calsfoundation@cals.org

Camp Monticello

Camp Monticello was a World War II prisoner-of-war (POW) camp south of Monticello (Drew County). The camp was built in the southeastern part of the state because that area offered the required rural, isolated location. Advocacy by local civic leaders like Congressman William F. Norrell and the need for labor in the agricultural and timber industries also influenced the site choice. The camp, which housed Italian POWs, was one of four main camps and thirty branch camps in Arkansas that interned Axis prisoners.

The 1929 Geneva Convention regulated many of the conditions within POW camps. POWs were to be treated the same as the troops of the retaining power. Therefore, Camp Monticello was built to the standards of American military camps. A 1942 plan map indicates specifications for a standard 3,000-man internment camp with three compounds, medical facilities, and a garrison echelon arranged in a grid layout bounded by barbed-wire fences and guard towers. After some negotiations, additional hospital facilities and two compounds for officers and generals were added.

After the British captured much of the Italian high command at Tobruk and elsewhere in North Africa, Italian POWs, the vast majority of them officers, began to arrive in Monticello in 1943. Approximately four percent of the 50,000 Italian prisoners brought to the United States were non-commissioned officers, and seven percent were officers. Of the 1,850 men on Camp Monticello’s roster in 1944, there were 919 officers, including fifteen generals; 552 non-commissioned officers; and 389 enlisted men. Since there were so few enlisted men among the Italian POWs, military authorities agreed that it was not necessary to construct separate camps for officers and enlisted men as was done with the German POWs.

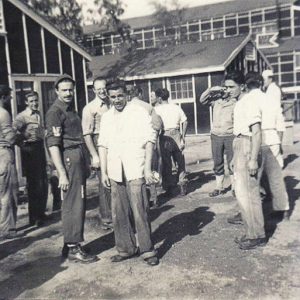

Archeology and historical research show that the POWs at Camp Monticello spent their time working, playing sports, attending Mass, preparing Italian meals, learning, and creating art. Under the terms of the Geneva Convention, prisoners received a monthly allowance depending upon their rank. Privates were required to work. Prisoners with the rank of corporal or sergeant could be required to work as supervisors. Officers were exempt from work assignments. Some POWs opted to escape the boredom of camp routine by working outside the camp on farms or with timber companies such as the Ozark Badger Lumber Company. Within the camp, a number of POWs worked in the hospital. Others worked on grounds and roads, on motor maintenance, or in the mess halls and PXs.

At the outset, the POWs were served food unlike anything they knew: hot dogs, corn, and Jell-O. A 1944 report indicates that 435 POWs worked in the mess halls; menus show that Italian meals were being prepared and served by that time.

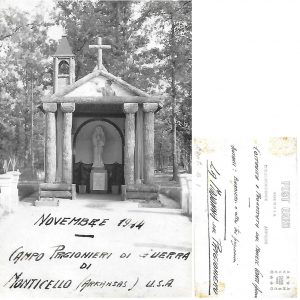

A majority of the POWs were Roman Catholic. Each compound had a chapel, and Mass was said almost every day. In one compound, the POWs constructed a chapel from packing boxes, asbestos tiles, and scrap lumber. They painted a prisoner of war behind barbed wire across the top, crafted a statue of the Madonna, and etched the words “Madonna Del Prignioniero Prega Per Noi” (Mother of the Prisoners Pray for Us) into the concrete base.

The Geneva Convention states that intellectual diversions and sports organizations should be encouraged for POWs. In addition to playing the game Americans call soccer, the POWs competed in tennis and boccie matches regularly. A film was shown once a week at the theater in the Garrison Echelon. Theater was also popular; the POWs wrote their own plays. They also formed an orchestra, which performed in a converted barracks used as a concert hall. The camp had a library with books in Italian and English. Most of the officers were well educated, but they were not necessarily English-speaking. The average soldier was neither. Many of the POWs could neither read nor write when they arrived. The officers gave lessons on various subjects, including mathematics, economics, English, and Italian.

The POWs also made artwork and other objects out of wood, stone, cement, and metal. In 1943, they held an exhibition of paintings and sculptures created by the prisoners. People from the surrounding area were invited. A representative with the International Red Cross described the landscapes and portraits as particularly good, but he was most impressed with the miniature models of such things as warships, the officers’ barracks, and the Sanctuary of the Madonna di San Luca near Bologna. Reports indicate that the prisoners also decorated some of the chinaware in the mess halls and, in addition to the chapel, created an enclosure for birds in captivity.

World War II drew to an end in 1945, and the closing of the camp was announced on October 4, 1945. The POWs were moved to other camps, some to the nearby German POW camp in Dermott (Chicot County), before being returned to Italy.

The War Department turned the camp over to the Surplus Property Board for disposal. Arkansas A&M College, now the University of Arkansas at Monticello, acquired the property. In anticipation of the largest enrollment at the school in years, the barracks were used for housing for married veterans and their families. A regular bus service transported veterans from the housing facility, known as Hartville, to campus. In 1947, Arkansas A&M designated much of the former camp for teaching livestock and forest management. In the twenty-first century, the land continues to be used as an experimental forest by the School of Forestry and Natural Resources, and some of the buildings from the motor park are used by the Drew County Fair Grounds. In 2018, the camp site was added to Preserve Arkansas’s list of most endangered places.

For additional information:

Barnes, Jodi A. “From Caffé Latte to Catholic Mass: The Archeology of a World War II Italian Prisoner of War Camp.” In Research, Preservation, Communication: Honoring Thomas J. Green on His Retirement from the Arkansas Archeological Survey, edited by Mary Beth Trubitt. Research Series No. 67. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 2016.

———. “‘Madonna Del Prignioniero Prega Per Noi’: An Intimate Archaeology of a World War II Italian Prisoner of War Camp.” In Intimate Archaeologies of World War II, edited by Jodi A. Barnes. Special issue, Historical Archaeology 52, no. 3.

———. “Nails, Tacks, and Hinges: The Archeology of Construction of Camp Monticello, a World War II Prisoner of War Camp.” Southeastern Archaeology (2018): 169–189. Online at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0734578X.2017.1420840 (accessed February 27, 2021).

Bragg, Don. “Growing Pains: Hank Chamberlin and the Arkansas A&M Forestry Program, 1946–1957.” Drew County Historical Journal 32 (2017): 11–38.

Keefer, Louis E. Italian Prisoners of War in America, 1942–1946: Captives or Allies? New York: Praeger Publishers, 1992.

Pomeroy, Michael. “Prisoner of War Camp Locates near Town…Keeps Italian Men Captured during War.” Drew County Historical Journal 3 (1988): 24–34.

Shea, William L. “From WAACs to Weevils: A Sketch of Camp Monticello.” Drew County Historical Journal 3 (1988): 17–23.

Smith, C. Calvin. “The Response of Arkansans to Prisoners of War and Japanese Americans in Arkansas 1942–1945.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Autumn 1994): 340–366.

Schnyder, Paul. Records of the Provost General, Field Reports. International Red Cross, Swiss Legation, November 8, 1943, RG 389. National Archives, Washington DC.

Jodi A. Barnes

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.