calsfoundation@cals.org

Environment

Arkansas’s physical environment features a mild climate, adequate rainfall, a rural and relatively uncrowded landscape, and diverse geology, which promote a variety of plants, animal life, and water resources. Understanding this environment requires examining the historical changes that have taken place, primarily those changes effected by human occupation. Each new culture and industry moving into the state has brought environmental changes, often dramatically affecting the landscapes of Arkansas’s six distinct geographic regions.

An Environmental Snapshot

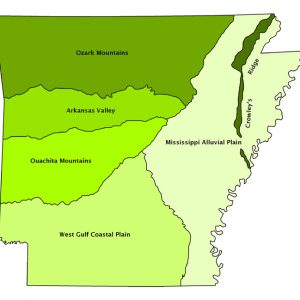

Arkansas contains 53,179 square miles (some thirty-four million acres) composed of six regions: the Arkansas River Valley, Crowley’s Ridge, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (also called the Delta), the Ouachita Mountains, the Ozark Plateau, and the West Gulf Coastal Plain. By 2022, more than 14.5 million acres was farmland, and more than 18.8 million acres was forest, including much of the 17.3 percent of the state that is public land. Arkansas has historically been largely rural, although it is becoming less so: in 2003, 83.4 percent of its 2,725,714 people lived outside metropolitan areas, while in 2022, 41 percent of its over three million people lived in rural areas. Arkansas ranked forty-fifth in the nation in 2022 in personal income ($52,618) and median household income ($53,980). Agriculture remains a significant economic force; the state was ranked first in rice production, seventh in chicken production, tenth in soybeans, and eighth in eggs in 2022. The state also ranks second in the nation in aquaculture, with species of baitfish and catfish raised in Arkansas. Although the state’s abundant natural resources include diamonds, petroleum, coal, natural gas, bauxite, bromine, wood, and limestone, there has been a relatively small amount of industrial development. This modest industrial growth is positively reflected in moderate air and water pollution statistics as compared with some surrounding states.

Arkansas has many natural and manmade lakes and 1,159 miles of navigable streams and rivers, which provide its citizens with recreation, hydroelectric power, and irrigation for agriculture. These waters also attract tourists. The state’s highest elevation is at Mount Magazine in Logan County at 2,753 feet above sea level; the lowest is along the Ouachita River in Ashley and Union counties at 55 feet above sea level.

Since long before statehood, Arkansas’s widely diverse geography has been the controlling force in its natural and cultural environment. The historical uses of those diverse habitats have in themselves modified the environment, making it necessary for people to adapt to the changed environment. For example, the rich black soil of the Delta first attracted single-crop planting of cotton. Single-crop planting so damaged the environment through overproduction that eventually farmers had to consider other crops, especially soybeans and rice. In northwestern Arkansas, the mountainous terrain, marginal at best for most agricultural development but situated near important economic markets—such as Kansas City and St. Louis, Missouri, and Tulsa, Oklahoma—suited the business of poultry. In return, the dramatic success of the poultry industry is counterbalanced by its enormous potential for pollution from waste in the form of litter and carcasses; the gradient of the hills and the speed with which polluted runoff—carrying potassium, nitrogen, phosphorous, and even arsenic—reaches streams and rivers facilitates this problem.

Arkansas sits just west of the Mississippi River and well south of the Mason-Dixon Line; this accounts for its identification with both South and West and, paradoxically, its lack of strong identification with either. Arkansas’s geography consists of six natural divisions distinguished by certain patterns of topography and vegetation. Major rivers include the Mississippi, which defines the eastern border; the Arkansas, which divides the state almost in half; the Ouachita and the Red in the southwest; and the White and the Buffalo National River in the north.

Before Statehood

Each region’s unique environment displays characteristics peculiar to its development or exploitation by human habitation. Native Americans, then Spanish and French explorers, then soldiers, then hunters, then naturalists and adventurers, then surveyors, then settlers and farmers, and finally townspeople and industry have had varying experiences with Arkansas’s environment and natural resources, depending on their point of entry. But what all the regions had in common in the early years of the frontier and then the state was their inhospitable access for exploration and later for pioneer settlement. The ruggedness of the Ozark Mountains and the vast, formidable swamps of the Mississippi Delta established barriers to the north and east. In addition, two natural pathways to the west and south—the Missouri River north of Arkansas led into Kansas and the West, while Mississippi’s Natchez Trace diverted travelers south of the state into Louisiana and Texas. As a result, only about 400 white people lived in Arkansas at the beginning of the 1800s.

The diversity of Arkansas’s geographic regions affected the lifestyles of its prehistoric cultures, the Paleoindians. For example, mound builders established villages in the river valleys to the south and east. The cultures that existed in Arkansas prior to the written record had left Arkansas or been absorbed by incoming cultures by the time the Quapaw arrived in the region in the 1500s and made their home in the southeastern Delta.

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain covers most of eastern Arkansas. Composed of silt several feet deep left by retreating waters of the Gulf of Mexico as much as 230 million years ago, this flat land was at that time largely bottomland hardwood forest and vast swampland. By the late 1500s, the Quapaw had established themselves in southeastern Arkansas. Water provided transportation by canoe or later flatboat in a land that could support few roads. They hunted, fished, and practiced subsistence farming, making little impact on the land. This was wild territory, with cane thickets, swamps, and bayous making travel difficult. The people adjusted their lifestyles to the dramatic fluctuations in the rivers and to the impenetrable virgin forests rather than adjusting the environment to fit them.

Soon, this dynamic changed. The relatively limited impact the Indians had made on the environment yielded to two points of stress on people and habitat: firearms and disease brought by European explorers. Gradually, the competition for food among the tribes and their own reduced numbers pushed the Quapaw northward up the rivers and onto the Grand Prairie, a region distinguishable from the Delta at that time. There they would displace smaller tribes and begin limited grazing and cultivation.

Even as the Quapaw were being forced north and west, more settlers were moving into Arkansas from the east, frequently over Crowley’s Ridge in the northeast. Once surrounded by water, Crowley’s Ridge remains an “island” of significantly different landscape from the Delta below, retaining some of the ancient ocean-bottom material as great rivers scoured the Delta. This high ground provided respite from the swamps and another form of adversity for explorers and settlers heading west from Tennessee through the Delta swamplands.

At about the same period as the Quapaw arrival, the West Gulf Coastal Plain was occupied by the Caddo, who were pushing into the Southwest from Texas. The region’s gentle hills, slow-moving streams, forests dominated by coniferous trees, and the red soil of the plain of the Red River provided abundant opportunity for farming, resources for pottery making, and an economic commodity—salt.

Also in the 1500s, a third tribe, the Osage, was arriving from the north to discover an entirely different landscape, the rugged Ozark Plateau. The Ozark Mountains suited the Osage, who were nomadic hunters and fishermen. Broadleaf deciduous forests supported ample game, such as deer and buffalo, until the coming of the white man and the Cherokee.

Another mountain range, the Ouachita Mountains south of the Ozarks in west-central Arkansas, served as a barrier between the southwest and the rich Arkansas valley, which attracted a second wave of settlers in the late 1800s. This group, the Cherokee, cleared forests and began developing settlements and cultivating fields, actions that ironically would prove their undoing. White settlers came to want these lands. Removal of the Cherokee was the result.

Not all physical changes were manmade. From late 1811 to 1812, an estimated 1,874 earthquakes began on the St. Francis River sixty-five miles southwest of New Madrid, Missouri, eventually destroying New Madrid. But even an earthquake could not deter the advance of population after the Louisiana Purchase. President Thomas Jefferson dispatched several expeditions to the new territory to map the area and collect physical specimens. One of these expeditions, the Hunter-Dunbar Expedition, ascended the Ouachita River to modern day Hot Springs (Garland County). On October 17, 1815, working under the appointment of President James Madison, Prospect K. Robbins and Joseph C. Brown began the Louisiana Purchase survey of two million acres of Arkansas wilderness. The starting point of the survey is now preserved as Louisiana Purchase State Park. Land grants in the Louisiana Purchase area dramatically increased the number of settlers. By 1835—just before statehood—Arkansas’s population had soared above 50,000, bolstered by the reports from Hunter-Dunbar and military land grants awarded for service in the War of 1812.

Population Growth Brings Change

Increased population brought important physical changes. The assaults on forests and water had begun, and, by 1820, the cultivation of cotton was firmly established in the lowlands. By the 1850s, cotton was king.

In 1827, a wagon road was completed between Memphis, Tennessee, and Little Rock (Pulaski County), the first of many ambitious engineering projects in Arkansas undertaken by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. A second road followed, to Fort Smith (Sebastian County), then another to the southwestern town of Fulton (Hempstead County) on the Red River. Called military roads, they initiated commercial and political passage among the regions, preparing the territory for statehood. The land, formerly accessible to so few, was opened to settlement.

More people meant new demands for control of the flooding in eastern Arkansas and more access overland into the mountains. The 1850s brought a new surge of people into and through Arkansas as part of the Gold Rush, also bringing many more miles of dirt roads. The Swamp Land Act, passed by Congress in 1850, approved the sale of 8.6 million acres of federally owned land (one-quarter of the state) to a state Board of Swampland Commissioners. By the 1860s, an Office of Commissioner of Public Works had been created to oversee construction of levees across the Delta and to promote the construction of railroads. In 1873, the state had 300 miles of railroad track.

In the era before the Civil War, cotton dominated the economic picture in east Arkansas, appropriating wetlands and forest with each developed acre. Lumbering, burning, plowing, and flood control through channeling and draining were the instruments of change, which would result, especially in the Delta, in a new landscape. An economy based on the trees of the dense forests in northeastern Arkansas created a woodpile for steamboats in Osceola (Mississippi County) and a logging camp in West Memphis (Crittenden County), but it essentially self-destructed. The trees—and much of the habitat for the prairie chicken, the red-shouldered hawk, the Eastern elk, the bison, the passenger pigeon, the swan, and the ruffed grouse—were gone.

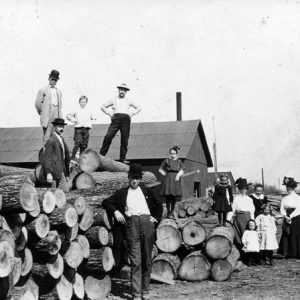

Coal was discovered in Johnson County in the 1830s, and the first state geological survey was made in 1858 to identify the state’s mineral resources. But none of these resources would be more significant than the forests. The environment of the Ozarks and the Ouachitas was about to change. Railroad construction propelled a fledgling lumber industry and encouraged a population shift away from the river corridors. Sawmills sprang up across the state. By 1900, the crew of a large sawmill could produce 100,000 board feet in a day. Because of the railroad main lines and connecting trunk lines, mills could be placed anywhere and picked up and moved on after a tract was cut. As the early homesteaders practicing one-crop farming had done, when one place “played out,” foresters moved to a new one. Dramatic descriptions by early naturalist settlers of enormous flotilla of cedar logs floating down the Buffalo River are witness to the magnitude of the cuts. Between 1880 and 1920, what one of the first explorers of the state, Thomas Nuttall, had described as “one vast trackless wilderness of trees” had been cleared. Almost no virgin timber remained. A history of that period, For the Trees, states that, “by the end of the 19th century, choice timber species, such as cherry and walnut, had become hard to find. Virgin white oak and pine were found only in the more inaccessible locations. Also becoming hard to find were the bear, the panther, and even deer.”

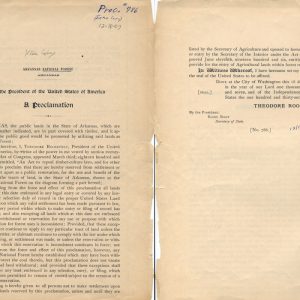

In 1907, during this period of extensive forest cutting, President Theodore Roosevelt established the Arkansas National Forest (renamed the Ouachita National Forest in 1926), recognizing that the forests belonged to the nation and needed to be protected. The Ozark National Forest was added in 1908, with the addition in 1960 of the St. Francis National Forest in the eastern part of the state. Many of the efforts of early forest rangers centered not on the issue of preventing the cutting of trees but on fire suppression because of the common practice among pioneers of using fire to clear and cultivate land. Although Roosevelt’s action appears farsighted to present-day environmentalists, other voices had already begun to be raised in the name of conservation in Arkansas. Their concerns sound familiar: lost species and less natural diversity, silting rivers, and economic hardships caused by overhunting.

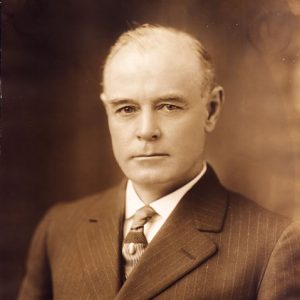

Important geological discoveries were being made. Bauxite mining began in 1898 in Saline County, and diamonds were discovered in 1906 in Murfreesboro (Pike County). The land of the Western Gulf Alluvial Plain and the Ouachita Mountains that had provided a first industry—the salt economy—for Native Americans would provide other mineral and chemical treasures, including bromide and ammonia. The hunt was on, with few penalties for damaging the environment. State geologist A. H. Purdue, writing in 1910, spoke out for conservation. He had already seen the negative effects of profligate coal mining in western Arkansas and of zinc and lead in northern Arkansas, and he cautioned, “In as much as some of our essential natural products are limited, the State should stand guardian over them for posterity.”

The twentieth century introduced the exploration of petroleum resources. The first gas well was drilled in western Arkansas in 1901, and, in 1920, Hunter Oil Company brought in the first producing oil well. Many of these fields have continued to produce steady if not remarkable quantities of oil and gas.

While Arkansas was trying to maximize its mineral assets and the lumber industry was systematically moving through the forests, William H. Fuller planted a new crop, rice, on the Grand Prairie in 1904. The 500,000-acre Grand Prairie on the Mississippi Alluvial Plain was distinguished by heavy clay subsoil, which Fuller believed would be outstanding for rice because it held water well. By 1905, 450 acres were in production. Since 1994, Arkansas has ranked first in rice production. In 2003, about 1.45 million acres was farmed in rice. Ironically, the success of rice is also at the heart of possibly Arkansas’s greatest environmental threat: the reduction of water in vital underground aquifers through the over-consumption of water, a concern that would have been difficult to visualize in the past.

Lack of water was certainly not a problem in 1927, the time of perhaps the greatest environmental disaster of the state, during which Arkansas’s environment was drastically affected by both nature and human activity. The Flood of 1927, caused by many weeks of record rainfall in the Midwest, as well levees that concentrated the flood waters, raised the Mississippi River well beyond flood stage, covering almost half of the state’s cropland (some two million acres) and destroyed thousands of miles of railroads, levees, county roads, bridges, and highways. Towns that had once been distant from the river washed away, while former river towns, such as Arkansas City (Desha County), ended up high and dry, away from the river. Principal crops, such as corn and cotton, withered. This loss promoted one positive result of the flood: The state began some of its first soil conservation efforts by planting alfalfa seeds provided by the federal government to rebuild the soil and prevent erosion. The flood, and floods following in the 1930s (especially in 1937), precipitated the 1937 Flood Control Act, and the first flood reservoirs were built on the White River, along with drainage and ditching projects in the Mississippi Delta.

On the heels of the Flood of 1927, record drought took the state into the Great Depression prematurely. The economic condition of the 1930s was relieved by the New Deal, which created the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the National Youth Administration (NYA), among other agencies that permanently changed the landscape of the state. As late as 1940, the WPA was still the largest employer in the state, with more than 33,000 employees. Workers built 11,417 miles of roads and forty-four parks. The parks system had begun in 1927 with the designation of the first state park, Petit Jean in Morrilton (Conway County). Mount Nebo State Park near Dardanelle (Yell County) followed in 1927. Crowley’s Ridge State Park near Paragould (Greene County) and Devil’s Den State Park near West Fork (Washington County) were designated in 1933. Many attractive examples of WPA cottages, lodges, and roads still exist in Arkansas’s state parks.

Initial attempts at environmental protection for species habitat had created the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission in 1914, but legislative and executive authority frequently overruled commission decisions. In an effort to take the commission out of the influence of politics, it became independent in its authority to regulate game law in 1944.

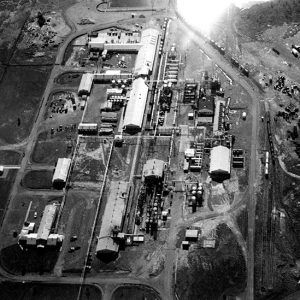

World War II caused significant changes in Arkansas’s environment, with greatly increased production of bauxite, the source of aluminum, and other war-related industries, such as ordnance and artillery plants, as well as puric acid and ammonia plants. The war also saw the creation or expansion of multiple military bases across the state. After the war, even with increased urbanization and diversification of agriculture, lumber, and manufacturing, the state suffered a significant emigration. In 1940, the population numbered 1,949,387; in 1960, it was 1,786,272.

Arkansas was growing not in population but in a new form of agribusiness—chickens. Centered in north Arkansas and the upper Arkansas River Valley, the poultry industry, which had started in the 1920s, had become big business. By the 1950s, Arkansas led the nation in production of broiler chickens. The industry thrives today, with a valued production of more than two billion dollars a year. However, along with creating 84,000 jobs, in the past half century, the industry also has created serious water and solid waste pollution problems, raising concerns about the environmental impact on streams in Arkansas and Oklahoma, especially the Illinois River.

In the 1960s, Arkansas benefited from a population influx. Attracted to the natural beauty and the low cost of living, two highly diverse groups sought new homes in Arkansas. The first was retirees, often attracted by planned communities, frequently associated with Corps of Engineers lakes on major rivers. The second might be called the back-to-the-land movement, generally composed of young people seeking a rural existence. Both groups contributed to the growth of north-central and northwest Arkansas, instruments in a corresponding economic boom. At the same time, the Delta, with its growing movement toward large, corporate farms, lost population as rural people, especially African Americans, moved to urban areas to work or left the state.

The opening of the McClellan-Kerr Navigation System on the Arkansas River in 1971 made the river navigable year-round from the Mississippi to the Port of Catoosa near Tulsa. Although the system did not prove to be the economic boon some hoped, it has contributed to flood control and improved water quality that have also resulted in population growth.

The introduction of interstate highways in Arkansas led to the creation of numerous trucking firms in the state, most notably J. B. Hunt. Created to haul rice husks from Arkansas County to the northwestern part of the state to be utilized in the poultry industry, the company now operates as one of the largest transportation logistics providers in North America. The interstate highway system changed the landscape of the state with the destruction of neighborhoods in cities like Little Rock to provide easier transportation from outlying areas, as seen in the construction of Interstate 630. The improved transportation helped fuel the depopulation of rural areas and increased urbanization in the state.

The Natural State

At the same time, tourism grew. The state attracted about fifteen million tourists in 1975. The influx of newcomers was not lost on state economic planners, and soon Arkansas had a new nickname: The Natural State. Environmentalists determined to make the name self-fulfilling, and a string of environmental victories followed.

In 1971, the legislature passed its first land reclamation acts, in effect saying to industry, “Put it back the way you found it.” For many years, the Soil Conservation Service had defended the land within agriculture mandates, and the Arkansas Oil and Gas Commission regulated drilling and exploration. In 1949, the Arkansas Pollution Control and Ecology Commission (in 1999 renamed the Department of Environmental Quality) was formed to police water and air, especially as those resources were affected by industrial development. This agency also established baseline water quality conditions and designated extraordinary resource waters. Many environmentalists consider designation of these extraordinary waters, identified as waters requiring the highest level of protection, one of Arkansas’s most significant regulatory achievements.

In a fight that attracted national attention, the Buffalo River was saved from development and designated a national river in 1972. In 1971, the Caney Creek and Upper Buffalo River Wilderness Areas were created. Nine more wilderness areas joined them in 1983. An attempt to construct Bell Foley Dam and create a reservoir on the Strawberry River was eventually defeated in 1977 with the veto of legislation by Governor David Pryor. An attempt to channelize the Cache River was abandoned in 1979, an event recognized even then as a major environmental coup and even more so a quarter of a century later when, in 2005, The Nature Conservancy of Arkansas announced the sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker, an environmental talisman considered extinct.

In 1973, the legislature created the Arkansas Environment Preservation Commission (now the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission) and a state system of natural areas, which number more than 100. Also in 1973, the Endangered Species Act was passed, saving the red-cockaded woodpecker by protecting existing habitat and providing for additional land. In 1980, conservationists won a major victory when the state Supreme Court ruled that they had the right to canoe the Mulberry River over the objections of some landowners along the river, a victory that extended the definition of “navigable” stream to include recreational boating. The decision had far-reaching effects for stream preservation.

By the mid-1980s, many community and regional advocacy groups—such as the Ozark Society, the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, the Sierra Club, the Ouachita Watch League, and the Newton County Wildlife Association—monitored environmental developments in poultry production, national forest planning, and Corps of Engineer proposals for ditching and damming. Arkansas benefited from land reclamation projects designated as Superfunds, the federal government’s program to clean up uncontrolled hazardous waste sites such as the Vertac site near Jacksonville (Pulaski County), which under various corporate ownerships had produced 28,440 drums of herbicide waste, as well as liquid and solid waste, landfill and burial areas of waste, and contaminated soils and buildings. An explosion at a military missile site in Van Buren County in 1980 led to an expansive cleanup effort that saw more than 100,000 gallons of contaminated water and tons of debris removed from the area.

In addition, the success of government agencies and non-profit organizations such as the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, The Nature Conservancy, and Arkansas Audubon in land, habitat, and species recovery is significant. Acres of land reclamation on former industrial sites, such as Alcoa’s bauxite works, and recovery of prairie or forest habitat testify to that success. In the 1990s, stronger laws for storage and disposal of solid waste, thousands of new acres in public ownership, and marked improvement in air quality in urban central Arkansas were evidence of environmental progress. Especially encouraging to nature enthusiasts was the willingness of citizens to tax themselves for improvements related to nature. In 1996, voters approved Amendment 75, a one-eighth percent sales tax that provided millions of dollars in funds for the Department of Parks and Tourism, the Game and Fish Commission, the Department of Arkansas Heritage, and the Keep Arkansas Beautiful Commission.

Troubled Waters

The considerable sprawl that has accompanied the growth in northwestern Arkansas during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries (causing land to be cleared for housing and for commercial and industrial growth) also brings air and solid waste pollution. The water pollution related to solid waste from the poultry industry, as well as the unchecked growth, has placed the state in an adversarial relationship with Oklahoma over phosphorus levels in mutual waterways. In June 2002, the Oklahoma attorney general filed a lawsuit against nine poultry companies with processing plants in northwest Arkansas or eastern Oklahoma, accusing them of polluting Oklahoma’s designated scenic rivers and the Illinois River watershed by exceeding phosphorus limits. The dispute has continued on into the 2020s.

In eastern Arkansas, in spite of cooperative efforts by government and non-profit conservation agencies in the development of the Cache River Refuge and others, the destruction of wetlands and woodlands in the Delta continued into the early twenty-first century. About 150,000 acres of Delta timberlands were cleared from 1995 to 2005. Less than one million of the original eight million acres of Mississippi River Delta bottomland forest remain in Arkansas. Only 2,000 of the original two million acres of prairie in the Delta remain unplowed. About thirty animal and plant species are extinct. The ever-increasing demand for agricultural water has begun to pollute and deplete the aquifers upon which surface waters depend.

In 1980, a Pollution Control and Ecology Department pamphlet described the Delta as “choked with silt, pesticides, herbicides. Water that once supported enough fish to supply a food processing industry is now rarely fished.” In northwestern Arkansas, the concentration of poultry production with the accompanying effects on fish, wildlife, and water has brought the state into court.

U.S. Forest Service roadless designation (which would limit timber cutting and road maintenance in certain areas) and commercial timber practices in the national forests, threats to the Lower White River and the aquifers, and continued gravel mining on Crooked Creek and other streams are just a few environmental issues making headlines. The creation of a commercial hog farm near the Buffalo National River in 2013 led to multiple lawsuits after the waste from the farm was found to be entering the watershed of the river. The state purchased the farm in 2019, and cleanup efforts continue.

None of these is more seriously debated than the question of additional removal of water from the White River basin and adjoining wetlands for agriculture. An Arkansas Geological Survey report on Water Resources of Arkansas, released in 1997, stated, “Because of water’s significance, any change or trend showing a decline in either the quantity or quality of the state’s water sources is of major importance. The increasing demand for ground water in eastern and southern Arkansas is a concern for many.” In 2005, the Arkansas Wildlife Federation, frequently the voice of hunters and fishers, filed its third lawsuit trying to halt the Army Corps of Engineers’ plan to remove water from the White River for irrigation.

An Enviable Position

Despite these concerns, Arkansas is in an enviable position in regard to its environment. Tourism based on the state’s natural beauty and the relative abundance of unspoiled wild and scenic places has been recognized as a significant economic plus. City and county solid waste facilities are now mandated, water quality standards are in place and improving, air quality is better, and the habitat of a majority of the state’s endangered species has been protected. Also, increased attention to public education and citizens’ willingness to pay taxes to preserve the environment are reaping tangible dividends. The worldwide attention the state received in 2005 for the alleged sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker provided impetus for more cooperative conservation planning, environmental-friendly tourism, and simple civic responsibility and pride. Early in the twenty-first century in Arkansas, the name “The Natural State” is not undeserved.

For additional information:

Anthony, Michael. “Geriatric Giants: Poisonous Leaks at Arkansas’s Titan II Facilities, 1974–1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Spring 2022): 46–67.

Bass, Sharon M. W. For the Trees: An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests, 1908–1978. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Forest Service, Southern Region, 1981. Revised, 1986.

Colten, Craig E. “Contesting Pollution in Dixie: The Case of Corney Creek.” Journal of Southern History 72 (August 2006): 605–634.

Dougan, Michael B. Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to Present. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1994.

Foster, Buckley T. So Great Was the Slaughter: Market Hunters, Sportsmen, and Wildlife Conservation in Arkansas. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2025.

Foti, Thomas, and Gerald Hanson. Arkansas and the Land. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Grove, Jama McMurtery. “‘Unjustified Expectations of Magic’: Arkansas Agricultural Specialists, DDT, and 2,4-D.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Summer 2020): 89–115.

Haddigan, Michael. “Is Arkansas Still a Natural?” Arkansas Times. November 20, 1998, p 10.

Hanson, Gerald, and Carl H. Moneyhon. Historical Atlas of Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

Harmon, Jeannie. “Prologue to Sprawl.” Arkansas Preservation Digest (Summer 2001): 2.

Holleman, John T. “In Arkansas Which Comes First, the Chicken or the Environment?” Tulane Environmental Law Journal 6 (1992): 23.

Key, Joseph P. “An Environmental History of the Quapaws, 1673–1803.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Winter 2020): 297–316.

———. “‘Masters of this Country’: The Quapaw and Environmental Change in Arkansas, 1673–1833.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas 2001.

Lancaster, Bob. Jungles of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1989.

Moore, Ramey Arlen. “Our Land Is Not Just Soil’: Knowing, Feeling, and Doing Environmental Activism in the Arkansas Ozarks.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2560/ (accessed November 27, 2024).

Oatsvall, Neil S. “Bottling Nature’s Elixir: The Mountain Valley Spring Water Company, Environment, Health, and Capitalism.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 78 (Spring 2019): 1–31.

Reynolds, Terry S. “A False Glimmer of Hope: The Rise and Fall of Arkansas’s Mercury Mining District, 1931-1946.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Winter 2022): 339–367.

River to Ridge: Arkansas’s Wildlife Management Areas. Little Rock: Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, 2025.

Shepherd, Bill, ed. Arkansas’s Natural Heritage. Little Rock: August House, 1984.

Steward, Dana F. A Rough Sort of Beauty: Reflections on the Natural Heritage of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Taylor, Steve. “Showdown on the Grand Prairie.” Arkansas Wildlife 31 (November/December 2000): 26–31.

Williams, C. Fred, S. Charles Bolton, Carl H. Moneyhon, and LeRoy T. Williams, eds. A Documentary History of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984.

Williams, C. Fred. Arkansas: The Land of Opportunity. Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, Inc., 1986.

Dana F. Steward

Sherwood, Arkansas

Revised 2024 by David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.