calsfoundation@cals.org

Silas Herbert Hunt (1922–1949)

Silas Herbert Hunt was a veteran of World War II and a pioneer in the integration of higher education in Arkansas and the South. In 1948, he was admitted to the University of Arkansas School of Law, thus becoming the first African American student admitted to the university since Reconstruction and, more importantly, the first black student to be admitted for graduate or professional studies at any all-white university in the former Confederacy.

Silas Hunt was born on March 1, 1922, in Ashdown (Little River County) to Jessie Gulley Moton and R. D. Hunt. In 1936, his family moved to Texarkana (Miller County), where he attended Booker T. Washington High School; there, he received distinction as a member of the debate team and president of the student council before graduating in 1941 as class salutatorian. Upon graduation, he attended the Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (AM&N) at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), one of Arkansas’s historically black colleges (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff). Despite having to work at a number of jobs during his first year of college, including a construction job at the Pine Bluff Arsenal, he excelled academically and earned scholarships to pay for the remainder of his undergraduate education.

Hunt put his education on hold when he was drafted into the U.S. Army following America’s entry into World War II. He was stationed in Europe, where he served with construction engineers for twenty-three months before being seriously wounded at the Battle of the Bulge. After his recovery, Hunt returned to AM&N and graduated in 1947 with a BA in English. He worked briefly in the dean’s office after graduation while applying to numerous law schools.

Hunt was accepted by the University of Indiana School of Law and planned to enter the school when he learned of former AM&N classmate Ada Sipuel’s legal battle to overturn the University of Oklahoma College of Law’s policies against admitting black students. Many black students were embroiled in similar battles throughout the South, and like them, Sipuel was unsuccessful. But her courage and determination inspired Hunt and classmate Wiley Branton to take action. Southern colleges and universities were so rigidly segregated at the time that Southern states would actually pay the tuition for black students to attend one of the many black colleges rather than admit them to white universities. With the support of Branton and Lawrence Davis, president of AM&N, Hunt applied to the University of Arkansas School of Law with the hopes of breaking the color barrier and obtaining a law degree.

Having witnessed the negative publicity that segregation had brought to other white Southern universities, officials at university made a groundbreaking decision. On January 30, 1948, university officials announced that they would allow qualified black graduate students to be admitted to the university, which made Arkansas the first white Southern university since Reconstruction to admit black students. Black undergraduates, however, were still refused admission despite the fact that at least one such student had attended the university during Reconstruction. This was in accord with the 1938 U.S. Supreme Court decision Missouri ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada, which, while upholding the doctrine of “separate but equal,” required that states either provide legal education for African Americans at separate facilities or desegregate its law schools; desegregation of other institutions was not required. Arkansas officials reasoned that black state colleges provided an adequate education in other fields and that there were more than enough to serve the black population.

On February 2, 1948, Hunt—accompanied by Branton, Pine Bluff attorney Harold Flowers, and AM&N newspaper photographer Geleve Grice—arrived on the University of Arkansas (UA) campus in Fayetteville (Washington County) to meet with Dr. Robert A. Leflar, dean of the law school, and apply for admission to the law school. After a brief review of his academic record, Leflar was impressed enough to admit Hunt to the law school. This signified the first time a black student had been officially admitted to a white Southern university since Reconstruction and the first ever admitted for graduate or professional studies; Hunt became known as the first of the “Six Pioneers,” the name later given to those black students who desegregated the law school.

That spring, Hunt attended segregated classes in the basement of the law school. White students were not restricted from taking these classes, and in fact, between three and five students attended each of these classes regularly. Hunt was a serious student whose confident, humble nature allowed him to handle the pressure and publicity associated with his trail-blazing achievements and contributed to his friendship with some fellow students who studied with him.

He seemed destined for success, but illness cut short his studies. He was hospitalized at the Veteran’s Hospital in Springfield, Missouri, where he ultimately died on April 22, 1949, from tuberculosis, a possible complication from his war injuries. He is buried in the Stateline Cemetery in Texarkana.

To commemorate his achievements, UA began awarding the Silas Hunt Distinguished Scholar Awards in 2003 to deserving black students. In 2007, the state legislature made February 2, the day Hunt enrolled in classes, a memorial day in his name. In 2008, the University of Arkansas School of Law awarded Hunt a posthumous degree. In 2012, a sculpture by University of Central Arkansas professor Bryan Massey Sr. honoring Hunt was dedicated at the UA campus.

For additional information:

“Arkansas AM&N Grad—Combat Vet—Accepted.” Arkansas Traveler, February 3, 1948, p. 1.

Barton, Benjamin H. “A Tale of Two Law Schools.” Arkansas Law Review 78.2 (2025): 163–197. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/alr/vol78/iss2/4/ (accessed June 30, 2025).

Branam, Chris. “UA’s Mystery Man.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 4, 2005, pp. 1A, 13A.

Goodwin, Bennie. “Silas Hunt: The Growth of a Hero.” Mary Celestia Parler Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Gottsponer, Cathy C. “Campus Honors First Black Student.” University Reflections (Spring 1993): 3.

Kilpatrick, Judith. “Desegregating the University of Arkansas School of Law: L. Clifford Davis and the Six Pioneers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 68 (Summer 2009): 123–156.

Nichols, Guerdon D. “Breaking the Color Barrier at the University of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Spring 1968): 3–21.

“The Silas Hunt Legacy.” Program from the Celebration of the Integration of Higher Education in the South. University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, February 5–6, 1993.

“Students Voice Opinions on Admittance of Negro Students.” Arkansas Traveler, February 3, 1948, p. 1

Williams, Tammy. “UA Integrated for 50 Years.” Arkansas Traveler, February 11, 1998, pp. 1–3.

Richard A. Buckelew

Bethune-Cookman College

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

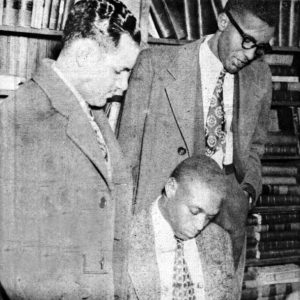

Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers

Silas Hunt; Wiley Branton; and Harold Flowers  Silas Hunt

Silas Hunt

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.