calsfoundation@cals.org

United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas

The United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas is the federal trial court of record for thirty-four counties in western, south-central, and north-central Arkansas. With headquarters in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and branches in Fayetteville (Washington County), Harrison (Boone County), Texarkana (Miller County), Hot Springs (Garland County), and El Dorado (Union County), the three judges and two magistrates of the Western District under Article III, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution exercise judicial power over “all cases in law and equity, arising under [the] constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made or which shall be made.” Generally, the Western District exercises power over two broadly defined types of civil cases: those that involve a federal question (such as civil rights) and those that involve a claim or controversy in excess of $75,000 between litigants in different states or in which one litigant is a citizen of the United States and the other is of a foreign nation. The Western District also has criminal jurisdiction for matters considered crimes under the United States Code.

The Beginnings of the Court

The origins of the Western District of Arkansas lie in the westward expansion of the country in general and the early 1800s resettlement of various Native American tribes into what is now Oklahoma. In particular, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 created a situation of instability and violence in what is now eastern Oklahoma and in western Arkansas, as well as portions of Texas and Kansas, thus making the creation of the court a necessity.

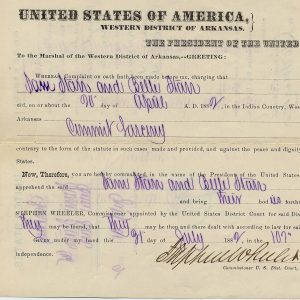

Jurisdiction over all of Arkansas and Indian Territory (as Oklahoma was then known) rested in the United States Circuit Court of Arkansas. Later rechristened the United States District Court, it sat in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and had jurisdiction over an area stretching from the northern boundary of Texas to the southern boundary of Kansas and from the Mississippi River to the 100th meridian of longitude (and, arguably, the Rocky Mountains). The jurisdiction in Oklahoma alone was more than 74,000 square miles in area. As the Arkansas Democrat noted in an editorial dated January 8, 1847, in order for a U.S. deputy marshal to enforce law in the Indian Territory, he was forced to travel 160 miles from Little Rock just to reach Indian lands and then had to travel yet another 200 miles to get to the western boundary of his jurisdiction. This was compounded by the difficulty of capturing and transporting suspects back to Little Rock, as well as serving subpoenas on pertinent witnesses. For this work, deputy marshals received the sum of two dollars per warrant and ten cents per mile of travel, from which they had to pay all their expenses. For serving a subpoena, the marshal would receive $30.50—thirty dollars for round-trip travel and fifty cents for the service of the arrest warrant.

Moreover, in the 1830s and 1840s, confusion arose over what jurisdiction was available to the District Court. Native Americans in Indian Territory had the right to enact their own system of government and justice, except in crimes that involved a non-Indian person and an Indian. The Indian nations forbade federal lawmen from leading a posse comitatus onto land given to them, forcing the marshal service to rely upon federal troops garrisoned at Fort Smith in Arkansas and Fort Wayne in Oklahoma.

During the Mexican War, when all available federal troops were fighting in Mexico, there were raids across the western boundary of Arkansas and rampant violations of the Intercourse Act, which defined what legal commerce could occur between Native Americans and whites (and, most notably, forbade the selling of alcohol to Native Americans). Additionally, a bitter and bloody internecine conflict arose between two groups of Cherokee—those who had been removed from their homes and resettled in Oklahoma under the Indian Removal Act and those who had moved voluntarily to Oklahoma beforehand. Both whites and Native Americans agitated for a court closer to the site of the problems, but President James Polk brusquely declined the request. He preferred, instead, to put one court in Indian Territory and to set strict boundaries on the tribal lands for each tribe. However, whites felt that they would not be treated fairly with Native Americans making up most, if not all, of the juries.

On June 4, 1846, U.S. senator Chester Ashley introduced a bill to divide the state of Arkansas into two judicial districts. With his untimely death, however, the bill died in the Senate. Incoming senator Ambrose Sevier did not support the bill as Ashley had. Finally, on October 9, 1850, the citizens of Van Buren (Crawford County) formulated a petition for a court in the Western District to be centered in Van Buren. The long-delayed bill was finally passed on March 3, 1851, and signed by President Millard Fillmore. Fillmore appointed George Washington Knox of Crawford County as the first marshal for the court and Jesse Turner as federal prosecutor. Judge Daniel Ringo of what had become the Eastern District of Arkansas traveled to Van Buren in May and November to preside over terms of court.

Records are spotty for these early years of the court, many having been destroyed in a fire in 1863, and no records are extant for the May term of 1851; however, it is clear that Judge Ringo proceeded rapidly to bring justice to the area. In the fall term, for instance, he sentenced an eclectic group consisting of one white, one Native American, one half-blood Cherokee, and one African American person to the gallows. A stay of execution was granted to one, Dick Benge, and it is not clear if he was ever executed. The hangings were public. The Arkansas Gazette noted that the executions would have a “salutary effect” upon the criminally inclined in the area in that they would “learn that the murder of a white man will be followed with speedy justice.”

Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Parker Era

In 1860, Judge Ringo resigned his post. There is no record indicating a national judicial presence, either Union or Confederate, in the Western District from 1860 to 1865. The next mention of the court in the historical records was an act passed on March 3, 1871, moving the federal bench from Van Buren to Fort Smith. The first term of that court was called to order on May 8, 1871, by Judge William Story in a rented building known as the Rogers Building. On November 14, 1872, fire destroyed the Rogers Building, and the court was moved to an old barracks building at the fort.

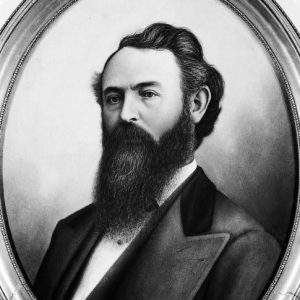

In the spring of 1874, graft and corruption had become so endemic in the Western District that Judge Story resigned, and an interim judge, Henry J. Caldwell, took the bench for a short time. In March 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed a Missouri congressman, Isaac C. Parker, to the federal bench in the Western District. Parker, something of a reformer and a champion of Native American civil rights during his congressional career, began immediately to clear the backlog of criminal cases. Before Parker took the bench, a popular saying had it that, “There is no law west of St. Louis and no God west of Fort Smith.” In 371 days, Parker sentenced fifteen people convicted of murder and rape to the gallows. During Parker’s tenure, the deputy marshals of the court became legendary and included famous Old West lawmen such as Bill Tilghman and Bass Reeves, the latter a former slave and one of the first African-American U.S. deputy marshals. They patrolled an area of 74,000 square miles, and sixty-five of “Parker’s men” were killed in the line of duty during Parker’s time on the bench.

Parker managed his court expeditiously and frugally. In 1896, a Department of Justice examiner, Leigh Chalmers, noted that the District Court for the Western District of Arkansas had the largest criminal docket in the world. In the course of the preceding year, Parker and his staff had efficiently handled more than 900 cases. It is estimated that, during his twenty-one years on the bench, Judge Parker disposed of almost 12,800 criminal cases, a rate of approximately two cases per day of service. In a more or less typical year, murders (including manslaughter) made up 11.8 percent of the cases, whereas alcohol-related crimes (untaxed liquor, selling liquor to Native Americans, and the like) made up fifty-two percent of the docket. Nor was Parker slow to punish white people who took advantage of Native Americans in Indian Territory.

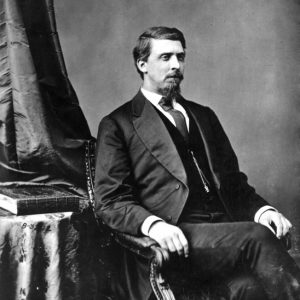

Parker was considered too favorable to the claims of Native Americans by many critics, and congressional expansionists who favored opening Indian Territory to white settlement passed legislation in 1889 that restricted Parker’s jurisdiction to the western part of Arkansas and a tiny portion of eastern Oklahoma. Congress then passed an act effective September 1, 1896, stripping him of all jurisdiction over Indian Territory, leaving the Western District roughly in its present form. Parker died later that year and was succeeded on the bench by John Henry Rogers, who held the post until his death in 1911.

The Modern Era

Although originally concerned primarily with criminal cases in its early days, the Western District court today hears a multitude of cases of varying types, both civil and criminal. In 1938, Congress authorized an additional judge to serve both the Eastern and Western districts. A second judge was added to the districts in 1961. On June 29, 1984, a temporary judgeship was authorized for the Western District which was subsequently made permanent. Today, three permanent district judges and two U.S. magistrates handle the court docket, with occasional assistance from district judges assigned to the Eastern District of Arkansas.

Criminal cases still compose a large portion of the docket, but increasingly—with the advent of the modern era of civil rights legislation coupled with the presence of such large employers as Walmart Inc. and Tyson Foods residing within the geographical confines of the Western District—employment-related matters such as discrimination in hiring and promotion, as well as employee benefits cases under Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), occupy a significant number of the cases docketed to be heard in the Western District.

For additional information:

Ball, Larry D. “Before the Hanging Judge: The Origins of the United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Autumn 1990): 199–213.

Dobbs, Byron. “A Lawyer’s Appraisal of the Parker Court.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 3 (April 1979): 27–28.

Littlefield, Daniel F., and Lonnie E. Underhill. “Fort Wayne and the Arkansas Frontier, 1838–1840.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 35 (Winter 1976): 334–359.

National Park Service Staff. “Law Enforcement for Fort Smith, 1851–1896.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 3 (April 1979): 3–6.

Tuller, Roger. ‘Let No Guilty Man Escape’: A Judicial Biography of Isaac C. Parker. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

United States District Court for the Western District of Arkansas. http://www.arwd.uscourts.gov/ (accessed April 20, 2022).

David Bowden

Little Rock, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.