calsfoundation@cals.org

Recreation and Sports

Recreation and sports have long been vital to Arkansas. Recreation has been important in Arkansas since prehistoric times, and sports also have a long prehistoric as well as historic component.

RECREATION

We can only guess at the nature of recreation during the more than ten thousand years of habitation before the first Europeans arrived. The modern and Euro-centric term “recreation” very inadequately defines what tribes practiced. Dancing, for example, was a main component of Caddo Native American culture, but in addition to its elements of immediate enjoyment, it transmitted traditions and practices to upcoming generations.

European settlement of Arkansas began with the French explorers, and judging by the observations of outsiders, entertainment provided by the Quapaw and other local tribes, such as juggling and feats of swallowing, remained important.

Fighting

Although called assault and battery in the common law, fighting was both a common test of manhood and a recreation on the Southern frontier. Hunters, a rather primitive class for the most part, shared in the customs of personal violence; biting off ears and noses, gouging out eyes, and participating in boxing matches that lasted until one of the parties was dead or all but dead were considered normal entertainment.

Music and Dancing

The French loved music and dancing. Some thirty years after the Louisiana Purchase, noted writer Washington Irving thought he heard an old French chanson while visiting Arkansas Post. Scandalizing conservative Christians, the French held dances on Saturday nights.

American settlers brought many traditional dance forms to Arkansas. The Virginia Reel, for example, was both a special dance as well as the name of one popular dance tune—“Miss McLeod’s or The Virginia Reel”—which, like many other dance tunes, was available by the early nineteenth century on sheet music. Another dance tune, “The Arkansas Traveler,” rose to prominence in the 1840s. A triptych arose that included the tune itself, the story of the lost traveler who delights the squatter by being able to play the second section of the tune, and the painting by Edward Payson Washbourne, the state’s first native-born painter of prominence. Tom Shiras, a noted Mountain Home (Baxter County) editor of the early twentieth century, believed “Soldiers Joy” ranked first in popularity in the early twentieth century. Fiddle players provided the music for these dances. Hence, the fiddle was considered by evangelicals as the devil’s own instrument. Because often only one player was available and the crowds were large, the player placed the instrument against the side of his body in order to produce more volume. “We had some oald back down dances on the dirt floar and if any of us lost aney toe nales, thare never was a any thing said about it,” one early hunter recalled. Dancing of a more refined variety also took place in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and even Fayetteville (Washington County). These society events utilized formal invitations, orchestras, and the presence of persons who had actually had dancing lessons. The polka and the schottische led in popularity. Arkansan Ferdinand Zellner’s “Fayetteville Polka” was published in 1856. The waltz, which involved more direct bodily contact, grew in popularity as the century wore on. Conservatives banned all recreational music. In rural areas, singing schools arose, using shape notes. The tunes were traditional, and texts were generally religious in nature.

Religious opposition to dancing remained strong among some conservative Protestant denominations. Many town ordinances banned public dancing, and some high school proms were not held in some smaller rural districts. Opposition to dancing in general focused on whatever form was currently popular. Hence, by the twentieth century, the waltz had attained respectability, in part because the Charleston and black bottom were considered vulgar and linked with both alcohol consumption and sex.

Hunting

Hunting underwent a transformation during the nineteenth century as professional hunters gave way to sportsmen. The early American elite joined in the hunt, and in the southwest part of the state, Sixth Circuit Judge George Conway (who presided from 1844 to 1849) would adjourn court in an instant upon receiving a report that a bear had been sighted. A major sport in the nineteenth century consisted of passenger pigeon–killing contests. Massive slaughter followed the Civil War, but locals refused to accept responsibility for the birds’ extinction, claiming instead that the flocks drowned in the Gulf of Mexico. With the depletion in short order of bears, elk, bison, Carolina parakeets, and other animals, hunters turned to more prosaic local animals. “Varmints,” as they were commonly called, in the form of raccoons, formed the basis for one of Arkansas’s most enduring political spectacles: the Gillett Coon Supper in Arkansas County. Established in 1947, this event is still going strong and attracting political powerhouses from all over Arkansas. Feral hogs were considered a capital sport; they can still be hunted in Arkansas, and there are no seasonal limits. Rabbits and squirrels, the former known during the Depression as “Hoover Hogs,” helped sustain families during hard times.

The culture of hunting centered around hunting camps. The first recorded instance, reported by the French explorers Marquette and Joliet on their map and subsequently confirmed by archaeologists, was an encampment of the Illinois Indians on the upper Black River. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century camps were notorious for the amount of alcohol consumed. Arkansas’s first prime camp chef was Albert Pike, whose Arkansas version of a Brunswick Stew was well remembered.

Most pre–Civil War hunting by common people was with shotguns because rifles were prohibitively expensive. The mass production of weapons during the Civil War removed the financial barrier. Hunting camps were typically male-only events that at night featured much food and strong drink. After 1970, tents gave way to ever more elaborate campers. Although many Arkansans could not afford expensive firearms, they did take pride in their dogs. Grayson White v. Alfred Scott (1922) in Searcy County was Arkansas’s great dog case, in which a local justice of the peace had to rule on whether some speckled hounds were “good dogs”—meaning that they would not hunt rabbits at night. The case was settled out of court.

In 1915, the legislature created the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, giving it enforcement in all the state’s seventy-five counties. State senator J. Marion Futrell of Paragould in Greene County (a former acting and future governor) authored the legislation and pushed it through. Rules and regulations were established and active enforcement began. To aid in education, the commission began publishing a magazine in 1924 first titled, The Arkansas Deer. It became The Arkansas Conservationist the same year but fell victim to the Depression in 1931. It was being revived in 1967 under the title Arkansas Wildlife. Amendment 35 (1944) made the commission an independent agency. In November 1996, voters approved a one-eighth of one percent addition to the state sales tax earmarked for conservation.

The return of game to Arkansas after 1940 was the result of enforcement of state regulations; state restocking programs for deer, bears, turkeys, and elk; and more habitat when massive land abandonment came in the wake of out-migration. Deer benefited most by this, but the bald eagle—not a legally huntable fowl—was saved from extinction by environmental laws banning a number of toxic chemicals. The resurgence of the animals fueled more hunting. By 2005, deer outnumbered people in a number of counties. The richer hunters secured leased hunting lands, especially in south Arkansas where ownership rested with large timber companies. As the right to hunt increasingly became defined by one’s economic status, those priced out of the best land turned to trespassing and out-of-season hunting.

Hunting season begins in the fall with mourning and turtle doves; more than half a million are killed yearly. This bird readily adapted to suburban and urban environments, but the same was not true with quail, whose numbers have been halved since 1980. Reasons for the decline include the destruction of habitat due to land clearing and pastures planted in fescue, over-hunting, and an increase in coyotes and other predators. After many experiments with restocking, wild turkeys staged a comeback after 1948. Habitat loss, in part due to prolonged drought, affected duck and other waterfowl hunting. Duck hunting was championed by a private group, Ducks Unlimited.

The significance of hunting in Arkansas’s culture cannot be underestimated. Thousands of Arkansans holding jobs out of state demand the right to be free to return home “to get their deer.” They will quit a high-paying job rather than sacrifice what they consider a basic right. The National Rifle Association (NRA) draws strong support in Arkansas from the hunter class. The once-important, God-ordained “blue laws” of the nineteenth century that banned hunting and fishing on Sundays became completely forgotten.

Tourism has also played a major role in hunting. It was tourist-hunters and fishermen who demanded game laws to stop the promiscuous destruction being carried out by the local residents. The leading Supreme Court case regarding a federal treaty with Canada to protect migratory birds, Missouri v. Holland (1920), included overturning an Arkansas case decided by Judge Jacob Trieber in the Eastern District of Arkansas. The decision upheld the federal government’s superior powers under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, protecting both the hunters and migratory birds from Arkansas residents. Tourist hunters were most drawn to eastern Arkansas. Stuttgart (Arkansas County) was famous for its duck hunts, and beer baron August Busch of St. Louis, Missouri, was a frequent visitor.

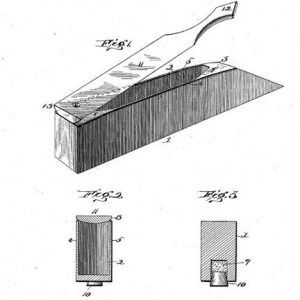

Besides establishing a special season for black-powder hunters, state regulations also encouraged bow-and-arrow hunting. Arkansas was internationally noted for the Ben Pearson Company of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), which began making archery equipment before 1940. Atlatl hunting for deer has not yet returned to modern-day Arkansas, although it is practiced in Alabama, Alaska, and Pennsylvania.

Fishing

Archaeological evidence plainly indicates that fish were probably more prominent in the diet of early Americans than red meat. Fishing in nineteenth-century Arkansas began in earnest in the 1850s, precisely at the time when much formerly plentiful game no longer existed.

Several types of fishing existed in Arkansas. Some people—who relied heavily on selling fish—used skeins, poisons, and electric generators to kill or stun fish. Country people made fishing a family outing in which the fishing was secondary to the socializing. Bait consisted of worms (catalpa worms for catfish, night crawlers if you could find them), minnows, and crayfish. The best crayfish—“crawdads” in local parlance—were those in the process of shedding their shells. Other special baits, often fortified with a family formula of fish blood and guts, were used for catfish. Some locals and many outside visitors were committed to artificial lures. Fly-fishing has always been a “gentleman’s sport.” The best rods came from China, and serious students tied their own flies.

While most fishing was done from the banks, long wooden johnboats were deployed on streams all over the state. Trot lines, jugs, and other passive fishing forms utilized boats. Virtually every stream in Arkansas had, where feasible, well-maintained trails along both banks. The best fishing holes had names, and country people used cane poles and made their own hooks and cotton line until after the Civil War. In days before both damming and large-scale cattle culture, the White River was so clear that people standing on a bluff could count the fish in the water. Such water was treacherous to wade in because it was impossible to tell how deep the water might be even though every rock could be seen clearly. This eventually invited fishing with .22 caliber rifles.

The White River and its various tributary streams were so highly valued that one local economic activity consisted of providing guides to tourist sportsmen. The guide usually provided the boats and supplies, took the fishermen to the best spots, and at night set up camp and fixed the food. Gravel-bar coffee and an enormous breakfast followed in the evening by fish fried in cornbread were culinary highlights even if the fish were not biting. Family outings, often lasting a week, became increasingly popular after 1890. While female hunters were rare, fisherwomen were common.

Hunting and fishing newspapers had appeared even before the Civil War, and the outdoor stories of Charles Fenton Mercer Noland, Albert Pike, and William Minor Quesenbury were read nationally. Monthly magazines devoted to outdoor sports circulated nationally by the early twentieth century.

By 1923, Mountain Home editor Tom Shiras pointed out that fishing waters had become greatly depleted. Stringent enforcement was needed against dynamiting and gigging game fish, and spawning season in the spring needed to be protected. Editors, sporting magazines, and state publications tried thereafter to educate people in conservation.

Two important changes came to fishing in the twentieth century. The first was the introduction of the outboard motor. The first practical American outboard was the work of Cameron B. Waterman. Three thousand of his machines were built in 1907, but it was not recorded whether any of them reached Arkansas. More successful was Ole Evinrude, who began production in 1909. Improvements continued apace, and by the 1930s, Sears and Roebuck sold art deco–designed machines at low prices.

Outboard motors had limited use on smaller fishing streams. Besides making too much noise, they stirred up the water and scared the fish. Fishermen on the banks were disturbed by the passage of motorized craft. Some fishermen used them to get in the vicinity of a good spot but then relied on paddling during the fishing session. The machines did allow fishermen to go upstream easily.

The second change was the damming of the free-running streams to create lakes. Non-native fish species were introduced into Arkansas. The White River below Norfork Dam became a trout mecca. Walleye, northern pike, and striped bass came into the state, and fishing for sport became more important than fishing for food.

Channelization in the Delta and damming in the Ozarks and Ouachitas destroyed traditional fishing almost entirely. Two waterways that escaped this fate were the Buffalo River and the Strawberry River. The crusade to save the Buffalo captured national attention and ended when Congress in 1972 turned it into a national river, the water equivalent of a national park.

By the twenty-first century, fishing had become almost completely boat centered, and bass boats emerged as luxury items. Monarch was one early Arkansas manufacturer, and with growing technological sophistication, little in fishing was left to skill or luck. Bass tournaments dominated the sport, and the investment in boats was matched by rewards of upwards of $500,000 from winning these contests.

Recreational fishing on lakes conflicted with water sports, notably water-skiing, which became increasingly popular after 1960. During the summer, lake fishing was limited to the coves. By the early twenty-first century, pollution was on the rise, lakes and streams were slowly dying, and the purchase of fishing licenses had gone stagnant along with the water. But the lakes were a major tourist attraction for water-skiing and scuba-diving, and many retirees from northern states decided to settle around the lakes. New communities, such as Hot Springs Village, Fairfield Bay, and Bull Shoals emerged, and older towns, notably Mountain Home and Heber Springs, were transformed by immigrants.

Fort Smith (Sebastian County) is home to PRADCO (Plastic Research and Development Company), one of the nation’s largest artificial lure manufacturer, whose brand names included Heddon, Abrogast, and Cotton Cordell, the last being named for a Hot Springs (Garland County) craftsman.

Other Recreation

Arkansans relish horse racing. Pure-bred stock arrived during the 1830s, largely through the efforts of Thomas Tunstall. But the sport suffered a severe setback when the Depression of 1839 financially ruined many of the participants. Churches, a growing force by the 1840s, opposed the gambling associated with the sport. Hot Springs, a medicinal center turned tourist town, sported every variety of sin, and despite being in a hostile state, managed to get its track, Oaklawn Park (now Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort), legalized in 1904. The distribution of free passes helped keep the legislators friendly.

Bird tourism soared in 2005 when an ivory-billed woodpecker (once thought to be extinct) was supposedly sighted in eastern Arkansas. Eagles winter in Arkansas as well, giving bird watchers added reasons to visit.

The major provider of recreational opportunities is the State of Arkansas, with fifty-two state parks. Many of these are nature-oriented. Arkansas features prominent hiking trails, such as the one through the Ouachitas and the one through the Ozarks. When adequate water levels permit, the Buffalo National River is jammed with canoes.

SPORTS

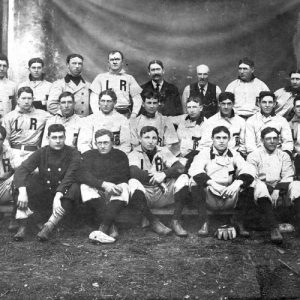

Sports, especially ball games, were important aspects of early Arkansas culture. The best-known example of “Indian ball” was recorded from the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory in Oklahoma, but Arkansas tribes likely participated in similar activities. Indian ball continued throughout most of the nineteenth century, and displays were put on for tourists, although by that time the participants wore clothes.

Sports on the early frontier reflected the establishment and maintenance of a social order based on violence. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, numerous forces tried to limit, control, and sublimate the excesses. A rising middle class with leisure time began imposing rules that limited violence. Groups such as the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and parallel groups for women popularized both physical fitness and orderly play. Henry Bergh, the founder of both the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) and a parallel organization to protect children, led the Victorian charge against “pistol toters,” wife beaters, cock fights, and the near universal brutality then practiced on animals in the name of sports. ASPCA found support from the Arkansas legislature and in 1879 was given policing powers under legislation that is still in existence. Finally, Arkansas’s growing population after the Civil War and a system of rail lines that tied Arkansas ever closer to the national scene provided a basis for the emergence of group sporting activities. Local stores began to stock sporting goods, and the national firm of Peck & Synder offered an extensive catalogue of sporting equipment.

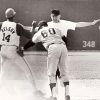

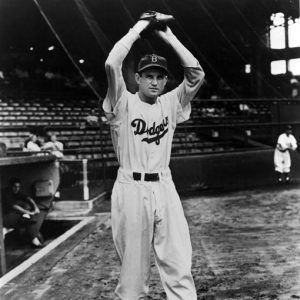

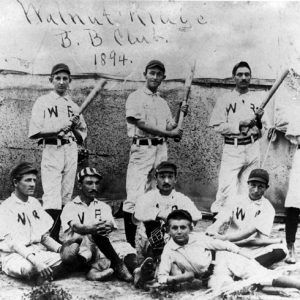

Baseball

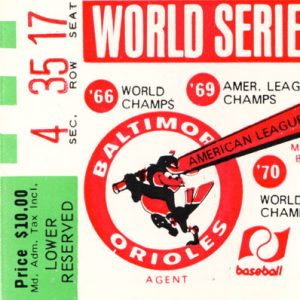

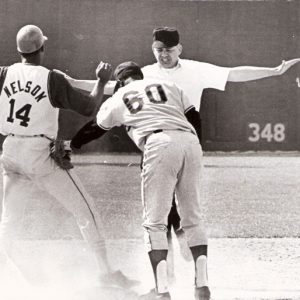

The first official game to emerge in Arkansas was baseball. Popularized by the Union army during and immediately after the Civil War, it built on well-established town-ball skills and practices. Teams flourished by the late 1860s, although one calling itself the Ku Klux Klan was arrested by an utterly unsympathetic Sebastian County Republican sheriff. By the time of the American Centennial in 1876, baseball had become America’s sport. At picnics and county fairs, especially on the Fourth of July, fields were roped off, and deputized police prevented rowdiness. Accompanied by competing town bands, teams squared off. The equipment was simple and often homemade, but games were played with a vengeance. Editor Cicero Brown at the Marshall Republican even used the crowing rooster, normally reserved for election victories, to report Marshall’s (Searcy County) 38-8 victory over Valley Spring (Boone County).

Helena (Phillips County) shut down when its team played Friars Point, Mississippi. Citizens boarded a chartered steamboat and, accompanied by the town band, went down to watch their Mississippi opponents get a good licking. Losses were often blamed on the umpires, and one active “ump” in northeast Arkansas avoided serious disputes by wearing a pistol openly. These teams sported flexible rosters, and in the late fall after the major league baseball season had ended, towns eager to win hired “ringers” to substitute for the locals.

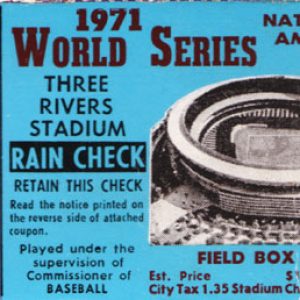

Town ball continued to thrive until undermined first by radio broadcasts of major league games and then by television. By the early twentieth century, organized local leagues, patterned on the National and American Leagues, provided some stability. These minor league clubs traveled by bus to towns within a roughly 100-mile radius. One of the most colorful was the Arkansas-Missouri League (1936–1940). Local sponsors provided the funding. A step up was the often-reorganized Cotton States League (1902–1955) that flourished in medium-sized towns in South Arkansas and adjacent states. Its demise came in part because the region’s white population preferred to shut down baseball rather than integrate.

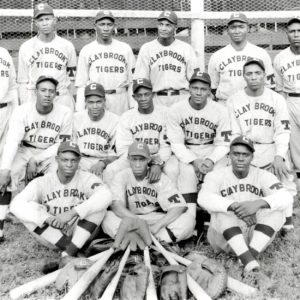

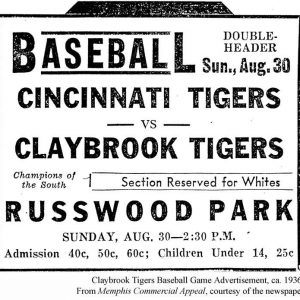

In the age of segregation, Arkansas’s African American community formed its own teams. All-star teams occasionally played against whites. In Crittenden County, Black entrepreneur John Claybrook founded his own team, the Claybrook Tigers, in 1929. He hired quality Black players, including Ted “Double Duty” Ratcliff, who would pitch the first game and catch the second in double-headers.

Most enduring was the franchise in Little Rock known as the Little Rock or Arkansas Travelers. After joining the Southern Association in 1901, the team became defunct between 1910 and 1914. In the troubled post–World War II era, no teams were fielded in 1959 and 1962. The 1963 team featured Dick (“Richie) Allen, the team’s first Black player. Allen, who did not grow up in the South, did not recall his Arkansas days—in which he felt like he lived in isolation, subject to the double standards of the day—with fondness.

By 1966, the franchise had become a member of the Texas League. In 1960, continuity was ensured when the team became stockholder owned. Especially revered for keeping baseball in Little Rock was Ray Winder, who for more than thirty years worked tirelessly in support of a minor league in Little Rock. The team’s stadium, which opened in 1932, was renamed Ray Winder Field in his honor in 1966. The final game hosted at Ray Winder Field took place on September 3, 2006. On April 5, 2007, the Travelers opened their new ballpark, Dickey-Stephens Field, in North Little Rock (Pulaski County).

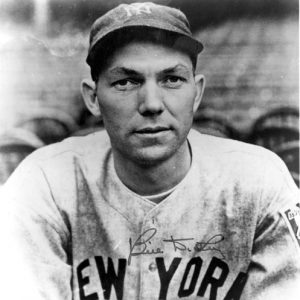

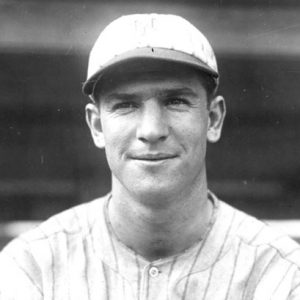

Although minor league baseball existed in the twentieth century only because of working agreements with major league clubs, and roster changes made it difficult for teams to establish continuity and a strong fan base, every minor league team depended on established regulars who were not likely to advance upward. The first of these “franchise” players was probably Rube Robinson from Searcy (White County), a left-handed pitcher and team member starting in 1916 and then for the next thirteen years, who threw “slow, slower, and still slower,” Jim Bailey recalled. During the 1960s and 1970s, John (Duke) Young, “a not-too-agile, not-overly-trim first baseman,” was famous for his homeruns.

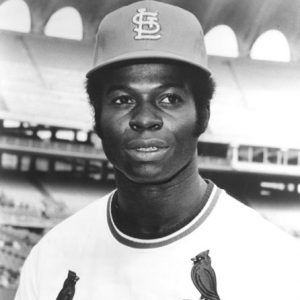

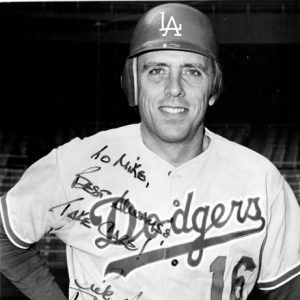

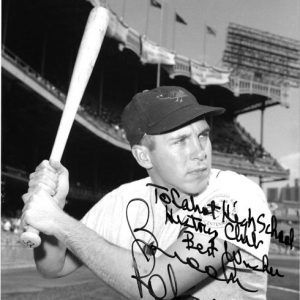

Arkansas has provided six major league players to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Despite the fact that he left the state while still a child, Joseph Floyd Vaughan of Clifty (Madison County) was nicknamed “Arky.” Lou Brock from El Dorado (Union County) also left the state, and Jay Hanna “Dizzy” Dean from Lucas (Logan County) was another short-time Arkansas resident. Three Hall of Famers did return to the state: Travis Jackson was born and died in Waldo (Columbia County), George Kell of Swifton (Jackson County) returned to become an automobile dealer in Newport, and Little Rock’s Brooks Robinson remained active in sport circles. Arkansas baseball figured prominently in Donald Hays’s noted novel, The Dixie Association (1984).

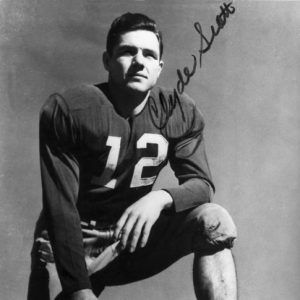

Football

Football grew out of the English game of rugby and represented raw group power much more than baseball’s combination of individual and group talent. Its formal appearance in Arkansas came on New Year’s Day, 1892, with a game between the Little Rock YMCA and Little Rock Commercial College. The cream of local society—led by the governor’s wife, Mrs. James P. Eagle—graced the occasion, appearing in highly decorated fashion. During the next few years, towns tried to develop teams along the same lines baseball had taken. However, getting the eleven players together proved an insurmountable problem. Baseball players could practice their skills individually or in small groups; football virtually required the whole team be present to practice. The final blow to the town model was the Panic of 1893 and subsequent depression that robbed towns of workers with both income and leisure time.

The first collegiate game was between Little Rock Academy and a Hendrix College (Conway) team composed of professors and students. After the academy won, and one of the professors had been injured, a Hendrix student declared football should be abolished since “the life and limb of the player is in constant danger.” Nevertheless, other colleges hastened to form teams. Arkansas Industrial University showed its lack of industry by losing to the University of Texas 54-0 in 1894; the Cardinals (who became Razorbacks in 1910) demonstrated their supremacy locally by repeatedly defeating Fort Smith High School and some very obscure colleges in Missouri.

Meanwhile, as the sport grew in popularity and took root in high schools, techniques like the flying wedge resulted in an increasing loss of life as well as of limb. “Manslaughter misnamed sport,” the Arkadelphia Southern Standard called it in 1897. George C. Millar, while playing a game at Hendrix College in 1892 (where his brother, Alexander Copeland Millar was president), was “smashed in the root of his organ of smell.” He later suffered a broken leg while playing the game. The leg became cancerous, and he died from the cancer three days after his marriage, thus becoming the first known football death in Arkansas. Nationwide, there were thirty-three playing-field deaths in 1908. In 1910, rule changes were finally enacted (never completely enforced or universally recognized) in an attempt to limit the mayhem.

Another issue of concern involved education. The first coach (who coached from 1894 to 1896) at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville, John Clinton Futrall, was also a Latin teacher and future president of the university. Having a faculty member as coach gave the game the school’s recognition and status, but it also led to criticism from the Arkansas Gazette. Reflective of the commercialism that early on marked the game, Fayetteville was paid $400 to go play the University of Texas, where they lost badly. The first “professional” coach was Hugo Bezdek, a former student and player under Amos Alonzo Stagg.

Although a few critics claimed the rising professionalism threatened academic study, probably the most commonly held view was that sports led to character development. “No young man is fit to go out into the world unless he knows how to put up a clean fight,” Mountain Home editor Tom Shiras asserted.

After 1900, “ringers” became common. The apparent first was Jewell Larkin “Nick” Carter who in 1913, after leading the Razorbacks to victory over Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University), was lured away with the promise of money to play for Ouachita. He repaid the debt by helping his new team defeat his old one. A different sort of “ringer,” who might be described as Arkansas’s first “jock,” was Herbert Y. Fishback, son of the former governor, who proved to be a star player with a less-than-stellar academic record.

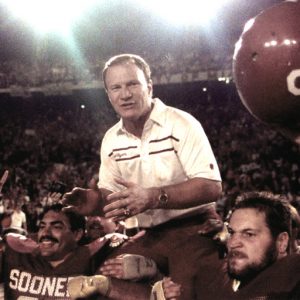

By 1912, two important elements associated with football and education had solidified. First, colleges took over and managed football programs with a view to making money and advertising their schools. In the process, UA solidified its state-wide presence by coming to Little Rock for some of the games. Second, athleticism spread into the public schools, arriving at the same time as compulsory attendance laws. Coaches, whose salaries were based on the success of their teams, often put winning first and any educational values far to the rear. As football’s popularity expanded after World War II, college coaches not only commanded salaries equal to or exceeding that of school presidents but also received a wide range of private favors, from houses to cars. High school coaches remained nominally teachers, but typically they taught subjects such as social studies, where their neglect of non-athletic students became legendary.

A statewide ritual known as “calling the Hogs” started in the 1920s and accompanied the ups and downs of the Razorbacks. By the end of the twentieth century, luxury boxes and very elaborate pre-game (and post-game) parties formed the basis for hard-core fiscal and even political support. Ruling over this world was Razorbacks coach Frank Broyles, who was so politically protected that he could dictate policy to the university.

The “Game of the Century” for Razorback football came in 1969, subtitled in Terry Frei’s book as “Dixie’s Land Stand,” alluding to the fact that all the players for Arkansas and Texas were, for the last time, white. President Richard M. Nixon flew into Fayetteville along with evangelist Billy Graham and former Razorback All-American Senator J. William Fulbright, who later visited the losing Hogs in their locker room. The comment of one player, Bill Burnett, “I just blew it,” reflected for some the bittersweet nature of Arkansas’s legendary failures.

In the late twentieth century, Arkansas State University fielded a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division 1A football team over the opposition of the University of Arkansas, which, under Coach Frank Broyles, made it clear that Fayetteville would never again play an in-state rival. Athletic deficits, running into the millions of dollars, haunted the state’s various athletic programs.

Arkansas was too small of a market for professional football, although Arkansas did field a pro-football team, the Arkansas Diamonds, that played in 1968 and 1969 in the Continental Football League. The league folded in 1969. The Arkansas Twisters competed in the Arena 2 Football League from 2000 to 2009.

Basketball

Basketball was invented in 1891 by James Naismith, and in 1892 the first rules were published and play began, using soccer balls at first. Intended for indoor recreation and possibly for good exercise for baseball players, the sport took on a life of its own, reaching the collegiate level in the 1920s. In towns, the local YMCA invariably added a basketball court, and town leagues soon formed to compete against each other. In rural schools, dirt courts, sometimes spread with gravel if the ground was wet, were the rule. High school basketball benefited greatly from the Depression when federal dollars and WPA workers built multi-purpose buildings that included a cafeteria, gym, and auditorium. Those hardwood floors became sacred, and gym shoes became another expense students had to bear.

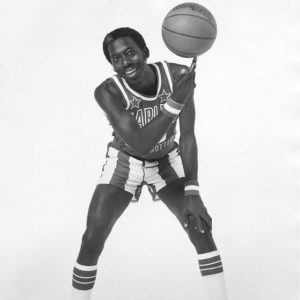

After World War II, touring teams, such as the Harlem Globetrotters, made their way into Arkansas, thus showcasing Hubert Eugene “Geese” Ausbie, “The Clown Prince of Basketball” and former Philander Smith College star. After 1957, the collapse of segregation opened the doors for talented Black players. UA had a nationally known coach in Nolan Richardson, who in 1994 brought home a national championship. However, his tenure was controversial and ended with his firing in 2002.

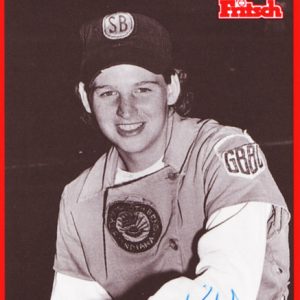

In contrast to baseball and football, basketball was also played by female athletes. Girls’ basketball, played on a half court, was highly popular in rural schools across the Midwest and South, and it flourished as well on the college level, especially after federal legislation (Title IX) dictated that female sports be adequately supported. The nation’s premiere female traveling (“barnstorming”) team was the All American Red Heads. Founded by C. M. “Ole” Olson of Cassville, Missouri, in 1936 and lasting until 1986, the team was coached by Jack R. Moore of Caraway (Craighead County) in its later years. One early star was Hazel Walker, who in 1949 founded her own professional team, the Arkansas Travelers.

Other Sports

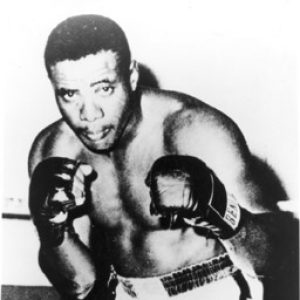

Boxing was transformed from a vicious and bloody affair into a matter of skill following the introduction of new rules in 1865 by the Marquis of Queensbury. A projected bout between James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett and Bob Fitzsimmons planned for Hot Springs in violation of state law was stopped in 1895 by state authorities. Not until 1927 was boxing legalized. Even motion pictures of boxing matches were banned, in part because of the success of Black boxer Jack Johnson. The ban also extended to wrestling.

While wrestling could be found in some public schools and colleges as a competitive sport, professional wrestling flourished in Arkansas after 1930 as a parable of good and evil, to the enjoyment of vociferous fans. Arkansan Tim Scoggins promoted body-slamming for Christ, and female wrestlers were popular as well.

A number of middle-class sports appeared late in the nineteenth century. Croquet remained home-based, but golf helped fuel the creation of country clubs. By the 1920s, golf had become both a spectator sport and one important tool in advancing in the world of business. Another country-club sport was tennis. Public schools and colleges added these sports, but Black athletes were excluded when matches were held at private clubs.

Country people often pitched horseshoes, and contests remain common in rural areas. Bowling had ancient origins, and Logan County sported the “Nine Pins Club,” which began organized play in 1890. Modern equipment, leagues, and expensive tournaments followed in the twentieth century. Softball, a variant of baseball, was played on high school campuses and in slow-pitch adult leagues. Both softball and baseball after 1980 gained new popularity in the public schools, and girls’ softball became an important sport by 2005. Rugby even gained a few adherents late in the twentieth century, but polo had limited appeal even in the nineteenth century. Boat racing on the Arkansas River was also popular in late-nineteenth-century Little Rock.

By far the most important sporting events in rural areas were rodeos, often held during county fairs. Perhaps the most defining cultural event in Fort Smith was the Arkansas-Oklahoma Rodeo and Livestock Show, started in 1933. This became an important part of the state fair in Little Rock, and Thomas Harry Barton, founder of the Arkansas Livestock Show Association, took over the state fair and helped finance the coliseum that bears his name.

This building housed the short-lived Arkansas GlacierCats hockey team from 1998 to 1999. It had local competition from the Arkansas RiverBlades, a team that first tried to call itself the RazorBlades but fell afoul of the University of Arkansas’s domain name of Razorbacks. They then tried “the greatest show on ice” but came too close to the Arkansas Travelers’ “greatest show on dirt.” The GlacierCats and RiverBlades were gone by 2000.

The RiverBlades played at Arkansas’s most advanced indoor sports area, Alltel Arena. Opened in 1999 in North Little Rock, and replete with luxury boxes, the site hosts basketball games, concerts, tractor pulls, and other events. In 2009 the name was changed to Verizon Arena due to a corporate merger; ten years later, it became Simmons Bank Arena.

Roller derby, a national that has experienced several cycles of growth and decline, began increasing in popularity in Arkansas in the mid-2000s.

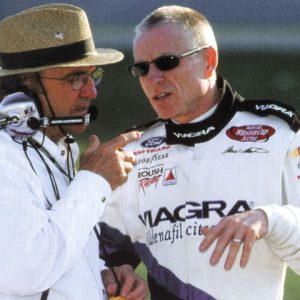

In the twentieth century as Arkansans turned their attention from animals to machines, stock car racing rose to the fore. The national body, NASCAR, was organized in 1948. Arkansas has seventeen dirt tracks and four dragstrips, and thousands of fans attend races each year.

The Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame, founded in 1958, collects and presents information on the sporting careers of notable Arkansas athletes.

For additional information:

Arkansas Sports Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. http://collections.oldstatehouse.com/collections/17467/arkansas-sports-collection;jsessionid=A801BFA6EFFCE6A40E8C4E95FDC051AD/objects (accessed February 11, 2026).

Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. https://www.arksportshalloffame.com/ (accessed February 11, 2026).

Bailey, Jim. Travelers Baseball, 90 Years. Little Rock: Arkansas Travelers Baseball Club, 1997.

Ball, Larry D. “Redeemed, Regenerated, and Disenthralled: Arkansas Resists the Pugilists.” The Record 18 (1977): 15–25.

Butler, Macy V. Unrecognized: Arkansas’ Forgotten Track Legends. N.p.: Antwon Pub. Co., 2025.

Demirel, Evin. African-American Athletes in Arkansas: Muhammad Ali’s Tour, Black Razorbacks, and Other Forgotten Stories. N.p.: 2017.

———. “Baseball’s Vanishing Act.” Arkansas Life, June 2012, pp. 50–53.

Frei, Terry. Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming: Texas vs. Arkansas in Dixie’s Last Stand. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002.

Havres, Jeffrey. “The Life and Times of the Arkansas Diamonds.” Faulkner Facts and Fiddlings 30 (Spring/Summer 1988): 9–14.

Henry, Orville, and Jim Bailey. The Razorbacks: A Story of Arkansas Football. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

House, Archie F. “Boat Racing was City’s Most Popular Sport.” Pulaski County Historical Review 32 (Spring 1984): 17–20.

Huddleston, Duane. “Early Horse Racing in Little Rock.” Pulaski County Historical Review 20 (June 1972): 13–19.

———. “In Days of Old When Knights Were Bold.” Independence County Chronicle 16 (January 1975): 35–45.

Jennings, Jay. Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City. New York: Rodale, 2010.

Kinney, Vela. “Nine Pins Club.” Wagon Wheels, III (Spring 1983): 26–27.

Moffatt, Walter. “Cultural and Recreational Activities in Pioneer Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 13 (Winter 1954): 372–386.

Pike, Ashtyn. “A New Era in College Athletics: Is Arkansas the Best State to Play In?” University of Arkansas Law Review 46 (Summer 2024): 559–589.

Rogers, R. K. “Early History of the Arkansas-Oklahoma Rodeo and Livestock Show, 1934-April 1, 1975.” Fort Smith Historical Society Journal 18 (September 1993): 2–13.

Stancel, Elijah W. “The Growth of Football on the Collegiate Campus: The University of Arkansas, 1892–1912: A Case Study.” Master’s thesis, Arkansas State University, 2002.

Sutton, Keith B. Fishing Arkansas: A Year Round Guide to Angling Adventure in the Natural State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Yeager, Jim. Backroads and Ballplayers: A Collection of Stories about Famous (and Not So Famous) Professional Baseball Players from Rural Arkansas. N.p.: 2018.

———. Hard Times and Hardbacll: A Collection of Stories about the Leagues, Teams, and Players from a Time When Baseball Was Arkansas’ Game. N.p.: 2023.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.