calsfoundation@cals.org

Wiley Austin Branton Sr. (1923–1988)

Wiley Austin Branton was a civil rights leader in Arkansas who helped desegregate the University of Arkansas School of Law and later filed suit against the Little Rock School Board in a case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court as Cooper v. Aaron. His work to end legal segregation and inequality in Arkansas and the nation was well known in his time.

Wiley Branton was born on December 13, 1923, in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), the second child of Pauline Wiley and Leo Andrew Branton. His father and paternal grandfather owned and operated a taxicab business. His mother was a schoolteacher in the segregated public schools prior to her marriage. He had three brothers and a sister.

Branton was educated in the segregated schools of Pine Bluff and attended the local African-American college, Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), prior to being drafted into the U.S. Army in 1943 during World War II. His wartime experience opened his eyes to the horror and madness of prejudice. Returning from military service, Branton became active in civil rights activities while operating the family business. He married Lucille Elnora McKee in January 1948. They had six children.

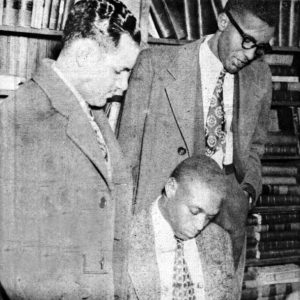

At this time, he also was involved in integrating the University of Arkansas School of Law. The university, similar to most other Southern colleges and universities, traditionally had refused to admit African Americans as full-time students. In 1948, U.S. Supreme Court opinions had required the state-supported graduate schools of several other states to admit black students. Branton was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Arkansas State Conference of Branches when Arkansas governor Ben Laney held a statewide conference to promote his idea for a regional graduate school for black students. Branton was so disgusted with the discussion that he declared his intention to register in the undergraduate school of the university. He also persuaded a friend, Silas H. Hunt, to register for the university’s School of Law. (Hunt had graduated from Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal and was planning to attend the University of Indiana School of Law.) When they traveled to Fayetteville (Washington County) to attempt registration, accompanied by Pine Bluff attorney Harold Flowers and photographer Geleve Grice, Branton was refused admission but Hunt was accepted.

Branton, in the 1948 election, worked to get African Americans in Pine Bluff to purchase poll tax receipts and persuaded many to vote. Given that he distributed sample ballots (which were obviously homemade), the local prosecuting attorney charged Branton with election fraud, and he was ultimately convicted and fined $200. He appealed his conviction, but the Supreme Court of Arkansas the following year, in the case of Branton v. State, upheld the ruling with only one dissent, asserting that Branton’s demonstrations of how to mark a ballot properly constituted voter intimidation.

Branton was admitted to the School of Law in January 1950, becoming one of the “Six Pioneers” at the school. He was the fifth black student admitted to the school and, in 1953, the third to graduate. Branton opened a law office in Pine Bluff after his admission to the bar and conducted a general practice between 1953 and 1962.

In early 1956, Branton filed suit against the Little Rock School Board for failing to integrate the public schools properly after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision. Branton’s suit precipitated the desegregation of Central High School and ultimately was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court as Cooper v. Aaron in 1958. During the years he was involved in this case, Branton worked primarily with the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.’s director-counsel, Thurgood Marshall, who presented the arguments to the Supreme Court. They won the case, and the school board was ordered to proceed with desegregation. Branton and Marshall became fast friends during this period of great stress and potential violence. The case made Branton nationally known and led to his recruitment as executive director of the Voter Education Project in 1962.

During a thirty-month period between 1962 and 1965, Branton worked with representatives of the major African-American civil rights organizations to register almost 700,000 new black voters in eleven Southern states. This was accomplished despite massive resistance from the white population of most of those states. During this time, Branton met and mentored a young Vernon E. Jordan Jr., who succeeded him as executive director of the Voter Education Project and eventually became Branton’s second close friend.

Following this successful venture, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey asked Branton to become executive director of the President’s Council on Equal Opportunity and help coordinate implementation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. When the council was abolished by President Lyndon B. Johnson in September 1965, the president asked Branton to move to the Department of Justice as his personal representative and continue working to implement the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1967, after two years with the Justice Department, Branton was named executive director of the United Planning Organization (UPO), which provided social services programs to Washington DC under grants through the Equal Opportunity Act of 1964. In this role, Branton helped Washington DC recover from the effects of riots that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. From the UPO, Branton moved to the Alliance for Labor Action in 1969, where he helped Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers Union, to create social service programs across the country. Reuther’s unexpected death in May 1970 lessened the program’s progress. Branton left the Alliance for Labor Action in August 1971 and returned to the private practice of law.

He joined with others to create the firm Dolphin, Branton, Stafford and Webber in Washington DC. There, he practiced law, at one point supervising the successful effort to obtain court-ordered protection of illegal FBI surveillance files on Dr. King. He also continued his active involvement in the many social organizations of which he was a member. The most prominent among these were the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc.; the NAACP; the National Bar Association; the Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity; and the Masons.

In December 1977 came the announcement that Wiley Branton would be the new dean of Howard University School of Law. He took that post during a troubled period in the school’s existence and was proud of his work in restoring some of its historical prominence as a creator of black civil rights lawyers. Branton would remain dean for five years, leaving in September 1983 to join the Chicago law firm of Sidley and Austin in its Washington DC office. There, in a reprise of earlier years, he resisted Senator Jesse Helms’s efforts to obtain access to the FBI’s files on Dr. King.

Branton died of a heart attack on December 15, 1988, two days after his sixty-fifth birthday.

For additional information:

Adelman, Kenneth L. “You Can Change Their Hearts.” The Washingtonian 107 (March 1988): 135.

Freyer, Tony. The Little Rock Crisis, A Constitutional Interpretation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1984.

Kilpatrick, Judith. There When We Needed Him: Wiley Austin Branton, Civil Rights Warrior. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. “Wiley Austin Branton and Cooper v. Aaron: America Fulfills its Promise.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Spring 2006): 7–23.

———. “Wiley Austin Branton and the Voting Rights Struggle.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 26 (2004): 641–701.

———. “Wiley Austin Branton: A Role Model for All Times.” Howard Law Review 48 (Spring 2005): 827–840.

Kirk, John A. “‘He Founded a Movement’: W. H. Flowers, the Committee on Negro Organizations and Black Activism in Arkansas, 1940–1957.” In The Making of Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement in America, edited by Brian Ward and Tony Badger. London: Macmillan, 1996.

Judith Kilpatrick

University of Arkansas School of Law

Wiley Branton

Wiley Branton  Wiley Branton

Wiley Branton  Branton Grave

Branton Grave  Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers

Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.