calsfoundation@cals.org

Election Fraud

Questionable balloting procedures and fraudulent vote counts began early in Arkansas’s political history and were a regular component of the state’s politics, especially in rural areas, until about 1970. The state’s tradition of one-party rule in which consequential elections were decided in party primaries, the absence of unbiased political information in the form of independent newspapers, and a traditionalistic political culture in which the activities of the ruling elite were generally unquestioned by the masses all contributed to an environment in which fraud—fundamentally problematic for a representative democracy—could persist.

Such fraudulent behavior in Arkansas had its roots in the politics of “The Family,” the Democratic regime that controlled the state’s politics in the period following statehood. This Johnson-Conway-Sevier-Rector cousinhood accumulated 190 years of public office-holding, including two U.S. senators and three governors in antebellum Arkansas. Other offices went only to their partisans, and the Family’s control of all aspects of the election machinery in the state made that control easier. For instance, U.S. senator Ambrose Sevier, about to be caught up in a public bank scandal in the early 1840s, was quickly reelected by the state legislature before an investigation of his impropriety came to light. The fraud of this era created a norm that would follow even after the Family’s political demise.

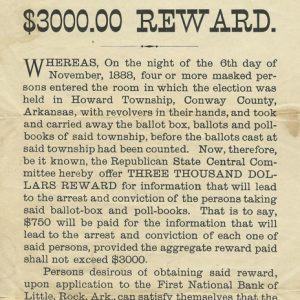

In the Reconstruction era, election fraud continued, most tellingly in the conflicted 1872 gubernatorial election between Elisha Baxter and Joseph Brooks that culminated in what came to be called the Brooks-Baxter War. Fraud intensified when the Redeemers, the Democrats who returned to political power in the state following the Reconstruction era, felt threatened electorally by a fusion of Republicans and Populists during the 1880s. The most consequential election in the state during this period was the governor’s election of 1888 in which an allied group of political factions supported Charles M. Norwood, the gubernatorial candidate of the dissident Union Labor Party, against Democrat James P. Eagle. By the standards of states accustomed to closely competitive general elections, the attempt was an abject failure. Eagle received 99,229 votes to the 84,273 votes cast for Norwood. For those unaccustomed to genuine competition, however, this election was ominously close, especially because of the amount of fraud that had been necessary to secure even this “narrow” victory. A congressional election in the central portion of the state between Democrat Clifton R. Breckinridge and John Clayton, running as a Republican, resulted in an even more marginal (and even more dubious) Democratic victory. When Clayton attempted to provoke a federal investigation into the voting process, he was murdered in Plumerville (Conway County).

These events were followed by “electoral reform” in the form of an 1891 state law. Especially considering the fraud, thuggery, and violence that had come to characterize the election process, the Election Reform Act of 1891 had some genuinely laudable provisions for those with a normative preference for clean elections. One element of the law, for example, prohibited the last-minute transfer of polling places. However, the two most important provisions of the statute were obviously intended to ensure the future electoral fortunes of the Democratic establishment. One effectively turned over all the state’s election machinery to the Democratic Party, with only token representation for minority parties. The other disfranchised illiterates (over one-fourth of the population at that time) by removing all political symbols from the ballot and providing that only the precinct judges (all Democrats) could assist illiterates in preparing their ballots.

During this period, the legislature also initiated a state constitutional amendment that placed a one-dollar poll tax on the “privilege” of voting, and in 1892 (by which time the 1891 reforms were in effect) this amendment was ratified. While scholars debate the extent to which these changes reflected a genuinely reformist impulse in reaction to the flagrant election abuses that had become commonplace, there can be no dispute over the resulting dramatic decline in voting—from 191,448 participants in the 1890 election to 129,337 in 1900—nor the growing importance of local political leaders with an ability to “deliver” the votes in their geographical enclaves.

According to V. O. Key, the foremost scholar on the politics of the South during this period, “These local potentates loom larger in Arkansas than in most southern states.” In the absence of party competition to clarify issue differences and of mass technology for reaching the voters, a statewide contest depended largely upon lining up the support of local leaders, often housed in county courthouses or city halls, who could corral their area’s vote. The foremost function of any statewide campaign manager was to line up these local bosses, and in many instances it was necessary to bargain on the basis of a quid pro quo. One gubernatorial campaign manager of the 1940s recalls, “Some wanted jobs, some wanted roads, some wanted both—but they all wanted something.” Many also expected a cash payment, euphemistically called “walking-around money.”

Virtually any statewide contest was tainted by the tactics necessary to ensure victory in certain counties, and despite numerous charges of fraud by the losers and occasional court challenges, the courts were generally as inclined as the citizenry to look the other way. Southern politics scholar Boyce Drummond, writing in 1957, concluded that “at least three gubernatorial races, two United States Senatorial races, and one Congressional race since 1930 were decided by corrupt practices.” Key concluded that while “Tennessee has the most consistent and widespread habit of fraud,” Arkansas was “a close second.”

Despite a law requiring such, there were almost no voting booths in Arkansas until the late 1960s; thus, real or perceived intimidation of voters by poll workers appointed to their posts by the local leaders generally achieved the desired goal. Other, more entrepreneurial, voters asked for something in return for their votes. In Newton County, for example, it was traditional to wait outside the courthouse on election day until one got the “highest dollar” and then a congratulatory slug of whiskey afterward. However, should such practices prove insufficient, there remained the infinite possibilities of outright fraud: deliberate defacement and subsequent discarding of ballots as they were counted and wholesale destruction (through burning, trashing, and even, in one instance, eating) of ballots if necessary. Absentee ballots were particularly susceptible to such fraudulent acts. Perhaps most troubling was the role of poll tax receipts, voters’ ticket to the voting process, in electoral shenanigans. Savvy politicians learned to monitor the poll tax for citizens who failed to meet the deadline for payment and pay the tax (and receive the receipt) for the prospective voters. Unless challenged, anyone could vote who showed the poll tax receipt and signed the election register. It was not uncommon for a single person to cast multiple votes as proxies using such receipts, thus giving a local potentate immense electoral power.

Based on local mores and the perceived stakes of the outcomes of statewide elections, these kinds of practices were much more widespread and flagrant in some localities than in others. Perhaps the leader in electoral corruption was Garland County, where the sustainability of illegal gambling operations absolutely necessitated a compliant state political establishment and where Leo McLaughlin controlled Garland County politics from his seat as mayor of Hot Springs. Sidney McMath and other leaders of the so-called GI Revolt returned home after World War II and challenged McLaughlin’s control. In the 1946 Democratic primary, McLaughlin used control of poll taxes to defeat the GI slate of candidates except McMath, who was elected prosecutor. In the fall general election, those who had been denied election in the primary all ran as independents. Included on the ticket was an independent candidate for Congress, important because it allowed a challenge of the poll tax issue in federal court. An investigation of the record showed that poll tax receipts had been issued in alphabetical order in every city ward. Handwriting experts provided evidence that the same hand had signed for all the receipts. Within months, McLaughlin was on his way to prison, and his machine was broken. The GI Revolt, seen in other counties along with Garland, sensitized Arkansans to the shame of widespread, casual election fraud and the desirability of honestly conducted elections.

McMath rode his role as the leader of the movement to the governorship in 1948. Despite his success at the state level, electoral fraud in the state did not end. Indeed, in his six victories in gubernatorial races starting in 1954, Governor Orval Faubus developed an immensely powerful statewide machine. Thus, as Winthrop Rockefeller began to build a state Republican Party to challenge the Faubus-controlled Democratic Party, he saw electoral reform in the state as an essential element. After his loss to Faubus in the 1964 governor’s race, Rockefeller funded the Election Research Council that worked with the League of Women Voters to develop the data that would justify major reform. The investigators found that a majority of absentee ballots cast in 1964 in the state were invalid, and they uncovered clear evidence of election-day fraud at polling places around the state.

When elected governor, Rockefeller fought for reforms such as private balloting. But, more than changed laws, factors such as a change in public expectations about the sanctity of the vote, a vibrant two-party system, and an independent press that could uncover problematic electoral practices ultimately undermined fraud in the state. While the mechanics of voting continue to be dogged by problems in each election cycle in parts of the state and disputes still arise about the interpretation of state election laws, these clearly are not the purposeful shenanigans seen as recently as the early 1970s. Governor Mike Huckabee’s statement on Don Imus’s nationally syndicated radio program just before the 2000 election—that Arkansas was a “banana republic” rife with “ballot fraud”—was seen even by his own partisans as undeniably hyperbolic.

For additional information:

Blair, Diane D., and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government: Do the People Rule? 2nd ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Drummond, Boyce A. “Arkansas Politics: A Study of a One-Party System.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 1957.

Glaze, Tom, with Ernie Dumas. Waiting for the Cemetery Vote: The Fight to Stop Election Fraud in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Key, V. O., Jr. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Random House, 1949.

Jay Barth

Hendrix College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.