calsfoundation@cals.org

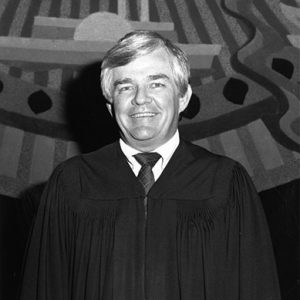

Thomas Arthur (Tom) Glaze (1938–2012)

Thomas Arthur (Tom) Glaze was a lawyer whose crusade against election fraud in the 1960s and 1970s propelled him into politics and a thirty-year career as a trial and appellate judge. Fresh out of law school in 1964, Glaze went to work for an organization that investigated election fraud and irregularities—an organization secretly funded by Republican Winthrop Rockefeller. The experience consumed him and inspired the rest of his legal career. As a deputy attorney general in 1969, Glaze rewrote Arkansas election laws, although the Arkansas General Assembly drastically weakened his draft before enacting the reforms. He was a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court for twenty-two years, retiring in 2008. He recounted his battles with what he called “vote thieves” in a memoir, Waiting for the Cemetery Vote, which was published shortly before his death.

Tom Glaze was born on January 14, 1938, in Joplin, Missouri, one of four sons of Harry Glaze and Mamie Rose Guetterman Glaze. His mother worked on an assembly line in an airplane-parts plant. His father, known as “Slick,” was a sheet-metal worker. Glaze played on every athletic team in high school and enrolled at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) to play football and baseball. He became angry at the football coaches, however, the first week of practice and quit the team. He was a catcher for the Razorback baseball team for four years.

He married Susan Askins of Joplin; they had two sons and two daughters.

While awaiting a call to military duty in the summer of 1964 (he was finally rejected for medical reasons), he took a job with the Election Research Council (ERC), an organization funded by Win Rockefeller, who ran for governor that year. The ERC was directed by John H. Haley, a lawyer with the Little Rock (Pulaski County) firm of Rose, Meek, House, Barron, Nash and Williamson, later called the Rose Law Firm. The organization was to investigate election irregularities and study election procedures with an eye toward reform. During the primaries and general election that year, he was dispatched to counties troubled by election-day skullduggery. What he saw angered him. When other lawyers with the ERC moved on after the election, Glaze continued to investigate elections while starting a law practice in Little Rock. He worked for Rockefeller for a few months in 1965 to develop an organization for future campaigns. Rockefeller was elected governor in the next two elections, 1966 and 1968.

When Benton (Saline County) lawyer Joe Purcell, a Democrat, was elected attorney general in 1966, he appointed Glaze deputy attorney general in charge of special projects and election laws. Glaze wrote numerous opinions to county officials and election commissioners interpreting the state’s patchwork of voting laws and instructing officials on how to comply with the laws. He rewrote the entire election code to secure secrecy of the ballot and to make it harder for sheriffs, county clerks, and election judges and clerks to manipulate voting results. Purcell submitted the new code to the legislature in 1969, but he had to agree to weaken the reform of absentee-ballot rules to get it passed. Glaze soon resigned and started a private law practice again, but he then formed a new election organization called The Election Laws Institute (TEL Institute) to monitor elections and educate election officials.

TEL Institute’s work threw Glaze into a series of lawsuits and out-of-court legal battles from 1970 through 1976, starting with his disclosure in 1970 that thousands of fraudulent names were attached to initiative petitions for a third party. He was furious at the lack of punishment for those responsible for the fraud.

Most of the battles Glaze faced were in counties that were nationally or regionally famous for suspected voting misconduct, mainly Conway and Searcy counties. A group of women in Conway County who called themselves “The Snoop Sisters” enlisted Glaze’s help in combating Sheriff Marlin Hawkins’s control of the election machinery. Glaze’s conflict with Hawkins and other officials in Conway and Faulkner counties—in the courthouses and in courtrooms—ended in 1976 with the defeat of Hawkins’s candidates, which spelled the end of his thirty-five years of control of the county and of the election machinery. A federal lawsuit at the same time in nearby Searcy County ended with a consent decree in which both Republicans and Democrats acknowledged the systematic buying of votes in every election and agreed to stop it.

The election wars made Glaze a familiar figure, with his caricature featured in political cartoons. In 1978, he ran for chancery judge in Pulaski County and was elected. He also married Phyllis Laser, a Little Rock businesswoman, the same year, his first marriage having ended in divorce in 1974.

In 1980, he ran for a seat on the new Arkansas Court of Appeals, which was created two years earlier to relieve the huge workload of the Arkansas Supreme Court. Six years later, he ran for justice of the Supreme Court to replace the retiring George Rose Smith. He was elected three times to eight-year terms on the court, finally retiring in September 2008 in the advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease.

Though he was conservative and committed to judicial restraint, he participated in the most sweeping decisions of the Arkansas Supreme Court, striking down laws that allowed discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and ordering an overhaul of the state system for financing public education. He started as the most reluctant of the judges in Arkansas’s major school funding case (Lake View School District No. 25 v. Huckabee), but he became its most ardent advocate, demanding that the governor and legislature meet the Arkansas Constitution’s requirements that the state supply every child with a suitable and equal education.

He never lost his passion for clean elections. Each time election disputes reached the Supreme Court and he was on the losing side, he wrote angry dissents chastising the court for following the historic pattern of failing to punish offenders or order a complete resolution of voting issues.

He died on March 30, 2012. He is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Glaze, Tom, with Ernie Dumas. Waiting for the Cemetery Vote: The Fight to Stop Election Fraud in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Sandlin, Jake. “Glaze, Former State Justice, Dies at 74.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 31, 2012, pp. 1A, 3A.

Tom Glaze Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Tom Glaze

Tom Glaze

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.