calsfoundation@cals.org

Dalton Period

The Dalton Period extends from 10,500 to 9,900 radiocarbon years ago (circa 8500 to 7900 BC), during which there existed a culture of ancient Native American hunter-gatherers (referred to as the Dalton people) who made a distinctive set of stone tools that are today found at sites across the middle of the United States. The name “Dalton” was first used in 1948 to refer to a style of chipped stone projectile point/knife. The Dalton point was named after Judge Sidna Poage Dalton, who had found numerous Dalton sites in central Missouri. Evidence of the Dalton culture has been found throughout the Mississippi River Valley. As Dalton points were found in different regions of the mid-continent, they were given different names, such as Holland, Meserve, Greenbrier, Colbert, Hardaway, and Breckenridge. Excavations at the Brand and Sloan sites and surface collections of many other sites in northeast Arkansas provide a wealth of information about the Dalton culture in northeast Arkansas. The internationally famous Sloan site in Greene County is a Dalton Period cemetery and the oldest documented cemetery in the western hemisphere. Studies of stone tools from Arkansas’s Dalton sites have provided many insights into the lives of these hunter-gatherers during the transition from the last ice age to the modern era.

The Dalton Period occurred during the transition from the last ice age to the beginning of the Holocene (Recent) age. By the beginning of the Dalton Period, much of the landscape in Arkansas was covered in trees and grasses, and the sandy braided stream terraces of the Mississippi Delta were dominated by oak and hickory forests. During the Dalton period, sugar maple, hornbeam, beech, and walnut covered the uplands, and ash, bald cypress, and other temperate hardwoods grew along sloughs and terraces in the bottomlands. Dalton people probably had knowledge of a wide range of plant species that were edible or could be used as medicines. Some of the important native plants include persimmon, greenbrier, pokeweed, cattail, amaranth, dock, lamb’s quarters, wild onion, and a wide variety of berries, fruits, and nuts. Based on the density of Dalton artifacts and sites, Arkansas was probably a very rich hunting and fishing ground during the Dalton period: elk, bear, white-tailed deer, raccoon, rabbit, squirrels, and other small mammals were abundant. Although direct evidence is lacking, it is likely that birds, waterfowl, amphibians, reptiles, and fish would have been excellent sources of protein and relatively easy to capture, especially in the Delta region of the Mississippi River Valley.

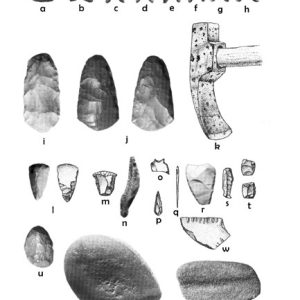

Dalton people continued using most of the stone tool types that their Paleoindian ancestors used: spear points that also served as cutting tools, as well as flake tools (end scrapers, side scrapers, and gravers) usually made from flint and shaped by flaking pieces off a larger core. Several tools that first appear during the Dalton period include the chipped stone drill/awl and adze, the shaft abrader, and edge-abraded cobbles. The most distinctive item in the Dalton stone toolkit, the Dalton point, was used not only to penetrate game like white tailed deer but also to cut and saw meat, hide, wood, and other materials. Dalton points were generally lanceolate (leaf-shaped) in outline. The blade portion of the point was sometimes serrated, similar to the modern bread knife. The bottom, or haft, portion of the Dalton point was made to be concave at the base and tapered so that it would fit into a handle or a spear shaft. As Dalton points were re-sharpened, they began to exhibit an obvious bevel on opposing faces of the blade. This ingenious re-sharpening technique extended the life of the Dalton spear/knife. Archaeologists have documented the specific steps taken in manufacturing and maintaining Dalton spear points and the recycling of Dalton points into other tools, such as burins, end scrapers, and perforators/drills.

The Dalton adze is the earliest known heavy-duty woodworking tool in the archaeological record for North America. Initially referred to as “turtleback scrapers” because of their shape—flat on the bottom and humpbacked on the top—Dalton adzes may have been hafted like modern adzes, in which the cutting blade is perpendicular to the haft or handle. By comparing the wear traces caused by the use of modern replica adzes and wear traces that remain on ancient adzes, researchers have demonstrated that those from the Sloan site were used to chop and cut charred wood. This suggests that Dalton people could have made dugout canoes to travel the local rivers of the middle of the United States. Adzes are also useful for chopping down trees, making grave markers, house posts, wooden containers, as well as scraping and stretching hides. Cobbles of quartzite and other rock types were used as anvils for cracking open nuts, splitting small chert cobbles, and preparing the edges of stone tools. Sandstone was the preferred material for spear shaft abraders. Small exhausted chert cores called pièces esquillés (scaled pieces) were used to peck grooves or circular pockets into less resistant rocks to form such tools as the shaft abrader and anvil. Bone tools are very rarely recovered from Dalton period archaeological deposits. A single-eyed needle made of bone was recovered from Graham Cave in Missouri. Dalton people likely used a wide variety of perishable materials (bone, plant, hide, sinew), but these are very rare finds in most archaeological contexts.

Subsistence technology includes all of the material resources and knowledge involved in gathering and preparing the materials necessary to make clothing, shelter, and food. Dalton subsistence involved a great variety of perishable materials that typically do not survive in the archaeological record. Direct evidence includes food remains associated with artifacts, residues on tools, and isotopic ratios of food types in human skeletal tissue. Indirect evidence includes the shape and size of the tools themselves, residues on the tools, and wear traces on tools from their use. From the stone tools they left behind, it is apparent that Dalton people spent their time hunting and working wood and hides into shelters and clothing, although the actual shelters or clothing have not yet been discovered. To date, there have been no Dalton sites excavated in Arkansas with preserved animal or plant remains, and chemical analyses of skeletal remains from the Sloan site was not possible due to the poorly preserved nature of bone. Deer, nuts, waterfowl, fish, turkey, small mammals (rabbits, squirrels, and raccoon), nuts, berries, and fruits were available in Arkansas and were probably important dietary resources for Dalton Period communities. Although such evidence is lacking in Arkansas, deposits from the Big Eddy site in Missouri and Dust Cave in Alabama suggest that the Dalton diet did include plant foods. Recent evidence from one archaeological site in Missouri suggests that nuts, berries, and possibly even some species of seeds were likely consumed during the Dalton period.

Over 750 Dalton sites have been recorded in northeast Arkansas alone. The few most thoroughly investigated sites in Arkansas include the Brand site in Poinsett County and the Sloan site in Greene County. One model suggests that Dalton people may have concentrated their hunting and gathering activities within circumscribed areas west of Crowley’s Ridge. Dan and Phyllis Morse hypothesize that Dalton settlements include base settlements, food gathering camps, quarries, and cemeteries. They called these circumscribed areas “apparent band territories.” Dalton people probably journeyed to habitats with such resources as stone for making tools; organic materials for clothing, footwear, and containers; and plant resources that furnished essential fats, vitamins, and minerals—all essential for survival. Dalton groups likely planned specific rendezvous to find sexual partners, trade, and communicate skills and accomplishments. The Brand site is a hunting camp where people scraped hides, worked wood into tool handles and other objects, and refurbished their stone toolkits. The Lace site, located in the center of the L’Anguille River basin in Poinsett County, may have been a large base camp. It has been mostly destroyed by modern agricultural practices. The Sloan site, located in the Cache River Basin, was a place that Dalton groups visited to bury their dead, along with tools of their own tool kits or perhaps heirlooms received from relatives. Although other Dalton cemeteries and large base camps probably exist, the majority of recorded Dalton sites appear to be temporary camps set up for gathering and/or processing resources. The stone sources used to make Dalton tools include Crowley’s Ridge chert and many stones from the Ozarks and along the Ozark escarpment. The distribution of stone tools made of different chert types provides clues to the movements of Dalton people.

The Sloan site consisted of a series of tree-covered sand dunes that had been partially cleared and cultivated at the time it was first documented in 1968. Erosion led to the discovery of Dalton artifacts by relic collectors. In 1974, the site was excavated in order to prevent further loss of artifacts and information. Conditions at the site did not preserve human bone. The majority of tiny bone fragments were identified as unquestionably human; none were identified as non-human. The variation in thickness of human skull fragments indicates that both juveniles and adults were buried in the Sloan cemetery. A total of 439 artifacts in small clusters were found during the month-long excavation. The majority of grave goods were Dalton points and adzes. Tools for scraping, engraving or incising, hammering, pecking, polishing and cutting, as well as five small lumps of red ochre and an iron oxide nodule were also recovered. Analysis of the spatial arrangement of human bone fragments and artifact clusters suggests that there were between twenty-eight and thirty graves at the site.

Although the remains of the Dalton period are very limited, we can draw some general conclusions about the culture. Dalton people were the descendants of the Paleoindians based on similarities in technology, settlement, and subsistence strategies, though some of the animals hunted by the Paleoindians—such as the late ice age mammoths and mastodons—were extinct by the time the Dalton culture came into existence. The invention of the chipped stone adze, apparently by a Dalton person, was the first heavy-duty woodworking tool for felling trees and working wood in North America. The Dalton adze laid the foundation for later groups to alter their environment significantly. Based on the distances between stone sources and campsites where stone tools are deposited, Dalton people generally traveled shorter distances than their Paleoindian ancestors and greater distances than their descendents. Although much of their time was spent in their daily tasks of procuring materials for subsistence needs, they clearly devoted time for matters other than food, clothing, and shelter. The planned interment of bodies and grave goods at the Sloan site suggests that Dalton people believed in an afterlife and/or possibly a higher power. If such a belief system was in place by 8500 BC, then it likely that it dates to an even earlier age.

For additional information:

Delcourt, Paul, Hazel Delcourt, and Roger Saucier. “Late Quaternary Vegetation Dynamics in the Central Mississippi Valley.” In Arkansas Archeology: Essays in Honor of Dan and Phyllis Morse, edited by R. C. Mainfort and M. D. Jeter. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Gillam, J. Christopher. “The Paleoindian Period in Northeast Arkansas.” In Arkansas Archeology: Essays in Honor of Dan and Phyllis Morse, edited by R. C. Mainfort and M. D. Jeter. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Goodyear, Albert C. The Brand Site: A Techno-functional Study of a Dalton Site in Northeast Arkansas. Research Series 7. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1974.

Lopinot, Neal H., Jack H. Ray, and Michael D. Conner. The 1999 Excavations at the Big Eddy Site (23CE26) in Southwest Missouri. Special Publication 3. Springfield: Southwest Missouri State Center for Archaeological Research, 2000.

Morse, Dan, F. “The Hawkins Cache: A Significant Dalton Find in Dalton Culture in Northeast Arkansas.” Arkansas Archeologist 12 (1971): 9–20.

———. Sloan: A Paleoindian Dalton Cemetery in Arkansas. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC, 1997.

Morse, Dan F., and Albert C. Goodyear. “The Significance of the Dalton Adze in Northeast Arkansas.” Plains Anthropologist 18 (1973): 316–321.

Morse, Dan F., and Phyllis A. Morse. The Archaeology of the Central Mississippi Valley. New York: Academic Press, 1983.

Walker, Renee B., Kandance R. Detwiler, Scott C. Meeks, and Boyce N. Driskell. “Berries, Bones, and Blades: Reconstructing Late Paleoindian Subsistence Economy at Dust Cave, Alabama.” Midcontinental Journal of Archeology 26 (Fall 2001): 169–197.

Juliet E. Morrow

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Dalton Tools

Dalton Tools  Dalton Period Artifacts

Dalton Period Artifacts  Sloan Site

Sloan Site

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.