calsfoundation@cals.org

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

Developments during World War II loosened Arkansas from its rural moorings as it moved toward full integration with the national economy and society. Beginning in the war years and through the 1950s, the state resumed an industrialization process that had been interrupted by the Great Depression. Arkansans migrated from the countryside to the cities and participated in the expanding consumer economy. Federal dollars subsidized infrastructure improvements. Although state political leaders welcomed the largesse from Washington DC, they resisted external pressures to acknowledge African American rights. Encouraged by ground-breaking federal court decisions, a new generation of civil rights leaders mounted direct challenges to discriminatory practices. Governor Orval Faubus responded to changing conditions with an ambitious expansion of state services, while mollifying white residents with an open defense of segregation.

Race, Class, and War

Poor health and inadequate education meant fewer Arkansans were pressed into military service during World War II. About 195,000 men served in the armed forces, although the forty-three percent rejection rate of the state’s inductees was the second highest in the nation. A far larger number of Arkansans migrated to Detroit, Michigan, and California in search of better-paying jobs in the burgeoning defense industry. At the same time, federal ordnance plants in Camden (Ouachita County), Jacksonville (Pulaski County), Maumelle (Pulaski County), Hope (Hempstead County), El Dorado (Union County), and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) (at the Pine Bluff Arsenal), as well as massive aluminum production facilities in Saline County, also enticed rural Arkansans to seek employment in either the construction or the operation of the factories.

Arkansas women seized the opportunity for new manufacturing jobs, although a smaller percentage entered the workforce than did women nationwide. Seventy-five percent of the 13,000 workers at the Arkansas Ordnance Plant in Jacksonville were female.

In addition to the more than $241 million spent to build defense enterprises, the federal government spent $100 million to establish military bases such as Camp Joseph T. Robinson near North Little Rock (Pulaski County), Camp Chaffee near Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and five training airfields in east Arkansas during the war. Residents in towns close to the camps enjoyed the profits from the influx of outsiders, and authorities generally overlooked the enforcement of regulations requiring the closing of businesses on Sunday. On the other hand, officials were unwilling to bend segregation barriers. Black and white soldiers, who occupied separate barracks on the bases, went their separate ways when on leave in Arkansas towns. Black military personnel chafed against harsh treatment. In 1942, Little Rock (Pulaski County) police officers beat and shot to death Sergeant Thomas Foster, a Black serviceman who had intervened when the officers pummeled another Black soldier. A brief investigation by local authorities exonerated the police officers, but Lucious Christopher Bates and Daisy Bates, who had recently begun publishing the Arkansas State Press, provided full details of the killing for their growing Black readership.

The incarceration of German prisoners of war at Fort Chaffee, Camp Robinson, and Camp Dermott as well as Italian POWs at Camp Monticello provoked little controversy in the state. The internment of Japanese Americans in hastily constructed camps at Rohwer (Desha County) and Jerome (Drew County) in southeastern Arkansas, however, stirred official and popular disapproval. Forced from their homes on the West Coast, most of the 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry subject to the federal relocation policy were incarcerated at sites in western states. By the end of 1942, approximately 17,000 internees lived in the Arkansas camps: Rohwer and Jerome. To pacify Governor Homer Adkins, who believed the federal government was planting an alien race in Arkansas, federal officials confined these Americans behind barbed-wire fences even as prisoners of war were dispatched to meet the labor demands of cotton farmers. In contrast to his devotion to maintaining separate spheres for whites and Blacks within Southern society, Adkins advocated complete exclusion of the relocated families. In 1943, he signed a bill to prohibit Japanese American property ownership in Arkansas. The measure was unenforceable, but few internees chose to remain in the state at war’s end.

Slow to Embrace Change

The plunging number of native agricultural workers during the 1940s did not prod landowning planters to embrace technology as quickly as would be expected. In 1934, John and Mack Rust demonstrated the first automatic cotton picker, but International Harvester took the lead in the mass production of the new machines with the hope of exploiting wartime labor shortages. Nevertheless, planters feared mechanization would provoke social turmoil among the newly unemployed workers. The relentless depopulation of the Delta compelled landowners by the 1960s to accept harvesting technology. Eventually the newly mechanized farms would dwarf the traditional plantations, and soybean and rice production would outstrip cotton in terms of acreage planted and crop value.

Rural families watching neighbors pack up for urban opportunities at least had the consolation that they were finally able to enjoy modern appliances and amenities in their rural homes. The federal Rural Electrification Administration (REA) continued the work it had started during the Depression. Half of Arkansas farms had lights by 1950.

Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), the state’s largest electrical utility, had grimly battled the REA and the federally sponsored electrical cooperatives, insisting that government subsidies should be funneled to private utilities. By the end of World War II, Hamilton Moses, AP&L’s president, began to worry less about losing rural customers and more about what the closing of the defense manufacturing plants would do to his company. His anxieties were soon eased as the government transferred properties and equipment to private concerns for a fraction of their value. Under the ownership of the Reynolds Aluminum Company, the Hurricane Creek and Jones Mills plants no longer supplied the makers of bombers and fighter planes but profited from the shift from steel to aluminum in the making of industrial and consumer goods. The withdrawal of federal defense dollars did not sidetrack Arkansas industrialization as agricultural depression and natural disasters had done during the 1920s. The number of manufacturing operations in the state in 1947 exceeded those in place at the start of the war.

Still, Moses did not want to trust the fortunes of his company to the vagaries of national economic trends. The utility’s influence over state government, its alliances with local leaders, and its impressive resources permitted the company to launch a full-scale economic development campaign that blurred the line between public and corporate interest. In the 1940s, Moses organized business leaders into the Arkansas Economic Council to advance AP&L’s plan for industrial recruitment, which in turn became the core mission of the Arkansas Resources and Development Commission, created by the legislature at the behest of Moses. In the 1950s, the Arkansas quest to lure new employers was fixed in the statutory code and constitution as local governments were permitted to finance infrastructure improvements to benefit private industries. In 1955, Winthrop Rockefeller became the first chair of the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission, a streamlined successor to the older Arkansas Resources and Development Commission.

The development boosters asserted that these initiatives had enabled Arkansas to surpass the national rate of factory growth. In truth, the food-processing and clothing plants that migrated to the state were influenced by several factors, including a ready surplus of low-wage labor. These non-durable-goods enterprises also posed fewer challenges to the status quo than the metals and chemical industries that persisted from the war era. The new plants beginning to dot the northern section of the state relied on a largely female work force that was semi-skilled and non-unionized.

Even with these new factory jobs, Arkansas women would continue to be less likely to be employed outside the home throughout the 1950s and 1960s. If American homes were crowded with more children after World War II, Arkansas mothers continued to have fewer children than the national average even though they married younger. The national divorce rate also rose, but Arkansas, as before, remained in the statistical forefront of broken marriages.

The Shift to Local Control

In a reversal of the usual economic pattern, national food giants such as Kraft, Swift, and Welch’s sold their Arkansas production facilities to Arkansas poultry companies. Buffeted by price swings, firms such as Tyson, OK Mills, and Arkansas Valley Feed pioneered a contract system with chicken producers that stabilized supplies and costs of production. The poultry industry enlisted the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) to research the breeding of a “better bird” that could be fattened rapidly. As families turned from planting row crops to producing chickens, or commuted to spend the workday on a poultry plant’s evisceration line, rural Arkansas became tethered to the national economy.

In 1952, the chicken processors formed the Arkansas Poultry Federation, which joined the utilities as a business-lobbying group expecting favorable laws and regulations from state government. Traditional Arkansas politics had been highly decentralized. Local economic elites had expected little from Little Rock other than maintaining low taxes. The new business interest groups, however, believed that a more professional and efficient government would aid economic development as well as claim a share of the revenues associated with burgeoning federal programs. Arkansas voters supported the shift from local authority and patronage politics by ratifying the 1944 constitutional amendment strengthening the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, approving a 1948 initiated act to consolidate small school districts, and assenting to another proposed amendment in 1952 to form an autonomous highway commission.

Politics and Reform

Governor Ben Laney believed that imposing business efficiency on government operations was the sort of reform consistent with his conservative philosophy. The Revenue Stabilization Act (1945) established a budget mechanism that allowed state policymakers for the first time to know for certain what money was available and how it was being spent. Laney also persuaded lawmakers to organize the Legislative Council to oversee budgets between sessions of the general assembly and to employ staff members who would relieve legislators from depending upon lobbyists to draft legislation. During the 1947 session, an infusion of young newcomers, many associated with the movement known as the GI Revolt, backed a series of measures that went beyond the usual narrow, local concerns.

Veterans in Hot Springs (Garland County) organized the first Government Improvement League, but former GI’s launched similar associations in other Arkansas communities in order to breakup the local political machines. Sidney McMath emerged as the leader of the Hot Springs GI reformers. After he gained the district prosecuting attorney’s office McMath brought to trial Leo McLaughlin, the legendary political boss of the spa city. Although McLaughlin escaped conviction, McMath’s good government reputation remained intact. In 1948, Laney did not vie for a third term, and McMath won a run-off against a candidate who campaigned as a stalwart defender of segregation.

As a racial moderate, McMath was a rare Southern politician untroubled by the civil rights initiatives set forth by President Harry Truman and national Democratic party leadership. Prominent Southern Democrats, however, resorted to secession from their party and nominated J. Strom Thurmond to run under the banner of the States’ Rights Democratic, or “Dixiecrat,” Party in order to sabotage Truman’s election. Dixiecrat leaders originally wanted Governor Laney to lead the ticket, but he preferred to mobilize the Southern dissidents within the party to prevent Truman’s nomination. McMath, bolstered by his primary victory, frustrated Laney’s attempts to stack the Arkansas delegation to the national party convention with Dixiecrats. Arkansas in November 1948 stayed with Truman, and a grateful president made a point to visit the state during McMath’s governorship.

Like Laney, McMath prized government efficiency but held that public aid and favorable treatment should be not granted only to influential business and agricultural interests. The governor promoted stiffer factory safety regulations and a higher minimum wage. He also appointed the first Black members to state boards and increased funding for the chronically under-funded Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College, the historically black college in Pine Bluff (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). McMath met a formidable adversary when he crossed swords with Hamilton Moses over the state support for a new generating station for the state electrical cooperatives. McMath launched an unprecedented highway construction program, but a highway audit commission in 1952 concluded that the administration had awarded road contracts to campaign contributors. The governor retorted that several members of the commission were allies of the AP&L chieftain. The hint of scandal—along with the opposition of U.S. Senator John L. McClellan, a law partner of Moses—doomed McMath’s bid for a third term.

The election in 1952 of Francis Cherry as governor brought to office an east Arkansas judge who adhered to old-fashioned fiscal stringency. Yet his dismissal of the elderly poor as “deadheads” and refusal to give the poultry industry a tax break played poorly with a public that expected more from government. During his run for re-election in 1954, Cherry was too politically inept to ward off the charge that he was responsible for an unpopular rate increase that the independent Public Service Commission had granted AP&L. Surprisingly to some observers, the May 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which deemed segregated schools unconstitutional, did not heat up the debate among the candidates. Cherry insisted that Arkansas would observe the law, while Faubus, his principal challenger, did not denounce the governor’s moderation. Faubus unseated Cherry, who once again misunderstood the political landscape and attempted to smear the veteran for his enrollment twenty years earlier at Commonwealth College, a radical labor school in Mena (Polk County).

Early Attempts at School Desegregation

That the Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education remained a minor issue in the campaign reflected the generally measured response by state officials to earlier civil rights rulings. When the whites-only election primary was struck down in 1944, the Arkansas Democratic Party constructed an elaborate system to limit Black voting but abandoned the effort by 1950. Although the poll tax remained in effect, its $1.00 cost rendered it a less critical obstacle. More important than the erosion of legal barriers to voting was the migration of Black citizens away from the plantations of rural oligarchs. Black voter participation grew through the mobilization efforts of the Committee on Negro Organizations, founded in 1940 by Harold Flowers. In 1948, Flowers, the preeminent Black attorney of his era, escorted Silas Hunt when he enrolled at the University of Arkansas School of Law as the first Black student admitted to a postgraduate program in the state. Gov. Laney opposed the federal court decision that opened professional schools to Black students but acquiesced after the dean of the law school explained that resistance would be futile, expensive, and self-defeating. A few months after Hunt’s admission, Edith Irby became the first Black student to enroll at the School of Medicine of the University of Arkansas.

In most Southern states following the 1954 Brown decision, political and school leaders delayed action until the Supreme Court detailed how rapidly and how extensively desegregation should proceed. Hundreds of school districts in border states such as Missouri and Kentucky, however, officially integrated. School boards in the three Arkansas districts of Charleston (Franklin County), Fayetteville (Washington County), and Sheridan (Grant County) were the first within the boundaries of the former Confederacy to vote to have Black and white students sit in the same classrooms. No incidents erupted during the first year of desegregation in Charleston or in Fayetteville, which were mountain locales with relatively few Black students. In addition, Black and white leaders in Fayetteville held community meetings prior to the opening of the school year and gained an agreement with the local newspaper to keep the news out of the headlines. Events followed a different course in Sheridan, a south Arkansas community with a larger proportion of Black citizens. One day after voting to desegregate, the school board reversed itself in the face of a forceful white backlash. Although segregation was preserved, angry speeches and threats at a subsequent mass meeting led to the resignation of all but one school board member. Soon, an exodus of Black residents, which made Sheridan a nearly all-white community, settled the matter.

In 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that school districts would not be subject to federal deadlines for desegregation but were free to determine how best to meet the vague standard of moving “with all deliberate speed.” The Court’s deference to local authority heartened the segregationist resistance movement. In the fall of 1955, leaders of groups such as the Citizens’ Council of Arkansas and White America, Inc., organized white opposition to school integration in the northeastern Arkansas town of Hoxie (Lawrence County). In contrast to the Sheridan leaders, Hoxie school board directors did not buckle despite sustained harassment and demands for their ouster at raucous public rallies. Segregationist agitators such as James Douglas “Justice Jim” Johnson and Amis Guthridge retreated when the school board secured a federal injunction banning activities that hampered the implementation of desegregation. Yet defeat at Hoxie prepared the white militants for upcoming battles against desegregation.

The Desegregation Crisis of 1957

The Little Rock school crisis of 1957 caught the city by surprise. The most significant opposition to Superintendent Virgil Blossom’s plan to enroll selected students into Central High School had been registered by Daisy Bates, president of the state chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and other African American leaders who had wanted desegregation extended to the lower grades. However, the federal district court overruled the NAACP suit filed by Wiley Branton, a protégé of Harold Flowers. Blossom assured influential figures that his plan of minimal compliance with court rulings would not provoke segregationist reprisals. The peaceful desegregation the previous year of the municipal bus system seemed to justify Blossom’s confidence.

Nevertheless, the ardent segregationists mobilized for battle. Angry that Faubus had not backed the Citizens’ Council campaign against integration in Hoxie, the segregationist Johnson challenged the incumbent governor in the 1956 Democratic Party primary. Faubus gained reelection by promising to protect segregated institutions without unleashing the disorder and extremism associated with the Johnson forces. After his defeat, Johnson welcomed the chance to force the governor to either defend segregation or accept responsibility for its demise. Lulled by Blossom’s reassurances, white civic leaders in Little Rock were unprepared to counter rising segregationist agitation.

Faubus believed that following the law spelled his political doom, and he risked open defiance of federal authority by using the state guard to prevent nine African American students from entering Central High on the first day of the 1957 school year. President Dwight Eisenhower negotiated with the Arkansas governor and believed he had persuaded Faubus to accept desegregation. This policy of accommodation fell apart when Faubus left Central High unprotected, and over a 1,000 white protestors rioted as the Black students attempted on September 23 to re-enter the school. Television cameras caught the fury of the crowd and introduced Americans across the nation to the hardening battle lines over civil rights. Eisenhower dispatched the 101st Airborne Division to enforce the court orders. Throughout the remainder of the school year, either U.S. troops or National Guard personnel accompanied the black students to school and kept watch in the halls. Segregationists mounted grassroots campaign to provoke and publicize turmoil in the school to demonstrate that desegregation was unworkable. In May 1958, Ernest Green became the first black graduate of Central High.

If Johnson took satisfaction in backing Faubus into the radical segregationist corner, he also came to understand that Faubus had displaced him as the popular champion of resistance. Faubus burnished his militant credentials by sponsoring a successful bill during a special session in 1958 that closed Little Rock high schools, subject to a local referendum. In September 1958, Little Rock voters favored keeping the schools closed to preserve them from integration. During the “lost year,” students lived with relatives to enroll in out-of-town schools, attended classes in churches, took correspondence courses, attended private schools, or just simply ended their educations. The silence of empty classrooms echoed the silence of local business and professional men. The first organization of white moderate forces was the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC), formed primarily by prominent women in Little Rock society.

While some leaders of the WEC, such as Adolphine Terry and Vivion Brewer, favored integration, the group’s advertised aim was to reopen the schools. The WEC emphasized through speeches and circulars that closed schools threatened stability and prosperity. The white business leadership belatedly entered the fray when segregationist school board members engineered the purging of forty-four teachers and staff. A recall election in May 1959 ousted the segregationists from the board and paved the way for high school classes to resume in the fall.

The legacy of the crisis was varied. The Little Rock African American community had discredited the official flouting of the law and segregationist extremism through the clear defiance of violence and intimidation. The WEC broke from the older forms of female activism tied to the prohibition of liquor and suffrage. The organization’s members continued to promote general political reform and interracial cooperation while edging toward more focused demands for expanded women’s rights. Faubus continued to thunder anti-integration rhetoric but avoided another showdown with national authorities. While denouncing the federal government, the governor also raised taxes and bolstered government services. This formula of catering to the right while advancing government modernization kept him in office for an unprecedented six terms.

Industry and Entertainment

Although the Little Rock school crisis discouraged new employers from locating in the city, manufacturing growth continued to surge in the state as a whole through the 1960s. The poultry firms secured better prices by processing ready-to-cook chickens to appeal to women who continued to cook and shop for their households. These companies also stimulated the expansion of long-distance trucking firms in northwest Arkansas. In 1960 Norge, an appliance manufacturer, announced that it would build a factory employing 2,000 in Fort Smith, revealing that not all of the arriving operations were in the lower-wage clothing and food-processing sectors. New jobs prompted population shifts. The larger Arkansas towns exceed the national urban growth rate throughout the 1950s. Arkansans who moved to the city not only became accustomed to gas heat and indoor plumbing, but they also found it easier to replicate a lifestyle viewed nightly on flickering television sets.

Just as Arkansans had once listened on the radio to native sons perform on the Lum and Abner and the Bob Burns programs, they watched Dick Powell, who was born in Mountain View (Stone County), in the early 1960s and, later in the decade, the variety shows of Glen Campbell and Johnny Cash, from Delight (Pike County) and Kingsland (Cleveland County), respectively. Campbell and Cash were among a number of musicians who honed their talents in the church and crop fields and forged notable careers by invigorating commercial music with the traditional strains from their youth. Johnnie Taylor and Al Green emerged from gospel groups to dominate the soul record charts in the late 1960s and 1970s. Conway Twitty and Charlie Rich jumped on the rockabilly band wagon in the 1950s but found greener pastures in Nashville country music circles.

While Arkansans watched the same television programs and listen to the same popular music as other Americans, their traditional preference for the outdoors gave a distinctive cast to modern recreation in the state. After World War II, the newly invigorated Arkansas Game and Fish Commission managed to replenish the white-tail deer population, which had nearly been erased by over-hunting. The agency authorized limited hunting seasons for the first time in the 1950s, and deer replaced squirrel as the game of choice for Arkansas hunters. Arkansans also began to abandon fishing from the banks of rivers as new lakes became the newest alteration of the landscape. In 1938, Congress approved a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers plan to construct a series of flood-control dams in the White River Basin. Over the subsequent decades, these construction projects led to the creation of Norfolk, Bull Shoals, and Greers Ferry lakes. These sites stimulated the emergence of the Arkansas tourism industry as well as the development of retirement communities.

If many Arkansans began to view nature as a backdrop for new forms of recreation, some in the northern uplands reacted to changes by demanding preservation of the natural environment. The intention of the Army Corps of Engineers to build a dam at Lone Rock on the Buffalo River led Neil Compton, a Benton County physician, to mobilize opposition to the project. By 1964, the environmentalists’ challenge compelled the corps to relocate the dam to preserve a larger section of the river. The compromise failed to quiet the controversy. The preservationists held firm while confronting opposition from Newton County citizens who believed the dam would jumpstart the economy of the chronically impoverished region. The corps cultivated these local allies. At the same time, tourist developers at the corps’s other lakes as well as AP&L, which worried about another federal hydroelectric project, supported the environmentalists. In 1965, Faubus ended the battle over the Buffalo River by requesting that the corps decommission the dam project.

Politics in a New Era for Arkansas

Faubus’s fear that the upland landscape of his youth was threatened by bulldozers and dams corresponded with his growing disdain for the other changes unfolding in the 1960s: civil rights, questioning of American Cold War policy, and the new youth culture. Other Arkansas politicians responded with ambivalence to the new conditions. Both of Arkansas’s U.S. senators, John L. McClellan and J. William Fulbright, continued to vote against federal civil rights measures on states’ rights grounds, yet McClellan routed a steady flow of federal dollars into river, levee, and drainage projects, while Fulbright became the most notable congressional opponent to President Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam War policy. Led by Representative Wilbur Mills, who chaired the Committee on Ways and Means, the House delegation complemented the influence of the senators. No state enjoyed greater clout in Congress by the 1960s.

Faubus’s conservatism did not render him inflexible. While denouncing civil rights measures, the governor cooperated with L. C. Bates in selecting Black appointees for state posts rather than risk the withholding of federal funds by continuing overt public employment discrimination. Mindful of the growing African American voting rolls, Faubus cooled his more incendiary rhetoric without sacrificing his segregationist support.

As new civil rights organizations launched broader integration campaigns, the trauma left over from the 1957 crisis moderated the white response. In 1961, several Black physicians in Little Rock formed the Council of Community Affairs, which pressed municipal officials to desegregate public parks and buildings. The following year, the Arkansas Council on Human Relations, an interracial group that fostered improved race relations through education and dialogue, requested that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Atlanta send an organizer to jumpstart a sit-in movement against the downtown Little Rock lunch counters. Beginning with the F. W. Woolworth’s store and then expanding to other Main Street department stores, students from Philander Smith College sat peacefully at the lunch counters until arrested. Business leaders feared embarrassing national publicity and persuaded the store managers to open the dining areas to all customers. By the end of 1963, Little Rock lifted segregation regulations on public auditoriums, parks, and playgrounds. The statewide voting rights campaign of the SNCC confronted greater hostility but succeeded, by 1968, in doubling the number of registered Black voters to sixty-eight percent of those who were eligible. A significant number of these new voters cast their first ballots for Winthrop Rockefeller, who ran for governor in 1964 and again in 1968.

Faubus’s long tenure as governor had given him unprecedented influence over government agencies and their clients. He also enjoyed political and monetary support from the varied business interest groups that grew as the state’s economy diversified. Political observers acknowledged that Witt Stephens, founder of the state’s leading bond firm and president of Arkansas Louisiana Gas, was the most influential power broker. His early alliance with Faubus strengthened Stephens and eroded the clout of AP&L. Despite his many advantages, Faubus spied storm clouds on the horizon. While he had expanded the scope of government, Faubus had operated in a climate of old-fashioned corruption that proved unpalatable to a rising number of urban citizens. In 1964, the ratification of the federal amendment against poll taxes and the court-ordered redrawing of legislative districts to reflect population shifts heralded a new era of politics.

Although he had appointed Rockefeller to chair the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission, Faubus backed a legislative attempt to oust the former New Yorker from the position in 1963. Rockefeller had been critical of the governor’s segregation policies and was vigorous in trying to resurrect a viable Republican Party. In 1964, the conservative wing of the national Republican Party showed its strength with the nomination for president of Senator Barry Goldwater, who had opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In Arkansas, Rockefeller envisioned a broad-based party that would forge a coalition of Black and moderate white citizens. Faubus was also running against the current of his own party as President Johnson touted his civil rights achievements in his bid for a new term. Rockefeller’s loss to Faubus in the November gubernatorial election surprised few. Buoyed by the highest vote percentage enjoyed by a Republican since Reconstruction, however, Rockefeller immediately announced he would try again in two years.

In March 1966, Faubus announced that he was retiring. The resulting wide-open Democratic primary election led to the nomination of James Johnson, who had not altered his segregationist views. Fearing that a Johnson victory would revive the unrest and embarrassment associated with the events of 1957, many moderate white Democrats voted for a Republican for the first time in their lives. More significantly, nearly all of the 75,000 black voters chose Rockefeller, bringing him to victory as governor.

Rockefeller’s victory did not create a real two-party political system in Arkansas, but candidates for office were freed from the obligation to declare themselves defenders of segregation and racial discrimination. A new generation of political leaders would emerge out of the shadows of the Old Guard of the Faubus period. The social and economic transformation of Arkansas in the decades following World War II set in motion the overdue reform of a political system long mired in factionalism and narrow local interest. Rising prosperity and greater democracy were the underpinnings of the bridge between Arkansas and the modern nation.

For additional information:

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission. Arkansas Wildlife: A History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Beals, Melba Pattillo. Warriors Don’t Cry: A Searing Account of the Battle to Integrate Little Rock’s Central High. Little Rock: Washington Square Press, 1994.

Compton, Neil. The Battle for the Buffalo River: A Twentieth Century Conservation Crisis in the Ozarks. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Holley, Donald. The Second Great Emancipation: The Mechanical Cotton Picker, Black Migration, and How They Shaped the Modern South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Huckaby, Elizabeth. Crisis at Central High: Little Rock 1957–1958. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Lester, James E. A Man for Arkansas: Sid McMath and the Southern Reform Tradition. Little Rock: Rose Publishing, 1976.

Lewis, Julianne and Thomas A. DeBlack, eds. Civil Obedience: An Oral History of School Desegregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1954–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

McMath, Sidney S. Promises Kept: A Memoir. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Murphy, Sara Alderman. Breaking the Silence: Little Rock’s Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, 1958–1963. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Times of an American Prodigal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Smith, C. Calvin. War and Wartime Changes: The Transformation of Arkansas, 1940–1945. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1986.

Strausberg, Stephen. From Hills to Hollers: Rise of the Poultry Industry in Arkansas. Fayetteville: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, 1995.

Urwin, Cathy Kunzinger. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–71. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Woods, Randall Bennett. Fulbright: A Biography. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Ben Johnson

Southern Arkansas University

Arkansas Democrat Newsroom

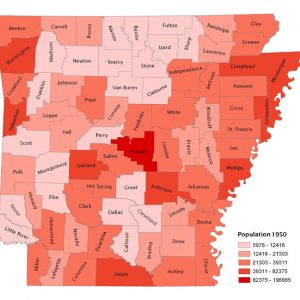

Arkansas Democrat Newsroom  Arkansas Population, 1950

Arkansas Population, 1950  Hazel Walker's Arkansas Travelers

Hazel Walker's Arkansas Travelers  "The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood  Central High School

Central High School  Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard

Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard  Christ of the Ozarks

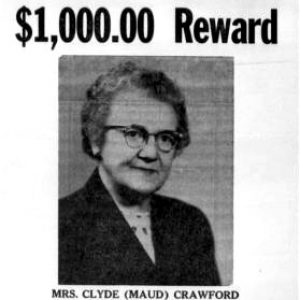

Christ of the Ozarks  Maud Robinson Crawford Reward Poster

Maud Robinson Crawford Reward Poster  Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High

Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High  "Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson

"Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson  Faubus Campaign Brochure

Faubus Campaign Brochure  "Forty Days," Performed by Ronnie Hawkins

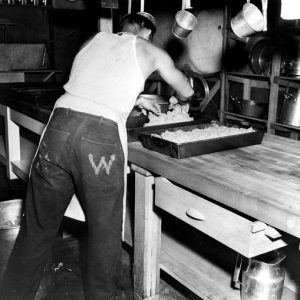

"Forty Days," Performed by Ronnie Hawkins  German POW at Camp Chaffee

German POW at Camp Chaffee  Glenwood Newspaper

Glenwood Newspaper  Greers Ferry Dam Dedication

Greers Ferry Dam Dedication  Hoxie Glee Club

Hoxie Glee Club  Jerome Relocation Center Children

Jerome Relocation Center Children  Sue Kidd Baseball Card

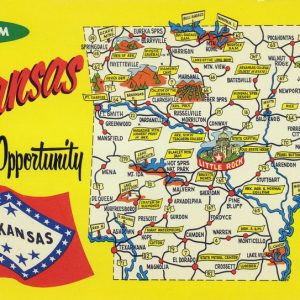

Sue Kidd Baseball Card  "Land of Opportunity" Postcard

"Land of Opportunity" Postcard  Little Rock Downtown

Little Rock Downtown  Lum and Abner Radio Show

Lum and Abner Radio Show  Sid McMath with Truman

Sid McMath with Truman  Ordnance Plant Workers

Ordnance Plant Workers  Original Tuskegee Airmen

Original Tuskegee Airmen  Pine Bluff Arsenal Assembly Line

Pine Bluff Arsenal Assembly Line  "Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess

"Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess  Rogers Broiler Show

Rogers Broiler Show  Cartoon drawn by John Sorensen

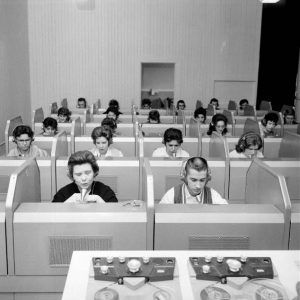

Cartoon drawn by John Sorensen  Southern State College Language Lab

Southern State College Language Lab  There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere

There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere  Titan II Missile Convoy

Titan II Missile Convoy  West of the Alamo Lobby Card starring Jimmy Wakely

West of the Alamo Lobby Card starring Jimmy Wakely  First Opening of Wal-Mart

First Opening of Wal-Mart  Walnut Ridge Army Flying School

Walnut Ridge Army Flying School  Welcome to Arkansas Sign

Welcome to Arkansas Sign  Williwaw War

Williwaw War

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.