calsfoundation@cals.org

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

A century of French and Spanish imperial control had little permanent effect on Arkansas, leaving it with fewer than 500 European-born inhabitants when it became part of the United States. The most significant change of the eighteenth century had been the decimation of the Quapaw Indian population, which ended the period only slightly more numerous than did the white settlers who had always been their friends and allies. Even after the Louisiana Purchase, change came slowly. Arkansas became a separate territory in 1819, but not until the 1830s did it begin to grow rapidly, a process that led to statehood in 1836. By that time, it was becoming a distinctly Southern state, the production of cotton and the institution slavery emerging as characteristics of its lowland region in the south and east. An increasing prosperity in the next several decades was destroyed by the Civil War.

Origins and Boundaries

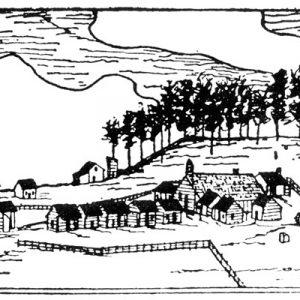

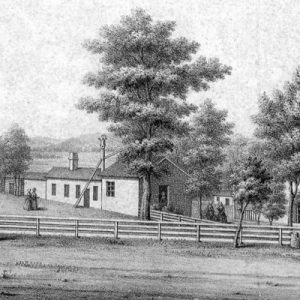

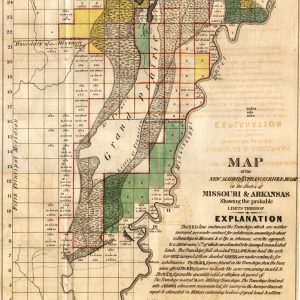

The United States Senate approved the purchase of Louisiana on October 31, 1803, and France officially gave up possession in New Orleans on December 20. Not until March 23, 1804, however, did Army Lieutenant James Many arrive at Arkansas Post to take control of the fort and village in the name of his government. Three days later, on March 26, Congress divided Louisiana along the thirty-third parallel, the present boundary between Arkansas and Louisiana, and created the Territory of Orleans in the south and the District of Louisiana in the north. As part of the District of Louisiana, Arkansas came under the administrative authority of Indiana Territory, which operated from its capital at Vincennes. This arrangement ended on March 2, 1805, when the District of Louisiana became Louisiana Territory, with a capital at St. Louis. The first official use of the name Arkansas came in 1806, when the southern portion of New Madrid County in Louisiana Territory was designated as the District of Arkansas. In 1813, it became Arkansas County in Missouri Territory. A few years later, when Missouri applied for statehood, it asked for a southern boundary at 36º30′, except for a small portion between the St. Francis River and the Mississippi River where it dropped to 36º (a portion of land known as the Missouri Bootheel). This became the northern boundary of Arkansas Territory, which was created by Congress on March 2, 1819, and included all the land running south to Louisiana and west to the Rocky Mountains. A treaty with the Choctaw Indians in 1824 defined the present western boundary from the Mexican border to Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and one with the Cherokee in 1828 resulted in a line from Fort Smith north to Missouri. After Texas entered the Union, Miller County, south of the Red River in the extreme southwest, seceded from Arkansas and joined the newer state. Arkansas Post was the territorial capital until June 1, 1821, when the government moved to the site of Little Rock (Pulaski County), also on the Arkansas River but in the center of the territory, which has remained the capital of Arkansas to the present.

Native Americans

Relatively few Native Americans lived in Arkansas when it became part of the United States. The once-numerous Quapaw, whose villages were near the mouth of the Arkansas River and who had been friends and allies of the French and Spanish colonials, had fewer than 700 people. The Caddo people, who lived along the Red River in the southwest, had moved from Arkansas south into Louisiana. Osage hunters came into northwestern Arkansas, but many of them were from villages on the Osage River in Missouri. A smaller group of Osage lived between the Neosho and Verdigris rivers, not far from where they flowed into the Arkansas River, a location now in Oklahoma but part of the original Arkansas Territory.

The most significant Indians in territorial Arkansas were the Western Cherokee, who had left their homes in the East and voluntarily migrated to the lower St. Francis River valley. At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, they numbered only about 500. Many more came within a few years, prompted by internal divisions among the eastern Cherokee and by President Thomas Jefferson, who offered them land between the Arkansas and White rivers. Around the time of the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812, they left the St. Francis River valley and settled along the Arkansas River in the vicinity of Russellville (Pope County). They built homes, cleared fields, and developed a flourishing society that may have numbered as many as 5,000 people by 1819. They also engaged in sporadic but intense warfare with the Osage, which finally ended in the early 1820s, in part because the U.S. Army outpost known as Fort Smith, created in 1818 at the mouth of the Poteau River, allowed the federal government to play a peace-keeping role.

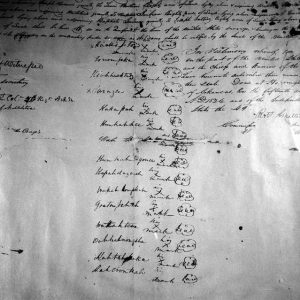

In 1824, the Western Cherokee set up a government separate from the Cherokee Nation in the East. Among their leaders were Tahlonteskee, Takatoka, and John Jolly. Sequoyah moved to Arkansas about 1822, shortly after developing his famous syllabary, which first won acceptance among the Arkansas Cherokee. In a treaty of 1817, the Western Cherokee exchanged land in the east for a permanent home north of the Arkansas River and west of a line from Morrilton (Conway County) to Batesville (Independence County). In 1828, however, pressure from the territorial government of Arkansas led to another treaty by which the Cherokee gave up their claims in Arkansas and moved across the border into Indian Territory.

By a treaty in 1818, the Quapaw gave up their claims to a vast area running west between the Arkansas and Red rivers and accepted title to an area bounded by the Arkansas, Ouachita, and Saline rivers that extended from Arkansas Post to the edge of what would soon become the territorial capital at Little Rock. White settlers wanted to grow cotton on that land, however, and the United States forced the Quapaw to accept a new treaty in 1825 that sent them to join the Caddo people along the Red River in Louisiana. Few Choctaw ever lived in Arkansas, but they were granted a large portion of its southwest in 1820, only to be moved further west in 1825. Many Quapaw returned to Arkansas, though, remaining until an additional treaty in 1833 removed them to the Indian Territory, which later would become the state of Oklahoma.

Settlement

Post-colonial Arkansas in 1803 had perhaps 500 white inhabitants, most of them of French descent, living along the Mississippi River and the lower portions of the Arkansas and White rivers. Some of them were American citizens who had begun to trickle in during the 1790s, and their numbers increased when the land became part of the United States. The American settlement of Arkansas, however, did not begin in earnest until after the War of 1812, due, in part, to land grants given to veterans of the war. The Census of 1810 covered only eastern Arkansas, and there were some new settlers in the central and northern parts of the area, but the total white population and their small number of slaves was probably not too much over the official count of 1,062 people.

Meanwhile, however, scientist and planter William Dunbar and physician George Hunter led a party of soldiers up the Ouachita River to Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1804 and 1805. President Jefferson had promoted the expedition, which was originally supposed to explore the southwestern portion of the Louisiana Purchase in the same way Lewis and Clark did the northwest. The danger of attack by the Osage on the Arkansas River led Hunter and Dunbar to undertake a much shorter journey, which nonetheless provided Congress with its first scientific report on Louisiana.

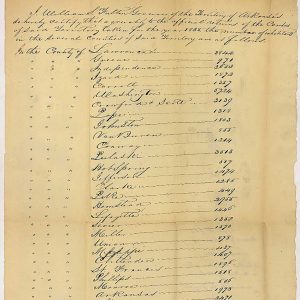

The first significant American settlement of Arkansas came from the southeast portion of rapidly growing Missouri, where, by 1810, settlers were already moving down the Southwest Trail that ran diagonally from Cape Girardeau to the Red River. Over the next decade, this migration increased and left settlements at Batesville and its vicinity, Cadron (Faulkner County) and other places on the Arkansas River, various points on the upper Ouachita River and its tributaries, and in the Red River bottom land. As a result, the population center of Arkansas shifted well to the west of Arkansas Post, and the influence of the French settlers in the east rapidly declined. The growth was hardly spectacular, however. The Census of 1820, which covered the entire territory (but excluded the Cherokee), found only 14,273 people. In 1830, there were 30,388.

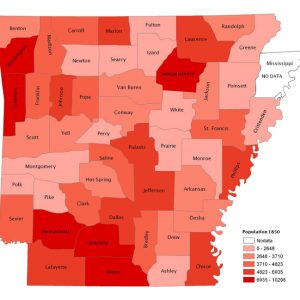

Arkansas’s population grew rapidly during the 1830s as massive numbers of Americans moved to all parts of the West. An 1835 census listed 52,240 people, and the number jumped to 97,974 in 1840. It doubled to 209,987 in 1850 and then doubled again to 435,450 in 1860. Nonetheless, Arkansas in 1860 still had only eight people per square mile and was barely out of its frontier stage. The early American immigration to Arkansas included large numbers of people from Kentucky and Tennessee, and those states continued to be important sources of settlers. With the growth of the cotton kingdom, however, an increasing number of new settlers came from the Deep South. In 1840, a majority of the white population of Arkansas lived in the highland areas of the north and west, but by 1860, about sixty percent were in the cotton-growing lowlands of the south and east.

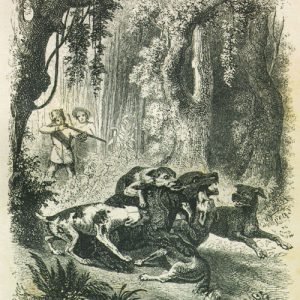

The most numerous European-born people that came to Arkansas were from Germany. Most of them immigrated alone or in families, but 130 people associated with an immigrant society arrived as a group in Little Rock in 1833. The Census of 1860 enumerated 736 native-born Germans in Arkansas, one large community in and around Pulaski County and another at Long Prairie, south of Fort Smith. Friedrich Gerstäcker, a German visitor to the United States, hunted and traveled in Arkansas from 1838 to 1842 and wrote an account of his adventures that is a major source of information on the state in that period. There were also several hundred German Jewish merchants living in Little Rock, Camden (Ouachita County), and Helena (Phillips County) by the time of the Civil War.

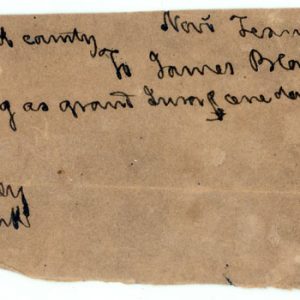

Throughout the period, new settlers were eager to acquire land, and most of the older residents wanted to increase their holdings. The earliest titles grew out of Spanish grants given to early settlers in the eastern part of the state prior to the Louisiana Purchase. These had to be confirmed by the United States, a process that was difficult at first but became easier over time. Several settlers, such as Sylvanus Phillips, for whom Phillips County is named, received approximately 2,000 acres, and well over 100 claimants got smaller amounts. In all, the Spanish grants put about 100 square miles of land into private ownership, much of it on questionable documentation. The survey of public land in Arkansas began with the creation in 1815 of an initial survey point for all land west of the Mississippi River. The point was located at the intersection of one line surveyed north from the mouth of the Arkansas River and another line west from the mouth of the St. Francis River. Lee, Phillips, and Monroe counties come together today at that survey point, now Louisiana Purchase Historic State Park.

Land sales began at Little Rock and Batesville in 1822, and officers were later located at Fayetteville (Washington County), Washington (Hempstead County), and Helena. Standard purchase procedures were supplemented by a number of special programs that benefited small farmers and speculators alike. Congress gave certificates to people who had lost land as a result of the New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812, allowing them to select acreage in other parts of the territory and take title free of charge. Or they could sell their rights to others—usually land speculators. The federal government also provided grants of land, known as Cherokee Donations, to individuals who claimed to have lost land when the Cherokee boundary was created in 1828, while the state likewise offered land to settlers through the Arkansas State Donation Law of 1840. As a result of the Swamp Lands Act of 1850, the state received several million acres from the federal government in return for carrying out drainage programs and building levees, and much of this land was sold at low prices. Manufactured evidence and other forms of fraudulent activity connected with these laws brought many more acres into private hands than would otherwise have been the case. Land speculators made large amounts of money, but settlers still usually found acreage at prices that were less than the federal government charged. Many settlers also took advantage of preemption to squat on federal land and avoid both the cost of buying it and the taxes associated with ownership. In 1840, well over a majority of the families in the state were squatters.

Agriculture and Economics

The economic basis for the earliest Anglo-American settlement of Arkansas was hunting and subsistence farming. By 1819, however, the potential for commercial agriculture was drawing people into the territory. Along with the rest of the Mississippi Valley, Arkansas benefited from the growth of a market economy based on improvements in transportation. In 1822, a steamboat arrived at Little Rock, and within a few years, steamboats were operating on all the larger rivers of the state. River transportation was vital because Arkansas had few improved roads.

By 1840, an emerging plantation society existed in the southern and eastern part of the territory, particularly in the bottom lands of the Arkansas, Mississippi, Ouachita, and Red rivers. Cotton was becoming an important commercial crop, and small farms in the highland areas grew a variety of crops, including wheat, oats, and tobacco. All over the state, farmers grew corn and raised livestock, the latter with little attention to providing shelter or breeding selectively. The average Arkansan owned more livestock, particularly hogs, than his counterpart in Missouri or Tennessee, and per capita production of corn was roughly the same in Arkansas as in those states.

From 1840 to 1860, the per capita production of cotton rose from fourteen bales to eighty-four bales, a sixfold increase compared to the fourfold growth in population. Even in 1860, planters were only three percent of all taxpayers, and the owners of fewer than twenty slaves, most of whom had only one or two, were only seventeen percent. Nonetheless, southern and eastern Arkansas became the frontier of the cotton kingdom of the South. Chicot County in the southeastern corner of the state was much like the Deep South. In 1860, its eighty planters owned an average of fifty-eight slaves and 1,800 acres of land and made up nineteen percent of the households. Slaves were seventy-eight percent of the population in Chicot County in 1860. Other plantation counties included Phillips, Jefferson, Union, and Lafayette.

In addition to agriculture, the Arkansas economy included commercial activity, most of it associated with supplying the residents with imported manufactured goods, including clothing, home furnishings, and foodstuffs not available locally. Arkansas was overwhelmingly rural, but there were urban areas of political and commercial significance. Little Rock was the largest with a population of fewer than 4,000 in 1860. Others were Fayetteville, the center of government in heavily populated Washington County in the northwestern corner of the state, Batesville on the White River in the north-central region, Washington in the southwest, Camden in the south-central, Helena on the Mississippi River, and Van Buren (Crawford County) on the upper Arkansas River. Other than a textile factory built in Pike County on the eve of the Civil War, there was no large-scale manufacturing. But local artisans produced a variety of products, including furniture, guns, and fine silver. One of the first makers of what came to be called the bowie knife was James Black, a blacksmith in the town of Washington. Tanneries, distilleries, and sawmills were among the facilities that processed Arkansas products.

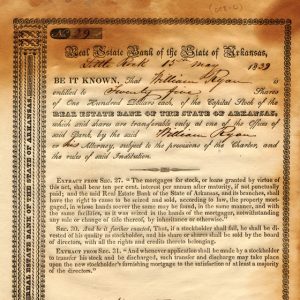

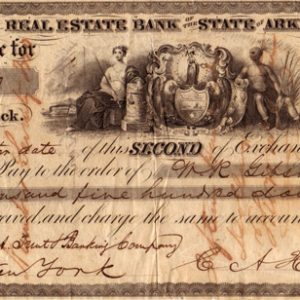

Shortly after statehood, legislators—most of them planters—created two banks (the Arkansas State Bank and the Arkansas Real Estate Bank) that were designed to generate capital for agricultural expansion by selling state-backed bonds secured with land, crops, and improvements. It was an unsound plan, badly administered, and the banks opened just as the Panic of 1837 threw the nation into a major depression. They went out of business, and the state was left with a huge debt that it refused to pay.

Politics

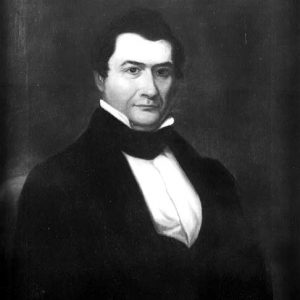

The earliest political leaders in Arkansas were men whose eastern political connections gained them access to territorial offices. The initial territorial secretary, Kentucky’s Robert Crittenden (who arrived at Arkansas Post well before the first governor, James Miller), quickly moved to set up a territorial government and make himself into a power broker. Within a few years, however, his faction was overthrown by a small group of interconnected people known appropriately as “The Family,” or “The Dynasty.”

Their origins lay in the nepotism of William Rector, surveyor general of Missouri Territory, who provided public jobs in newly created Arkansas Territory for five of his brothers and two of his cousins. One of his cousins, Henry W. Conway, began the Family’s political dominance by being elected territorial delegate in 1823. A defining event occurred in 1827 when Secretary Crittenden shot and killed Delegate Conway in a duel that grew out of a recent election. Ambrose Sevier—Conway’s cousin and the son of the renowned Kentucky Indian fighter, John Sevier—was elected delegate and served for the rest of the territorial years. He also married the daughter of Benjamin Johnson, who was justice of the Superior Court of the territory (later the Supreme Court of Arkansas) and brother of Richard Mentor Johnson (hero of the War of 1812 and later Martin Van Buren’s vice president). For a good portion of the antebellum period, the Family faction also included William Woodruff, who provided political advice and the editorial support of the Arkansas Gazette, and wealthy attorney and land speculator Chester Ashley.

Territorial Arkansas was administered by a series of relatively effective territorial governors. The first of these, James Miller, played an important role in working out a peaceful solution between the Osage and the Cherokee. George Izard exercised a much more effective control over state government than did Miller. John Pope was largely responsible for the building of a handsome (and still-standing) capitol (now known as the Old State House), and William Fulton, albeit somewhat unwillingly, led the territory into statehood, after which he was selected to serve as a U.S. senator.

Because the Missouri Compromise mandated that a new slave state had to be paired with a free state, Arkansas rushed to join the Union at the same time as Michigan. After a complicated legislative struggle, Congress created the state of Arkansas on June 15, 1836, and state government began on September 13. The state constitution was much like those of other recently formed Southern states, implementing suffrage for free, white men and providing ironclad support for slavery.

During the statehood period, the Family continued to dominate Arkansas politics as the leaders of the Jacksonian Democratic Party. Two of the late Henry W. Conway’s brothers, James Sevier and Elias N. Conway, served as governors of the state. Ambrose Sevier was a U.S. senator from 1836 to 1848, and Benjamin Johnson’s son, Robert H. Johnson (Sevier’s brother-in-law), served as a U.S. congressman from 1847 to 1853 and a U.S. senator from 1853 to 1861. Chester Ashley also served in the Senate. Archibald Yell, a friend of President Andrew Jackson, became a federal judge in northwestern Arkansas and was probably the state’s most popular politician. He was elected governor and then congressman with Family support, serving in the latter position until he died leading a charge at the Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican War. The only successful anti-Family politician was Thomas C. Hindman, who moved to eastern Arkansas from Mississippi, opened one newspaper in Helena and another in Little Rock to support his positions, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1858, and put together a faction that defeated the Family candidate for governor in 1860.

Arkansas had a Whig Party, led in part by Albert Pike, who published the Arkansas Advocate, the editorial opponent of the Democratic-leaning Arkansas Gazette. The Whigs put up a spirited opposition to the Democrats, but no Whig candidate for governor, U.S. Congress, or president ever won more than forty-five percent of the popular vote, and none was sent to the Senate.

State elections usually revolved around personalities rather than issues. Partisans demonstrated a great deal of enthusiasm in pseudonymous essays in the press, and candidates engaged in the boisterous campaigning of the period. Both parties supported the economic opportunity that could make a farmer into a slaveholder and a slaveholder into a planter. Aside from the disastrous experiment with banking, the Democrats did little to address the problem of internal transportation and failed to create an effective system of public education. Support for the institution of slavery was strong, although less so in the highlands (the Ozark and Ouachita mountains) than in the lowlands (the Arkansas Delta and the Gulf Coastal Plain). There was some sectional hostility between owners of small farms in the highlands and the lowland planters, which was particularly evident during the process of creating a state constitution. For the most part, however, the planters dominated state government with the support of the yeoman-farmer majority and the artisans, businessmen, and professionals. All of these groups shared most of the planters’ economic interests and hoped to emulate their success. When North-South sectionalism became bitter, Arkansas never wavered from its regional loyalty. Political enemies Robert W. Johnson and Hindman both adamantly supported slavery and Southern nationalism. The northwest counties required some convincing on the issue of secession, but a largely united Arkansas left the Union along with the rest of the upper South after the Battle of Fort Sumter.

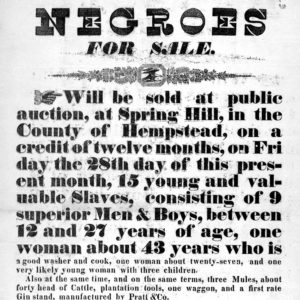

Slavery

Slaves made up only thirteen percent of the American population in eastern Arkansas in 1810, and that dropped to eleven percent in 1820 because most of the early settlers were hunters and subsistence farmers. During the controversy over slavery that led to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Congress came close to prohibiting the institution in the newly-created Arkansas Territory but failed to do so. The number of slaves on the U.S. Census for the state grew to fifteen percent in 1830 and twenty percent a decade later. Between 1840 and 1860, it rose from twenty percent to twenty-six percent, still well below the fifty-five percent for the South as a whole. Ninety percent of slaves lived in the lowlands. In Lafayette County and Chicot County on the eve of the Civil War, the Black population was more than seventy percent.

Enslaved people appear to have lived much as they did in other parts of the South, although Arkansas slaves, like their owners, were almost all migrants and had often traveled considerable distances to get where they were. Their treatment varied greatly depending on their owners, but most probably had food, clothing, and housing that was not much worse than what poor laborers had in the North. On the other hand, their birthrate was significantly lower and mortality rate higher than those of white people. They were subject to severe punishment, and brutal whipping was not uncommon. Running away, often for short distances and brief periods of time, was a relatively common form of resistance that could lead to punishment but also improvements in treatment and working conditions. The slave family was an important institution, despite the predatory sexual behavior of some slave owners. The Black culture of music, dance, and folktales also flourished where slaves lived together on plantations. Plantations represented less than ten percent of slave-holding units but were home to nearly fifty percent of enslaved people. There was a large slave population in Little Rock that functioned as artisans and house servants. While less than one in five slaves were members of white Christian denominations, Black Christianity was an important aspect of slave culture.

Society and Culture

Aside from politics, the leading cultural interest of Arkansans was religion. Methodists were in the majority in the early years, but Baptists were catching up fast by the Civil War. There were a significant number of Presbyterians but far less than either of the first two, and they were increasing at a rate well below the population growth rate. These groups identified with and promoted the evangelicalism that was the dominant form of worship throughout the South. Disciples of Christ were also present in significant numbers. There were probably fewer Episcopalians and Roman Catholics, but their traditions were important elements of the religious culture.

Women were as important to the development of Arkansas as men were, although they were in a minority well into the statehood period. Presumably responding to the economic opportunity provided by Arkansas land and the need for laborers, they had children at a rate higher than in any other state or territory. They worked hard, often at manual labor, and took responsibility for farms and even plantations when their husbands were absent. They were often lonely, missing the support of family and friends they had left behind. Black women endured a special burden of slavery, raising children who were valuable property to their masters and subject to being sold or taken away.

Early Arkansas had a reputation for violence, lawlessness, and economic indolence. Some basis for that came from the Western and frontier quality of the territory that attracted rough men and provided cover for the criminally inclined. Southerners also brought a strong sense of honor that required men to respond violently when insulted, and the competition for political office led to dueling and also less-regulated combat, such as when John Wilson, speaker of the Arkansas House of Representatives, stabbed Representative J. J. Anthony to death during a legislative debate in 1837. Less spectacular forms of violence were common, and men routinely carried bowie knives, sometimes called Arkansas toothpicks, and pistols on the streets of Little Rock.

The reputation for economic backwardness was supported by the large number of poor squatters and yeoman farmers. The still-developing plantation economy left many planters living much like their poorer neighbors. There were few antebellum mansions in Arkansas. Economic inequality, however, was as severe as almost any place in the United States, with ten percent of households owning seventy percent of taxable wealth. There was some reality to the stereotype of the indolent but charming squatter of the “Arkansas Traveler” painting, but that perspective ought to be balanced by the value of Arkansas property in 1860, mostly land and slaves, which gave it a per capita wealth that ranked Arkansas sixteenth among the thirty-four states in the Union.

Conclusion

In one sense, Arkansas was a work in progress when its development was interrupted by the Civil War. For example, its population was twice as large in 1860 as it had been in 1850. On the other hand, the shape of its society and culture was clear. The geographic difference between the mountain areas of the north and west and the lowlands of Mississippi Delta and the south had created one society of small farms and another that contained enough of plantation culture to exercise economic and political leadership. In an unrecognized struggle between the influence of the American frontier and that of the South, the latter had won, and it determined the destiny of the state.

For additional information:

Bolton, Charles S. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

———. Territorial Ambition: Land and Society in Arkansas: 1800–1840. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Brown, Carl E. “Improving the Way to the Land of Opportunity: Internal Improvements in Antebellum Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2012. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/549/ (accessed August 30, 2023).

Brown, Walter Lee. A Life of Albert Pike. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Cash, John David. Tales of the Arkansas Frontier: Territorial and Early Statehood Eras. Edited by Frank Thurmond. Marion, MI: Parkhurst Brothers Publishers, 2025.

DuVal, Kathleen. “Choosing Enemies: The Prospects for an Anti-American Alliance in the Louisiana Territory.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Autumn 2003): 233–252.

———. “Debating Identity, Sovereignty, and Civilization: The Arkansas Valley after the Louisiana Purchase.” Journal of the Early Republic 26 (Spring 2006): 25–59.

Gerstaecker, Friedrich. Wild Sports in the Far West. Introduction and notes by Edna L. Steeves and Harrison R. Steeves. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1968.

Maley, John, and F. Andrew Dowdy, ed. Wanderer on the Frontier: The Travels of John Maley, 1808–1813. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2018.

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Milson, Andrew J. Arkansas Travelers: Geographies of Exploration and Perception, 1804–1834. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Moore, William Waddy. “Territorial Arkansas.” Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, 1963.

Nuttall, Thomas. A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory During the Year 1819. Edited by Savoie Lottinville. Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1980.

Ross, Margaret J. Arkansas Gazette: The Early Years, 1819–1866. Little Rock: Arkansas Gazette Foundation, 1969.

Schuette, Shirley. “Strangers to the Land: The German Presence in Nineteenth Century Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2005.

Smith, David A. “Preparing the Arkansas Wilderness for Settlement: Public Land Survey Administration, 1802–1836.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Winter 2012): 381–406.

Stokes, Dewey Jr. “Public Affairs in Arkansas.” Ph.D. diss., University of Texas, 1966.

Toudji, Sonia. “Women in Early Frontier Arkansas: ‘They Did All the Work Except Hunting.’” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

White, Lonnie J. Politics on the Southwestern Frontier: Arkansas Territory, 1819–1836. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1964

Williams, Leonard. Cavorting on the Devil’s Fork: The Pete Whetstone Letters of C.F. M Noland. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1979.

Wilm, Julius. Settlers as Conquerors: Free Land Policy in Antebellum America. Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2018.

Woods, James M. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

S. Charles Bolton

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.