calsfoundation@cals.org

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

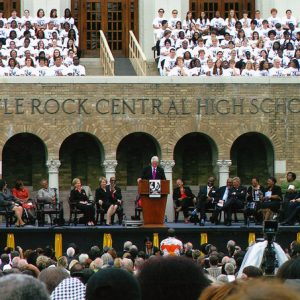

In November 2004, President George W. Bush joined former presidents George H. W. Bush and Jimmy Carter to speak at the dedication of the William Jefferson Clinton Presidential Center and Park in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton of New York introduced her husband, Bill Clinton, who explained that the library’s architecture symbolized the bridging of past and future. Few states had changed as dramatically as Arkansas in the modern era, but the persistence of rural cultural traditions and economic structures were celebrated by contemporary political leaders as proof of a distinctive Arkansas path.

State government had become more responsive and effective even as a one-party system of Democratic power remained intact until the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century. By the time Senator Clinton gained the Democratic Party’s nomination for president in 2016, the party’s dominance had dissolved. In 2016, a solid majority of Arkansans selected Donald Trump, the Republican candidate, over the state’s former first lady. In 2020, a majority of Arkansans again voted for Trump, although he did not win the presidency.

Reform Governors

When he took office in January 1967, Winthrop Rockefeller, the first Republican governor since Reconstruction, promised to dismantle the Old Guard regime of Orval Faubus, who had retired after twelve years as governor. The Rockefeller program included appointing trained professionals to restructured government agencies, raising taxes to support education, and upholding civil rights protections for African Americans.

Rockefeller’s aspirations exceeded his administration’s accomplishments. Even a politically adroit governor would have been hobbled by an antagonistic legislature controlled by the opposition party. Rockefeller, however, struggled to hash out deals while masking his contempt for lawmakers who demanded self-serving favors for votes.

The new governor did, however, exercise his executive authority to remedy endemic corruption that had flourished during the Faubus years. His appointments to agencies and commissions advanced professional oversight of public operations and businesses, particularly the insurance industry that had been convulsed by scandals arising from a “wild west” regulatory environment. He dispatched the Arkansas State Police to halt the illegal casino operations that had openly welcomed gamblers for decades to Hot Springs (Garland County). Rockefeller brought in a professional penologist, Thomas Murton, to end the brutality and torture documented in a state police report of the prison system. This impulsive reformer improved conditions, but his confrontations with numerous officials, including Rockefeller, sped his dismissal. The Arkansas General Assembly on this issue lined up with the governor to establish the Department of Corrections and enact several recommendations of a state penitentiary commission. The legislators did not, however, furnish adequate appropriations. In 1970, a federal judge, J. Smith Henley, found the prison system to be a “dark and evil world” and ruled it unconstitutional in the case Holt v. Sarver.

Rockefeller owed his office to African American voters, whose electoral clout was growing. The governor broke precedent in Arkansas and the South by appointing Black directors to several state executive offices. Alone among Southern governors, Rockefeller publicly memorialized civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. shortly after King’s assassination in 1968.

Rockefeller was not the first modern reform governor in Arkansas, although his efforts to base the state’s advancement on clean government and inclusive politics blazed a new trail. He believed a vigorous two-party system was a potent check on corruption. Yet his efforts to strengthen Republican competitiveness was hindered by skeptical conservatives within the party who believed Rockefeller’s liberalism hurt recruitment of white Southern voters. This faction gained the upper hand after Rockefeller lost the governorship.

In 1970, Dale Bumpers, a dark horse candidate for governor, defeated Faubus in the Democratic primary and Rockefeller in the general election. An improved relationship between the new governor and the legislature was due not only due to a shared partisan identification but also redistricting. Based on federal court standards for equitable representation, redistricting ushered into the General Assembly lawmakers who were younger, reformist, and obligated to urban constituencies. The 1971 session expanded public spending and services that more closely reflected responsibilities other state governments commonly met.

The Rockefeller agenda loomed large in legislative debates. Bumpers relied upon the previous administration’s blueprint to press for the reorganization of dozens of state agencies into thirteen cabinet departments with Act 38 of 1971. He also followed precedent by emphasizing education improvements but stunned lawmakers with a proposal to raise the income tax for the first time since the levy was established in 1929. The surge in revenues led to higher teacher salaries, the opening of public kindergarten classes throughout the state, and free textbooks in high schools. Bumpers, however, in his two terms went beyond the traditional reform preoccupation with schools and roads to broaden services to the elderly and disabled, rehabilitate the state parks, establish regional health education branches, underwrite community college operations, strengthen consumer protection, and jumpstart prison construction.

Bumpers’s aspirations for the U.S. Senate outweighed his interest in a third gubernatorial term, and the governor’s polls showed that Senator J. William Fulbright was vulnerable despite his longevity in office. In 1974, the senator suffered defections across the ideological spectrum over his longstanding opposition to civil rights measures as well as his sharp criticism of the Vietnam War. Bumpers easily won the first of his four terms in Washington DC.

In that election year, Orval Faubus once again attempted to regain his old office but lost to a veteran antagonist of the “Old Guard,” David Pryor. In the early 1960s, Pryor was a young state representative from Camden (Ouachita County) pushing for reforms opposed by the Faubus administration. Nevertheless, his 1974 gubernatorial campaign benefited from the backing of venerable power brokers such as Witt Stephens. Following the Rockefeller model, Pryor appointed female and Black leaders to the Arkansas Supreme Court and influential commissions, consolidated six agencies into a new Department of Arkansas Natural and Cultural Heritage, and strengthened oversight of state fund distribution to local governments and service providers.

In the face of an economic downturn, Pryor proposed late in his first term to slash the income tax by twenty-five percent while leaving it to local governments to decide whether to raise new taxes to support programs the state government could no longer afford. Local officials had scant appetite for this revival of decentralized authority, dubbed the Arkansas Plan, and pushed legislators to bury the initiative. The postwar expansion of state programs and spending was entrenched in the political culture.

The setback did not derail Pryor’s career. His personal amiability counted for a lot in a state where voters still expected to be courted personally, and his attempt to cut government down to size allayed suspicions over his early liberal reputation. In 1978, Pryor won a hotly contested race for the U.S. Senate seat previously held by John McClellan, who had died the previous year.

Fulbright, McClellan, and Representative Wilbur Mills, who retired in 1977, had towered over the U. S. Congress for decades, and their successors were unable to match their influence over landmark legislation. On the other hand, this older legislative generation was part of a Southern bloc with a shared party identification. Bumpers and Pryor, as well as Bill Clinton, forged lengthy careers in an era of Republican triumph throughout the Old Confederacy. What became known as the “Big Three” promoted education and economic development programs that earned the support of both African Americans and rural whites, a voting bloc that kept Arkansas in the Democratic fold.

Work and Industry in a Rural State

The state after World War II raced to catch up with the national economy by welcoming industries on the wane elsewhere. The closing of large factories in the Midwest allowed Arkansas to boast that its manufacturing sector grew at six times the national average in the 1970s. Personal income figures climbed as farm labor disappeared. Yet continued dependence on food-processing and clothing plants, with only modest additions of better-paying industrial operations, took its toll on wage growth. Beginning in the 1980s, these low-wage industries migrated to lower-wage labor areas overseas.

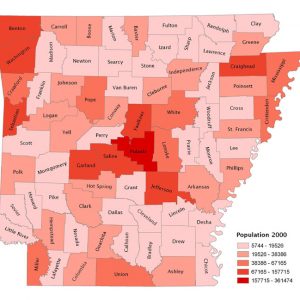

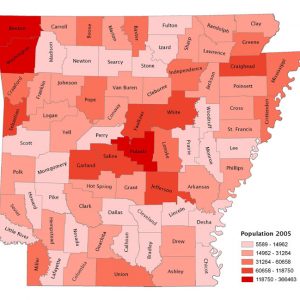

Manufacturing rebounded slightly in the 1990s before plummeting in the new century’s opening decades. Conversely, employment rose at the same time in the leisure and hospitality sector, but compensation levels were no higher—if not actually lower—than in the operations exiting the state. The state’s overall per capita income after World War II rose from half to about three-quarters the national level by the 1970s but languished at that stage into the twenty-first century. By 2020, regional differences in personal income had grown. Urbanized areas in Arkansas closed in on the rest of the United States, but rural centers lagged.

Manufacturing in Arkansas had fanned out throughout smaller towns, drawing on rural women to work on the processing lines and operate the sewing machines. As the apparel factories shuttered, female employees primarily worked the aisles of an expanding retail operation. One worker noted an advantage in the new setting: “Every day there was something different in Walmart. You didn’t do an assembly-line job at all.”

Although he started his own five-and-dime outlet in Bentonville (Benton County), Sam Walton saw little promise in these traditional anchors of downtown squares and opened his first Wal-Mart Discount City in Rogers (Benton County) in 1962. His company’s future remained uncertain until 1969, when he began in-house distribution of goods to his stores from a vast warehouse on the outskirts of Bentonville. By the 1990s, the company had pushed aside floundering giants such as Sears and Kmart to become the nation’s largest retailer. When the company offered groceries in the enlarged Supercenters, small-town shoppers happy to find better bargains also rued the pruning of food market rivals.

The chain’s lower prices consistently improved its bottom line when new customers came through the doors during economic downturns. Yet, what was known as the Great Recession of 2008 (subsequently overshadowed by the deeper collapse in 2020) revealed that the company was behind the curve in the online market, particularly compared to formidable Amazon.com. Just as Walmart strengthened its virtual presence, the COVID-19 pandemic confirmed the advantages of brick-and-mortar stores that could provide parking lot pick-ups. Although the company, in contrast to other businesses, racked up vibrant sales, its management was forced early in the outbreak to parry criticism from both workers and labor organizations that it had not adequately protected its employee associates from infection.

The pandemic inflicted a proportionately greater toll on the workforce of another global corporation that originated within and remained headquartered in Arkansas. Overseen by Don Tyson, Tyson Foods had introduced additional mechanization in its processing factories to fabricate a variety of value-added products from boneless chicken breasts to the menu items in fast-food franchise chains. Nevertheless, meat production remained more labor intensive than manufacturing operations in other industries, and the proximity of workers on the line fanned the virus that then flared from these plants. Companies’ revenue fizzled as managers struggled to keep processing lines moving and cope with supply chain disruptions. In April 2020, meatpacking operations (in Arkansas, mostly beef, pork, and poultry) were exempted from shutdown orders from local health authorities after President Donald Trump designated them essential industries. The firms’ profits rebounded by April 2021, despite soaring feed prices, as restaurants began welcoming back diners who ordered chicken breasts and other specialty cuts. By that point, Tyson Foods announced that the company had spent a half-billion dollars to bolster safety procedures and testing while also hiking wages to retain employees. Nevertheless, the Springdale (Washington and Benton counties) processor accounted for nearly a third of all COVID cases in the state between the spring of 2020 and spring 2021.

Volatile commodity price swings, however, were the historic norm in the industry. Beginning in the 1970s, Tyson Foods had exploited the churn to launch an acquisition campaign that shifted from buying up poultry firms to penetrating the beef and pork market. In 2001, John H. Tyson, who succeeded his father at the company’s helm, oversaw the frenzied battle that secured the giant Iowa Beef Producers. Tyson Foods had been largely successful in rebuffing union organizing efforts in its Arkansas processing operations, but the company’s entrance into labor strongholds outside the state spurred a new set of confrontations. Beyond the slaughterhouses, Midwestern swine and cattle producers were apprehensive that the contract growing system embedded in the poultry industry would be extended to their operations.

Even as the state consistently ranked near the top in broiler output, the number of contract poultry growers in Arkansas declined. The processing companies demanded growers construct larger, state-of-art chicken houses and meet rigorous production benchmarks. Tyson managers insisted they had a waiting list of rural residents angling for contracts and disparaged those growers who demanded federal oversight of contract provisions. Commercial growers tended to their flocks in about three-fourths of the counties in the state. Though not independent farmers, the place of these particular landowners in the global food chain contributed to the endurance of Arkansas’s rural character.

Life in the City, Life in the Country

By the twenty-first century, Little Rock (Pulaski County)—the state’s historic political, economic, and social hub—was outpaced in the rate of growth in population and per capita income by the chain of cities that made up metropolitan northwestern Arkansas. Led by Benton County, where vendors set up shop near the Walmart headquarters, that corner of the state grew primarily through the arrival of newcomers from elsewhere. Tyson Foods remained in Springdale even as it grew into an international behemoth, serving as a magnet for trucking firms that in turn made the region a transportation center. Long serving as the area’s market and financial center, Fayetteville (Washington County) gleaned advantages from the growth of the state’s major public university, the University of Arkansas. The college town atmosphere coupled with unabating prosperity attracted new residents as well as football fans. Rogers proved congenial to retirees due in part to its proximity to Beaver Lake, one of six reservoirs created in the White River Basin by dams built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

This federal project turned into a valuable subsidy when the communities formed a compact to secure additional grants and to rouse local support to build the infrastructure to transport water from the lake to the burgeoning housing developments. The separate locations of the largest employers in each of the major cities eased the formation and continuation of an effective regional planning and coordination council. Neighboring localities in other sections in the state rarely duplicated a similar pooling of resources and sense of common purpose. The same cooperative approach that had insured a reliable supply of drinking water bore fruit by 1998 when President Bill Clinton dedicated what is now the Northwest Arkansas National Airport.

The region’s maturation from the exclusive focus on the creation of wealth to channeling a portion into the founding of cultural institutions became spectacularly evident in the new century. Those capitalists who had founded and expanded modern Arkansas firms had become folksy celebrities within the state but had displayed limited philanthropic ambitions. In 2005, Alice Walton, the daughter of Helen and Sam Walton, announced that she was building in Bentonville a major museum dedicated to American art. Within a short time of the opening of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in 2011, its collection and design earned critical praise in national publications. Thousands of Arkansans who would have been otherwise unlikely to see significant works of art outside the pages of a book took advantage of the museum’s nearby location and free admission to the galleries.

The influx of outsiders into northwestern Arkansas was historically atypical in a state that, with the exception of a couple of decades, had recorded throughout the twentieth century more departures than arrivals. New residents with origins outside the United States were even rarer. Yet at one point in the 1990s, Arkansas led the country in the growth of its Latino population, many of whom had initially come to California and Texas from their homes in Mexico and Central America. First attracted to the poultry operations in the booming northwestern corner, Latinos soon established homes in Little Rock and southwestern Arkansas. In Sevier County, the Latino population grew from 632 residents in 1990 to 5,220 in 2010, making up thirty percent of the county’s total population. The majority of those living in De Queen, the county seat, were Latino.

While the new Arkansans continued to find work in chicken processing as well as construction, Latino entrepreneurs opened stores and businesses serving the growing immigrant communities and, in the process, enriched the cultural traditions within a state that had been staunchly biracial. Similarly, Latinos developed associations and guided media outlets that informed immigrants of useful resources to aid their adjustment and to cover issues not highlighted in the English language media. The Hispanic Women’s Organization of Arkansas formed in Washington County in 1999, El Centro Hispano began in 1997 as an outreach program of a Jonesboro (Craighead County) Catholic church, Arkansas United of Springdale was established in 2010 to advocate for immigrant rights, and El Latino brought out in 2001 its first edition in Little Rock. In 2020, community-based organizations met with and provided critical information to a team from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who came at the request of the beleaguered Arkansas Department of Health to examine the transmission of the coronavirus throughout Latino neighborhoods and Marshallese households in Benton and Washington counties.

The staggeringly disproportionate COVID-19 infection rates among these groups of Arkansans were linked at least partially to their disproportionate representation in the poultry processing facilities. The CDC researchers observed that the health department deployed “only one Spanish-speaking and 8 Marshallese-speaking case investigators” in the counties and that this shortcoming along with changing policies fed “the misinformation, myths and uncertainty” that hampered prevention and treatment.

New political debates had followed the path of the new residents. A 2002 poll revealed greater skepticism in northwestern Arkansas than in other regions as to whether the state benefited from the Hispanic migration. Calls for tougher action against illegal immigration came to the fore in the 2001 Republican primary for the northwestern district’s seat in the U.S. Congress. In the 2005 legislative session, the state senator from Springdale introduced a series of bills to cut benefits to undocumented residents. The proposals, denounced by the state’s Republican governor, were not enacted. Tom Cotton, elected to the U.S. Senate in 2014, emerged as one of the strongest proponents in the U.S. Congress for President Donald Trump’s proposals to limit immigration into the United States.

Latino families setting out for Little Rock generally found homes near African American working-class neighborhoods in the southwestern section of the city. Public officials and real estate developers over the decades had engineered the racial demarcation that channeled white families into the western and northern precincts. Whites had packed up and moved west before the full-scale integration in the 1970s of public schools. When the federal courts in the early 1970s struck down the devices Southern school districts had employed to evade integration, the enrollment of Little Rock private schools soared, as did white flight.

Early in the millennium, the charter school movement, reaping the bounty from the Walton Family Foundation, ignited debates over whether shrinking public control of education diminished equity and opportunity for children of color. The manipulation of school district boundaries in the central Arkansas metropolitan core had created a Black-majority school district in a city where whites outnumbered other ethnic groups. In 2007, sixty years after Governor Orval Faubus used the National Guard to prevent African American students from entering Central High School, a federal district judge released the Little Rock district from court oversight. In 2015, a new controversy flared when the state took over the Little Rock School District, setting aside the local board of directors when six schools in the district failed to meet education benchmarks.

The Latino population in Little Rock had grown nearly 170 percent between the 2000 census and the 2010 count, creating a majority-minority demographic in the capital, even with the white plurality. In 2018, Frank Scott became the first African American chosen in a popular election to serve as the Little Rock mayor.

African Americans by the second decade of the twenty-first century became a larger proportion of the overwhelmingly white suburbs and exurbs in central Arkansas, although their over-representation in low-paying service jobs in these areas contributed to the continued disparity between white and Black income, a gap that exceeded the national gulf. African Americans were more likely than white Arkansans to live in urban centers, which sustained the continued expansion of the Black professional class. A greater share of college graduates, along with the rising number of African-American women in managerial positions, boosted the numbers of Black households that earned incomes of $50,000 or higher. Nevertheless, a spectrum of economic and social measures confirmed the endurance of discrimination and exclusion. As was the case with Latinos, African Americans in the state were more likely than whites to suffer from the coronavirus, representing one instance in which Arkansas adhered to the national pattern.

African Americans streamed out of the Arkansas Delta in a wave that surged during World War II and flowed onward through the 1970s. Depopulation gained steam in the twenty-first century, though mainly whites were the ones who shook off Delta dirt. By this era, abandoned sharecropper cabins were no longer standing as mute evidence of an extinct plantation economy, but travelers in the region could not miss the winnowing of towns reflected in the shadows of empty stores and houses. The shift to large industrial farms relying upon mechanization and chemicals accelerated with the easing of federal rice allotments and then their abolition in the 1970s. The new crop surpassed in value soybeans, corn, and cotton as the state became the leading rice producer. In contrast to the other traditional Delta crops, every acre of rice was irrigated, and depletion of aquifers by the new century confronted farmers with water shortages commonly associated with more arid states.

The state continued to expand upon its 1950s economic development program that was intended to recruit companies through tax breaks, discounted loans, infrastructure, and direct subsidies. Governors of both parties touted this approach to boosting the state’s income and were particularly delighted with a 2007 program that permitted them at their discretion to distribute substantial cash grants to prospective employers. The state chamber of commerce and the Arkansas Economic Development Commission pointed to Jonesboro, which posted growth numbers rarely seen outside the northwestern or central sections, as well as specialized steel plants near Blytheville (Mississippi County), as evidence that public assistance in return for private investment paid off even in the battered Delta. Yet, unemployment stalked eastern Arkansas counties where the population was disproportionality elderly or younger than eighteen. Federal assistance to households anxious over food and healthcare was dwarfed by Department of Agriculture payments to Delta farm operations. Rural poverty not only took a toll on Arkansas citizens but remained a daunting obstacle to the state reaching national economic and social norms.

Cultural and Social Shifts

In the 1970s, state government incorporated tourism into its efforts to stimulate economic growth. While the campaigns to win over corporate investment emphasized low wages and friendly policies, the state marketed undeveloped scenic landscapes to rake in tourist dollars and attract retirees. In 1995, the General Assembly replaced “Land of Opportunity” with “The Natural State” as the state nickname. Voters in the following year gave officials the means to upgrade and expand the state park system by bumping up the state’s sales tax. The measure spread the revenue among several agencies that were charged with using the funds to conserve natural and historical assets. Among the beneficiaries were the historical museums overseen by the state, ranging from the Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover (Union County) dedicated to the oil industry; the Delta Cultural Center in Helena (Phillips County) exploring the labor, environment, and music of the region; and the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center examining through a variety of media the African American experience in the state.

By the 2000s, the permanent shutdown of manufacturing plants in rural sections was unmistakable, as was the drive by community boosters to promote outdoor activities and heritage sites to visitors and leisure-oriented businesses. Towns across the state had long staged summer festivals that celebrated local resources and historic milestones. More broadly, the extended movement to preserve Ozark folk culture, originating in the New Deal programs during the 1930s, had birthed musical festivals and supported craft production. In 1973, the state opened the Ozark Folk Center State Park in Mountain View (Stone County) to welcome visitors to observe artisans at work and to gather for performances echoing traditional music.

Undisguised economic development ambitions drove, in part, the local preservation campaigns that gathered momentum in the twenty-first century. Communities could tap state agencies and organizations for guidance. While not approaching the level available for factory recruitment, the cultural assistance programs were fruitful in supplying expertise and identifying grant sources. A portion of the 1996 tax increase was designated for the Department of Arkansas Heritage, which housed the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, which in turn was home to Main Street Arkansas. Revenue from an earlier tax on real estate transactions had put the preservation program on a stronger footing than its counterparts in other states. The impressive number of Arkansas towns boasting downtown commercial centers that had earned a place on the National Register for Historic Places revealed new perspectives in how communities regarded their history and their economic future.

The growing conviction among business and political interests that the fate of their localities required attention to quality of life issues, specifically in terms of offering the same amenities in dining and entertainment found in larger cities, provoked the uncorking of local conflicts that had seemed long settled. Arkansas, unlike almost any other state, was almost equally divided before 2000 between wet and dry counties, and the status quo held firm due to the stringent petition requirements for kicking off local option elections. Yet, in the first decade of the new century, proponents for alcohol sales in a number of persistently dry counties, including Clark, Columbia, and Sharp, overcame the opposition of influential evangelical ministers, as well as liquor store owners just across the county lines. In most of the local option contests, campaign contributions flowing from Walmart were decisive in swinging the outcome in favor of legalizing liquor. A successful wet vote permitted the mega-retailer’s local Supercenter to add beer and wine to the grocery aisles.

Similar turnarounds by Arkansas voters on other traditionally charged issues reset which policies still aligned wiht the state’s enduring social conservatism. In 2016, Arkansans approved an amendment to the constitution allowing doctors to prescribe medical marijuana to patients, placing the state alongside Florida as the first in the South to authorize the use of the drug. By the twenty-first century, Arkansas still trailed surrounding states that had legalized gambling to stoke state coffers. Proponents had been consistently frustrated in their attempts to overturn at the ballot box the anti-gambling provisions in the state constitution. In 2008, however, voters approved a state-run lottery by a wide margin, reserving a portion of the proceeds for higher education scholarships. While the General Assembly in 2005 had opened the door to Oaklawn and Southland race track venues to install electronic gaming devices, voters in 2018 ratified Amendment 100, which restored casinos to Hot Springs by authorizing their operations at Oaklawn and Southland in West Memphis (Crittenden County), as well as in Jefferson and Pope counties.

But the social conservatism was in full evidence in the state as the antiabortion movement gained sway in conservative states in the decades following the 1972 Roe v. Wade decision. In 1988, voters adopted an amendment to the constitution that required state government to “protect the life of every unborn child from conception to birth” to the degree allowed under U.S. Constitution. Throughout the remainder of the twentieth century and into the next, the General Assembly approved a series of restrictions that sharply reduced the number of clinics providing abortions while also passing more sweeping measures that were set aside in federal courts. In June 2022, those judicial precedents were set aside by the U.S. Supreme Court, “triggering” or implementing in Arkansas a 2019 law that outlawed abortions except when necessary in a medical emergency to save the life of pregnant women.

In profoundly conservative Arkansas, advocates for LGBTQ+ protections and equality followed the African American civil rights model to instigate and seize upon the opportunities of landmark court decisions. The struggle, however, spanned decades. In 1977, the General Assembly confirmed early measures criminalizing homosexuality and rebuffed repeal proposals in subsequent sessions. The Arkansas Supreme Court in Jegley v. Picado (2002) struck down the law based on provisions in the state constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court cited the Jegley ruling in its Lawrence v. Texas decision (2003) that overturned state laws outlawing same-sex relations. In 2011, the state Supreme Court set aside the law that prohibited gay and lesbian couples from fostering children, and subsequent attempts to revive the ban did not survive court scrutiny.

In 2004, the voters overwhelmingly amended the Arkansas Constitution to define marriage as “the union of one man and one woman.” Ten years later, a Pulaski County circuit judge revoked the provision and did not grant the state’s request for a stay. The following day in Eureka Springs (Carroll County), Kristin Seaton and Jennifer Rambo became the first same-sex couple in Arkansas to marry. The state Supreme Court soon halted the issuance of marriage licenses to same-sex applicants but did not issue a final decision before the U.S. Supreme Court in 2015 upheld marriage equality. In 2017, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that the state’s civil rights statute did not include gay and lesbian citizens and overturned a Fayetteville ordinance that protected them from employment and housing discrimination. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the 1964 U.S. Civil Rights Act prohibited discrimination of LGBTQ+ citizens in employment.

E. Lynn Harris, who grew up in Little Rock and attended the University of Arkansas, wrote widely read novels in which the experiences of gay African American protagonists reflected the author’s own struggles to acknowledge his sexuality. Other Arkansas writers earned critical recognition for distinctive works that cut against the grain of contemporary literature through depictions of characters who veered back and forth along the edges of society. The figures in Charles Portis’s novels could not stay put, while Donald Harington returned often in his many books to the otherworldly Stay More that reflected the earthy Ozark culture. True Grit provided Portis the wherewithal to keep writing comic masterpieces that did not crack the bestseller lists but roped in devoted readers wide and far. Harington reshaped upland traditions and experience through wildly inventive narratives that subverted the romantic images of quaint and rooted communities.

The plain style of the poetry of Miller Williams heightened its emotional complexity, speaking directly and below the surface to readers from the many walks of life that Williams knew intimately. Like these writers, architect E. Fay Jones remained tethered to Arkansas. The state’s landscape influenced his architectural designs that, in turn, re-framed the natural world for observers within the structures. Art more authentically represented the state than tourism brochures.

Continuity and Change in Politics

By the 1980s, no single person could wield the degree of influence over the state legislature once exercised by Hamilton Moses of Arkansas Power and Light or Witt Stephens, the financial and natural gas magnate. Corporate officers and lobbyists for the poultry and trucking companies, utilities, insurance firms, and agricultural and timber interests vied for the attention of legislators, who also were compelled to listen to representatives from labor, education, social welfare agencies, and local governments. Competing interest groups also angled to gain advantage from expanding state bureaucracies. These agencies enjoyed greater sway over policy in the wake of a constitutional amendment that limited the time in office of elected officials.

The 1992 term limits amendment, more stringent than ones in other states, dislodged long-serving legislators but was not an avenue for Republicans to claim a large share of seats long monopolized by Democrats. Arkansas trailed the rest of the South in shrugging off its old allegiance. Neither did term limits ensure a more diverse membership in the General Assembly. Throughout the 1990s, the proportion of women in the House was not far from the national average, but in 1999 the Arkansas Senate was the only lawmaking body in the nation that was all-male. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, the female delegation in both chambers trailed national but not regional averages.

In 1999, Blanche Lincoln became the first woman since Hattie Caraway to represent Arkansas in the U.S. Senate. In 2014, the voters elected a woman for the first time to the attorney general’s post, and balloting resulted in women holding the majority of seats on the Arkansas Supreme Court by 2015. Women remained more likely to gain offices at the local level, but the low percentage of registered female voters in the state was a troubling survival of the barriers that impaired democracy.

By the 1970s, African Americans in Arkansas were more likely to have registered to vote than Black residents in other Southern states. Yet, African Americans did not scale the structural exclusions to gain footholds in the General Assembly until filing federal lawsuits that forced the state to redraw legislative districts. Black representation in the legislature during the early twenty-first century tracked national averages although lagging behind most Southern states.

In 2012, the House, still under control of Democrats, selected Rep. Darrin Williams as speaker for the next regular session. He would have been the first African American to preside over the chamber, but a white Republican ended up wielding the gavel when the Democrats lost their majority in elections that fall. The proportion of African American legislators seemed little affected by the Republican takeover of the General Assembly: in 2009, ten Black representatives held seats in the House and four in the Senate; in 2019, thirteen African American representatives served alongside three Black state senators.

As was the case with women, local offices offered greater chances for Black candidates. In addition to Mayor Scott in Little Rock, African Americans were elected mayors in 2018 for the first time in Camden (Ouachita County), El Dorado (Union County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and West Memphis. Two years earlier, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) had chosen the city’s first African American woman mayor. Following the 2020 elections, Arkansas remained the only former Confederate state that had not elected an African American to the U.S. Congress or to statewide office.

Ten years after Winthrop Rockefeller lost his reelection bid in 1970, Democratic leaders were confident that the tenure of three popular governors, two of whom had been elected to the U.S. Senate, and dominion over the General Assembly verified their party’s invulnerability. The 1980 election, however, appeared to lend credence to the popular folk wisdom of pundits that Arkansas voters were singularly independent. Arkansans reversed their earlier support for Jimmy Carter, the incumbent Democratic president, in favor of conservative Ronald Reagan, while also turning out after one term Governor Bill Clinton in favor of his Republican opponent, Frank White. As a free-market businessman and Protestant evangelical, White was closer to the ascendant conservative wing of the Republican Party than to the moderate reformism of Winthrop Rockefeller.

White’s program emphasized budget cuts, and its modesty led to a minimum of friction with the Democratic legislature. Rather than boost state taxes, White signed a measure that gave cities and counties the green light to impose sales taxes. Localities speedily and frequently asked residents to approve the levies, and by the early twenty-first century total sales taxes throughout the state ranked among the highest in the nation.

In 1981, the White administration attracted national attention with its vigorous defense of Act 590, a law requiring the teaching of “creation science” alongside evolution in public school classrooms. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) argued in its federal lawsuit that the new act employed state funds to advance a religious doctrine. The state did not appeal Judge William Overton’s decision striking down the law on constitutional grounds.

Clinton made his first comeback in 1982 by winning the rematch with White. Believing that an activist reform agenda in his first term had angered voters, a chastened Clinton asked little of the legislature until the Arkansas Supreme Court held that the method of funding public schools violated the state constitutional requirement for equitable distribution of resources. A 1983 special session of the General Assembly approved the governor’s wide-ranging proposals, which grew from the recommendations drafted by a study commission headed by Hillary Rodham Clinton. The Arkansas Education Association fought a proposal requiring current teachers to pass a test to achieve recertification and remained embittered toward the governor when the legislature adopted the provision.

Persistent economic woes in the state and the nation during the 1980s checked Clinton’s attempts to expand his educational program and secure additional tax increases. In 1990, Clinton’s tepid launch of the campaign for reelection to a fifth term suggested that he was both spent from a decade of political wars and was already pointing toward a presidential run. Unexpectedly, the 1991 legislative session proved among the most constructive in the modern era. Court-ordered redistricting unseated several eastern Arkansas stalwarts who had blocked earlier initiatives.

This time, Clinton won from legislators tax increases for schools and expansion of the community college system as well as a statewide highway maintenance and construction program. This session solidified Clinton’s record as a Southern moderate who believed that both his state’s well-being and individual opportunity were advanced by a program of better schools, racial inclusion, professionalism in government, favorable business policies, and upgraded infrastructure. This reform agenda, originally launched by Governor Rockefeller, later became the non-ideological, “third way” policy strategy of the Clinton presidential administration.

Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign victory raised the profile of an often-overlooked state while also provoking opponents to revive old stereotypes. Charges that the state’s political system remained mired in corruption and cronyism deepened with the investigation into loans the Clintons secured in the late 1970s to develop an Ozark resort. The Whitewater venture fell apart when the real estate market collapsed. Judge Kenneth Starr, appointed as special prosecutor in 1994, took no action against the couple on their Whitewater investment but reported to Congress that Bill Clinton’s testimony in a sexual harassment case offered possible grounds for impeachment. The exhaustive sweep by Starr’s office of the state did not lead to indictments of officials on public corruption but did ensnare the sitting governor, Jim Guy Tucker, who stood trial on charges related to private business investments prior to taking office. The outcome altered the course of the state’s politics.

In late 1992, Tucker, the state’s lieutenant governor, became the chief executive when Clinton resigned before his presidential inauguration. Although viewed as liberal with solid ties to the labor movement when he served in Congress, Tucker backed a stringent criminal justice measure and took a fiscally conservative approach to budgeting. In 1994, he won a full term decidedly, but the voters rebuffed his subsequent proposals to convene a constitutional convention and to issue bonds for a massive highway overhaul.

In May 1998, a federal jury convicted Tucker on one count of mail fraud and one count of conspiracy arising from a Small Business Administration loan application. Tucker announced that he would step down in July in accordance with the constitutional ban on those convicted of felonies from holding office. On the day set for the transfer of power, Tucker backtracked, claiming that jury bias provided a basis for overturning his conviction. For several hours, both Tucker and Lieutenant Governor Mike Huckabee claimed to be the governor of Arkansas; the potential constitutional crisis passed when Tucker relented by the end of the day.

The new governor, Huckabee, was the third Republican to hold the office in the twentieth century and arrived at a time when the Rockefeller vision of a competitive two-party system seemed close to realization. The Republican Party’s dominance of northwestern Arkansas ensured that any Third District congressperson would sit on the Republican side of the chamber for the foreseeable future. Beginning in 1993, a Republican, Jay Dickey, represented the largely rural Fourth District. The 1996 election produced the state’s first Republican U.S. senator since Reconstruction, Tim Hutchinson, and installed Winthrop Paul Rockefeller, Governor Winthrop Rockefeller’s son, as lieutenant governor. The Republican cause was also advanced in 1991 by the acquisition of the liberal Arkansas Gazette, the influential statewide newspaper, by Walter Hussman, the publisher of the rival Arkansas Democrat. The editorial pages of the newly christened Arkansas Democrat-Gazette chastised Democrats and advocated conservative principles.

Huckabee’s policies also demonstrated a cross-current of Rockefeller activism and movement conservatism. A Southern Baptist minister, Huckabee often touted moral examples as the better corrective to social problems than government initiatives, and he enthusiastically cut taxes during the flush 1990s. Nevertheless, he worked with social welfare advocates to develop the ARKids First program to extend healthcare to the children of the working poor, andin 1999, he won public support for the largest highway bond issue in the state’s history. After 2001, nearly every state faced a fiscal crisis; yet Huckabee, in contrast to other Southern Republican governors, supported tax increases as well as budget cuts to address revenue shortfalls. Democrats applauded and Republicans frowned on his opposition to anti-immigrant bills in the 2005 session. Huckabee also backed a measure that same year to make undocumented residents eligible for in-state college tuition rates and state-funded scholarships. The bill fell short in the state Senate after Attorney General Mike Beebe, a Democrat, issued an opinion that such a measure ran afoul of federal law, a position Beebe reconfirmed four years later when he was serving as governor.

In 2002, when the Arkansas Supreme Court agreed with the plaintiffs in the Lake View School District that the state had once again permitted the public school system to fail the constitutional test of equitability, Huckabee not only conceded the need for new revenue but also centered his education plan on the politically risky demand for massive school consolidation. The Democratic majority in the General Assembly angered the governor when it shuttered far fewer rural school districts while boosting the sales tax to funnel new monies to the ones with a shaky financial base.

In 2006, the legislature once more grappled with essential funding for the education of all students when the court found that the state had failed to live up to its earlier agreements. The legislature not only raised funding that year but affirmed that the funding of K–12 education would be the priority in the state’s budget even if other state services suffered severe cuts. In 2007, the Arkansas Supreme Court declared the school system constitutional and ended the Lake View case.

In that same year, Huckabee left office after staying as long as possible under term limits and soon launched his first campaign for president. While the former governor remained a popular figure in the state, the Republican Party absorbed notable setbacks in its bid to reach equal footing with its rival. In 2000, the Fourth District congressional seat flipped back to the Democrats with the election of Mike Ross, and two years later Mark Pryor, son of the still well-liked former senator, denied Senator Tim Hutchinson a second term. In 2006, Hutchinson’s brother, Asa, failed to give the state its first consecutive Republican administrations when he was swamped by Mike Beebe.

Just as Huckabee’s favorable ratings did not jumpstart his party’s fortunes, voter esteem for Beebe would not stave off the collapse of Democratic political control. The new governor, over the course of twenty years in the state Senate, had dislodged the entrenched kingpins to become a less heavy-handed but effective leader of the chamber. In his first gubernatorial term, Beebe put in motion the reduction of the state sales tax on groceries as a relief for lower-income residents while also guiding the state through the 2008 recession without draconian budget cuts or a general tax increase. Republican efforts to hitch Beebe to national liberal Democratic figures worked no better than when deployed against his predecessors. In the 2010 general election, he amassed a victory margin larger than what he achieved four years earlier.

Yet, the Democratic candidates for the other constitutional offices and the two congressional seats, along with Senator Lincoln, succumbed to an unforeseen wave of Republican triumphs. The antipathy of white voters in Arkansas toward President Barack Obama, whose policies to mitigate the housing crisis in 2009 had ignited the nationwide conservative Tea Party movement, contributed to the tectonic shift at the polls. After the next legislative election cycle, Beebe became the first Democratic governor in the history of the state to confront a General Assembly session controlled by the opposition party. The scope and abrupt swing of Arkansas from a one-party Democratic state to a one-party Republican state defied plausible analysis but in the aftermath, confounded Winthrop Rockefeller’s conviction that a strengthened GOP would stoke a competitive party system.

The Democratic governor’s relations with the Republican legislature were less brittle and wary than what had been common during the Huckabee era of split government. Beebe’s pragmatic reputation was burnished when administration officials collaborated with legislative leaders to extend Medicaid benefits to a greater share of low-income Arkansans by reconfiguring a section of the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA). Although many Republican members had strenuously campaigned against the ACA (or “Obamacare”), the Medicaid proposal narrowly gained the required super majorities in the General Assembly. The bipartisan measure within three years cut in half the number of uninsured in the state and, in combination with the earlier bipartisan ARKids program, covered an even greater share of children.

The role of bipartisanship in Arkansas government appeared to become less relevant after 2014, when Asa Hutchinson won the governor’s seat vacated by the term-limited Beebe. The Republican majority in the General Assembly had grown to the point that the surviving Democratic members were too few to block appropriation measures that required three-fourths aye votes. Still, Hutchinson would come to need those Democrats to offset Republicans who believed that the Medicaid expansion ran afoul of conservative principles.

Hutchinson had taken positions in the George W. Bush administration following two terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He had been one of the House managers arguing the case against Bill Clinton during the impeachment proceedings. The extended Hutchinson family were movers and shakers among northwestern Arkansas Republicans, the wing more closely associated with social conservatism than were the business-oriented members in the central metro region.

Asa Hutchinson, however, centered his program from the beginning of his administration on boosting employment through financial and regulatory relief for business. The governor was wary of explosive social issues. Facing possible corporate and tourism boycotts, he thwarted in 2015 a broadly drawn measure that gave license to discriminate against LGBTQ+ individuals on religious grounds. In 2021, however, his veto of a bill that would outlaw gender-affirming medical treatment for minors, the first of its kind in the nation, did not stop the state legislature from meeting soon thereafter to override his veto, and the bill entered law as Act 626.

Early in Hutchinson’s tenure, legislators readily accommodated the governor’s phased, across-the-board income tax reductions, but the Republican majority’s commitment to quash Medicaid expansion threatened the viability of those revenue cuts. The funding for the program from the federal government provided critical ballast for the state’s budget. After narrowly winning renewal of Medicaid expansion in his first legislative session, the governor obtained more comfortable margins in subsequent sessions for a program that continued to provide benefits to a large sector of the population. Hutchinson, confident in Democratic support, maneuvered to win Republican votes by slightly altering the system and insisting that he had unshackled it from the original Obamacare model. In 2017, the legislature endorsed the administration’s “Arkansas Works” version; after a federal court decision voided the work requirement for recipients, the governor in 2021 gained approval for channeling the unemployed into a less comprehensive healthcare plan that he dubbed “ARHome.”

Following his easy reelection, Hutchinson had little trouble piloting his merger of forty-two agencies into fifteen through the 2019 legislature. Governors since the Faubus era had promoted government reorganization as a relatively cost-free strategy to demonstrate efficient stewardship of tax funds. Governors also historically confronted a less accommodating General Assembly late in their terms. Though Hutchinson promoted conservative initiatives that distinguished him from his predecessors in the political reform era that began with Rockefeller, he fell out of step with the steady rightward bent of the legislature.

Following the 2020 election, Republicans claimed a greater number of seats in the legislature, although fewer were held by women. Arkansas was among the six states that widened their previous margin for Donald Trump while also tallying fewer ballots. Only Oklahoma notched a smaller voter turnout. The low participation levels that had been the hallmark of Democratic one-party government continued under Republican one-party government.

The 2021 legislative session earned recriminations nationally and sparked unease in the state’s corporate offices by enacting with large majorities a series of restrictions on transgender citizens. Denouncements of the laws in national editorial columns echoed the disapproval by major health and education organizations. The governor later revealed that the passage of similar laws in other Southern states eased his concerns about potential reprisals against the state’s tourism industry and business recruitment campaigns. Arkansas also closed ranks with its neighbors when the General Assembly enacted new obstacles to absentee balloting and expanded the right of the state election commission and the legislature to review alleged voting irregularities by local officials.

No governor in the modern era, of course, had confronted the threats to life posed by the coronavirus pandemic and to livelihoods from the accompanying recession. Hutchinson took steps with public health emergency orders that were designed to check the spread of the virus without slowing the resuscitation of the economy. Along with a handful of Republican governors, he did not issue a shelter-in-place order and permitted a greater range of businesses to operate than was the case in most states. In the early summer of 2020, he began easing those restrictions even as the state’s cases and deaths rose. The CDC had earlier issued federal guidelines recommending that a phased reopening of a state’s economy should follow a “downward trajectory” of confirmed cases. Legislators seethed when the governor in July 2020 issued a mask mandate that also stirred resistance from local sheriffs and police. Though rarely enforced by authorities, the mandate gave leeway for local governments and private businesses to require masks to be worn by employees and customers.

Hutchinson did not reimpose restrictions in the winter of 2020–21 as the numbers of people in Arkansas contracting and dying from COVID-19 rose proportionately to among the highest in the nation. The gradual availability of vaccines for the disease dampened its spread, and the governor withdrew by April the emergency directives. Initially, state health officials struggled to allot the insufficient supplies of vaccines to those wanting the shots, but the numbers of residents spurning the protection pushed Arkansas by the summer to near the top of states with the largest unvaccinated population.

In August 2021, the more contagious and possibly deadlier Delta variant of the original coronavirus spiked a new surge of infections. The governor emphasized the need for personal responsibility rather than public health regulations, a stance reflecting not only his conservatism but newly imposed legal limits on this powers. Act 1002 of 2021 prohibited state and local governments as well as agencies, including schools, from requiring face coverings unless authorized through legislation. Hutchinson summoned the General Assembly into special session before the start of the 2021–22 school year to revise the law so that local school districts could require masks to protect students under twelve years old, a group then ineligible for a vaccine. The legislature rebuffed this nominal public health safeguard. Many districts, nevertheless, did adopt mask policies after a state district judge in August 2021 blocked the law.

Major federal stimulus spending programs authorized by Congress in 2020 and 2021 shored up both personal incomes and state’s public coffers. Hutchinson welcomed the dollars that, among other benefits, made feasible his aim to extend internet broadband capabilities throughout rural sections as well as to justify another round of income tax cuts. Arkansas’s persistent reliance on federal funding remained a basic feature of the state’s modern economy. On the other hand, state lawmakers in Washington had once unfailingly spared no effort to wrangle funds for constituents, but the latter-day congressional delegation broke the mold, uniformly opposing recovery measures introduced by the Joe Biden presidential administration.

Into an Uncertain Era

By the 1990s, the eclipse of the old society and economy through the integration of Arkansas into the national mainstream had made it possible for an Arkansas political leader to become an American president. Three decades later, the sweep of the coronavirus strained the government services that had markedly improved since the 1960s. The hardships for citizens long burdened by poverty and inequities were sharpened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic also exposed growing disfavor toward the aims and approaches of the waning reform era that had stretched from the 1960s into the new century. Hutchinson represented a wing within the Republican Party that was confident that business and non-public organizations could effectively promote general well-being. Government, in this view, was largely on the sidelines, complying with requests for favorable regulations and targeted subsidies of private operations. Throughout the COVID crisis, the governor insisted that Arkansans would defy robust public health initiatives. He preferred to encourage voluntary compliance with health guidelines while tolerating limited mandates at the local level. The Republican-controlled legislature adopted measures to stem local health regulations as well as undermine local governance of elections. In August 2021, Tyson Foods, ahead of nearly all major American corporations, required all of its employees to become vaccinated against the virus. Two months later, state legislators approved a way for resisters to gain exemptions to private employer vaccine mandates. Majorities in the General Assembly, in contrast to their predecessors, did not defer to major employers.

Lawmakers also tapped into segregation-era assertions of state supremacy through the passage of the Arkansas Sovereignty Act of 2021 that overrode new federal regulations infringing on personal gun rights. This expansion of state authority was accompanied by proposals from emerging Republican candidates to go beyond the Hutchinson tax cuts to eliminate the income tax.

The pre-Rockefeller governing model was characterized by pervasive corruption, elevation of private over public interest, ineffectual agencies, and the unequal treatment of minority groups. The succeeding era, marked by pragmatism and expanded public services, had extended into early twenty-first century but waned with the solidification of the new political order during the time of plague. Prosperity in Arkansas had risen in tandem with the evolution of government toward greater effectiveness, representation, and equality. Contemporary observers were left to speculate as to whether the landmarks of the reform years would endure or erode through the reemergence of practices and policies from the older, traditional regime.

For additional information:

Aviv, Rachel. “Punishment by Pandemic.” New Yorker, June 22, 2020, pp. 56–65.

Barth, Jay, and Janine Parry. “Arkansas: Trump Is a Natural for the Natural State.” In The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be: The 2016 Presidential Election in the South, edited by Scott E. Buchanan and Branwell DuBose Kapeluck. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018: 127–146.

Blair Diane D., and Jay Barth, Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2nd ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Blair, Diane. “The Arkansas Plan: Coon Dogs or Community Service.” In Arkansas Politics: A Reader, edited by Richard P. Wang and Michael Dougan. Fayetteville: M & M Press, 1997.

———. “The Big Three of Late Twentieth Century Politics: Dale Bumpers, Bill Clinton, and David Pryor.” In Arkansas Politics: A Reader, edited by Richard P. Wang and Michael Dougan. Fayetteville: M & M Press, 1997.

Bernstein Carl. A Woman in Charge: The Life of Hillary Rodham Clinton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Blevins, Brooks. Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, and Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Brummett, John. Highwire: From the Backwoods to the Beltway—The Education of Bill Clinton. New York: Hyperion, 1994.

Bumpers, Dale. The Best Lawyer in a One-Lawyer Town: A Memoir. New York: Random House, 2003.

Carter, Daryl. Brother Bill: President Clinton and the Politics of Race and Class. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

CDC AR-3 Field Team. “Summary Report: COVID-19 among Hispanic and Marshallese communities in Benton and Washington Counties, Arkansas.” Washington DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020.

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Davis, John C. From Blue to Red: The Rise of the GOP in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2024.

Dumas, Ernest. The Education of Ernie Dumas: Chronicles of the Arkansas Political Mind. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2019.

Hinshaw, Jerry. Call the Roll: The First One Hundred Fifty Years of the Arkansas Legislature. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1986.

Holley, Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Black Migration, and How They Shaped the Modern South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Goss, Kay C. Mr. Chairman: The Life and Legacy of Wilbur D. Mills. Little Rock: Parkhurst Brothers Publishers, 2012.

Gray, Laguana. We Just Keep Running the Line: Black Southern Women and the Poultry Processing Industry. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

Jones-Branch, Cherisse, and Gary T. Edwards, eds. Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Kilpatrick, Judith. There When We Needed Him: Wiley Austin Branton, Civil Rights Warrior. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

———. “A Southern Road Less Traveled: The 1966 Arkansas Gubernatorial Election and (Winthrop) Rockefeller Republicanism in Dixie.” In Painting Dixie Red: When, Where, Why, and How the South Became Republican, edited by Glenn Feldman. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

Laymon, Sherry. Fearless: John L. McClellan, United States Senator. Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing, 2011.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. The Retail Revolution: How Wal-Mart Created a Brave New World of Business. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009.

Maraniss, David. First in His Class: A Biography of Bill Clinton. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Moreton, Bethany. To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Parry, Janine A. “‘What Women Wanted’: Arkansas Women’s Commissions and the ERA.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 265–298.

Pierce, Michael. “John McClellan, the Teamsters, and Biracial Labor Politics in Arkansas, 1947–1959.” In Life and Labor in the New South, edited by Robert H. Zeiger. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012.

Pryor, David, with Don Harrell, A Pryor Commitment: The Autobiography of David Pryor. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2008.

Riffel, Brent E. “The Feathered Kingdom: Tyson Foods and the Transformation of American Land, Labor, and Law, 1930-2005.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2001.

Schwartz, Marvin. Tyson: From Farm to Market. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Smith, C. Calvin, ed. Educating the Masses: The Unfolding History of Black School Administrators in Arkansas, 1900–2000. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Strausberg, Stephen. From Hills and Hollers: Rise of the Poultry Industry in Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, 1995.

Stephens, Donna Lampkin. If It Ain’t Broke, Break It: How Corporate Journalism Killed the Arkansas Gazette. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Thompson Brock. The Un-Natural State: Arkansas and the Queer South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Urwin, Cathy Kunzinger. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–71. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Ward, John. The Arkansas Rockefeller. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

Whayne, Jeannie. Delta Empire: Lee Wilson and The Transformation of Agriculture in the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State Press, 2011.

Zajicek, Anna M., Allyn Lord, and Lori Holyfield. “The Emergence and First Years of a Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970–1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Summer 2003): 153–181.

Zelizer, Julian E. Taxing America: Wilbur D. Mills, Congress, and the State, 1945–1975. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Ben Johnson

Southern Arkansas University

This was a great review of a time and place I participated in. I was an attorney in El Dorado, a state representative from Union County, and captain in the U.S. Navy Reserve, plus an Eagle Scout at First Methodist Church in El Dorado. David Pryor and I are the same age and traveled the “Road” together to the University of Arkansas and the Arkansas Legislature. The air gets thin above ninety.