calsfoundation@cals.org

Science and Technology

Arkansas has had a rather conflicted relationship with science and technology throughout its history. On the one hand, the state existed for a long time on the American frontier, separated from the intellectual and academic centers of the rest of the nation; hence, its residents have been popularly perceived throughout history as possessing an anti-intellectual strain, an image on occasion reified during, for example, controversies regarding the place of evolutionary theory in public education. On the other hand, political leaders, and the people themselves, fairly readily support scientific research that promises to have an immediate economic benefit for the state of Arkansas. Given Arkansas’s place as a largely agricultural state, it is no surprise that much of this research has been carried out in the name of creating more durable strains of cotton or increasing rice yields. However, the state has been home to a number of research institutions and has produced scientists and technologists who have had a major influence upon a variety of fields.

Prehistoric Science and Technology

What is now Arkansas may have been one of a handful of centers in the world where plant domestication was carried out independently, the peoples living here not receiving it from other cultures. Worldwide, this transition, often dubbed the “Neolithic Revolution,” occurred between 5,000 and 11,000 years ago and marks the emergence of food production economies. Some studies identify the Ozark wild gourd as the progenitor of common domesticated varieties of squash such as the crookneck, acorn, and scallop. This squash was widespread in North America by at least 8,000 years ago, and archaeological sites in the Ozark Mountains provide clear evidence for domestication that entailed the control and manipulation of plants, primarily to achieve a larger fruit size. In addition to domesticating the Ozark wild gourd, prehistoric peoples also made ready use of domesticated plants that were developed elsewhere, such as maize, which came to Arkansas via what is now Mexico.

Sites such as the Toltec Mounds Site in Lonoke County, which was occupied between AD 650 and 1050, exhibit the extent to which prehistoric peoples of what is now Arkansas possessed knowledge of astronomy. Likely a primary religious center for people who lived throughout the countryside, the Toltec Mounds Site features several mounds that are arranged precisely to line up with the sun on the horizon, at both sunrise and sunset, during the equinoxes and solstices of the year. Such inquiry into astronomical phenomena may have had practical implications for agricultural work as well as ritualistic purposes.

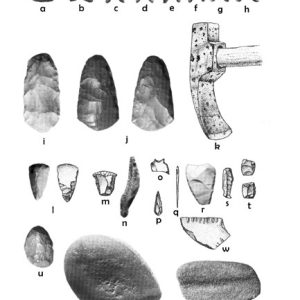

It will likely remain unknown whether any particular technological developments were achieved in the area that became Arkansas. Early Paleoindians probably used hunting tools such as a spear thrower called the atlatl and possessed a fiber technology that allowed them to produce clothing, nets, and other goods. By the Dalton Period, Native Americans in Arkansas were using chipped-stone drills as well as the Dalton point, a spear point that was also used for domestic purposes. The later “food revolution” of plant domestication resulted in the development of pottery for cooking and storing food. Bow-and-arrow technology became widespread in the first millennium AD, though it did not immediately displace other weapons but rather was used alongside them for some time. Archaeologists Michael S. Nassaney and Kendra Pyle speculate that warfare with neighboring peoples may be responsible for the adoption of the bow and arrow by the Plum Bayou culture. Another technological innovation present in prehistoric Arkansas was salt making, usually carried out by boiling brine. Salt making was later practiced by European and American settlers.

Agricultural Research

Before the state began financing scientific research through its universities or elsewhere, such research was often carried out by individuals. In the 1880s, Joseph Bachman, an immigrant from Switzerland, settled in the town of Altus (Franklin County), where previous Swiss and German immigrants had established their homes. The area became the center of the state’s emerging wine industry, given that the environment was ideal for the cultivation of grapes, and Bachman soon began creating new varieties through cross pollination. He won a number of awards during his career, and many of his varieties, such as the Stark Star, remain in use commercially today. Modern research into grape cultivation and winemaking in Arkansas is carried out largely through the University of Arkansas (UA) Enology and Viticulture Research Program, led by Dr. Justin Morris.

In 1888, the state of Arkansas began promoting agricultural research by establishing the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station (AAES) at UA in Fayetteville (Washington County). The original staff consisted of the director and seven others, who were provided with facilities that could most charitably be described as meager. However, as agricultural research promised to provide actual dividends, support for the AAES grew; as of 2009, it covers five research and extension centers across the state, as well as six research stations covering livestock, forestry, fruits, vegetables, and more. Research conducted by the AAES is often shared with farmers and others with vested interests through the University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service (UACES).

The most lucrative cash crop in the state throughout the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century was cotton, and given cotton’s place in Arkansas’s economy, state and private institutions had a real interest in cotton research. Probably the biggest name in state cotton research was Carl Avriette Moosberg, who, from 1948 to 1972, was associated with UA’s Cotton Branch Station in Marianna (Lee County). Moosberg and his colleagues developed a strain they dubbed “Rex,” which was an early maturing variety that proved resistant to leaf blight and easily harvested by machine.

Federal agencies, too, have carried out agricultural research in Arkansas. In 1931, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) started conducting research on rice at a site in Stuttgart (Arkansas County). In 1998, the USDA constructed the state-of-the-art Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center in order to expand its research activities in the state. These include research into rice genetics, physiology, pathology, agronomy, and cereal chemistry to improve the plant’s resistance to disease, environmental stresses, and pests, as well as to increase rice yield and improve grain quality. Many of the researchers at the center have been internationally recognized for their achievements.

The USDA also operates four experimental forests in Arkansas to carry out scientific research on forest ecology and silviculture. The first one in Arkansas—and one of the first experimental forests in the American South—was the Crossett Experimental Forest (CEF), established in 1934 in Ashley County, which was then a center of the timber industry in southern Arkansas. The CEF was created to help landowners develop sustainable forestry plans and manage second-growth forests on cutover lands. Also in 1934, the Sylamore Experimental Forest (SEF) was created in the Ozark National Forest largely to study the use of oak stands as wildlife habitat. In 1948, the Henry R. Koen Experimental Forest (KEF) was established on the south bank of the Buffalo River in the Ozark National Forest for the purposes of researching upland hardwood-dominated ecosystems. Later that decade, the Alum Creek Experimental Forest (ACEF) was created to study the relationship between timber management practices and hydrology. In addition to the USDA, the School of Forest Resources at the University of Arkansas at Monticello (UAM) collaborates with the AAES and the UACES to conduct forestry research under the auspices of the Arkansas Forest Resources Center.

Medical Research

Agricultural research is not the only scientific endeavor that has been conducted in Arkansas, however. Beginning in 1916, the United States Public Health Service and the International Health Commission, successor to the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease, carried out a series of projects in southeast Arkansas for the control of malaria, a disease common to much of Arkansas, given that it was spread by mosquito. This work entailed the cleaning of old ditches and the digging of new ones, as well as the application of oil to areas of standing water so as to eliminate the mosquito’s natural breeding ground. In addition, galvanized screens were added to the homes of people in the project area, and carriers were treated with quinine. Overall, the projects demonstrated the general affordability of malaria-control efforts, though state and local governments ultimately failed to follow through and thus let a potentially important public health initiative founder.

State institutions have also played an important role in medical research. In 1984, doctors Kent Westbrook and James Y. Suen at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) were authorized by the chancellor to begin planning for a cancer institute, known then as the Arkansas Cancer Research Center (later renamed the Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute). Since the center’s establishment, UAMS has become a national leader in cancer research and treatment. In addition, UAMS has also opened the Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, the world’s first center exclusively devoted to researching and treating multiple myeloma, a rare form of cancer that affects bone marrow.

Another health-related research center is the Arkansas Biosciences Institute (ABI), which conducts agricultural and biomedical research with an eye toward advancing the health of Arkansans. The ABI consists of five member institutions: Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Arkansas State University (ASU), the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, the University of Arkansas, and UAMS. The ABI primarily focuses upon such research subjects as genetic engineering that has potential agricultural and medical benefits, tobacco-related research aimed at the treatment and prevention of tobacco-related diseases, and studies of cancer and congenital or hereditary conditions. Some of this research has been spun off into entrepreneurial ventures.

Geosciences Research

Research into the geology and geologic resources of the state began somewhat tentatively in 1857 with the establishment of the Geological Survey of Arkansas, headed by David Dale Owen. However, Owen’s death in 1860, combined with the start of the Civil War the following year, cut short such formal scientific inquiry. Not until 1887 did the state reestablish the Geological Survey of Arkansas, though primarily to investigate (and, it was hoped, confirm) claims regarding the abundance of precious metals in the state. Headed by John Casper Branner, the survey disconfirmed most such claims, though Branner did discover bauxite in a Saline County mineral sample, a discovery that later turned the central Arkansas county into a major mining area. Branner’s survey published fourteen volumes that considerably advanced the understanding of the state’s geology.

In 1893, funding for the Geological Survey of Arkansas was terminated. Not until 1923 was the agency resurrected, this time under George Branner, son of the previous state geologist. However, the agency was underfunded and not able to accomplish much until after World War II. In 1963, the agency became the Arkansas Geological Commission, though its name was later changed to the Arkansas Geological Survey (AGS). The AGS has published geologic maps of the state, as well as documents on Arkansas’s mineral and water resources and fossils, and it continues to serve as the state’s main research organization on the subject of geology. Much of its research can be seen as relating to economic development, especially in tracking fossil fuel and mineral deposits for potential exploitation.

Aside from the AGS, the state’s universities also conduct research into the geosciences. For instance, UA’s Department of Geosciences oversees the Arkansas Surface Water Mapping Program, which conducts studies on sedimentation and water quality on lakes within and outside of the state, as well as producing bathymetric and high-resolution maps of specific reservoirs. In addition, the state’s placement along the New Madrid Seismic Zone has led to a great deal of research, both by state institutions and others, in the field of seismology.

Other Research Areas

The variety of research carried out by state institutions covers an array of scientific fields, though one of the more pertinent, given Arkansas’s advertisement of itself as “The Natural State,” is in the field of biology. Zoologist and anthropologist Samuel Claudius Dellinger, who established the University of Arkansas Museum, expanded that university’s fossil collection (and also resisted the ban on teaching the theory of evolution in the classroom). The AGS and other universities also carry out research on prehistoric life in Arkansas through an examination of the state’s fossil record. The discovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker, long thought extinct, in eastern Arkansas in 2004 sparked a renewed scientific interest in the state’s natural heritage, and scientists from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology conducted repeated surveys of the area in which the bird was spotted, looking for further evidence of the survival of the species. The research of herpetologist Stanley Trauth at Arkansas State University (ASU) in Jonesboro (Craighead County) has found a national and international audience, being featured on television programs such as Life in Cold Blood, a documentary hosted by naturalist Sir David Attenborough and produced by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). In addition, the Aquaculture/Fisheries Center at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) carries out fish-related research with the aim of improving the aquaculture sector of the state’s economy.

Research conducted in Arkansas sometimes goes beyond the boundaries of the state—and sometimes even the boundaries of the solar system. In 2008, Marc Seigar, an astrophysics professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR), was awarded, along with three colleagues at UA, a $1.4 million grant from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to study the supermassive black holes that reside at the center of most galaxies. The four scientists, operating together as the Arkansas Galaxy Evolution Survey, have hypothesized a correlation between the mass of these black holes and the pitch angle of the spiral arms of a galaxy, which may give rise to a means of measuring black hole mass.

Technology

Arkansas has historically lagged behind other states in developing or attracting the sort of high-technology industries that are a feature of North Carolina’s “Research Triangle,” where the local universities, and their graduates, have proved attractive to numerous high-tech enterprises. The state did briefly have a chance to develop such high-tech industry in the post–World War II years. In 1948, Wladimir W. Griegorieff established at UA the Institute of Science and Technology in order to create a research-oriented climate that could contribute to the state’s economic development. However, this was dismantled in 1953. Arkansas’s image as a backward state was further entrenched by Governor Orval Faubus two years later during the desegregation crisis at Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County), thus further stifling potential economic development. Too, Arkansans’ apparent lack of interest in education was only further reinforced by the state’s consistent ranking near the bottom in many national surveys of literacy and educational achievement, as well as highly publicized legal wars against teaching the theory of evolution. Because high-tech companies often prefer to locate to areas where well-educated citizens can provide a competent workforce, many eschewed Arkansas in favor of other states.

Despite these handicaps, Arkansas has been the site of some noteworthy technological developments and enterprises. The state’s only automobile manufacturer, the Climber Motor Corporation, was founded in 1919 with the goal of producing cars that could handle the variety of roads then common in the state, from the paved roads of urban areas to the more treacherous, unpaved trails of the state’s hill country. (Exemplifying some of the problems faced by technology-based industries in Arkansas, the company had to look outside the state for skilled laborers.) A parts shortage and a financial recession doomed the company, which went bankrupt in 1924. A later flirtation with automotive manufacture occurred in the 1960s, when Raymond Thornton and Ed Handy of the Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company (Arkla) were asked by the company to design a small car that would get thirty-five miles to the gallon and be easily reparable. The result was the Handywagon, which was manufactured in Malvern (Hot Spring County) and went into use in May 1964. Arkla was interested in manufacturing the wagons on a larger scale, but because Thornton and Handy could not bring the cost of the individual unit down to $1,000 per vehicle, the company scrapped the plans.

The state has also been home to a number of initiatives in the field of aviation. Charlie McDermott of Chicot County patented a flying machine that he exhibited at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876; reportedly, there were a number of similarities between this machine and the one later built by the Wright brothers. The Hot Springs Airship Company was formed in 1908 to manufacture hydrogen-filled dirigibles but soon moved to New York. Arkansas had the most success in aviation technology with the Arkansas Aircraft Company (later Command-Aire), which was founded in Little Rock in 1926 in the former headquarters of the Climber Motor Corporation. Command-Aire Corporation was briefly one of the nation’s leading aircraft manufacturers, and in 1930, one of its planes, the “Little Rocket,” won the 5,541-mile All-America Flying Derby. However, the Depression hurt the company’s sales, and it went out of business in 1931. Though the state no longer has a native aviation company, Lockheed Martin manufactures missiles at its plant in East Camden (Ouachita County), while Little Rock is home to a Dassault-Falcon Jet Corporation facility.

A substantial number of technological innovations have been instituted in Arkansas in order to deal with problems of flooding and river navigation. In the late 1930s, the Memphis District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Marked Tree Siphons, which essentially lifts the flow of the St. Francis River over a levee and deposits it on the other side. These siphons are the only one of their kind in the world and have been called “unique in the annals of engineering.” In Clark County, the Corps constructed DeGray Dam, which featured the first “pump back capable impoundment” in the agency’s history; that is, a smaller reservoir below the main lake can be used to pump water back through the dam in times of drought and used again to generate electricity. However, the Corps’s largest project in the state has been the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, a series of locks and dams stretching along 445 miles of the Arkansas River in order to aid in flood control and river navigation. At the time of its opening, this constituted the Corps’s largest ever civil works project.

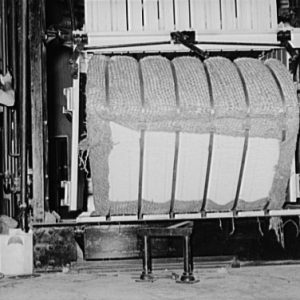

Arkansas has also hosted two respectively unique initiatives in power generation. The first was the Southwest Experimental Fast Oxide Reactor (SEFOR), a nuclear reactor built in Washington County in 1969 by a consortium of private companies. SEFOR was used to test the feasibility of using fast neutrons for fission, a process that allows a reactor to produce more fuel than it consumes. SEFOR was the first reactor to use plutonium rather than uranium for fuel and led to the construction of other breeder reactors around the world. The second initiative was the less influential Mississippi County Community College Solar Power Experiment. In this experiment, the campus of Mississippi County Community College (which later became Arkansas Northeastern College) was constructed in the late 1970s in such a way as to be energy efficient and use both natural light and solar energy. However, the administration of Ronald Reagan cut the funding of alternative energy research in the early 1980s, and the project was left to decay, though some of the data collected during its active phase was later used by other nations that had greater investments in solar power.

The state has been home to a number of different companies in the fields of telecommunications and information technology. Alltel, founded in 1943 as Allied Telephone Company, was a major wireless company before it was purchased by Verizon in 2008. The marketing services company Acxiom began life in Conway (Faulkner County) as Demographics, Inc., in 1969. Information Galore was the first Internet service provider in the state, bringing Internet access to southern Arkansas from its founding in 1994 to its acquisition by Internet Partners of America in 1998.

Arkansas’s universities participate in technological research. The University of Arkansas and the University of Oklahoma jointly operate the Center for Semiconductor Physics in Nanostructures (C-SPIN), with a mission “to develop ways to create and probe structures on the nanometer scale, study their individual and collective dynamics, and explore their use in next generation electronic, optical and chemical systems.”

UALR also maintains a nanotechnology center, a large focus of which is economic development for the state of Arkansas. On May 2, 2012, UALR dedicated its new $15 million nanotechnology center, the UALR Center for Integrative Nanotechnology Sciences. The center will facilitate collaboration among researchers at UALR, UAMS, and UA, as well as with the Food and Drug Administration’s National Center for Toxicological Research in Jefferson (Jefferson County).

Arkansas Scientists and Technologists

Arkansas has been the home state of numerous scientists. Margaret Pittman, a native of Washington County, conducted bacteriological research that aided in developing vaccines for whooping cough (pertussis). William J. Baerg headed up the Department of Entomology at UA and studied venomous arachnids, producing the first account of the effect of a black widow spider bite on humans. Hubert Earle Buchanan, astronomer and mathematician, produced a doctoral dissertation, Periodic Oscillations of Three Finite Masses about the Langrangian Circular Solutions, which further advanced how the fact of stable orbits of heavenly bodies was understood mathematically. Chemist Virginia Ann Rice Williams carried out pioneering studies of rice with the aim of developing more nutritious grains and broke new ground on the scientific study of enzymes in human metabolism. Plant geneticist Florence Clyde Chandler did important work in the breeding of trees from which a quinine derivative could be extracted. Chemist Samuel Proctor Massie Jr. worked on the Manhattan Project and later published a study that led to the development of the breakthrough anti-psychotic Thorazine.

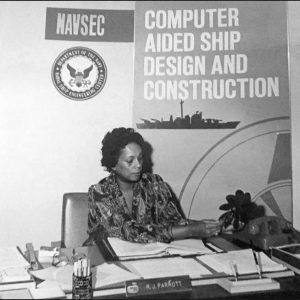

Arkansas has also been home to its share of noteworthy technologists. Charles McDermott of flying machine fame also patented an iron hoe and a cotton-picking machine. However, John Daniel Rust created the first practical mechanical cotton picker and moved to Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) to produce and market his machines. Wallace Henry Coulter, who grew up in McGehee (Desha County), developed the Coulter Principle, which allows for the counting and sizing of microscopic particles suspended in a fluid, and patented a device for counting blood cells. Pine Bluff native Freeman Harrison Owens was a pioneer cinematographer and inventor of cinematic technology, including the A. C. Nielsen Rating System, a plastic lens for Kodak, and the method of adding synchronized sound to film. Engineer Raye Montague was first woman program manager in U.S. naval history and is credited with creating the first rough draft of a U.S. Navy ship using a computer. Inventor Paul Klipsch founded Klipsch Audio Technologies in Hope (Hempstead County), and the company still produces what are recognized as among the world’s best speakers and audio products.

For additional information:

Adams, Mary B., Linda Loughry, and Linda Plaugher, compilers. Experimental Forests and Ranges of the USDA Forest Service. General Technical Report NE-321. Newtown Square, PA: USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station, 2004.

Arkansas Biosciences Institute. https://arbiosciences.org/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

Arkansas Geological Survey. https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center. https://www.ars.usda.gov/southeast-area/stuttgart-ar/dale-bumpers-national-rice-research-center/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

Faulkner, Ed. “The Climber: A Chapter in Arkansas Automotive History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Autumn 1970): 215–225.

Jackson, Kern C. Earthquakes and Earthquake History of Arkansas. Arkansas Geological Commission Information Circular 26. Little Rock: Arkansas Geological Commission, 1979.

Malaria Control: A Report of Demonstration Studies Conducted at Urban and Rural Areas. Public Health Bulletin No. 88. Washington DC: Government Printing office, 1917.

Nassaney, Michael S., and Kendra Pyle. “The Adoption of the Bow and Arrow in Eastern North America: A View from Central Arkansas.” American Antiquity 64 (1999): 243–263.

Rathbun, Mary Yeater. Castle on the Rock, 1881–1985: The History of the Little Rock District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Little Rock: U.S. Army Engineer District, Little Rock, 1990.

Smith, Bruce D. “Eastern North America as an Independent Center of Plant Domestication.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. http://www.pnas.org/content/103/33/12223.full (accessed March 9, 2022).

Smith, William M., Jr. “The Right Plane at the Wrong Time: A Brief History of the Command-Air Aircraft Company.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Autumn 1992): 224–246.

Strausberg, Stephen F. A Century of Research. Fayetteville: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arkansas, 1989.

Trauth, Joy, and Aldemaro Romero. Adventures in the Wild: Tales from Biologists in the Natural State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute. http://cancer.uams.edu/ (accessed March 9, 2022).

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

The Harry K. Dupree–Stuttgart National Aquaculture Research Center was instrumental in conducting aquaculture research that has greatly helped the catfish, baitfish, grass carp, sunshine bass, and other aquaculture ventures in Arkansas.