calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

In the last years of the 1850s, Arkansas enjoyed an economic boom that was unparalleled in its history. But in the years between 1861 and 1865, the bloody and destructive Civil War destroyed that prosperity. The conflict brought death and destruction to the state on a scale that few could have imagined, and the war and the tumultuous Reconstruction era that followed it left a legacy of bitterness that the passage of many years did little to assuage.

Prelude to War

In the 1850s, Arkansas was a frontier state. Most Arkansans, especially those who lived in the highlands of the north and west (the Ozarks and Ouachitas, respectively), were farmers engaged in subsistence agriculture on small parcels of land. In the fertile lands along the rivers of the state’s southern and eastern lowlands, however, a slavery-based, plantation-style system of agriculture had developed. Cotton was the driving force behind the transformation from subsistence to plantation agriculture in this region. By 1850, Arkansas produced more than twenty-six million pounds of cotton, the majority of it in the Delta region, and the expansion of cotton production seemed certain to continue throughout the next decade.

The growth of slavery in the state was directly linked to this expansion. By 1860, Arkansas was home to more than 110,000 slaves, and one in five white citizens was a slave owner. The majority of these held only a few slaves. Only twelve percent owned twenty or more slaves, the benchmark of “planter” status. But this small group of slave owners, most of whom lived in the southern and eastern lowlands, possessed a disproportionate share of the state’s wealth and political power.

Spurred by the rising price of cotton, the state prospered in the 1850s. Every region of Arkansas benefited from this economic upsurge, but the economic gains in the plantation regions of the southern and eastern lowlands exceeded those in areas where there were few slaves. Throughout the 1850s, the social, economic, and political dissonance between the highlands and the lowlands increased. This dissonance was muted to some extent by the continuing political dominance of the state’s Democratic Party machine known as “The Family.” Many of these political leaders were strong, outspoken supporters of “Southern rights,” but the majority of Arkansans were not. While the majority supported slavery, most Arkansans remained loyal to the Union and continued to hope for a peaceful solution to the slavery question. As the rest of the nation became increasingly polarized over slavery in the 1850s, Arkansans seemed more concerned with the affairs of daily life.

The election of Republican Party candidate Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860, on a platform committed to halting the expansion of slavery, set in motion events that eventually drew Arkansas into the national crisis. Between December 20, 1860, and February 1, 1861, seven Deep South states passed ordinances of secession, declaring that they had severed their bonds with the United States. In February, they formed the Confederate States of America (CSA).

In Arkansas, the reaction to President Lincoln’s election was generally mild, but the state’s voters did vote to hold a convention in March 1861 to consider secession. Despite intense pressure from secessionist elements, including state officials and representatives from the seceded states, a bare majority of the delegates rebuffed every attempt to pass a secession ordinance. The delegates did agree to hold a statewide referendum on the issue on the first Monday in August.

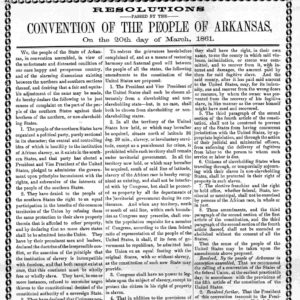

Despite the heated words and animosities that characterized the Secession Convention, many Unionists and secessionists were largely in agreement on one major issue—any attempt to coerce the seceded states back into the Union would be legitimate grounds for Arkansas to secede. Such an action, the delegates declared, would be “resisted by Arkansas to the last extremity.” This was the Achilles heel of the Unionist position, and it put them at the mercy of events over which they had no control. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces in Charleston, South Carolina, opened fire on the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Three days later, President Lincoln called for troops to suppress the rebellion, including 780 men from Arkansas. Arkansas was now forced to choose sides. The Secession Convention reassembled in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on May 6, and the delegates voted overwhelmingly (the final vote was 69–1) for secession. At 4:00 p.m. on May 6, 1861, Arkansas declared that it had severed its bond with the United States. Although pitched as a vote for state’s rights, the convention actually voted on resolutions opposed to state’s rights, specifically the rights of Northern states to limit the spread of slavery in their own territory.

The War in 1861 and 1862

The majority of Arkansans initially supported the decision to secede, but a significant minority opposed the move from the beginning. The most serious challenge to the authority of the new Confederate state government arose in the mountainous regions of the north-central part of the state, where area residents formed a clandestine organization known as the Arkansas Peace Society. Local militias eventually broke up the society, but resistance to Confederate authority continued throughout the course of the war. Despite having the third smallest white population of any Confederate state, Arkansas supplied more troops for the Union army than any other Confederate state except Tennessee.

Outside the northern and northwestern regions of the state, many Arkansans greeted secession with enthusiasm. Historian James Willis has written that no other state had a larger proportion of military-age men fighting for the Confederacy than Arkansas. Many of the young men who rushed to enlist were immediately inducted into the regular Confederate army and sent east of the Mississippi River. Others remained to serve in the state forces.

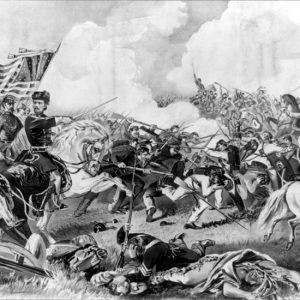

The state remained free of fighting in 1861, but in February 1862, a Union army of 12,000 men led by Brigadier General Samuel Curtis chased a Confederate army out of southwestern Missouri and across the border into Arkansas. The Union army went into camp near Bentonville (Benton County). In early March, Confederate Major General Earl Van Dorn moved north with a well-equipped army of 16,000 men, determined to drive the Federal troops back into Missouri or destroy them. Van Dorn succeeded in getting a part of his army behind Yankees, but his force was strung out for miles, and his men were exhausted from the long march in inclement weather. Curtis was initially caught by surprise, but he quickly regrouped and went on the attack. For two days (March 7 and 8), the armies clashed near a broad plateau called Pea Ridge. By the end of the fighting on the second day, the Union army had scored a decisive victory. Following the battle, Van Dorn moved what remained of his army—along with all available animals, equipment, arms, and ammunition—east of the Mississippi River, leaving Arkansas virtually defenseless.

By May, a Union army moving south from Missouri was threatening Little Rock, and an alarmed Governor Henry Massie Rector hurriedly packed up the state archives and fled to Hot Springs (Garland County). But lengthening supply lines and a determined stand by local militia and Texas cavalrymen in White County forced the Federals to abandon their plans to take the capital. Instead, they marched eastward across the state toward the Mississippi River, liberating slaves and destroying property as they went. In July, they entered Helena (Phillips County) on the Mississippi River without opposition, followed by another unofficial “army” of former slaves. Throughout the remainder of the war, wherever the Federal army went, the institution of slavery crumbled.

The late summer and early fall witnessed changes in both the political and military leadership of Confederate Arkansas. The Secession Convention had reduced the governor’s term from four years to two. A disgruntled Rector announced that he would seek another term, but in the ensuing election, he was defeated by Harris Flanagin, an attorney and former Whig from Clark County who was serving in the Confederate army east of the Mississippi River. On November 14, 1862, Flanagin was inaugurated as Arkansas’s seventh governor, but a lack of money and the presence of Federal troops in the state precluded any significant government action. The major decisions in Arkansas would increasingly devolve on military authorities.

In an attempt to improve deteriorating Confederate military fortunes in the state, the Confederate high command sent Thomas Hindman to Arkansas to take command of what was styled the Military District of the Trans-Mississippi. When Hindman arrived in Little Rock in late May, he was shocked at the situation he found there. “I found here almost nothing,” he remarked. “Nearly everything of value was taken away by General Van Dorn.” To meet the crisis, Hindman employed draconian measures. He declared martial law, established factories, strictly enforced the conscription act, executed deserters, and ordered the immediate burning of all cotton that might be seized by the Federals.

Hindman also authorized the use of “partisan rangers,” bands of guerrillas whose purpose was ostensibly to stage hit-and-run raids on detached Federal units and harass the enemy’s lines of supply. Hindman’s order gave legal sanction to a brutal and merciless guerrilla conflict that historian Daniel Sutherland has called “the real war” in Arkansas. Some of the partisan rangers were legitimate guerrilla fighters, strongly dedicated to defending the state against the Northern invaders, but many were little more than armed bandits whose only causes were self-aggrandizement and the settling of personal grudges. They preyed not only on the Yankees but also on civilians of all political persuasions, contributing greatly to the breakdown of law and order in the state.

Hindman’s harsh actions earned him the enmity of many Confederate sympathizers as well as the Yankees and eventually led to his dismissal as overall commander in the region. But combined with his masterful administrative skills, these actions also managed to create a viable fighting force almost out of thin air. In early December, Hindman moved his new army of 12,000 north from Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to attack an isolated Union division. On December 7, at Prairie Grove, about ten miles southwest of Fayetteville (Washington County), the Confederates clashed not only with that division but also with two additional divisions of Union reinforcements who had moved south from Missouri. In some of the most brutal fighting of the war, each side suffered more than 1,350 casualties. Tactically, the battle was a draw, but during the night of December 7, the Confederates withdrew from the field. The battles at Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove helped secure Missouri for the Union, but much remained to be done before Union forces regained control of Arkansas.

The first full year of war seriously disrupted civil society in the state. “Dozens of county and local governments ceased to function as judges, sheriffs, clerks, and other officeholders fled or failed to carry out their duties,” historian William Shea has noted. “Taxes went uncollected, lawsuits went unheard, and complaints went unanswered. With courts closed and jails open, the thin veneer of civilization quickly eroded. Incidents of murder, torture, rape, theft, and wanton destruction increased dramatically.” In southern Arkansas, many items—such as cotton cards, coffee, tea, and salt—had virtually disappeared. For the next two and a half years, many citizens of the state would experience the horrors of civil war to an extent matched by few other Americans, and the struggle for “states’ rights” and the “Southern way of life” would quickly be overshadowed by the struggle for mere survival.

The War in 1863

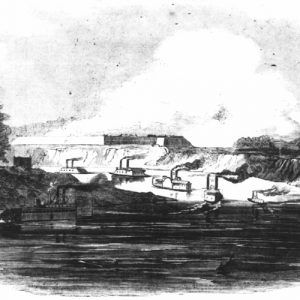

In January 1863, a Union force of more than 50,000 men steamed up the Mississippi River from Vicksburg and overwhelmed the 5,000 Confederate defenders at Arkansas Post, an earthen bastion on the Arkansas River about 120 miles south of Little Rock. Nearly 4,800 Confederate soldiers were taken prisoner, and the Southerners lost vast quantities of sorely needed arms, ammunition, and supplies.

By summer, it had become apparent that only a decisive victory could reverse the Confederates’ sagging fortunes. Major General Theophilus Holmes, the new supreme Confederate commander in Arkansas, devised a plan for just such a victory. His forces would attack and seize Helena, a busy agricultural and commercial center that had been occupied by Union forces the previous July. The attack, begun in the early morning hours of July 4, was an utter failure. The Confederates suffered more than 1,600 casualties and failed to take the city. The disaster was compounded by the news that Confederate General Robert E. Lee had been repulsed at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3 and was retreating with heavy casualties. Even more ominous for Arkansas Confederates was the news that the Confederate Mississippi River stronghold at Vicksburg had surrendered on July 4, freeing up thousands of Union soldiers for service in Arkansas. The significance of that defeat soon became apparent.

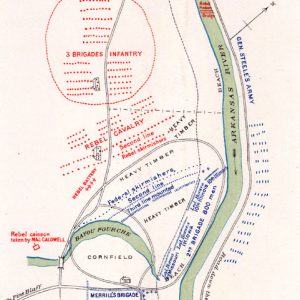

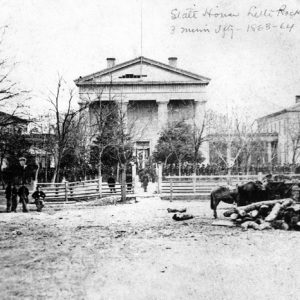

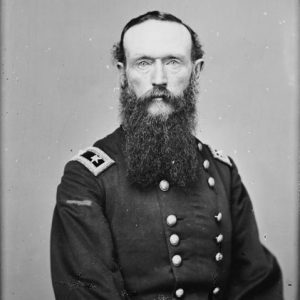

In mid-August, a Union army of 6,000 men under the command of Major General Frederick Steele moved west from Helena toward Little Rock. At Clarendon (Monroe County), they were joined by 6,000 cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John Davidson. By the time this force reached the vicinity of Little Rock, it had been reinforced to about 14,000 men. On September 10, the Union cavalry crossed the Arkansas River south of Little Rock and began to move north toward the city along the south bank of the river, while their infantry moved along the north bank. Furious skirmishing took place south of the river, but the Confederates were forced to evacuate the city in the late afternoon. The rebels also abandoned Fort Smith and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). The state’s Confederate government and the bulk of its military forces withdrew to southwest Arkansas, and the town of Washington (Hempstead County) became the Confederate state capital for the remainder of the war.

In late October, the Confederates tried once again to gain the initiative. Two thousand Confederate cavalry led by Brig. Gen. John Marmaduke moved north from Princeton (Dallas County) to attack Colonel Powell Clayton’s 550-man Union detachment at Pine Bluff. They struck on the morning of October 25, but despite fierce fighting, they were unable to retake the town. The Union garrison was assisted by many former slaves who put up barricades of cotton bales to protect the Federal position.

The Action at Pine Bluff was the last major military action in Arkansas in 1863. During the year, the Union army had secured the Arkansas River from Fort Smith in the west through Little Rock and Pine Bluff to Arkansas Post in the east, and the Mississippi River was securely in its possession. As the Confederate military fortunes declined, discontent with the Confederate government grew. In large areas of Arkansas, food and other necessities were in short supply. Where neither army held sway, the last remnants of civil government and the rule of law disappeared, and guerrilla fighters roamed the countryside.

The War in 1864 and 1865

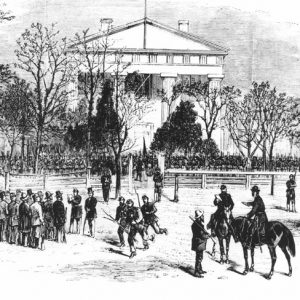

Shortly after the fall of Little Rock, Gen. Steele began to prepare for the establishment of a loyal state government. Under Lincoln’s lenient policy, the state could form a loyalist government whenever the number of people taking an oath of loyalty to the Union reached ten percent of those who had voted in the election of 1860. This was accomplished in January 1864. That same month, Arkansas Unionists drafted a new state constitution. The new document differed little from the original state constitution, with the exception that it outlawed slavery and repudiated secession. The convention also chose a provisional slate of officers, with Isaac Murphy as governor. In March, loyalist voters approved the constitution and the slate of officials by a wide margin, and they elected a new state legislature.

In late March, Union forces embarked on an ambitious military venture known as the Red River Campaign. The Arkansas phase of this operation (which would come to be known as the Camden Expedition) called for a Union army under Steele’s command to move southwest from Little Rock toward Shreveport, Louisiana, where it would meet another Union army moving north from New Orleans, Louisiana. If successful, the operation would destroy the remaining Confederate forces in southern Arkansas and northern Louisiana, reassert Federal authority in Texas, and seize millions of dollars worth of Confederate cotton and other supplies.

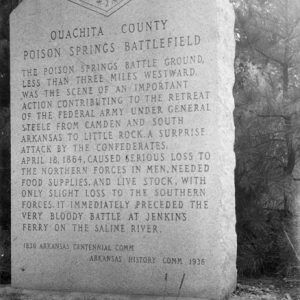

The Red River Campaign turned to disaster for Union forces. The Louisiana wing of the operation was defeated at Mansfield, Louisiana, and forced to retreat. Steele fared little better. Dwindling supplies and growing resistance forced him to abandon his advance on Shreveport. He turned east, and on April 15, his troops occupied the Ouachita River town of Camden (Ouachita County), only recently abandoned by the Confederates. Steele sent a foraging party west with a large wagon train to gather corn and other supplies, but it was ambushed by Confederate cavalry at Poison Spring as it was returning to Camden on April 18. The Confederates overran the wagon train and captured the wagons. The rebels shot wounded Black Union soldiers of the First Kansas Colored Infantry as they lay helpless on the ground and gunned down others as they tried to surrender. Four days later, a second wagon train was ambushed east of Camden at Marks’ Mill.

On April 26, the Union troops evacuated Camden and began a long retreat back to Little Rock. Rebel forces caught up with them as they attempted to cross the Saline River at Jenkins’ Ferry. After a fierce battle, Steele’s army crossed the river to reach the safety of Little Rock on May 3. With the disastrous failure of the Red River Campaign, Confederate forces across the state went on the offensive. In September, Major General Sterling Price launched a raid into Missouri with 12,000 men. After crossing that state from east to west, the rebels were soundly defeated at the Battle of Westport near the Kansas border on October 23 and began a long retreat south. By the time they reached Laynesport (Little River County) in southwestern Arkansas on December 2, only 3,500 men remained.

With the failure of Price’s Missouri raid, major military operations in Arkansas came to an end. Much of the state descended into what one resident called “a state of perfect anarchy” as the last vestiges of law and social stability evaporated. In November, Abraham Lincoln was elected to second term as president, dashing any hope in the South for a negotiated peace. The war in the Military District of the Trans-Mississippi did not officially end until June 2, 1865, but by that time, the Confederacy in Arkansas had long since ceased to exist.

The Civil War was one of the greatest disasters in Arkansas history. More than 10,000 Arkansans—Black and white, Union and Confederate—lost their lives. Thousands of others were wounded. Devastation was widespread, and property losses ran into the millions of dollars. The war left a legacy of bitterness that the passage of many years would not erase.

The Beginning of Reconstruction, 1863 to 1868

The era of Reconstruction was one of the most tumultuous and controversial periods in Arkansas’s history. The process actually began in late 1863, when President Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, often referred to as the Ten Percent Plan. When the president was assassinated on April 14, 1865, the prospects for an easy reunification of the nation were severely dimmed.

In Arkansas, Governor Murphy had worked diligently since his election in early 1864 to promote reconciliation and to prepare the state for its return to the Union. In the elections of 1866, however, a combination of Democrats and former Whigs organized a “Conservative” party that swept away almost the entire Unionist ticket elected in 1864 and returned power to many of the same people who had run the state before the war. Murphy survived only because his term was not up until 1868.

The old planter elites were also engaged in an attempt to restore their prewar economic status. Most had retained control of their land, but with slavery gone, they now had to bargain for the labor of their former slaves. A variety of labor arrangements ensued, but over time, a system called sharecropping emerged as the most popular form. Under this system, a landowner rented a plot of land to an individual to farm independently and furnished everything necessary to grow a crop. The owner would then receive a share of the crop (generally about one half) as rent. The task of supervising these contracts between planters and laborers and of providing food, shelter, education, and justice to the former slaves fell to a federal agency called the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Bureau began operations in Arkansas in June 1865. In the period immediately following the war, Arkansans turned again to cotton as their major money crop. But poor harvests in the two years after the war threatened the economic viability of planters and sharecroppers alike.

Meanwhile, the advent of Congressional or “Radical” Reconstruction in 1867 threatened the political fortunes of the prewar ruling class. The seceded states were divided into five military districts (Arkansas and Mississippi constituted the Fourth Military District), each under the control of a military officer. The states were required to draft new constitutions providing for universal male suffrage and to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Many former Confederates were disqualified from holding office or participating in the process.

In January 1868, seventy delegates assembled in Little Rock to draft the new state constitution. Forty-eight of the delegates could be classified as “Radicals” (sympathetic to Congressional Reconstruction), seventeen as “Conservative” (opposed to Congressional Reconstruction), and five as unaligned. The Radical element was composed of twenty-three Southern white delegates (dubbed “scalawags” by the Conservatives), seventeen white delegates from outside the South (dubbed “carpetbaggers” by the Conservatives), and eight Black delegates. Due largely to their greater unity of purpose, the white delegates from outside the South dominated the convention.

The deliberations were often contentious, but the document that emerged from this convention was, in many ways, a progressive charter. It gave Black males the right to vote; recognized the equality of all persons before the law; forbade depriving any citizen of any right, privilege, or immunity “on account of race, color, or previous servitude;” and established a system of free public education. A popular vote on ratification and the election of new state officials was scheduled for mid-March.

The major issue in the campaign was the granting of full civil and political rights to Black Arkansans. The election was marred by irregularities in voting, but the majority of eligible voters approved the charter. The new state legislature ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and Arkansas was officially readmitted to the Union on June 22, 1868.

Republican Reconstruction and the Militia War, 1868 and 1869

The governor elected under the new state constitution of 1868 was thirty-four-year-old Powell Clayton, a former Federal cavalry officer from Kansas who had served with distinction at the battles of Helena and Pine Bluff. Clayton had been a Democrat before the war, but the growing hostility and violence directed against African Americans and Unionists in the immediate postwar period had caused him to turn against his former party. By 1867, he was active in the creation of the Republican Party in Arkansas. Unlike his conciliatory predecessor, Clayton viewed Reconstruction as little more than a continuation of the war (which in many ways it was), and he employed many of the same aggressive tactics he had used in that conflict. He also used the governor’s vastly expanded appointive powers and the Republican-dominated state legislature to build a loyal base of supporters throughout the state.

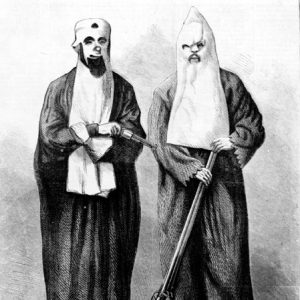

The ratification of the 1868 constitution and the election of Clayton and other Republicans to positions of power in the state was a devastating setback for Arkansas Democrats. Angered by the disfranchisement provisions of the new charter and frustrated by Republican control of the election machinery, many became convinced that their only hope for regaining control of the state government was through the use of extralegal means. Even as voters were going to the polls in March 1868, an organization was beginning to appear in Arkansas that would serve as a vehicle for the Democrats’ attempt to regain control of the state government—the Ku Klux Klan.

Originally founded as a secret fraternal organization in Tennessee in the spring of 1866, the Klan soon became a paramilitary organization that employed terrorist tactics to intimidate or kill African Americans, Republicans, and other Unionists throughout the South. In Arkansas, the rise of the Klan coincided with the beginning of a massive campaign of terror and violence in all but the northwestern counties of the state in 1868. In August, Clayton began to organize the state militia. He rejected numerous requests for troops from voter registration officials around the state, but when the violence continued unabated, he declared that conditions made voter registration impossible in twelve counties, making it impossible to conduct a legal election.

Despite the violence and intimidation, Clayton managed to ensure that the state’s electoral votes went to the Republican candidate for president in the national election in early November. The day after that election, he declared martial law in ten counties and later extended the proclamation to include four additional counties. The state was divided into four military districts (although little attention was paid to the northwestern part of the state, where Klan activity was minimal), and the militiamen were ordered to assemble at designated points.

Over the next five months, the Klan and militia forces clashed in the southwestern, southeastern, and northeastern regions of the state, with both sides accusing the other of harming innocent civilians. The governor agreed to lift martial law for a county only when he was satisfied that law and order had been restored there. Crittenden County was the last in the state to see martial law lifted. When civilian control was finally restored there on March 21, 1869, it marked the official end of what came to be called the Militia War. Historian Allen Trelease has argued that Clayton “accomplished more than any other Southern governor in suppressing the Ku Klux conspiracy.” But the governor’s actions also left a legacy of bitterness with many white Arkansans that severely undermined his attempts to build support for his party and its program in Arkansas.

Republican Schism and the End of Reconstruction, 1869 to 1874

With some degree of order restored, Republican leaders tried to implement measures to bolster and diversify the state’s economy. The plan enjoyed some significant successes, including the establishment of a system of free public schools, the creation of a public university at Fayetteville, and the construction of more than 650 additional miles of railroad track. The program was barely underway, however, when it was beset by problems of inadequate finances, mismanagement, corruption, and intense political partisanship. That partisanship not only pitted Republicans against Democrats but also divided the Republican Party itself.

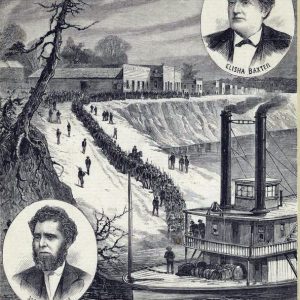

In the spring of 1869, a group calling itself the Liberal Republicans organized in opposition to the Clayton regime. They advocated an end to corruption, greater economy in government, the curtailing of the governor’s powers, and an immediate end to all restrictions on voting rights for former Confederates. Even after Clayton moved to the U.S. Senate in 1871, the infighting continued. In 1872, the Liberal Republicans nominated Joseph Brooks to run for governor. Brooks was an ordained Methodist minister from Ohio who had served in Arkansas as the chaplain of the Fifty-sixth U.S. Colored Infantry during the war. The Regular (pro-Clayton) Republicans responded by nominating Elisha Baxter, a former state legislator from Batesville (Independence County) whose wartime service included the command of a mounted Federal infantry regiment.

The election was marred by massive fraud, but the Regular Republicans controlled the election machinery, and Baxter was declared the winner. The Brooks forces refused to give in. On April 15, 1874, they persuaded a Pulaski County circuit judge to reopen a complaint that Brooks had filed ten months previously and to declare Brooks the legal governor. Armed Brooks supporters then forced Baxter to vacate the governor’s office. Over the next few days, both sides organized militias, and the so-called “Brooks-Baxter War” began. Little Rock became an armed camp, and fighting between rival factions took place at New Gascony (downriver from Pine Bluff) and on the Arkansas River near Palarm (near the present-day Faulkner-Pulaski county line). Finally on May 15, President Ulysses Grant intervened, declaring his support for Baxter and ordering the Brooks forces to disband.

The following month, in the first statewide election since the end of restrictions on former Confederates, voters overwhelmingly approved the calling of a convention to write yet another new state constitution, and they elected Democrats to more than seventy of the ninety-one delegate positions. The document produced by this convention strictly curtailed the governor’s power and limited the state’s power of taxation. In October, voters overwhelmingly ratified the new charter, elected Democrat Augustus Garland governor, and returned the state legislature to Democratic control by huge majorities in both houses. Reconstruction in Arkansas was effectively over.

The war, emancipation, and Reconstruction had been truly revolutionary experiences for the state and the region. But the return to power of the antebellum leaders ensured that Reconstruction was, in the words of Mississippi planter James Alcorn, a “harnessed revolution.” Economic prosperity remained an elusive goal for most of the state’s citizens, and the Black population of Arkansas and throughout the South had to wait for a “second Reconstruction” in the 1950s and 1960s to attain the full civil, political, and educational rights that the first Reconstruction failed to achieve.

For additional information:

Atkinson, J. H., ed. “Clayton and Catterson Rob Columbia County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 21 (Summer 1962): 153–158.

Bailey, Anna, and Daniel Sutherland, eds. Civil War Arkansas: Beyond Battles and Leaders. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Baxter, William. Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove: Scenes and Incidents of the War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Bears, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkin’s Ferry. Little Rock: Eagle Press, 1990.

Blevins, Brooks. “Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War That Refused to End.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 175–207.

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Buxton, Virginia. “Clayton’s Militia in Sevier and Howard Counties.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Winter 1961): 344–350.

Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010.

Christ, Mark, ed. Competing Memories: The Legacy of Arkansas’s Civil War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2016.

———. A Confused and Confusing Affair: Arkansas and Reconstruction. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

———. The Die is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

———. “The Earth Reeled and Trees Trembled”: Civil War Arkansas, 1863–1864. Little Rock: Old State House Museum, 2007.

———. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas of Press, 1994.

———.“This Day We Marched Again”: A Union Soldier’s Account of War in Arkansas and the Trans-Mississippi. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2014.

Christ, Mark K., and Patrick G. Williams, eds. I Do Wish This Cruel War Was Over: First-Person Accounts of Civil War Arkansas from the Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Civil War Sesquicentennial Issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Summer 2011).

Clayton, Powell. The Aftermath of the Civil War in Arkansas. New York: Neale Publishing, 1915. Online at https://www.loc.gov/item/15004463/ (accessed March 6, 2024).

Coffield, Joe E., Jr. “Community Matters: An Empirical Examination into the Causes and Consequences of Factional Allegiance during the American Civil War.” PhD diss., University of Utah, 2012.

Community Conflict: The Impact of the Civil War in the Ozarks. https://ozarkscivilwar.org/ (accessed July 7, 2023).

Cutrer, Thomas W. Theater of a Separate War: The Civil War West of the Mississippi, 1861–1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Dougan, Michael B. Confederate Arkansas: The People and Politics of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

Feistman, Eugene G. “Radical Disfranchisement in Arkansas, 1867–1868.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Summer 1953): 126–168.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Foote, Lorien, and Earl J. Hess, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Gigantino, James J. II, ed. Slavery and Secession in Arkansas: A Documentary History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Goodrich, Carter. “Public Aid to Railroads in the Reconstruction South.” Political Science Quarterly 71 (September 1956): 407–442.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War: A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis: Slawson Printing Company, 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

Huff, Leo H. “Guerrillas, Jayhawkers, and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Summer 1965): 127–148.

Hume, Richard L. “The Arkansas Constitutional Convention of 1868: A Case Study in the Politics of Reconstruction.” Journal of Southern History 39 (May 1973): 183–206.

Kennan, Clara B. “Dr. Thomas Smith, Forgotten Man of Arkansas Education.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 20 (Winter 1961): 303–317.

Kennedy, Thomas C. “Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 207–238.

Leslie, James W. “Hercules King Cannon White: Hero? or Heel?” Jefferson County Historical Quarterly 25 (1997): 4–20.

Matkin-Rawn, Story. “‘The Great Negro State of the Country’: Arkansas’s Reconstruction and the Other Great Migration.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Spring 2013): 1–41.

McNeilly, Donald P. The Old South Frontier: Cotton Plantations and the Formation of Arkansas Society, 1819–1861. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Neal, Diane, and Thomas W. Kremm. The Lion of the South: General Thomas C. Hindman. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1993.

Nordhoff, Charles. The Cotton States in the Spring and Summer of 1875. New York: Burt Franklin, 1876.

Nunn, Walter. “The Constitutional Convention of 1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Autumn 1968): 177–204.

Pearce, Larry Wesley.“The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen in Arkansas, 1863–1878.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 123–144.

———. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1866–1868.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Autumn 1971): 242–259.

———. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1868-1878.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Autumn 1972): 246–261.

Phillips, Samuel R., ed. Torn by War: The Civil War Journal of Mary Adelia Byers. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

Piston, William Garrett, and John C. Rutherford. “We Gave Them Thunder”: Marmaduke’s Raid and the Civil War in Missouri and Arkansas. Springfield: The Ozarks Studies Institute of Missouri State University, 2021.

Richards, Ira D. “The Battle of Poison Spring.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 18 (Winter 1959): 338–349.

———. “The Camden Expedition, March 23–May 3, 1864.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1958.

Roberts, Bobby L. “General T. C. Hindman and the Trans-Mississippi District.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Winter 1973): 297–311.

———. “Thomas C. Hindman, Jr.: Secessionist and Confederate General.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1972.

Rodrigue, John C. Freedom’s Crescent: The Civil War and the Destruction of Slavery in the Lower Mississippi Valley. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Rosen, Hannah. Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Rothrock, Thomas. “Joseph Carter Corbin and Negro Education in the University of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Winter 1971): 277–314.

Scroggs, Jack. “Arkansas in the Secession Crisis.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Autumn 1953):179–224.

Shea, William L. War in the West: Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1998.

Shea, William L., and Earl J. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Singletary, Otis. Negro Militia and Reconstruction. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1957.

St. Hilaire, Joseph M. “The Negro Delegates in the Arkansas Constitutional Convention of 1868: A Group Profile.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Spring 1974): 38–69.

Stafford, Logan Scott. “Judicial Coup D’Etat: Mandamus, Quo Warranto, and the Original Jurisdiction of the Arkansas Supreme Court.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Journal 20 (Summer 1998): 891–984.

Staples, Thomas. Reconstruction in Arkansas, 1862–1874. New York: Columbia University Press, 1923.

Steele, Phillip, and Steve Cottrell. Civil War in the Ozarks. Gretna, LA: Pelican Press, 1993.

Stith, Matthew W. “’The Deplorable Condition of the Country’: Nature, Society, and War on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier. Civil War History 58 (September 2012): 322–347.

———. “Social War: People, Nature, and Irregular Warfare on the Trans-Mississippi Frontier, 1861–1865.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2010.

Taylor, Orville. Negro Slavery in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Thompson, George H. Arkansas and Reconstruction: The Influence of Geography, Economics, and Personality. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1976.

Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

Weeks, Stephen B. History of Public School Education in Arkansas. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1912.

Willis, James. Arkansas Confederates in the Western Theater. Dayton, OH: Morningside Press, 1998.

Woods, James. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Worley, Ted R. “The Arkansas Peace Society of 1861: A Study in Mountain Unionism.” Journal of Southern History 24 (November 1958): 445–456.

Worley, Ted R., ed. “Major Josiah H. Demby’s History of Catterson’s Militia.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 203–211.

Thomas A. DeBlack

Arkansas Tech University

Civil War Military Event Terminology

Civil War Military Event Terminology Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Women in the Civil War

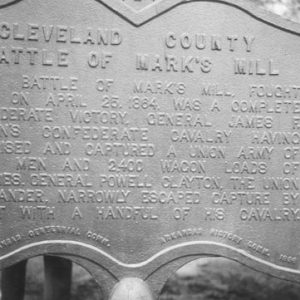

Women in the Civil War Action at Marks' Mills Marker

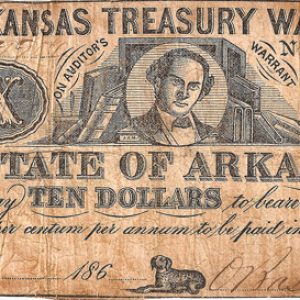

Action at Marks' Mills Marker  Arkansas Civil War Currency

Arkansas Civil War Currency  Battle of Arkansas Post

Battle of Arkansas Post  Battle of Arkansas Post

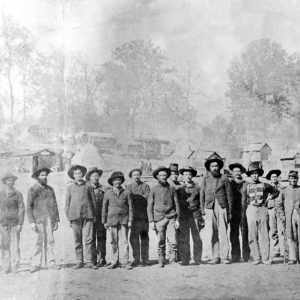

Battle of Arkansas Post  Battle of Arkansas Post Troops

Battle of Arkansas Post Troops  Battle of Palarm

Battle of Palarm  Battle of Pea Ridge

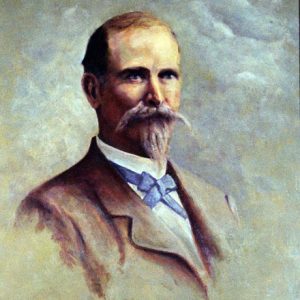

Battle of Pea Ridge  Elisha Baxter

Elisha Baxter  Elisha Baxter's Forces at Pine Bluff

Elisha Baxter's Forces at Pine Bluff  Bayou Fourche

Bayou Fourche  Brooks-Baxter War

Brooks-Baxter War  Joseph Brooks

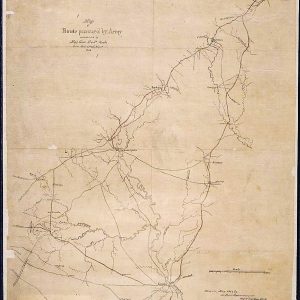

Joseph Brooks  Camden Expedition Map

Camden Expedition Map  Celebrating African American Soldiers

Celebrating African American Soldiers  Civil War Amputation Field Set

Civil War Amputation Field Set  Civil War Bond

Civil War Bond  Civil War Events Map

Civil War Events Map  Powell Clayton

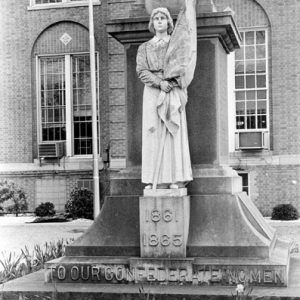

Powell Clayton  Confederate Women Monument

Confederate Women Monument  CSS Arkansas

CSS Arkansas  Samuel Curtis

Samuel Curtis  David O. Dodd

David O. Dodd  Engagement at St. Charles

Engagement at St. Charles  Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery

Fayetteville Confederate Cemetery  First Arkansas Light Artillery Battery

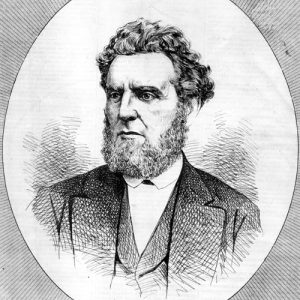

First Arkansas Light Artillery Battery  Harris Flanagin

Harris Flanagin  Fort Curtis

Fort Curtis  Fort Steele School

Fort Steele School  Gunboat Eastport

Gunboat Eastport  Helena Civil War Scene

Helena Civil War Scene  Thomas Hindman

Thomas Hindman  Theophilus Holmes

Theophilus Holmes  Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument

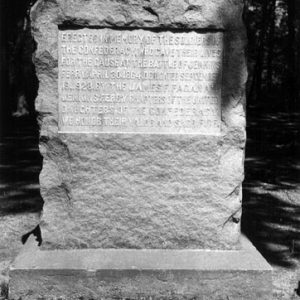

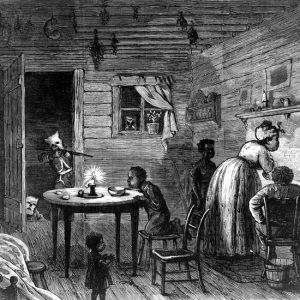

Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry Monument  Ku Klux Klan Attack

Ku Klux Klan Attack  Ku Klux Klansmen

Ku Klux Klansmen  John Marmaduke

John Marmaduke  Military Districts

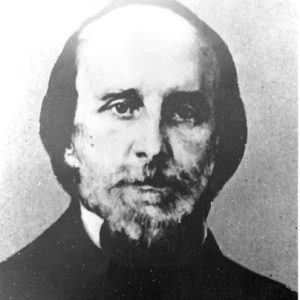

Military Districts  Isaac Murphy

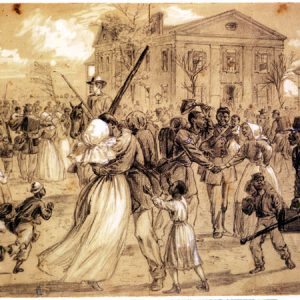

Isaac Murphy  Old State House, Union Occupation

Old State House, Union Occupation  Pea Ridge National Military Park Battlefield

Pea Ridge National Military Park Battlefield  Engagement at Poison Spring Marker

Engagement at Poison Spring Marker  Henry Rector

Henry Rector  Slavery Resolution

Slavery Resolution  Frederick Steele

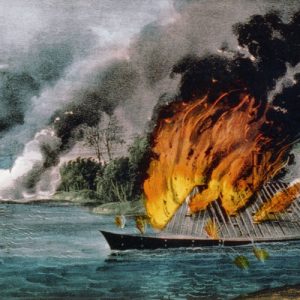

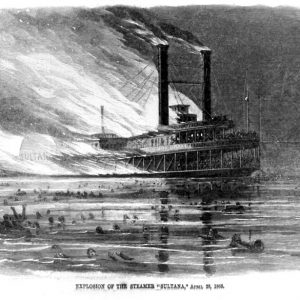

Frederick Steele  Sultana Disaster

Sultana Disaster  "Sultana," Performed by Harmony

"Sultana," Performed by Harmony  Sultana

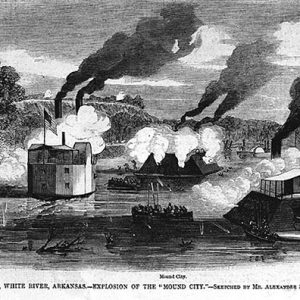

Sultana  USS Mound City

USS Mound City  Victory Parade

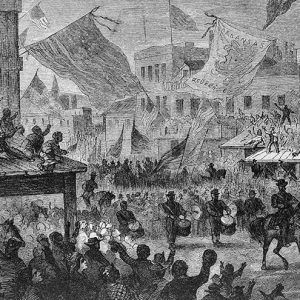

Victory Parade  Omer Rose Weaver

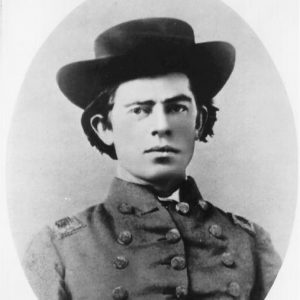

Omer Rose Weaver

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.