calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas's Image

Two defining forces have shaped Arkansas’s image. First, physical geography placed the Mississippi River floodplain on the state’s eastern border. Second, public policy determined that, for almost 100 years, the region adjacent to the state’s western border would be known as Indian Territory. The combination of these two forces were primarily responsible for Arkansas being less densely populated than its neighboring states and being predominantly rural for the first 150 years of its existence as a territory and state. Given that Arkansas lacked a major urban area or dominant physical attraction, relatively few people had first-person knowledge of the state. As a result, this area came to be viewed as a rustic, backwoods region out of touch with mainstream America.

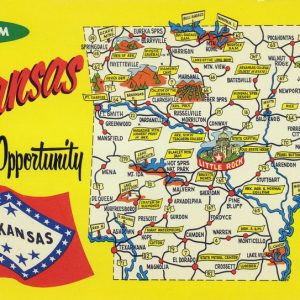

In an effort to overcome its negative image, Arkansans have tried on four different occasions to establish an image appropriate for economic growth and development. For most of the nineteenth century and first two decades of the twentieth century, Arkansas was the Bear State. In the decades between World War I and World War II, it was the Wonder State. From the early 1950s through the mid-1980s, it was the Land of Opportunity, and since 1987, Arkansas has been the Natural State.

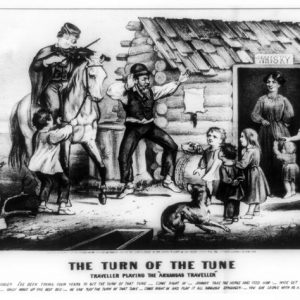

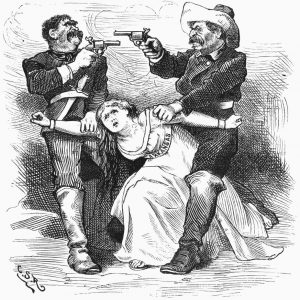

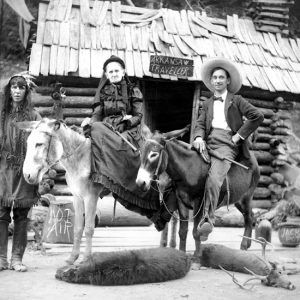

The Bear State, although never officially adopted as a nickname by the General Assembly, characterized Arkansas as a sportsman’s paradise, with bear hunting the pinnacle of a hunter’s experience. This image emphasized the wild and less civilized aspects of the state’s development. Physical violence occurred frequently among the state’s inhabitants, typically young and male, and visitors commented more often about these confrontations than the region’s fledgling churches, schools, and political parties. This image was solidified by the writings of German adventurer Friedrich Gerstäcker, who traveled the state in the 1830s and described his experiences in a German publication translated as Wild Sports in the Far West. Charles Fenton Mercer Noland, an Arkansan contemporary to Gerstäcker, described the rustic backwoods culture of the Ozark uplands to East Coast audiences in a New York publication called “The Spirit of the Times.” Publicity from those writings led Massachusetts-born Thomas Bangs Thorpe to write a short story about “The Big Bear of Arkansas” in the 1840s. A decade later, local artist Edward Payson Washbourne gave a final touch to the rustic image with a painting titled the “Arkansas Traveler.” The canvas depicted a buckskin-clad, native settler in dialogue with a smartly dressed “stranger” outside the settler’s crudely built log cabin.

Arkansas’s early acceptance of slavery and association with the bowie knife also contributed to its negative image. The popular hunting knife, also known as the “Arkansas Toothpick,” was widely manufactured in numerous locations ranging from Washington (Hempstead County) to Sheffield, England. The violence associated with the knife found its way into many characterizations of the state’s reputation, including the writings of Herman Melville and Charles Dickens. Closer to home, the widely publicized fatal stabbing of Representative Joseph J. Anthony by Speaker John Wilson—which occurred in the House chamber while the state legislature was in session—gave added evidence for the state’s violent and negative image.

By the time of the Civil War, the state’s image was entrenched as what historian S. Charles Bolton called a “remote and restless” region. Bypassed by the major migration routes to the West Coast, Arkansas had the smallest population in the Mississippi River Valley. It was little known to outsiders, beyond the writings and the painting mentioned above. Even though, as Bolton has pointed out, the state’s agricultural production ranked above regional averages, the antebellum image of Arkansas remained that of an underdeveloped region.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, various Arkansans worked to change the Bear State image. In an effort to present an image that would attract economic investment, Little Rock (Pulaski County) real estate developer Theodore B. Mills refocused Washbourne’s painting to feature the “stranger” rather than the “settler.” Mills arranged with officials of the St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad Company to bring a number of journalists to the state. Providing lavish entertainment and a steady supply of promotional data, Mills achieved his objective when the short-lived celebrities returned to their home newspapers and wrote glowing articles about the state’s potential for investors. Mills collected these “reports” and published them in a booklet titled “The New Arkansas Traveler.” Rather than rustic and backwoods, Mills’s Arkansas was a prime location for economic development and a vital part of the emerging New South movement.

State officials and other private businessmen tried to complement Mills’s efforts to cast the state in a more positive light. Using a series of exhibits for display at various world fairs and expositions around the nation, these leaders tried to present the state at its best. At the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, Arkansas cotton won first place for “the best in the bale.” At the Louisville Industrial Exposition in 1883, Arkansas won first place for cotton and also added a blue ribbon for the best apples in the exposition. In 1893, Chicago led the nation in commemorating Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the new world by hosting a massive Exposition and World’s Fair. Arkansas entries won more than fifty awards and were observed by more than six million people. A final exposition came in 1904 when St. Louis organized a world’s fair to memorialize the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. Arkansas was again recognized for the quality and diversity of its products. Success at the world fairs, even though most awards were for agricultural and forestry products, did help the state overcome some of its backward image.

Ironically, even as state and business leaders promoted a more positive image of Arkansas, other forces were at work that had the effect of neutralizing much of the favorable publicity. For example, a popular theatrical production featuring Kit, the “Arkansas Traveler,” opened in theaters in 1869. The title character was a rustic, homespun rube with a distinct regional dialect. The play continued in production until 1899 and was performed to nationwide audiences; Kit did much to offset the image of the “New Arkansas Traveler.”

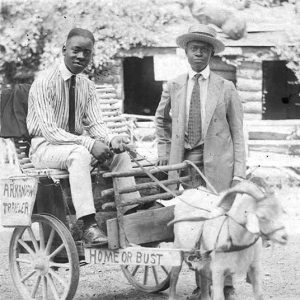

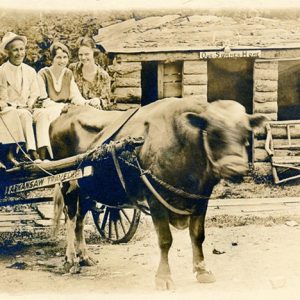

Journalist Opie Read reinforced the theatrical production depiction. In 1882, he began writing a column titled “The Arkansas Traveler” for a local newspaper. Set in a rural enviroment, with “hillbillies” providing “creacker barrel” wisecracks as they discussed the issues of the day, Read depicted Arkansans as being provincial and unconcerned about the outside world. Many of his humorous stories were printed in a periodical called the Arkansaw Traveler. The various remakings and retellings of the Arkansas Traveler story led William H. Edmunds, a spokesman for the railroad interest in the state, to publish a booster tract, “The Truth about Arkansas,” in 1896 in which he concluded that the Traveler image had cost the state millions of dollars by the end of the nineteenth century.

Isaac Parker was another individual who, albeit unintentionally, helped negate much of the positive publicity generated in the late nineteenth century. Parker was appointed federal judge in 1875 for the state’s Western District, which consisted primarily of Indian Territory. Over the next twenty years, he earned a national reputation as the “hanging judge” by sentencing over 150 individuals to the gallows. The trials and public executions were widely publicized in the national press.

Arkansas’s backwoods reputation was cemented in 1903 when Thomas Jackson published a joke book titled On a Slow Train Through Arkansaw. The jokes made the state and residents the object of ridicule and went through multiple reprints. It was common reading in most train depots throughout the Southwest and all but erased the positive image Mills and other business leaders had attempted to create.

The Wonder State image emerged after World War I. Former governor Charles H. Brough led in organizing the Arkansas Advancement Association, a community of leading businessmen who sought to improve the state’s image and attract economic investment. In 1923, the Association persuaded the General Assembly to adopt formally the Wonder State as the state’s official nickname. In so doing, the legislators noted that the Bear State image was no longer appropriate for the new era. Promoting the image, Brough made numerous speeches touting the state’s resources and investment opportunities. In the spirit of promoting the “wonders” (e.g., vast collections of minerals, rich soil, and extensive forests) of the state, Brough gave Arkansas one of its most enduring images—self-sufficiency. He pointed out that the region’s resources were so diverse that “if a fence was built around Arkansas,” the state would be self-sufficient.

Brough’s skill as a public speaker made him one of the most popular attractions on the Chautauqua lecture circuit. He carried his positive image of Arkansas to thousands of Americans in the Midwestern and Southern regions. Ironically, even as he worked to promote the state, other forces were at work that neutralized his efforts. Henry Louis (H. L.) Mencken, a journalist based in Baltimore, Maryland, was the first to suggest an alternative view about the state. In a seven-page article about the South as a region, Mencken included a brief reference to Arkansas, including the statement that residents of the state were “too stupid to see what was the matter with them.” The Arkansas General Assembly passed a resolution demanding that Mencken apologize for his negative reference to the state but, in doing so, misspelled the writer’s name. Mencken responded by making Arkansas the subject of a series of articles, and instead being the subject of two sentences buried in a lengthy article about a region, the state became a singular focus for negative comments. The impact of such unfavorable publicity was compounded by the fact that Mencken’s readership was primarily among well-to-do Easterners, the group that Brough and others had been encouraging to invest in the Wonder State.

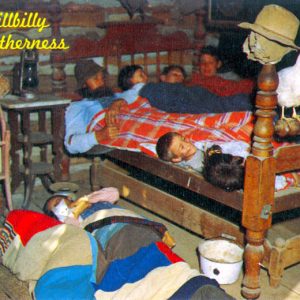

The Wonder State image received more setbacks in the 1930s. In 1931, two residents of Mena (Polk County), Chester Lauck and Norris Goff, created the mythical characters Lum Eddards and Abner Peabody. Lum and Abner used the language, jokes, and philosophical musings of the Arkansas hill country to launch a radio program known as the Lum and Abner show. The team was an immediate success, and three months after the first program aired in Hot Springs (Garland County), the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) signed Lauck and Norris to a contract and moved the show to Chicago, Illinois. For the next twenty-five years, millions of Americans were entertained by these “rural philosophers” who operated from their “Jot ’Em Down Store” to dispense political commentary, sage advice, and earthy humor to a nation struggling with the Great Depression. Although a commercial success, the show reinforced the hillbilly, backwoods image reminiscent of the Bear State. Lum and Abner also performed in vaudeville and made seven motion pictures before being eclipsed by the new medium of television in 1953.

Robin Burns of Van Buren (Crawford County), working under the stage name of Bob Burns and also known as the Arkansas Traveler, added to the Arkansas’s backward image. A contemporary with Chester Lauck and Norris Goff, Burns used similar fanciful yarns and slapstick humor about kinfolk and friends in Arkansas as he performed on radio, in the movies, and with the big bands of the 1930s and 1940s. By the end of World War II, Burns, along with Lum and Abner, had succeeded in thoroughly characterizing Arkansas as an undeveloped region, disconnected from mainstream America. The hillbilly image of Arkansas had been so ingrained to the rest of the nation that the widely popular Reader’s Digest reprinted a note posted on a closed defense plant bulletin board—“Pair of shoes for sale, moving back to Arkansas.”

In the mid-1940s, a group of Little Rock businessmen became concerned about the failure of the Wonder State promotion and the negative images associated with Burns and Lum and Abner. Led by Hamilton Moses, head of Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), and aided by a group known as the Committee of 100, this group sought to promote economic development and stop the flow of many of the state’s most productive citizens leaving the state. Changing the state’s image became an essential part of the group’s plan. Abandoning the Wonder State label, Moses and his friends chose “Land of Opportunity” as the new nickname and began an intensive campaign to promote Arkansas. In 1953, the General Assembly made the new image official. But the new image-makers discovered that old images were hard to overcome. In 1954, the American Mercury, one of H. L. Mencken’s former publications, wrote, “Arkansas stands for watermelons, the unshaven Arkie, the moonshiner, slow trains, malnutrition, mental debility, hookworm, hogs, shoelessness, illiteracy, windy politicians, and hillbillies.” To the Committee of 100, which was working to recruit major corporations to the state, the quote was a challenge to overcome.

The same year the Mercury article appeared, state voters elected Orval Faubus as governor, and he, in turn, appointed Winthrop Rockefeller to lead the state’s economic development. For a brief time, Rockefeller was highly successful in persuading new companies to move to Arkansas. In his first year of recruiting, over 600 new industrial plants established operations in the state. However, during his second year as head of the state’s industrial recruiting, the Central High School desegregation crisis erupted, and the state was subjected to a new round of negative publicity. World attention was focused on the city and state’s response to integrating its largest high school. No new industrial plants opened in Little Rock, or the surrounding Pulaski County, for a full year after the crisis. Moreover, Rockefeller resigned from the industrial development commission, and the state again struggled with its image.

Damage to the state’s Land of Opportunity image continued in the 1960s. In the middle of that decade, the state prison system came under scrutiny and was described by one writer as comparable to “the Nazi death camps.” That charge, coupled with an Arkansas State Police investigation of the facilities, caused a committee of the U.S. Congress to hold hearings on the state’s treatment of prisoners and attracted national media attention. The collective reports characterized Arkansas’s prison system as dark and barbaric—filled with torture (as with the “Tucker Telephone“), sadism, and murder— and became the subject matter for the Hollywood-produced movie Brubaker (1980). In addition, the U.S. Supreme Court case of Epperson v. Arkansas, which challenged the state’s ban on teaching evolutionary theory, cast Arkansas in a poor light when the Court easily dispensed with state arguments. (The specter of creationism would rise again with the 1981 McLean v. Arkansas case.)

The state’s image began to improve in the 1970s. Rapidly increasing population on the East and West coasts, coupled with retirements in the workforce and changes in the national economy, caused thousands of Americans to relocate to less densely populated regions with seasonal climates. Arkansas became a magnet state during this “Sunbelt movement” and, for over a decade, was second only to Florida in the percentage of its population over age sixty-five, with numerous communities developed focusing upon retirees. Tourism also became an increasing part of the state’s economy and, by 1977, was the third largest industry in Arkansas.

To capitalize on the new demographics and the shift in the nation’s economic emphasis, several individuals sought ways to establish a new identity for the state. Led by the Department of Parks and Tourism, officials began to emphasize the state’s unpolluted air, fresh water, green forest, fish, and wildlife in promotional materials. In 1987, the Arkansas General Assembly officially dropped the Land of Opportunity and replaced it with “The Natural State.” The new image was readily accepted by most Arkansans and reconnected them to the outdoor environment of the Bear State.

Ironically, as Arkansans comfortably settled in to the Natural State image, new circumstances developed that confused the state’s new look. In 1992, native son William Jefferson Clinton launched the first of two successful campaigns for president, and for almost a decade, an international press corps examined most every aspect of the state’s heritage. The old problem of lacking an identity was overcome when this extraordinary amount of attention made Arkansas a familiar location around the world. However, the state was typically characterized as an underdeveloped region with an “incestuous” political tradition, especially during the investigation of the Whitewater scandal.

That reputation was reinforced by the highly publicized trials of three teenagers for the 1993 murders of three children in West Memphis (Crittenden County). Prosecutors linked the crime to Satanic practices allegedly practiced by the accused and won their convictions, but a national backlash ensued due to the claim and the state’s lack of physical evidence. In 2011, after intense legal battles financed by supporters around the world, the men who had become known as the West Memphis Three were abruptly and unconditionally freed from prison—one from a sentence of death, and the other two from terms of life—after they signed a rare plea agreement in which they admitted guilt for the murders while maintaining that they were innocent.

The growing influence of retail giants Walmart Inc. and Tyson Foods, among others, drew thousands of service workers to the state and led to an airport capable of servicing the nation’s largest aircraft and a four-lane express way being built in the state’s scenic Ozark hill country. By the twenty-first century, in the words of historian Ben Johnson, Arkansas had cast off much of its rustic image and now “looked [more] like America.” This remote region of the nineteenth century had become incorporated into the national mainstream of trade and commerce. While hillbillies and slow trains may always be a part of the state’s legacy, that image is rapidly evolving to include businessmen in corporate jets. However, the rise of online news sources and social media has presented a challenge to the state. For example, beginning in 2013, a series of billboards widely viewed as racist was erected in Harrison (Boone County), a city whose history includes early twentieth-century race riots in which all but one African American was expelled. Likewise, in early 2015, the state government’s practice of celebrating the state holiday honoring Robert E. Lee, a Confederate general, on the same day as the federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day made the national news in the light of one state legislator’s failed attempt to separate the two holidays (this was finally accomplished two years later).

Such events, and the ease with which news about them can be rapidly and widely spread, often serve to reinforce the state’s historical image within the larger national culture. But stereotypes about Arkansas also remain part of the cultural mainstream. In 2014, the Discovery Channel aired Clash of the Ozarks, a six-episode “reality television” series set in Arkansas that reinforced the image of feuding hillbillies. Too, official state actions can still reinforce Arkansas’s “backward” image, as happened when Governor Asa Hutchinson scheduled eight executions within an eleven-day period, beginning the day after Easter in 2017, based upon the imminent expiration of one of the state’s lethal injection drugs. The perceived “rush” of executions (four of which were actually carried out) attracted negative headlines the world over.

In 2021, the actions of the Arkansas General Assembly and Gov. Hutchinson attracted repeated attention to the state of Arkansas in such a way as to reinforce many of the negative aspects of Arkansas’s image. The Republican-dominated legislature debated multiple bills restricting and even outlawing abortion, limiting the activities and medical treatment options of transgender youth (a first-of-its kind bill soon copied by other Republican-led states), outlawing the teaching or promotion of “divisive concepts” (especially as relates to the history of racism in the state and nation), restricting voting rights, and more; one bill would have even legalized the teaching of creationism in state schools. Several of these bills passed the legislature and were signed into law by Gov. Hutchinson. National and even international media reported on these bills, with even Swedish Radio (Sverigesradio), for example, devoting coverage to the law rendering most abortions in the state illegal, even when pregnancies were the result of rape or incest. Meanwhile, an attempt to pass a genuine hate crimes bill in the state stalled completely due to the inclusion of groups defined by sexual orientation and identity. In addition, ongoing legislative resistance to efforts to mitigate the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with a vaccination rate near the bottom of the United States, also shaped how Arkansas was perceived in the world at large.

Arkansas continued to attract negative local and national headlines even after the pandemic began to recede. In 2023, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the daughter of former governor Mike Huckabee and the former press secretary for President Donald Trump, signed into law Act 195, eliminating the requirement that minors under the age of sixteen verify their age and receive the written consent of a parent or guardian before being employed. Many national publications lamented the growing acceptance of child labor in conservative circles; for example, a March 26, 2023, New York Times editorial stated, “Arkansas is at the vanguard of a concerted effort by business lobbyists and Republican legislators to roll back federal and state regulations that have been in place for decades to protect children from abuse.” Sanders’s signing of the bill came after Packers Sanitation Services, a food sanitation company with facilities in Arkansas, was fined for employing children between ages thirteen and seventeen in hazardous conditions.

For additional information:

Arkansas/Arkansaw: A State & Its Reputation. Old State House Museum Online Collections. Arkansas/Arkansaw Collection (accessed July 15, 2021).

Blevins, Brooks. Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, and Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Cash, John David. “Fent Noland, Thomas Bangs Thorpe, and Friedrich Gerstaecker: Positive Images of Frontier Arkansas.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 51 (April 2020): 3–10.

Cochran, Robert B. “‘Low, Degrading Scoundrels’: George W. Featherstonhaugh’s Contribution to the Bad Name of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 3–16.

Cottingham, Jan. “Arkansas and the Last Taboo: It’s a Class Thing.” Arkansas Times, June 26, 1998, pp. 11–13.

Dew, Lee A. “‘On a Slow Train Through Arkansas’—The Negative Image of Arkansas in the Early Twentieth Century.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Summer 1980): 125–135.

Dougan, Michael B. “Bumpkins and Bigots: The Arkansas Image in Fiction.” Publications of the Arkansas Philological Association 1 (Summer 1975): 5–15.

Friedlander, E. J. “‘The Miasmatic Jungles’: Reactions to H. L. Mencken’s 1921 Attack on Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Spring 1979): 63–71.

Gwaltney, Francis Irby. “What It Means to Be an Arkansan.” Arkansas Times, September 1977, 16–20.

Howell, Elmo. “Mark Twain’s Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Autumn 1970): 195–208.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in the Modern South since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Lancaster, Bob. “Bare Feet and Slow Trains.” Arkansas Times, June 1987, 34–41, 88, 90, 92–94, 96–98, 100–101.

———. “No Match for Mencken.” Arkansas Times, April 19, 1996, p. 13.

Lisenby, Foy. “A Survey of Arkansas’s Image Problem.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Spring 1971): 60–71.

———. “Talking Arkansas Up: The Wonder State in the Twentieth Century.” Mid-South Folklore 6 (Winter 1978): 85–92.

———. “Winthrop Rockefeller and the Arkansas Image.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43 (Summer 1984): 143–152.

Milson, Andrew J. Arkansas Travelers: Geographies of Exploration and Perception, 1804–1834. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Noland, C. F. M. Cavorting on the Devil’s Fork: The Pete Whetstone Letters of C. F. M. Noland. Edited by Leonard Williams. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

Otto, John Solomon. “‘On a Slow Train Through Arkansaw’: Creating an Image for a Mountain State.” Appalachia Journal 14 (Fall 1986): 70–74.

Potts, Monica. The Forgotten Girls: A Memoir of Friendship and Lost Promise in Rural America. New York: Random House, 2023.

Shea, William L. “A Semi-Savage State: The Image of Arkansas in the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Winter 1989): 309–328.

Smith, Doug. “Unhand Us, You Brutes.” Arkansas Times, January 27, 1993, pp. 14–15.

Terry, Bill. “Arkansas In Search of an Image.” Arkansas Times, September 1978, pp. 36–39.

Tucker, David M. Arkansas: A People and Their Reputation. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1985.

Watkins, Patsy G. “Same People, Same Time, Same Place: Contrasting Images of Destitute Ozark Mountaineers during the Great Depression.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Autumn 2011): 288–315.

Williams, C. Fred. “The Bear State Image: Arkansas in the Nineteenth Century.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Summer 1980): 99–112.

Williams, Carmen Lanos. “Arkansas in the African American Imaginary: A Rhetoric of Place.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2019.

Worthen, William B. “Arkansas and the Toothpick State Image.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer 1994): 161–190.

C. Fred Williams

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.