calsfoundation@cals.org

Six Pioneers

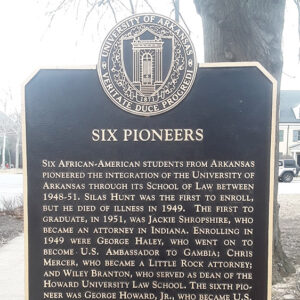

The Six Pioneers were the first six African American students to attend the University of Arkansas School of Law: Silas Hunt, Jackie Shropshire, George Haley, Christopher Mercer, Wiley Branton, and George Howard Jr. Making the school the first institution of higher education in the South to desegregate voluntarily, they attended from 1948 to 1951, and five of the six graduated.

Arkansas Industrial University (which would later become the University of Arkansas) opened in Fayetteville (Washington County) in January 1872, and at least one African American student arrived on campus to take classes at that time. While James McGahee likely received private tutoring rather than participating as a regular student, his presence on campus made the institution one of the earliest in the South to offer educational opportunities regardless of race. At the conclusion of the academic year, McGahee did not continue his studies, and no other African American student attended any part of the university for the next seven decades. The establishment in 1873 of Arkansas AM&N in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, allowed African Americans an opportunity to attend a public institution of higher education in the state, albeit a segregated one.

Prentice Hilburn, represented by attorney Scipio Jones, approached the university administration in 1941 for support to attend the law school at Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington DC. He was successful in his request and received funds from the university. In an effort to avoid admitting African Americans to graduate and professional programs at the University of Arkansas, the administration met with Black leaders and members of the state government in Little Rock to establish a new system. Working to prevent any future occurrences of funds being taken from the university to pay for the education of African Americans in subjects not offered by Arkansas AM&N, the meeting reached a solution. Up to $5,000 were to be used to fund requests for students wishing to attend programs in other, typically northern, states. The funds came from the appropriation of AM&N.

Clifford Davis applied for admission as a transfer student from Howard University Law School in 1946. His first-year tuition had been paid by the State of Arkansas, but he desired to return home due to the high cost of living in Washington DC. Davis was not admitted for the fall 1946 semester but reapplied the following year. Law school dean Robert Leflar realized that admitting African American students to the school would likely have to occur, as other options, such as creating regional graduate schools for African Americans, were considered too expensive. He began to work on creating spaces in the law school that would allow Davis and other Black students to attend classes while remaining segregated from white students. In January 1948, the university announced that African American students would be allowed to attend graduate and professional programs. Davis chose not to attend, however, as he was then in his last year of law school at Howard and did not wish to attend the University of Arkansas if only token steps of integration were taken.

As the first Black student actually to attend the University of Arkansas School of Law, Silas Hunt enrolled on February 2, 1948, making him the first African American to integrate a primarily white institution of higher education in the South. However, Hunt was forced to receive individual instruction from professors rather than attend class with other students, did not have equal access to the library or restroom facilities, and was forced to find accommodations in the Fayetteville community rather than on campus. Several white students eventually began to voluntarily attend Hunt’s classes. Hunt did not complete his degree and died from tuberculosis in 1949.

Jackie Shropshire began attending classes in the fall of 1948. A graduate of Dunbar High School in Little Rock, Shropshire served in the military and graduated from Wilberforce University in Ohio. Shropshire attended some classes alone with a professor, but overcrowding led to his attendance at other classes with white students. On the first day of class, a low wooden barrier separated Shropshire from the other students, but this wall was quickly removed. He lived with the Joiner family in Fayetteville.

George Haley and Christopher Mercer began classes at the law school in the fall of 1949. A graduate of Morehouse College in Georgia, Haley was a veteran of World War II. His father taught at AM&N and suggested the law school in Fayetteville rather than more expensive northern institutions. Mercer graduated from AM&N and worked as a principal at the Conway Training School in Menifee (Conway County). By this semester, no rail separated the three men from their classmates, but they were forced to sit in assigned seats and had to use a separate study room.

Wiley Branton of Pine Bluff enrolled at the law school in February 1950. After attending AM&N and serving in the military, he ran a family-owned taxi service in Pine Bluff before he declared his intention to register for the law school. He had persuaded his friend Silas Hunt to register and had attempted to do so himself at the same time but was refused, while Hunt was accepted. Branton was himself finally admitted two years after Hunt.

The final member of what became known as the Six Pioneers, George Howard Jr., arrived on campus for the fall 1950 semester. A Pine Bluff native, he attended Lincoln University in Missouri for two years after ending his service in the U.S. Navy. After spending his first semester living with a Black family in Fayetteville, Howard integrated on-campus housing in the spring of 1951. Haley and Mercer moved into the graduate dormitory the following semester. In his last year of law school, Howard was elected as representative for his dormitory in the student government.

Branton was married with three children and commuted between Pine Bluff and Fayetteville his first semester. Branton wanted his family to join him in Fayetteville, but he could not move them into the all-white married housing, and few options were available in Fayetteville’s small African American community. He purchased an empty lot and a World War II–era barracks building, moving the structure and modifying it to serve as a home.

Shropshire was the first of the Six Pioneers to graduate, receiving his degree on June 9, 1951. He practiced law in Little Rock (Pulaski County) until moving to Gary, Indiana, in 1956. He practiced law in that city for the remainder of his life, dying in 1992. Haley graduated the following year and practiced law in Kansas City, Kansas, for several years and served as a Kansas state senator. He moved to Washington DC in 1969, where he held various roles with the Federal Transit Administration and the U.S. Information Agency, also serving as envoy to Gambia. He received an honorary doctorate from the University of Arkansas in 2003.

Branton passed the bar in 1952 and graduated from law school the following year. He opened a practice in Pine Bluff and argued the case Cooper v. Aaron before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1958. Between 1962 and 1965, Branton led the Voter Education Project, which registered almost 700,000 African Americans across the South. He also served as executive director of the President’s Council on Equal Opportunity and in the Department of Justice overseeing implementation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Branton moved between public service and private practice with a stint as dean of the Howard University Law School. He died in 1988.

Mercer passed the bar in 1954 and graduated the next year. Working with Branton for a year, Mercer moved to Little Rock, where he served as a field representative of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and advised Daisy Bates—mentor to the Little Rock Nine—during the Central High Desegregation Crisis. He served as a deputy prosecuting attorney and in private practice before his death in 2012. Howard passed the bar in 1953 and completed both his BA and law degree in 1954. Practicing law in Pine Bluff, he filed lawsuits that desegregated the Dollarway School District and challenged the token integration efforts in Fort Smith. He was appointed to the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1977 and the Arkansas Court of Appeals in 1979, and President Jimmy Carter nominated him as a federal district court judge in 1980 for both the Eastern and Western Districts. From 1990 until his death in 2007, he served exclusively in the Eastern District and presided over Whitewater-related cases.

For additional information:

Kilpatrick, Judith. “Desegregating the University of Arkansas School of Law: L. Clifford Davis and the Six Pioneers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Summer 2009): 123–156.

———. “(Extra)Ordinary Men: African American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas before 1950.” Arkansas Law Review 53 no. 2 (2000): 299–399.

Leflar, Robert A. The First 100 Years: Centennial History of University of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas, 1972.

Nichols, Guerdon. “Breaking the Color Barrier at the University of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Spring 1968): 3–21.

“Plan to Admit Some Negroes to University.” Arkansas Gazette, January 31, 1948, p. 1.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Wiley Branton

Wiley Branton  George Howard Jr.

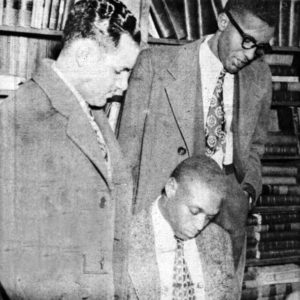

George Howard Jr.  Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers

Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers  Silas Hunt

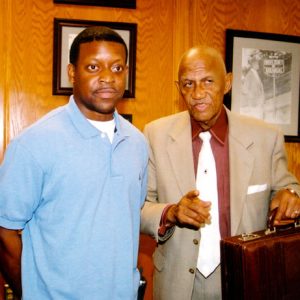

Silas Hunt  C. C. Mercer and Johnathan Carter

C. C. Mercer and Johnathan Carter  Six Pioneers Sign

Six Pioneers Sign

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.