How Nashville Outsiders Changed Country Music Forever. New York: Hachette Books, 2024.

Foley, Michael Stewart. “A Politics of Empathy: Johnny Cash, the Vietnam War, and the ‘Walking Contradiction’ Myth Dismantled.” Popular Music and Society 37 (July 2014): 338–359.

Edwards, Leigh H. Johnny Cash and the Paradox of American Identity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009.

Foley, Michael Stewart. Citizen Cash: The Political Life and Times of Johnny Cash. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

Harvey, Paul. Southern Religion in the World: Three Stories. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019.

Hawkins, Martin. Johnny Cash, The Sun Years. London: Charly Holdings, Inc., 1995.

Hilburn, Robert. Johnny Cash: The Life. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2013.

Hinds, Michael, and Jonathan Silverman. Johnny Cash International: How and Why Fans Love the Man in Black. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2020.

Historic Dyess Colony: Boyhood Home of Johnny Cash. http://dyesscash.astate.edu/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Johnny Cash Official Site. http://www.johnnycash.com (accessed July 6, 2023).

Laurie, Greg, with Marshall Terrill. Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon. Washington DC: Salem Books, 2019.

Light, Alan. Johnny Cash: The Life and Legacy of the Man in Black. Washington DC: Smithsonian Books, 2018.

Miller, Aaron W. “Cotton, Dirt, and Rising Water: Delta Geography in the Life and Work of Johnny Cash.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 50 (December 2019): 163–167.

Miller, Stephen. Million Dollar Quartet: Jerry Lee, Carl, Elvis & Johnny. London: Omnibus Press, 2013.

Moriarty, Frank. Johnny Cash. New York: MetroBooks, 1997.

Silverman, Jonathan. Nine Choices: Johnny Cash and American Culture. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010.

Streissguth, Michael. Johnny Cash: The Biography. New York: Da Capo Press, 2006.

———. “Making Sense of Johnny Cash in Dyess, Arkansas: Remarks Given at the Johnny Cash Heritage Festival, 2017.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 49 (August 2018): 84–89.

———. Ring of Fire: The Johnny Cash Reader. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003.

Tahmahkera, Dustin. “An Indian in a White Man’s Camp: Johnny Cash’s Indian Country Music.” American Quarterly 63 (September 2011): 591–617.

Thomas, Alex. “Cash Brings Down 1 More Curtain.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 25, 2024, pp. 1A, 5A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/sep/24/statue-of-johnny-cash-unveiled-in-the-nations-capitol/ (accessed September 25, 2024).

Tost, Tony. Johnny Cash’s American Recordings. New York: Continuum, 2011.

Warren, Robert Burke. Cash on Cash: Interviews and Encounters with Johnny Cash. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2022.

Willett, Edward. Johnny Cash: Fighting for the Underdog. New York: Enslow Publishing, 2018.

Woodward, Colin Edward. “At Cummins Prison: Johnny Cash and the Arkansas Penitentiary.” Pulaski County Historical Review 62 (Fall 2014): 85–92.

———. Country Boy: The Roots of Johnny Cash. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

———. “The Days before Dyess: Johnny Cash’s Early Arkansas Roots.” Pulaski County Historical Review 63 (Spring 2015): 10–29.

———. “‘There’s a Lot of Things That Need Changin’”: Johnny Cash, Winthrop Rockefeller, and Prison Reform in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Spring 2020): 40–58.

Eric Lensing

Memphis, Tennessee

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Music and Musicians

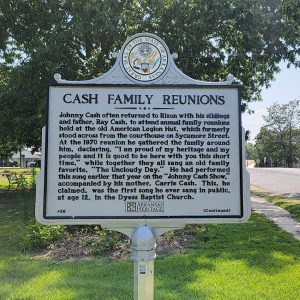

Music and Musicians Cash Family Reunions Memorial

Cash Family Reunions Memorial  Cash "William Overton" Memorial

Cash "William Overton" Memorial  Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash  Johnny Cash Boyhood Home

Johnny Cash Boyhood Home  Johnny Cash at Cummins

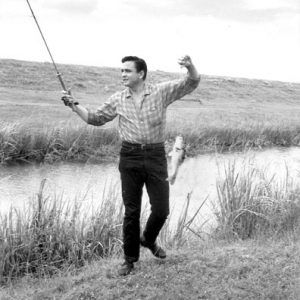

Johnny Cash at Cummins  Johnny Cash and Johnny Horton

Johnny Cash and Johnny Horton  Johnny Cash

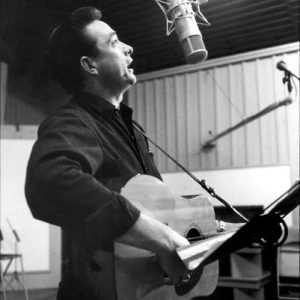

Johnny Cash  Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash  Johnny Cash Statue

Johnny Cash Statue  Johnny Cash Statue Invitation

Johnny Cash Statue Invitation  Dyess Colony

Dyess Colony  "Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash

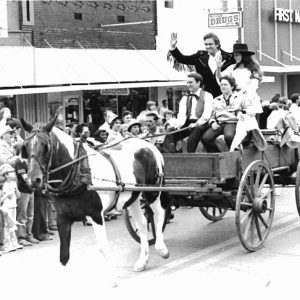

"Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash  Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade  Kingsland Johnny Cash Post Office Postcard

Kingsland Johnny Cash Post Office Postcard  Man in Black

Man in Black  Cash and Scaife

Cash and Scaife

Cash performed at Leavenworth Federal Prison in about 1970. The Feds did not permit the show to be filmed or recorded. There were still photos taken of this performance by the inmate staff photographer for the New Era Prison Magazine, published by the prisoners. After the show, Cash was given, on the QT, one of the rolls of film taken on that day.

Art Rachel #83546

Did you know that Johnny Cash published a science fiction story, titled “The Holografik Danser”? I didn’t.

From an article in the Nashville Scene:

“Rosanne also persuaded her father, Johnny Cash, and ex-husband, Rodney Crowell, to take part in the project, the Man in Black’s phonetically titled ‘The Holografik Danser’ being the only entry in the book that wasn’t drawn from a song. Written in 1953 while he was serving as an Air Force radio operator in Germany, Cash’s futuristic, at times gripping Cold War fable not only predates his recording career, it foreshadowed a handful of episodes of the Twilight Zone as well.”