calsfoundation@cals.org

Women in the Civil War

In Arkansas, women supported both secession and Unionist movements, worked in war industries, nursed sick and wounded soldiers, and were involved in other innumerable ways on both sides in the conflict. The experiences of women in the state during the war varied widely, but all women in Arkansas at the time were impacted by the Civil War in some way.

Women were involved on both sides of the secession movement in Arkansas. A group of Little Rock (Pulaski County) women gave Captain James Totten an inscribed sword to thank him for his leadership during the Arsenal Crisis in February 1861. Women filled the gallery during the Secession Convention, and Little Rock resident Martha Trapnall tossed Isaac Murphy a bouquet of flowers after he refused to change his vote during the final vote to leave the Union.

Women in the state assisted with the mobilization of Confederate military units early in the war. As units organized, women provided temporary uniforms and other goods necessary to outfit an army entering the field. Most notably, many early units from Arkansas received flags made by local women. The Hempstead Rifles, a company that served in the Third Regiment of Arkansas State Troops at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, received a First National variant from Bettie Conway. Another company in the same regiment, the Pike Guards of Washington County, received a flag presented by Mary Willis Stirman. Most of these flags were made by female family members of soldiers in these respective units, although a few were constructed by members of the community or even women in a nearby town without any direct connection to the men in a particular regiment.

In Southern states, women’s efforts to create necessary supplies and clothing to outfit their soldiers early in the war allowed the Confederacy to field an army more easily, as it did not have an effective logistical system. As the Confederate government was unable to supply their troops with clothing effectively early in the war, it implemented the commutation system by which states supplied uniforms to their troops. In Arkansas, uniforms and other materials were produced at the state penitentiary, while women at home continued to make smaller items. The mayor of Little Rock, William Ashley, offered a gold medal to the person who wove the greatest amount of woolen cloth, while Little Rock’s Arkansas True Democrat offered a medal for second place. Women across the state competed for the prizes, with entries received from Freeo (Ouachita County), Sulphur Springs (either the Pope County or Columbia County community), and Mount Elba (Cleveland County). Nancy Anderson of Ouachita County won the competition with eighty-one yards of jeans and twenty-four yards of checked linsey.

By early 1862, many white men from across the state were in Confederate service, leaving their families led by women on the home front. After the Battle of Pea Ridge on March 7–8, 1862, the Federal Army of the Southwest under the command of Brigadier General Samuel Curtis moved across the northern portion of the state in an effort to capture Little Rock. Arriving in Batesville (Independence County), some of the German-speaking Federal troops frightened the women in the town. This early occupation was viewed differently by both sides, with professions of fear on the part of the Arkansans and Curtis claiming that his troops were welcomed with open arms.

Work in war industries by women proved to be an important part of the Confederate effort. With the utilization of both women and children to make cloth and uniforms, as well as ammunition and other goods, men were freed from these positions and could enter active military service. Arkadelphia (Clark County) became a major manufacturing center for the Confederate army, with factories making cloth, weapons and ammunition, and salt, with women holding numerous positions in these efforts. Women from across the state heeded the call published in the True Democrat in December 1862 to grow herbs, including marsh rosemary and common dandelion, to be used in medical supplies.

The experience of enslaved women in Arkansas during the Civil War was very different than that of white women. With more than 111,000 enslaved persons in the state in 1860, roughly half were female. About forty-six percent lived on large plantations that included at least twenty-five slaves, and forty-three percent lived on smaller-scale farms with between five and twenty-four enslaved people. The remaining eleven percent lived in towns or on small farms with fewer than five total enslaved people.

Life early in the war did not change much, but when Union forces entered the state in early 1862, some enslaved people took the opportunity to flee to Federal lines in an effort to gain their freedom. Thousands fled to the relative safety of “contraband camps” in Helena (Phillips County), where they lived in squalor with little support, at least at first. Many died from diseases that swept through the city. African Americans continued to flee to the relative safety of Union strongholds during the course of the war, with Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Little Rock, and DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) each offering escaped enslaved people a safe haven in refugee camps. For the enslaved people who remained with their owners, their lives changed due to shortages, increased workloads, the threat of impressment by civil and military authorities, and the ever-present likelihood that their owners could move them to Texas to try to keep them out of the hands of Union troops.

While adult enslaved men who escaped to the safety of Helena or other cities often enlisted in the Union army or served as laborers on the fortifications surrounding the city, many enslaved women were forced to support their families through other means. Martha Thompson, for example, arrived in the city in February 1864 and worked as a woodcutter providing fuel for Union gunboats in an effort to provide for her baby, as her husband served in the army and her brother worked for the military. Many formerly enslaved women worked on military farm colonies in the Delta late in the war, established to take some of the strain off the Union army to supply these freed people. In October 1863, the War Department instituted an official program to put freed people to work, paying men thirty dollars a month and ten a month for women. The women worked in roles including cooks, servants for officers, laundry workers, and common laborers.

Unionist women in Arkansas experienced many of the same trials as their Confederacy-supporting neighbors. Struggling to provide for their families while bands of guerrillas and Confederate forces roamed the countryside, these women often served as the head of their household while the husbands and fathers served Federal military units. Later in the war, a number of military farm colonies were established in northwestern Arkansas. Families lived together and relied upon one another for mutual defense while farming tracts of land.

Many women and their families on both sides were forced to flee their homes and ultimately the state during the war. The experience of being unable to provide for their children and reliably grow crops that would not be confiscated by military forces on both sides led women to leave their homes and travel to the relative safety afforded by nearby cities. Confederate women led their families into southern Arkansas, including to cities such as Camden (Ouachita County) and the Confederate capital of Washington (Hempstead County). Shortages late in the war forced the Confederate army in Arkansas to disperse widely to allow for the gathering of food for both men and animals, and many families left the state for Texas or Louisiana to better obtain provisions.

Federal women took refuge in Union-controlled strongholds such as Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Fayetteville (Washington County), and Little Rock. Others left the state for Missouri or other northern states. The women and their families who fled enjoyed some protection from Confederate forces and guerrillas that roamed the countryside while also accessing somewhat better food sources.

Many documented cases of women serving in Confederate and Union military units have been discovered by modern researchers, although few or none appear to have served in Arkansas. A female soldier served in the 116th Illinois Infantry in late 1862 and early 1863 but was discovered prior to the Battle of Arkansas Post and so likely never made it to the state. Few other accounts of women serving in military units in or from Arkansas exist.

The strange case of Loreta Velazquez appeared in print more than a decade after the conclusion of the war. Velazquez claimed to have impersonated a Confederate officer named Lieutenant Harry T. Buford, raising more than 200 men for a military unit. She later claimed that this occurred at Hulbert (Crittenden County), but other known inaccuracies in her book leave doubts about the authenticity of her claims. She later claimed to have served as soldier and spy in both the eastern and western theaters of war.

Emily Weaver, a Batesville resident, was arrested in St. Louis, Missouri, on suspicion of being a spy for Confederate forces. Charged on the word of her cellmate, Weaver eventually escaped Federal custody. The charge was eventually dropped even after Weaver escaped, leading to a conclusion of her case.

Women served as nurses in hospitals in Little Rock, Helena, and other cities throughout the state, as well as in the field with units on active campaign. Mary Whitney Phelps accompanied her husband’s Missouri regiment in the field when it fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge, serving as a nurse during and after the engagement. Other women cared for soldiers in the immediate aftermath of battles in homes, churches, and other public buildings. After the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry, hospitals operated at Tulip (Dallas County), Princeton (Dallas County), Camden, and Magnolia (Colombia County). The Dallas County hospitals utilized homes near the battlefield, staffed by both military medical personnel and volunteer female nurses from the local community.

With the conclusion of the war in 1865, many women continued to lead their familial units, as thousands of Arkansas troops lost their lives in the war and never returned home. Formerly enslaved women worked to establish lives as free people while also searching for long lost relatives. The efforts to rebuild the state in the aftermath of the war continued into the Reconstruction period.

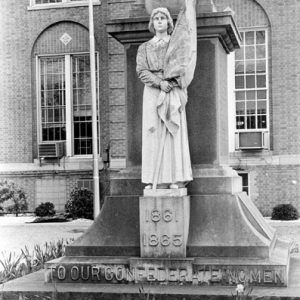

Much of the postwar interpretation of the origins and causes of the conflict were shaped by women, including in Arkansas. The United Daughters of the Confederacy led efforts to place monuments across the state honoring Confederate soldiers and worked to tailor the interpretation of the war taught in public schools, helping to fashion what is now known as the Lost Cause Myth of the Confederacy.

For additional information:

Bradbury, John F., Jr. “‘Buckwheat Cake Philanthropy’: Refugees and the Union Army in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Autumn 1998): 233–254.

Bunch, Clea. “Confederate Women of Arkansas Face ‘the Fiends in Human Shape.’” Military History of the West 27 (Autumn 1997): 173–187.

Confederate Women of Arkansas in the Civil War: Memorial Reminiscences. Fayetteville: M&M Press, 1993.

Davis, William C. Inventing Loreta Velasquez: Confederate Soldier Impersonator, Media Celebrity, and Con Artist. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016.

Dedmondt, Glenn. The Flags of Civil War Arkansas. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2009.

Eno, Clara B. “Activities of the Women of Arkansas During the War Between the States.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 3 (Spring 1944): 5–27.

Frank, Lisa Tendrich. “Domesticity Goes Public: Southern Women and the Secession Crisis.” In The Die is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861 edited by Mark Christ. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

Hall, Richard. Women on the Civil War Battlefront. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Hess, Earl J. “Confiscation and the Northern War Effort: The Army of the Southwest at Helena.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1985): 56–75.

Howard, Rebecca A. “No Country for Old Men: Patriarchs, Slaves, and Guerrilla War in Northwest Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 75 (Winter 2016): 336–354.

James, Nola A. “The Civil War Years in Independence County.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 28, no. 3 (1969): 234–274.

Jones, Kelly Houston. “Women after the War: Profiles of Change and Continuity.” In Competing Memories: The Legacy of Arkansas’s Civil War, edited by Mark Christ. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2016.

Jones, Shanna. “Civil War Women of Fort Smith: Laying the Foundation for Social Justice and Progressive Era Reform Movements.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 48 (September 2024): 17–24.

Lovett, Bobby L. “African Americans, Civil War, and Aftermath in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Autumn 1995): 304–358.

Moneyhon, Carl H. “The Slave Family in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Spring 1999): 24–44.

Moneyhon, Carl H., and Virginia Davis Gray. “Life in Confederate Arkansas: The Diary of Virginia Davis Gray, 1863–1865, Part I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Spring 1983): 47–85.

———. “Life in Confederate Arkansas: The Diary of Virginia Davis Gray, 1863–1866, Part II.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Summer 1983): 134–169.

Shea, William L. “A Semi-Savage State: The Image of Arkansas in the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Winter 1989): 309–328.

Sutherland, Daniel E. “Guerrillas: The Real War in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 523 (Autumn 1993): 257–285.

Wilson, Arabella Lanktree, and James W. Leslie. “Arabella Lanktree Wilson’s Civil War Letter.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Autumn 1988): 257–272.

David Sesser

Southeastern Louisiana University

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military Confederate Women Monument

Confederate Women Monument  Monument to Confederate Women

Monument to Confederate Women  Loreta Velazquez's Two Looks

Loreta Velazquez's Two Looks  Emily Weaver

Emily Weaver

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.