calsfoundation@cals.org

James Black (1800–1872)

James Black, popularly known as the maker of the bowie knife, was one of the early pioneers of Arkansas and settled in the town of Washington (Hempstead County) in southwest Arkansas.

James Black was born on May 1, 1800, in New Jersey; the names of his parents are unknown. His mother died when he was young, and his father remarried. Black did not get along well with his stepmother and ran away from home at the age of eight to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. While in Philadelphia, he was taken in as an apprentice to a silverplater named Stephen Henderson. During that time, Black apparently became strongly skilled in the art of silverplating. In 1818, when he was eighteen years old, his apprenticeship expired.

After completing his apprenticeship, Black went to the new territories of the United States west of the Mississippi River. He first settled at Bayou Sara (West Feliciana Parish), Louisiana, on the Mississippi River and set up a blacksmith shop. Some think that Black met Jim Bowie for the first time here in 1822. In late 1823, after battling disease and major floods, Black decided to move. He went up the Red River to Fulton (Hempstead County) and settled in the vicinity of Washington.

Around 1824, Black was hired by local blacksmith William Shaw. While working for Shaw, Black made a reputation for himself in the community as a skilled craftsman and blacksmith, and Shaw offered to make Black a partner in his business. Shaw had nine children; the eldest daughter was Anne, age sixteen. Black and Anne Shaw fell in love, but her father objected to the relationship, and Black decided to move from Washington to western Arkansas Territory.

Black settled on the Rolling Fork River that flows into Little River just west of the territorial settlement of Paraclifta (Sevier County). He set up a dam on a portion of the river and established a grist mill along with a blacksmith shop. James and Gilbert Clark also settled in the same vicinity with him and set up a salt works. Not long after they were settled, the U.S. government declared that the land they settled was part of Indian Territory and not in the territory of Arkansas. Black, the Clark brothers, and other settlers had to move to other lands. Black decided to move back to Washington.

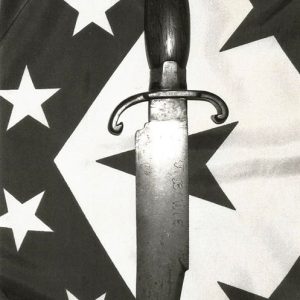

Black had not forgotten Anne Shaw, and on June 29, 1828, they were married at the Hempstead County Courthouse in Washington without the consent of William Shaw. They were married for seven years and had five children. Black opened his own blacksmith shop and prospered, becoming well known for the quality of his knives and his use of silver plating. In late 1831, Black claimed to have made a knife for Jim Bowie. An article in the Washington (Arkansas) Telegraph on December 8, 1841, attributed the forging of the knife for Jim Bowie to him.

Tragedy soon hit the Black family. His wife died on September 12, 1835. Not long after her death, while Black was at home recovering from a fever, William Shaw severely beat him. It was said that Shaw’s dislike for Black had increased due to Black’s popularity as a skilled blacksmith and his marriage to Shaw’s daughter without Shaw’s consent. Black lost the majority of his eyesight as a result of the fever and the attack. He then left the area to visit doctors who could possibly help his eyesight in Cincinnati, Ohio, and New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1836, while Black was away, Shaw was declared the guardian of Black, his family, and all of his estate. In 1840, property owned by Black was sold, and, in 1841, Shaw took custody of Black’s children. That same year, Black was declared a pauper by Hempstead County.

Following this, Black lived with Jacob and John Buzzard for a short time at their plantation on the Red River in what is now Miller County. In 1842, Black was taken into the care of Dr. Isaac Newton Jones and his family at Washington. Black ultimately lost his eyesight and suffered dementia. One of the sons of Dr. Jones was future Arkansas governor Daniel Webster Jones. After the Civil War, Black spent his final years at the home of Daniel Webster Jones in Washington. On May 1, 1870, Black tried to recall to Jones the secret method of how he made his knives but was unable to remember the process. Jones noted that Black rubbed his forehead until it began to bleed, finally crying out, “My God! My God! It has all gone from me!”

On June 21, 1872, Black died at the residence of Jones. According to Jones, he was buried in the old graveyard, Pioneer Cemetery, of Washington. Newspapers as far away as Memphis, Tennessee, commented on his death.

For additional information:

“The Bowie Knife.” Washington Telegraph. December 8, 1841, p. 2.

Rains, Ray D. The Tragic Punishment of James Black and Other True Stories about Arkansas and the Deep South. Pangburn, AR: Little Red River Journal, 1981.

Williams, Charlean Moss, The Old Town Speaks: Recollections of Washington Hempstead County, Arkansas: Gateway to Texas, 1835, Confederate Capital, 1863. Houston, TX: Anson Jones Press, 1951.

Joshua Williams

Historic Washington State Park

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

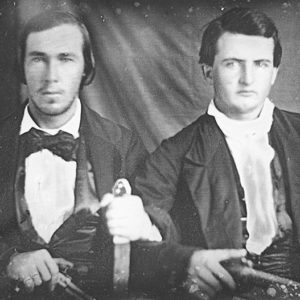

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 James Black & Jacob Buzzard

James Black & Jacob Buzzard  James Black's Home

James Black's Home  Bowie Knife

Bowie Knife  Bowie Knife

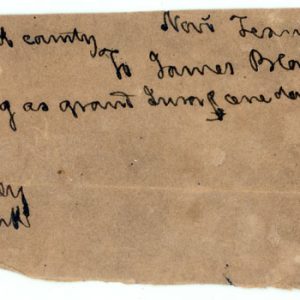

Bowie Knife  Grand Jury Receipt

Grand Jury Receipt

James Batson’s book James Black and His Coffin Bowie Knives is almost certainly the definitive book on the subject.