calsfoundation@cals.org

Van Buren County

| Region: | Northwest |

| County Seat: | Clinton |

| Established: | November 11, 1833 |

| Parent Counties: | Conway, Independence, Izard |

| Population: | 15,796 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 709.56 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

1,518 |

2,864 |

5,357 |

5,107 |

9,565 |

8,567 |

11,220 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

13,509 |

13,666 |

11,962 |

12,518 |

9,687 |

7,228 |

8,275 |

13,357 |

14,008 |

16,192 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17,295 |

15,796 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

14,485 |

91.7% |

| African American |

77 |

0.5% |

| American Indian |

133 |

0.8% |

| Asian |

56 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

0 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

200 |

1.3% |

| Two or More Races |

845 |

5.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

501 |

3.2% |

| Population Density |

22.3 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$38,499 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$22,168 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

18.5% |

|

Formed in 1833, Van Buren became the twenty-ninth county in Arkansas Territory and preceded statehood by three years.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The area that is now Van Buren County, in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains, has been inhabited for roughly 10,000 years. Osage and Cherokee Indians were the first historic Native American tribes known to have a connection to the area. Hunters from Ozark villages in southwestern Missouri, and later in northeastern Oklahoma, often visited the area, although they had no permanent settlements in the county. No official records are available to tell who the first European or American settlers were or where they came from, but indications are that they began making their way into the hill county in the1820s, settling in the area south of the Little Red River.

Perhaps the most important settler in this part of the county was John L. Lafferty, who came to Arkansas from Georgia. Lafferty owned a large plantation near where the three branches of the Little Red once ran together. This area, now covered by Greers Ferry Lake, was once known as “The Big Bottoms” and contained rich farmland. Lafferty was the guiding force in the creation of Van Buren County. Although these lands were parts of other counties at the time, the growing settlements in the area and the great distances to the other county seats necessitated a more localized government. Through Lafferty’s efforts, Van Buren became a county on November 11, 1833. The county’s namesake was Vice President Martin Van Buren; it is not known why.

The first county seat was Mudtown—so named because any appreciable amount of rain resulted in ankle-deep muddy streets. Mudtown later became known as Bloomington. This community was near Lafferty’s home, and the county’s business was conducted in the home of Obadiah Marsh. Soon after the county’s formation, a one-room log structure, constructed by the men in the community in a “log raising,” served as the courthouse.

The 1830s brought more families to the area, and, by 1840, the county had 243 families with a population of just over 1,500. Ten years later, 448 families were documented as living in the county, and the population had reached 2,864.

Van Buren County is hilly and rocky, few economic opportunities existed, and the area was far removed from the main transportation arteries. These factors diminished the interest of many prospective settlers heading west in the early 1800s. Settlers began migrating to the area only when the government made land available at attractive prices after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Most of the initial newcomers came from the Carolinas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee.

Migration into the area increased when Arkansas became a state in 1836. Statehood may have made this wilderness area seem a little more acceptable to settlers. Also, a financial panic swept across the nation in 1837, and many families lost their farms and most of their possessions. Families looking for a new start loaded their wagons and headed west.

The new migrants cleared timber and carved out portions of land to begin farming. These were usually small farms where cotton, corn, potatoes, oats, wheat, and tobacco were grown. Sheep were raised for the wool, and swine for meat. Family members tended most of these farming plots, but the 1850 census included 103 slaves in addition to the 448 white families in the county.

The county seat was moved to Clinton in 1842, and again a log-raising event produced a one-room courthouse. Several years later, a two-story white frame columned courthouse replaced the log structure.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

The 1860 federal census recorded the white population in the county at 5,157 and the number of enslaved African Americans at 200. James Patterson, the owner of two enslaved people at the time of the 1860 census, represented the county at the 1861 Arkansas Secession Convention.

County residents were divided in their loyalties to the North and the South in the Civil War. Many anti-secessionists were found in the hill country of Van Buren and surrounding counties. When the fighting broke out in 1861, there was pressure to support the Confederacy, with many local men joining area Confederate regiments, but others joined a secret peace society. Some of the members were Union supporters. Others were just looking for a way to protect their families and belongings from roving bands of guerrillas who raided, burned, and killed throughout the area. Some of these guerrillas had Unionist leanings, but many were just taking advantage of the lack of law and order prevalent at the time. Members of the peace society were arrested and given the choice of joining the Confederate army or being tried for treason.

Irregular groups of supporters of both the North and the South were the primary perpetrators of the violence in Van Buren County. Bushwhackers burned the courthouse in 1865. The local Methodist church was used as a makeshift courthouse until a new two-story frame courthouse was erected in 1869.

The court case United States v. Waddell et al. reached the United States Supreme Court in 1884. The case began the previous year in Van Buren County when white residents tried to force an African American homesteader from his land.

Three white men were lynched in Van Buren County in 1894 for allegedly attacking and robbing an elderly couple. Few details exist on the incident.

Early Twentieth Century through the Modern Era

The county saw little industry or economic development until 1910, when the Missouri and North Arkansas (M&NA) Railroad came through and established a depot in the settlement of Shirley. This opened markets for merchants and farmers and especially for owners of virgin timberland. Shirley became the hub of the timber industry. Small-scale sawmills and timber operations existed before, but the railroad provided an efficient way to transport timber to large markets. The Shirley area initially prospered from the railroad, and the county’s population continued to grow slowly until the 1940s.

The Great Depression affected citizens in the county as it did in other parts of the state. Little money circulated, and a bartering system emerged. Farmers traded eggs and poultry to merchants for staples such as sugar and flour, and doctors were paid with whatever a farmer had to offer.

Programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the National Youth Administration (NYA), and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided work and education in the economically depressed area. Many school buildings were constructed during the existence of these programs, and the county’s present native stone courthouse was constructed with the WPA’s assistance in 1934. The WPA also supported the construction of Van Buren County 2E Bridge. Two CCC camps were organized in Van Buren County—Lost Corner, near the Van Buren–Conway county line, and Damascus, on the Van Buren–Faulkner county line. These programs not only provided employment for area men but taught farmers a new way of terracing crops to avoid soil erosion. The location of the Damascus camp was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the 1940s, in the aftermath of the Depression, people left the county in droves, an exodus that continued until 1960. The decreasing demand for cotton and the increasing need for fertilizer and insecticides drove most of the marginally profitable farms below the subsistence level, and many farmers left the area to look for work. During World War II, many people went to work in the defense industries in the North and on the Gulf Coast and the West Coast. At the end of the war, some returning veterans joined their families who had moved out west and up north to work in automotive plants.

About fifty African American families joined the exodus, and, after 1960, only nine Black families remained in the county. By 1969, none were actively farming, which had been their principal occupation.

The U.S. Department of Defense developed eighteen missile silos in Van Buren and surrounding counties in the 1950s and 1960s. Housing Titan II missiles, the sites were staffed by members of the United States Air Force. An explosion at a missile site in Van Buren County in 1980 led to the death of one airman.

In 1949, the M&NA abandoned operations in the county because of the dwindling supply of timber, removing the last major deterrent to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ plans to erect a dam across the Little Red River to control flooding and generate hydroelectric power. Construction began just east of Heber Springs (Cleburne County) in March 1959 and was completed in 1962. The resulting Greers Ferry Lake, a major tourist attraction, extends about thirty-five miles west of the dam to Choctaw.

The lake brought many changes to the county. It displaced families and cemeteries, and it covered the villages of Choctaw and Eglantine, as well as the rich bottom land along Choctaw Creek and the South Fork of the Little Red River. But much of the money from the government’s purchase of the land was reinvested in the county in the form of land purchases and business opportunities. The lake also brought recreational opportunities, additional residents and visitors, and increased land values.

In 1966, the first houses were built in the lakeside development of Fairfield Bay, which became a popular retirement community. It lies mostly in Van Buren County and partly in Cleburne County. The influx of residents drawn to this community helped increase the county’s population significantly in the 1970s and 1980s.

The film Terror at Black Falls, released in 1962, was filmed in the county in 1959.

Attractions

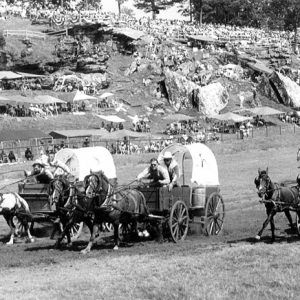

Along with the lake and the scenic hills, the National Championship Chuckwagon Races have become a tourist attraction. What began in 1985 as an eight-team race between friends at Dan Eoff’s ranch west of Clinton grew into a major Labor Day event. Besides the races, the event began offering shooting exhibitions, trail rides, cowboy clinics, music, dances, vendors, and food. More than one hundred teams regularly attend the event, which attracts thousands of spectators.

South Fork Nature Center is located just east of Clinton and is operated by the Gates-Rogers Foundation.

Locations in the county listed on the National Register of Historic Places include the Damascus Gymnasium and the courthouse.

Famous residents of the county include educator William Halbrook, bandleader Opie Cates, baseball player Sue Kidd, and Charles Wayman Hogue, author of Back Yonder, An Ozark Chronicle.

For additional information:

Clark, Ruby Neal, ed. A History of Van Buren County, Arkansas. Conway, AR: River Road Press, 1976.

Van Buren County Historical Journal. Clinton, AR: Van Buren County Historical Society (1984–).

Van Buren County Historical Society. A Pictorial History of Van Buren County, Arkansas: Memories of a Century, 1890–1990. Marceline, MO: Heritage House Publishing Co., 1990.

Sharon Baker

Van Buren County Historical Society

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.