calsfoundation@cals.org

Winthrop Rockefeller (1912–1973)

Thirty-seventh Governor (1967–1971)

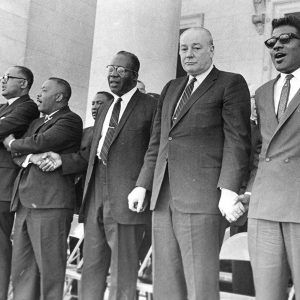

As governor, Winthrop Rockefeller brought economic, cultural, and political change to Arkansas. “W. R.” or “Win,” as he was known, brought an end to the political organization of former Governor Orval E. Faubus and created a political environment that produced moderate leaders like Dale Bumpers, David Pryor, and Bill Clinton. Rockefeller’s personal belief in racial equality became well known, and he ushered in an era that saw large numbers of African Americans elevated to high positions in state government. Rockefeller was a “transitional leader” in the sense that he helped discredit the “Old Guard” domination of the Faubus years and, in so doing, made Arkansans more receptive to political and social change.

Winthrop Rockefeller was born on May 1, 1912, in New York City to John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. The fifth of six children, Winthrop was not given a middle name. Winthrop’s grandfather, John D. Rockefeller, was the founder of Standard Oil Company—and a very rich man by the time his grandson was born.

Winthrop grew up a privileged child, with private tutors and attendance at Lincoln School at Columbia University Teachers College. He also attended Loomis School, another private preparatory school in Windsor, Connecticut. Rockefeller’s ease with the French language, which came in handy from time to time during his administration, betrayed his prep school education. Although popular with his classmates, Rockefeller withdrew from Yale University (where he had studied from 1931 to 1934) during his third year without taking a degree.

Rockefeller was unwilling to take a position at the top of the family oil empire immediately, so he took a job as an apprentice roughneck in the oil fields. Rockefeller later considered this to be the happiest years of his life. In 1937, he abandoned his independence and took a position with Socony-Vacuum, an oil company that grew out of the family’s Standard Oil of New York.

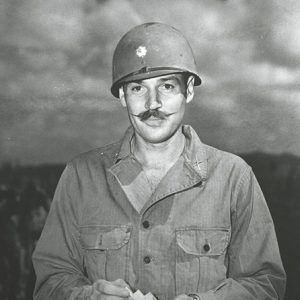

Rockefeller’s insistence on leading a lifestyle different from the family model continued during the World War II years, when he enlisted as a private in the U.S. Army on January 22, 1941, nearly a year before hostilities began. After completing Officer Candidate School, Rockefeller was given the rank of second lieutenant and became a machinegun instructor at Fort Benning, Georgia. In August 1942, Rockefeller was named commander of H Company, 305th Infantry Regiment, Seventy-seventh Division, Fort Jackson, South Carolina. He was promoted to captain in December 1942 and to major in November 1943.

A swashbuckling commander with a handlebar mustache, Rockefeller loved his World War II career. He saw considerable action in the south Pacific, including participating in the Battle of Guam and the invasion of Okinawa, where he suffered burns when his transport was hit by a kamikaze. He left the army with the rank of lieutenant colonel, having received the Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Cluster and the Purple Heart.

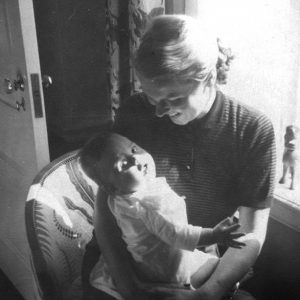

Rockefeller’s years after World War II were not happy ones. Still working at Socony-Vacuum, he chaffed at the restrictive lifestyle expected of him and his siblings. A heavy drinker known for his playboy lifestyle, Rockefeller often frequented chic cafes late at night with a movie star on his arm. He abruptly married an attractive blonde divorcee named Barbara “Bobo” Sears on Valentine’s Day in 1948. Soon they were the parents of a son, Winthrop Paul Rockefeller, but the marriage dissolved within a year.

Rockefeller fled to the very antithesis of New York chic society in early 1953, visiting an old army friend from Little Rock (Pulaski County), businessman Frank Newell. In less than a year, Rockefeller bought a large amount of land atop Petit Jean Mountain near Morrilton (Conway County), which he named Winrock Farms and developed into a showplace home.

Arkansans welcomed Rockefeller, and he quickly developed deep roots. He and his second wife, Jeannette Edris Rockefeller, were especially supportive of the Arkansas Arts Center (now the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts). The Rockwin Fund provided support for worthy causes across the state.

It did not take long for Rockefeller to attract the attention of Governor Orval Faubus. Desperate to build Arkansas’s stagnant economy, Faubus named Rockefeller to the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission (now the Arkansas Economic Development Commission) in 1955. Rockefeller took this work seriously, and by the time he left the commission after nine years, Arkansas had undergone a remarkable economic transformation. He claimed credit for bringing more than 600 new industrial plants to Arkansas, providing 90,000 new jobs. Industrial employment grew by 47.5 percent, and manufacturing wages grew by eighty-eight percent, compared to a national rise of thirty-six percent.

Rockefeller’s success with economic development, not to mention his famous name and vast fortune, brought him into politics. A Republican by family tradition, Rockefeller was appalled at the political climate in Arkansas. State government was controlled by the Democratic Party, but most of the real power rested in the hands of Governor Faubus. Having been in office for a decade by 1964, Faubus had used his appointive and patronage powers to build a seemingly invincible political empire.

Rockefeller mounted a strong campaign against Faubus in 1964, but Arkansas stayed with the Democratic Party that year by a vote of fifty-six percent for Faubus. Rockefeller quickly announced that he would be a candidate again in 1966.

The election of 1966 was a watershed in Arkansas political history, for it not only saw the election of the state’s first Republican governor since 1872, as well as a Republican U.S. congressman in northwestern Arkansas (John Paul Hammerschmidt), but it was an election in which black voters cast the deciding vote. The segregationist wing of the state Democratic Party mustered a final victory by nominating former state Supreme Court justice James D. (Jim) Johnson, a protégé of segregationist presidential candidate and Alabama governor, George C. Wallace. While Rockefeller welcomed black votes, Johnson refused to shake hands with black citizens. In the end, Rockefeller won with fifty-four percent of the vote.

Promising an “Era of Excellence,” Rockefeller submitted considerable reform legislation, but the results were mixed. Rockefeller’s major achievements as governor include several laws enacted during the 1967 legislature: adopting the state’s first minimum wage, tightening lax insurance regulation, and adopting a law to guarantee freedom of information. He ordered the Arkansas State Police to close illegal gambling operations in Hot Springs (Garland County). Black Arkansans found state government more accepting under Rockefeller, with the integration of the State Police being a signal accomplishment.

One of the legacies inherited from the Faubus administration was the unbelievably cruel Arkansas penitentiary system. Rockefeller hired a professional criminologist, Thomas Murton, to bring reform to the dismal scene. Murton turned out to be an impatient administrator, and he eventually exhumed graves that he claimed contained the remains of murdered convicts. When Murton refused to back down, Rockefeller fired him, which resulted in Murton charging that the governor was permitting abuse to continue at the prisons. It turned out that the skeletal remains exhumed at Tucker Prison were those of prisoners who died of natural causes years earlier but whose bodies were not claimed by relatives. (The film Brubaker is very loosely based on Murton’s 1969 book, Accomplices to the Crime.) Nonetheless, Rockefeller achieved substantial prison reform during his tenure, including medical care, better food, an educational program, and staffing by hired guards rather than “trusties.”

On April 7, 1968, Rockefeller held a public ceremony of mourning for the death of Martin Luther King Jr. He was the only Southern governor to do so, which likely helped Little Rock escape some of the rioting that broke out elsewhere after King’s assassination.

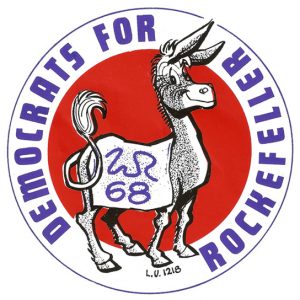

Rockefeller went into the 1968 gubernatorial campaign with a strong organization and a solid list of accomplishments. Nevertheless, there was no guarantee he would triumph. Arkansas Democrats were presented with an unusual array of characters, with Justice Jim Johnson taking on U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright, while his wife, Virginia Johnson, ran for governor. Ultimately, state representative Marion Crank received the Democratic gubernatorial nomination, though Crank was badly tainted by his long association with Governor Faubus.

In November 1968, Arkansas voters cast votes in ways that defy easy explanation. Rockefeller, a Republican, was reelected as governor—again with a huge black majority compensating for a lukewarm reception among white voters. A Democrat retained the U.S. Senate seat, with Fulbright leading the ticket in Arkansas. George Wallace, of the American Independent Party, won the presidential vote in Arkansas. No political party, it seemed, could take Arkansas for granted. Also in 1968, Rockefeller garnered eighteen votes at the Republican National Convention, but the Republican presidential nomination went to Richard Nixon. Rockefeller’s brother Nelson had made a more serious presidential run but was also unsuccessful.

Rockefeller’s second term as governor was filled with conflict with the Democrat-dominated legislature. Conflict was most severe on the issue of implementing tax reform and raising tax rates. Rockefeller mounted a campaign under the name “Arkansas is Worth Paying For,” but he accomplished little.

Along with growing unhappiness with Rockefeller’s political agenda was a rise in public realization that Rockefeller had a drinking problem. Even the dissolution of the Rockefeller marriage took place in public, with Jeannette Rockefeller slapping her husband in public on one occasion.

Still, Rockefeller filed for another term as governor, despite his traditional promise not to serve more than two terms. Rockefeller had little opposition in the Republican primary, but a raft of well-known Democrats filed for the office—including Attorney General Joe Purcell, former governor Faubus, and a little-known lawyer from Franklin County, Dale Bumpers. Untainted by previous political experience and blessed by a bright smile and a fresh vitality, Bumpers won the Democratic nomination in a runoff. In November, Bumpers defeated Rockefeller in a landslide: 375,648 to 197,418. Rockefeller was badly hurt by his defeat, and he gradually withdrew from politics. He divorced his second wife in 1971.

Much of Rockefeller’s legislative agenda was adopted by Bumpers, including the plan to reorganize state government management from hundreds of disparate agencies into a small group of departments.

Rockefeller died of pancreatic cancer on February 22, 1973, in Palm Springs, California, where he had gone to escape the cold weather at Winrock. His ashes were buried atop Petit Jean Mountain. In death, Winthrop Rockefeller continues to have an impact on Arkansas. His great wealth was divided between a charitable trust and the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, which concentrates on economic development, education, as well as economic, racial, and social justice. His son, Winthrop Paul Rockefeller, was elected Arkansas lieutenant governor in 1996. Winthrop Rockefeller was inducted into the Arkansas Aviation Hall of Fame in 1995.

For additional information:

Blair, Diane, and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2d ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Hathorn, Billy B. “Friendly Rivalry: Winthrop Rockefeller Challenges Orval Faubus in 1964.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Winter 1994): 446–473.

Jones, Merrill Anway. “A Rhetorical Study of Winthrop Rockefeller’s Political Speeches, 1964–1971.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1984.

Kirk, John. “A Southern Road Less Traveled: The 1966 Arkansas Gubernatorial Election and (Winthrop) Rockefeller Republicanism in Dixie.” In Painting Dixie Red: When, Where, Why, and How the South Became Republican, edited by Glenn Feldman. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

———. Winthrop Rockefeller: From New Yorker to Arkansawyer, 1912–1956. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Urwin, Cathy K. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–1971. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Urwin, Cathy Kunzinger. “Nobless Oblige and Practical Politics: Winthrop Rockefeller and the Civil Rights Movement.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Spring 1995): 30–52.

Ward, John. The Arkansas Rockefeller. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.

———. Winthrop Rockefeller, Philanthropist: A Life of Change. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2004.

Winthrop Rockefeller Papers. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Tom W. Dillard

University of Arkansas Libraries

This article was well written. Our government had a big heart and cared so much for the children of Arkansas. I, a child in the sixties, was one of the recipients of his kindness. I WILL ALWAYS REMEMBER HIM.