calsfoundation@cals.org

Germans

German immigrants played a significant role in the development of Arkansas’s economy and in the founding of many social, religious, and cultural institutions, even though the number of German immigrants never represented more than one percent of the state’s population. Long after German immigration to the state reached its peak in 1882, evidence of the immigrants’ presence remains.

Colonial and Territorial Years through Early Statehood

As the eastern United States became more crowded, people of all backgrounds followed the transportation routes, primarily the rivers, looking for less crowded living conditions and greater opportunity; a few reached Arkansas. The censuses taken during the 1790s at Arkansas Post included fewer than ten German families, settlers who probably came from the Vincennes area of what is now Indiana.

Newspaper accounts and other documents identified Germans among the early settlers of the state. For instance, in June 1820, the Arkansas Gazette reported that Samuel Reichenbach from Switzerland had arrived at Arkansas Post looking for land for a group of immigrants. Whether such a settlement actually came about is uncertain. Also, on August 27, 1821, the Gazette published the obituary of thirty-eight-year-old Christian E. Zoeller from Emmendingen, Germany. Zoeller taught at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point before coming to Arkansas.

The 1830 federal census, while it does not list ethnicity, does indicate households that include aliens or foreign-born persons not yet naturalized. Of six such households in the state, two can be identified from other records as being German immigrants. John Heilman settled with his family near Cincinnati, Ohio, in the early 1820s and came to Arkansas around 1825, settling in what is now the Crystal Hill area of Pulaski County. In addition, Charles Fischer was in Little Rock (Pulaski County) as early as September 1826 and operated the new City Hotel and Tavern. German adventurer and author Friedrich Gerstäcker, who lived and traveled in the state between 1838 and 1842, so enjoyed the company of Fischer that he wrote a number of short stories based on his life.

A large group of German immigrants arrived in Arkansas in May 1833. They settled mostly in Pulaski and Saline counties, but a few went to Perry and White counties. This group left Germany as an organized emigration society, with plans to establish a German colony in Arkansas. Conflicts within the group led them to abandon such plans while still en route. One hundred forty followed the original plan and settled in Arkansas, forming a strong base of support for later German immigration.

Another antebellum migration pattern, repeated after the Civil War, was the influx of Jewish merchants attracted by economic opportunities. Beginning as peddlers, these immigrants opened stores and other businesses, a process critical to the economic development of the state. Although concentrated in the larger commercial areas of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Little Rock, many were also scattered around the state. Approximately 200 German Jewish merchants lived in the state at the beginning of the Civil War. More than seventy of these fought in the Confederate army.

Another concentration of immigrants developed in the pre–Civil War period on the far western edge of the state, especially in the Long Prairie community south of Fort Smith and in the town itself. The presence of a military fort on the western border of the state and the trade with the Indian tribes to the west strongly influenced this influx of immigrants. For instance, Valentine Dell, who came to America in 1846, served in the U.S. Army. He came to Fort Arbuckle in Indian Territory as a settler and then remained in the area and became a prominent Fort Smith citizen.

German individuals and families continued to come to Arkansas during the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s. Often, such immigrants came as part of a chain migration pattern, settling near a relative or a friend. For example, in 1834, John Schoppach stayed on the Pulaski County farm of his university acquaintance Wilhelm Huebsch while he looked for land. Schoppach eventually settled in Saline County, and was himself followed sometime later by a brother-in-law and eventually his nephew Frederick Busch.

The years between 1848 and 1852 saw political unrest in Germany, triggering a rise in immigration to America. Hermannsburg (later known as Dutch Mills) in Washington County was founded as a result of such immigration. John Reichardt, who left Germany because of his participation in political and revolutionary activities, settled in Arkansas in 1852. The Geyer family and the Kramer family, whose names persist today on roads, buildings, and communities in central Arkansas, also arrived during this time. The number of Germans settling in the state during the antebellum period remained modest. In 1850, the first year ethnicity is listed in the census, only 516 out of Arkansas’s population of 209,897 were identified as German born—only about 0.25 percent. Nevertheless, their diligent ways in farming and business made a positive impression on leaders of the cities and the state, so that when active recruitment of immigrants began following the Civil War, Germans were identified as being among the most desirable.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

Immigration was greatly reduced during the Civil War. Nevertheless, the size of Arkansas’s German community increased by about one-third, from 1143 in 1860 to 1,563 in 1870. Many of these newcomers were Germans who had served in the Union army in Arkansas and made the state their home.

Religious and economic factors came together with the growth of the railroads to promote immigration following the Civil War. For a time, state governments, railroad companies, and real estate agents recruited immigrants. Arkansas governor Powell Clayton talked of recruiting immigrants in his 1868 inaugural message. Intense efforts came only at the end of the 1870s, when railroad construction had progressed to the point that land was widely available in the Arkansas River Valley. German-language publications were issued touting the benefits of Arkansas, and agents were sent to German communities in the eastern United States and also to Europe to entice settlers to the state.

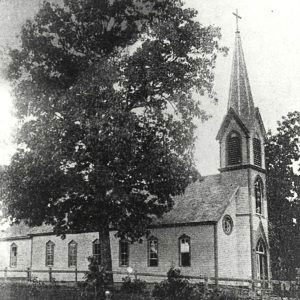

Given grants of government land, the railroads moved west, financing construction and establishing a market for their services through selling land to immigrants. Both the Lutheran and the Catholic churches, the two denominations most closely associated with the German community, cooperated with the railroads in developing German immigrant communities in Arkansas. The Catholic Church was involved in direct recruitment, acting as an agent for the railroad, while the Lutheran Church concentrated on supporting immigrants after they arrived.

With encouragement from Bishop Edward Fitzgerald of the Diocese of Little Rock, the Catholic Church entered into agreements with the railroads, setting aside land grant areas for immigrants recruited by the Church itself. Two such agreements resulted in strong areas of German settlement in the Arkansas River Valley. The Benedictine Order founded a colony based in Logan County and remained following the initial immigration period. Subiaco Abbey and Academy in Logan County remains as a monument to their work.

The Holy Ghost Fathers brought many settlers into the state, some of whom stayed and made important contributions to the economy and politics in Conway and Faulkner counties. However, the order did not itself maintain a significant presence in the state. Following a series of disasters, including a tornado in April 1883 that destroyed the Catholic church in Conway (Faulkner County) and an 1892 tornado that destroyed their monastery, the group abandoned its plans for a permanent monastery and seminary in Arkansas.

Catholic missionary Father John Eugene Weibel, after serving a congregation in Logan County, began work among the German Catholics in northeast Arkansas. Weibel arrived in Randolph County on December 1, 1879. Over the next several years, in addition to serving as priest for the church in Pocahontas (Randolph County), Weibel traveled the railroad line, preaching and conducting services among the workers at each stop. In this way, he brought many new German immigrants to the area and founded several new German Catholic congregations.

German Catholic communities developed in Jonesboro (Craighead County) and Paragould (Greene County), both centers for the growth of railroads in the area. Some German Catholics who settled in the neighboring counties, such as Lawrence and Clay, had a strong community connection to the Catholic churches that grew from Weibel’s work. Weibel and the Holy Angels Convent that he founded were instrumental in starting what is now St. Bernards Medical Center in Jonesboro.

Lutheran congregations formed in both Fort Smith and Little Rock in 1868. Each church was founded in an urban area by Germans who had been in Arkansas for a relatively long period of time. Other Lutheran churches grew out of immigration following recruitment efforts in the 1870s. Most notably, a group of German Lutherans settled on the Grand Prairie in eastern Arkansas, forming the core of the city of Stuttgart (Arkansas County). In addition, as German families bought railroad land and moved into the state, either directly from Germany or as transplants from other states, Lutheran churches were established in the Arkansas River Valley, as well as in northeast Arkansas.

The peak of German immigration in Arkansas, as in the rest of the United States, occurred in the early 1880s. At the same time that the “push factors” in Germany eased somewhat, the “pull” factors in America also weakened. Legal restrictions placed on immigration reduced the flow of newcomers, a fact that contributed to the weakening of the existing ethnic communities.

The Twentieth Century

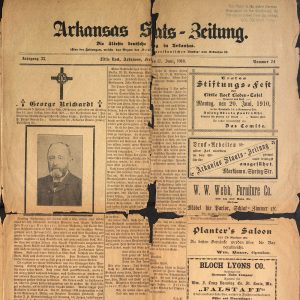

In 1900, following the strongest period of German immigration into the state, only 5,971 first-generation Germans lived in Arkansas, or 0.46 percent of the population of 1,311,564. Despite such small numbers, Germans in Arkansas retained a strong ethnic identity until the time of World War I. Both the Catholic and the Lutheran churches maintained parochial schools, often with all teaching done in German. Also strengthening the German community was the St. Joseph Society, a Catholic benevolent organization that cooperated to meet the needs of its members. Das Arkansas Echo, a German Catholic newspaper published in Little Rock, continued to appear until 1932, even as German newspapers elsewhere in the country closed due to anti-German feeling at the beginning of World War I. (The Stuttgart Germania and the Arkansas Staats-Zeitung, for example, had closed in 1914 and 1917, respectively.)

Strong differences had always existed within the community itself, based on religion, social or economic class in Germany, or the area of Germany the immigrant came from. Such differences were overcome, however, when the community faced conflict with the native-born population, especially over the question of prohibition of alcohol. Many ethnic Germans had come to the state in response to ads promoting Arkansas as perfect for growing grapes for wine. When Prohibition threatened their success, they felt strongly that the state itself had broken a promise.

Anti-German sentiment in the state was so strong with the outbreak of World War I that many parochial schools stopped teaching in German. German names for locations and businesses were changed. For instance Meyer’s Bakery became American Bakery for a time, and the community of Germania southwest of Little Rock became Vimy Ridge.

These events only hastened a shift that was well under way as early as 1910. The inevitable fading of the strong ethnic presence was demonstrated in three Arkansas German Day celebrations. Programs for the 1908 and 1909 celebrations were written in German and had essays expressing strong pro-German sentiments. The program for the 1910 German Day celebration, however, used English extensively and presented a schedule that was much more social and recreational than political.

Due to legal quotas imposed following World War I, immigration never returned to the levels it had reached in the decades after the Civil War. The pattern returned instead to that of scattered newcomers, mostly refugees or war brides. These people experienced anti-German sentiment in the community, but it occurred more in isolated incidents rather than pervasively.

Scattered groups of German-American clubs have been active since World War II, especially in Little Rock and in the Fayetteville (Washington County) area. Nevertheless, few new immigrants arrived, and members of the older immigrant families gradually assimilated into the general population. Aside from isolated examples such as the Swiss wine-producing community of Altus (Franklin County) and a continuing emphasis on German heritage in Stuttgart, by the late twentieth century, the strongest evidence of the earlier German communities was in the buildings and institutions they built, and their impact on the economy and society.

For additional information:

Assenmacher, Hugh, OSB. A Place Called Subiaco: A History of the Benedictine Monks in Arkansas. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1977.

Barnes, Ken. “‘Don’t Go to Arkansas’: How the Prussian Government Tried to Curb Emigration to the Arkansas River Valley in 1881 and 1882.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 44 (Fall 2001–Spring 2002): 9–13.

Condray, Kathleen. “Arkansas’s Bloody German Language Newspaper War of 1892.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Winter 2015): 327–351.

———. Das Arkansas Echo: A Year in the Life of Germans in the Nineteenth-Century South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Durning, Dan. “The First Turnverein (Turner Society) and the Rise of Little Rock’s Community of German Speakers.” Pulaski County Historical Review 70 (Summer 2022): 40–56.

———. “The Fischer Brothers: The St. Louis Socialist and the Haymarket Anarchist Who Founded the Arkansas Staats-Zeitung (1877–1917).” Pulaski County Historical Review 70 (Winter 2022): 116–133.

———. “The Loetschers: Early Swiss Immigrants Who Settled in Cadron Township.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 65 (Fall 2023): 7–18.

———. “Pulaski County’s Asch Emigrants: Helping Build Little Rock’s Economy, 1863–1919.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Winter 2021): 128–146.

———. “Pulaski County’s German-Bohemian Emigrants from Asch: The Geyer, Reichart, and Penzel Families, 1848–1861.” Pulaski County Historical Review 68 (Winter 2020): 100–113.

———. “Pulaski County’s German-Bohemian Emigrants from Asch: The Disruptions of the Civil War Years, 1861–1865.” Pulaski County Historical Review 69 (Spring 2021): 22–40.

———. “Those Enterprising Georges: Early German Settlers in Little Rock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 21 (June 1973): 21–37.

———. “‘The Trouble Is in Existence’: The Life and Battles of German-American Newspaperman Phillip Dietzgen.” Pulaski County Historical Review 71 (Summer 2023): 63–84.

Evans, Clarence. “Memoirs, Letters, and Diary Entries of German Settlers in Northwest Arkansas, 1853–1863.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 6 (Autumn 1947): 225–249.

Huber, Herbert, Sr., OSB, trans. “Arkansas Echo 1892–1906: An Arkansas German Language Newspaper.” Annotated bibliography, 1989. On file at the Diocese of Little Rock Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas, and at the Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Miller, James William, ed. In the Arkansas Backwoods: Tales and Sketches by Friedrich Gerstäcker. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

Schuette, Shirley. “Intolerance on the Homefront: Anti-German and Anti-Black Sentiment during the War Years and Beyond.” In To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War, edited by Michael D. Polston and Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

———. “Strangers to the Land: The German Presence in Nineteenth-Century Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2005.

Suelflow, August R. The Heart of Missouri: A History of the Western District of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, 1854–1954. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1954.

Walz, Robert Bradshaw. “Migration into Arkansas, 1834–1880.” PhD diss., University of Texas, 1958.

Watkins, Beverly. “Efforts to Encourage Immigration to Arkansas, 1865–1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Spring 1979): 32–62.

Weibel, John Eugene. Forty Years Missionary in Arkansas. Jonesboro, AR: Holy Angels Convent, 1968.

Wolfe, Jonathan James. “Background of German Immigration, Part I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Summer 1966): 151–182.

———. “Background of German Immigration, Part II.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Autumn 1966): 248–278.

———. “Background of German Immigration, Part III.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 25 (Winter 1966): 353–385.

Woods, James M. Mission and Memory: A History of the Catholic Church in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1993.

Shirley Sticht Schuette

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

I’m looking for any information about the Swiss immigrants to St. Vincent, Arkansas, just north of Morrilton, then over to Little Rock in 1882. Families Amborts and Briggelers. Traveled together from Switzerland.

My great-grand-uncle was Msg. Eugene Weibel. He brought my great-grandmother here from Switzerland to teach at one of the schools he started in Pocahontas. He had St. Bernard’s Hospital in Jonesboro, St. John’s in Hot Springs, and many others. His book is a great history of Arkansas. I learned so much about the state as well as the church and the German immigrants.

Another family of early German settlers were the Rosenbaums, who settled in the 1820s (or so) in Collegeville (Bryant) in Saline County. One of the Rosenbaum daughters, Janice Constantsia (Jane) Rosenbaum, married John Christian Heilman. They lived at what is now the intersection of MacArthur Drive (the old Conway Pike) and Crystal Hill Road. The original cabin is on display in Burns Park, which is where John Christian Heilman first lived when he came to Arkansas. Rosenbaum Lake on I-430 (at the Maumelle exit) was named for Jane’s family.

I grew up at Augsburg, near the Zion Lutheran Church. This German community between Dover and London, Arkansas, was established by several families (including my great-great-grandparents Wilhelm and Margarethe Brinkmann from Minden, Germany) in the 1870-90s. Many of the descendents of the original families still live at Augsburg.

I have a pamphlet about the 100-year history of the church and families which was written by ATU professor Earl Schrock in 1983.