calsfoundation@cals.org

Frank Durward White (1933–2003)

Forty-first Governor (1981–1983)

Frank Durward White was best recognized as the little-known Republican candidate who defeated Bill Clinton in 1980 after Clinton had served only one term as governor. White himself was limited to one term when Clinton reclaimed the office of governor in 1982. Though his tenure in office was marked mostly by his support of teaching “creation science” in schools, White later became the grand old father of the Grand Old Party (GOP), known for his expansive sense of humor and his ability to relate to people of all political leanings.

Born on June 4, 1933, in Texarkana, Texas, to Durward Frank Kyle and Ida Bottoms Clark Kyle, White was given the name Durward Frank Kyle Jr. His father died when he was seven, and his mother later married Loftin E. White of Dallas, Texas. After his stepfather adopted him, he legally changed his name to Frank Durward White.

White attended Highland Park High School in Dallas until his stepfather died in 1950 and his mother moved back to Texarkana. He then enrolled in New Mexico Military Institute in Roswell, New Mexico. After a brief time at Texas A&M University, he accepted an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy. He graduated in 1956, ranked 273 in a class of 681. His favorite subject was Spanish, but he earned the obligatory engineering degree.

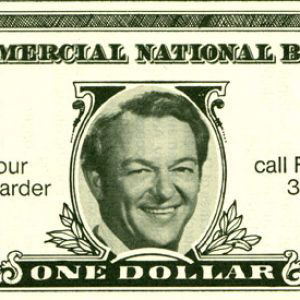

White was commissioned in the U.S. Air Force, where he served as a pilot. He was discharged in 1961 with the rank of captain. He then married Mary Blue Hollenberg of Little Rock (Pulaski County). The Whites settled in Little Rock, where the Hollenberg family was well known in the business and cultural community. White took a job at Merrill-Lynch & Co., where his gregarious personality helped him excel. In 1973, at the urging of prominent banker Bill Bowen, White joined the management of Commercial National Bank. Bowen, a Democrat who would later oppose White politically, was White’s Sunday school teacher. Despite their political differences, White and Bowen had a lasting business relationship.

White threw himself into Little Rock’s business and social life. He served as president of the Little Rock Jaycees in 1965–1966. He was active in Campus Crusade for Christ and served on the board of Arkansas Children’s Hospital. Though he was outwardly secular, religion was important to White. He grew up in the Baptist church and was baptized as a youth in the Beech Street Baptist Church in Texarkana (Miller County), later pastored by Reverend Mike Huckabee, who also became a Republican governor of Arkansas. White and his first wife divorced in 1973, and he married Gay Daniels, a devout Christian, in 1975. They had no children, but they gained custody of White’s three children from his first marriage.

The Whites were members of First Methodist Church, a historic and progressive congregation in downtown Little Rock. The increasingly liberal theology of the Methodist church did not suit White, and, in 1977, the Whites and a few other couples established Fellowship Bible Church, a conservative congregation which adhered to the inerrancy of scripture. It quickly grew in size and political influence. White’s religious beliefs later profoundly influenced his tenure as governor.

White’s first foray into state government was as a member of popular Democratic governor David Pryor’s cabinet. In 1975, White was named director of the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission (now the Arkansas Economic Development Commission). It was a perfect post for White, mixing his two loves: politics and business. But White’s tenure came during a time of economic retrenchment, and his directorship left a mixed legacy.

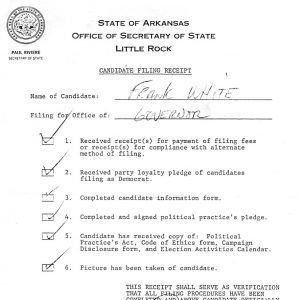

After two years at the commission, White left state government in 1977 to become president of Capital Savings and Loan Co. in Little Rock. His interest in politics was growing, and in 1980, he filed as a Republican to run against Governor Clinton, who was seeking a second term. It was assumed that Clinton would win handily, because his only Democratic opponent was an eccentric turkey farmer named Monroe Schwarzlose—and White was hardly known outside Little Rock business circles.

But the 1980 election did not go according to script. First, Schwarzlose won a respectable thirty-one percent in the Democratic primary, which should have served as a wake-up call for Clinton. Then White began airing hard-hitting television advertisements that attacked Clinton on two disparate but volatile issues—car tags and Cubans. Clinton had raised the automobile license fees to fund highway construction. The Cuban issue arose when the federal government sent several thousand Cuban refugees to a resettlement center at Fort Chaffee near Fort Smith (Sebastian County). The resulting discord at Fort Chaffee, White claimed, was due to Clinton’s failure to stand up to President Jimmy Carter, an unpopular Democrat.

White beat Clinton 435,684 to 403,242. White got off to a rough start as governor by innocently proclaiming that his election was “a victory for the Lord,” a statement that drew a chorus of criticism. Having not been considered a serious candidate until the end of the campaign, White entered office without a detailed legislative program. No sooner was he sworn in than he had to begin dealing with a looming revenue shortfall of $80 million. White drew on the expertise of two of the handful of Republicans in the legislature, Representatives Carolyn Pollan of Fort Smith and Preston Bynum of Siloam Springs (Benton County). White was philosophically opposed to raising taxes, so he had little in the way of fiscal alternatives other than cutting budgets. The situation was made worse by the hard economic times and by the severe Federal retrenchment inaugurated by newly elected President Ronald Reagan. White closed the state’s office in Washington DC, saving $600,000. He also cut the governor’s staff by twenty-five percent.

White did locate enough funding to start a vocational-technical education division in the Department of Education and increase funding for the Department of Correction. He also reformed the state’s purchasing system and worked tirelessly in pursuit of capital investment in the state—with some success when $530.8 million was reported.

Just as “Cubans and car tags” were the defining issues of the first Clinton administration, “creation science” and utility regulation were the great debates of White’s administration. Act 590 of 1981 required schools to give “balanced treatment” to “creation science” and “evolution science.” Though the bill did not originate within the administration, White promised to sign it if it fared well in the Arkansas General Assembly. When it passed handily in both houses, White signed the bill—without reading it, as he admitted later. The ensuing firestorm of criticism grew in intensity when Democratic state Senator James L. Holsted of North Little Rock (Pulaski County) admitted that he did not consult with the Department of Education or the attorney general before introducing his bill. Holsted also admitted that “we legislators have prejudices and beliefs that affect what legislation we introduce.” White defended his support of the legislation, though he noted that no governor can read every bill he signs. Arkansas Gazette cartoonist George Fisher forever after drew White holding a half-eaten banana. The court case challenging the law, McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education, brought national attention to the state, which lost the case and did not appeal.

Another issue that left a lasting imprint on the White administration involved charges that he was beholden to the large utility companies. On inauguration day, White fired the top three leaders in the Department of Energy; he later abolished the department.

During White’s reelection campaign, rumors spread that he had given power company leaders a list of prospective appointees to the Public Service Commission, which had regulatory authority over all utility companies. Detractors charged that White had given the power companies veto power over potential nominees, a charge the governor denied vigorously. White tried to shore up his standing as a utility regulator by calling a special legislative session to consider utility regulatory reform. Though his detractors charged that his efforts were half-hearted, he secured passage of laws to prohibit “pancaking,” a practice that allowed additional rate increase requests while earlier requests were pending.

The 1982 gubernatorial election was no repeat of 1980. Clinton was now the outsider, and White was busy defending his record. White also irritated part of his Republican constituency by naming former Democratic governor Orval Faubus head of the state Office of Veterans Affairs. Clinton, who had gone through personal and psychological trauma after his 1980 defeat, was not on the defensive. Clinton brought in an old political acquaintance from Texas, Betsey Wright, to organize his political campaign, and Wright was a tough political operative.

The campaign witnessed Clinton’s transformation into an effective hardball politician. Whenever White unleashed an attack, Clinton responded in kind. Clinton also understood the importance of having a sense of vision. In addition, White was hurt by a national economic downturn and rising unemployment, as well as Clinton tying him to the Grand Gulf Affair, another energy-related scandal. When the votes were counted, Clinton had a majority of almost fifty-five percent.

Though Clinton returned to the governorship in January 1983, he was not the same governor he had been the first time. Gone were the young, idealistic associates of his first administration. The new Clinton was more tentative and cautious. He came to terms with corporate Arkansas. Never again as governor would he raise his voice against clear-cutting timber companies or polluting corporate agriculture. Perhaps that transformation was White’s major impact on Arkansas politics.

White walked away from his defeat with a smile on his face but still bitten by the political bug. After brief employment with Stephens, Inc., the investment banking firm, White made a final run for governor in 1986, losing badly to Clinton. He then became an executive at Commercial National Bank in Little Rock. In 1998, Governor Mike Huckabee appointed White to the position of State Banking Commissioner, a post he filled with enthusiasm and acclaim until his death.

White also established himself as a popular toastmaster at events throughout the two decades after he retired from elective politics. He raised millions of dollars for charities and was an engaging speaker and a master of self-deprecating humor.

White died on May 21, 2003, of a heart attack in Little Rock. He is buried at Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Blair, Diane, and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government. 2nd ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Brown, Robert L. “Frank White: Arkansas’ ‘Gruff Gus’ in the Governor’s Seat.” Arkansas Times, June 1981, pp. 60–66.

Curtis Finch Jr.’s Frank White Gubernatorial Campaign Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Frank White Papers (UALR.MS.0003). Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Miller, Brian Stanford. “Car Tags and Cubans: Bill Clinton, Frank White, and Arkansas’ Return to Conservatism.” PhD diss., University of Mississippi, 2006.

Tom W. Dillard

University of Arkansas Libraries

Commercial National Bank Flyer Featuring Frank White

Commercial National Bank Flyer Featuring Frank White  First Commercial Ribbon Cutting

First Commercial Ribbon Cutting  Five Arkansas Governors

Five Arkansas Governors  Ford Visit

Ford Visit  Governors' Reunion; 1986

Governors' Reunion; 1986  Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White

Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White  Old Guard Home Parody

Old Guard Home Parody  Terri Utley and Frank White

Terri Utley and Frank White  Frank White

Frank White  Frank White

Frank White  Frank and Gay White

Frank and Gay White  Frank White Campaign

Frank White Campaign  Frank White Pin

Frank White Pin  George Bush with Gay and Frank White

George Bush with Gay and Frank White  Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form

Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form

Governor Frank White lowered taxes, cut the price of car tag renewals by one half, reduced the size of the Governor’s office staff, gave Arkansas State Police and state employees a 2% pay raise, appointed the first woman to the Public Service Commission, increased funding for vocational/technical education, appointed a woman as Director of the Department of Human Services, and cut the size of state government while still delivering the same services. He also began a yearly Governor’s Prayer Breakfast to pray for our state and nation. He did all this with a legislature composed of 140 Democrats and 6 Republicans.