calsfoundation@cals.org

Batesville (Independence County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º46’11″N 091º38’27″W |

| Elevation: | 360 feet |

| Area: | 11.60 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 11,191 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | December 20, 1848 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

881 |

1,264 |

2,150 |

2,327 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

3,399 |

4,299 |

4,484 |

5,267 |

6,414 |

6,207 |

7,209 |

8,263 |

9,187 |

9,445 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10,248 |

11,191 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Geographically, Batesville was destined to exist. It stands at the point where waters of the White River exit from the sedimentary stone of the Ozarks. River traffic was forced to stop at the shoals to offload cargo, regardless of the direction of travel. Warehouses, supply stores, and buyers of furs and produce naturally congregated there. The town became one of the major cultural centers of the region. In the nineteenth century, its leaders, many of whom moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), exercised influence on the political development of Arkansas far beyond what its modest size promised.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first Euro-American settlers, French fur-traders who were in the valley possibly as early as the mid-eighteenth century, left behind the name of the creek which enters the White from the north—Poke (or Polk) Bayou—but nothing else. The earliest documented settler is John Reed, one of the mercantilists who was living at Poke Bayou by 1812. By 1819, when tourist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft visited the area, there was “a village of a dozen houses” at Poke Bayou. He considered his arrival there from upstream a “return to the land of civilization.”

Schoolcraft’s host was Robert Bean, who had moved into the settlement a year earlier and had begun buying up the preemption deeds of many who lived in the area. In the same year that Schoolcraft passed through, Arkansas Territory was separated from Missouri Territory. In 1820, Independence County was created from Lawrence County, and Bean was able to offer the land of the Poke Bayou settlement for sale as the county seat. The sheriffs of Lawrence and Independence counties and other investors purchased the land and became proprietors of the new county seat; they were to recover their money by the sale of the lots. This experiment in privatizing the establishment of a new town, relieving the new county of a tax burden, was widely approved.

It was named Batesville in honor of James Woodson Bates, territorial delegate who had been pivotal in the establishment of Arkansas Territory. Judge Bates moved to the town, becoming an important early lawyer there. In order to occupy the point where Poke Bayou flowed into the White, Batesville’s original plat of 1821 consisted of an unusual linear pattern of fourteen blocks, with a public square. The town soon had a two-story brick courthouse, a brick jail, and several other brick buildings, all in the lower blocks of the plat, an area subject to flooding that caused relocation up Main Street to higher ground throughout the nineteenth century.

With a federal land office for the region and settlers pouring into the White River country, the new town prospered as Davidsonville, county seat for Lawrence, diminished. Among the new arrivals were entrepreneurs from the eastern states, and many of them were active Whigs during the antebellum decades. After the west bank of the White became open to settlement when the Cherokee returned the land to the government in 1828, and after steamboat transportation on the upper White began in 1831, Batesville became the major river port of the southeastern Ozarks. The town was surrounded by good farmland, and many of the plantation owners lived in the town.

John Ringgold and other leading businessmen of the town served in the territorial and state general assemblies. The new state constitution was carried to Washington DC by Batesville lawyer Charles Fenton Mercer Noland, who became nationally famous as the author of the “Pete Whetstone” letters. Batesville had one of the branches of the State Bank of Arkansas, housed in an impressive neoclassical building constructed in 1838 on Main Street. Unfortunately, the State Bank failed because of massive default on unsecured loans. The building survived until the 1880s as an office building and hotel.

In 1841, Dr. Phillip P. Burton accused Dr. Trent C. Aikin of medical malpractice, kicking off a feud between the Batesville doctors and their families that lasted years. By 1849, when the feud ended, Aikin’s reputation had been destroyed, one doctor had lost a son and the other his life. Despite the feud, Batesville remained a regional center for the health professions. William M. Lawrence, who practiced medicine in Batesville from 1848 until his passing in 1892, was appointed the state surgeon general in 1881.

Although itinerant preachers and house-gatherings were known from early years, the first church building was the Methodist church in 1838, followed by the Presbyterian in 1842, the Baptist in 1847, and the Episcopalian in 1866.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

When the Civil War began, Batesville was a prosperous mercantile and cultural center for northeastern Arkansas, but when the war was over, the town was destitute, and it took decades for recovery. Even so, Arkansas College and many fine homes were built in the 1870s. The Batesville Daily Guard began publishing in 1877 and continues to serve residents today. Because of its strategic location, Batesville was the headquarters for successive military forces in the region—three Confederate and two Union occupations, punctuated by periods of isolation. Civil War events in Batesville include skirmishes in 1862 and 1863, as well as an expedition in 1864. Reconstruction in Batesville saw the building of a Freedmen’s Bureau school and some Ku Klux Klan resistance. Elisha Baxter, a Batesville resident and Union officer during the war, became the state’s tenth governor, though he was soon ousted and had to fight to regain his governorship in the conflict known as the Brooks-Baxter War.

Arkansas College (now Lyon College), founded in 1872 by the Presbyterian Church after the town failed to receive the new state university, steadily produced graduates, many of whom settled locally and strengthened the cultural and economic base in the area. Today, Lyon is a highly ranked small liberal arts college with international faculty and student body. Also located in the city is the University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville (UACCB).

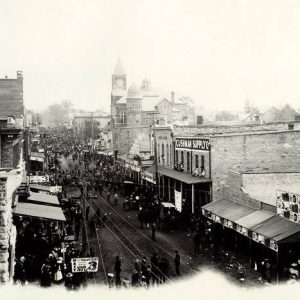

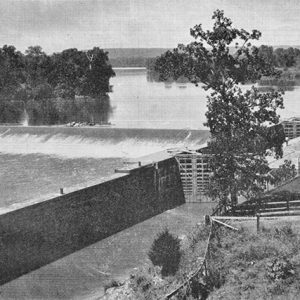

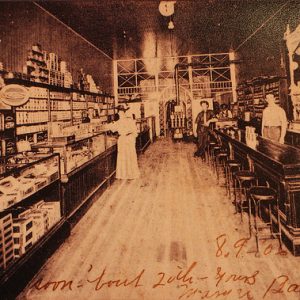

The late nineteenth century brought from the surrounding county new settlers who desired town life. The growth resulted in the construction of many new businesses and banking buildings in the downtown section, some of which still stand. Batesville became a center for steamboats, many of which were owned and operated by local people. River traffic flourished until it was slowed by the building of the first three of ten projected locks and dams, then replaced in the opening decades of the twentieth century by railroads. The St. Louis, Iron Mountain, and Southern Railroad first arrived in 1883 and was extended up the White River valley in 1905.

Early Twentieth Century

A disastrous fire in 1920 destroyed forty houses and other structures in the downtown area, but the courthouse survived with its documents intact. A bridge across the White River replaced the ferries in 1928, making traffic to the south easier. The rise of the poultry industry and the addition of many small diversified industries, such as the International Shoe factory, began to balance Batesville’s traditional focus on agriculture and trade.

Modern Era

KBTA, Batesville’s first radio station, aired its debut broadcast in 1950.

In recent decades, larger companies moved to the area, such as Arkansas Eastman (chemicals) and the Independence County Steam Plant (electricity), and their needs were supported by the creation of an expanded commercial airport in 1970. The Batesville Historic Residential District, centered on Main Street, with the guidance of the Batesville Preservation Association, displays many blocks of historic homes that survived the 1920 fire. The Main Street Project works to preserve the original downtown business district, although much of the commercial activity of the town has moved to the south and west, following the population growth. With the addition of many subdivisions to the original town and the growth of nearby villages, the town has become a mercantile center for a large area. The population is primarily white; the African-American segment has been a small percentage (less than five percent) of the population, from slavery to the present day, and the Vietnamese and Hispanic additions of the late twentieth century were small. By the 2010 census, however, Hispanics made up about thirteen percent of the population.

Notable Figures

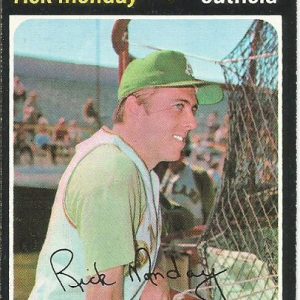

Figures of note who have called this area home include: Judge Hubert Fairchild, alleged spy Emily Weaver, businessman Simon Adler, minister J. L. Brown, calligrapher Raymond DaBoll, Rear Admiral Morgan Powell, Professor John Wolf, author Catherine Sweazey Barker, race-car driver Mark Martin, baseball player Rick Monday, newspaper publisher and state senator Oscar Eve Jones, Justice Paul Ward, and educator Asbury Mansfield Miller, and Attorneys General Thomas Johnson and Leslie Rutledge.

Attractions

Attractions include the Garrott House (built in 1842) and the Cook-Morrow House (built in 1909), both listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Old Independence Regional Museum has been open since 1998. Batesville is also home to the ruins of the Ruddell Mill and the Batesville Confederate Monument.

For additional information:

Barnett Sr., Mrs. I. N. “Early Days of Batesville.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 11 (Spring 1952): 15–24.

Lankford, George E. “Town-Making in the Southeastern Ozarks.” Independence County Chronicle 31 (October 1989–January 1990): 1–19.

McGinnis, A. C. “Batesville, Historic Town of a Historic County.” Independence County Chronicle 8 (July 1967): 35–47.

Official Website for the City of Batesville, Arkansas. https://www.cityofbatesville.com/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

Old Independence Regional Museum. Batesville, Arkansas.

Oliver, Janet. “Black in Batesville: Stories from My Family.” Independence County Chronicle 62 (January 2021): 2–53.

Phillips, Samuel R., ed. Torn by War: The Civil War Journal of Mary Adelia Byers. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013.

Powell, Admiral Morgan A. “Journal of a Batesville Visitor.” Independence County Chronicle 6 (October 1964): 30–40.

Up from the River: The Story of Batesville’s Historic Main Street. Batesville, AR: Main Street Batesville, 2016.

Worley, Ted R. “Glimpses of an Old Southwestern Town.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 8 (Summer 1949): 133–159.

George E. Lankford

Batesville, Arkansas

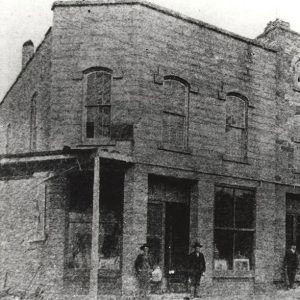

Adler Building

Adler Building  Simon Adler

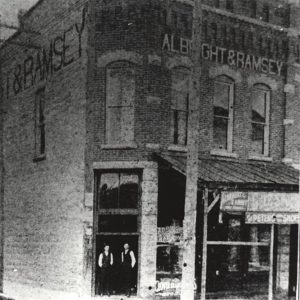

Simon Adler  Albright & Ramsey Store

Albright & Ramsey Store  Arkansas College

Arkansas College  Arkansas National Guard Memorial

Arkansas National Guard Memorial  Arkansas Scottish Festival

Arkansas Scottish Festival  Batesville Dairy Truck and Cheerleaders

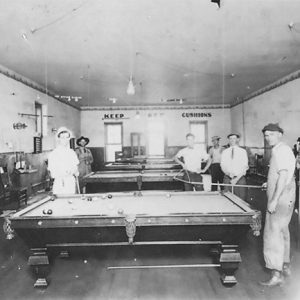

Batesville Dairy Truck and Cheerleaders  Batesville Billiards Hall

Batesville Billiards Hall  Batesville 1915 Flood

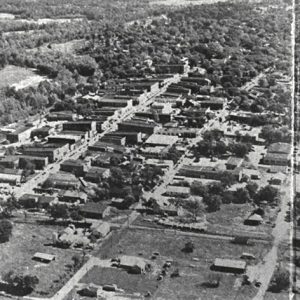

Batesville 1915 Flood  Batesville Aerial View

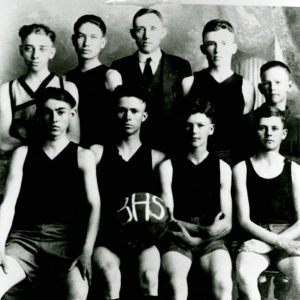

Batesville Aerial View  Batesville Basketball

Batesville Basketball  Batesville Church

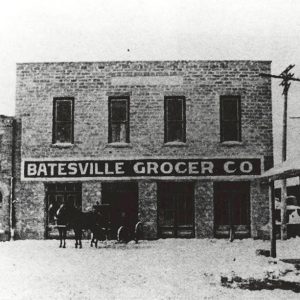

Batesville Church  Batesville Grocer

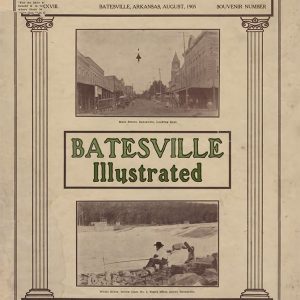

Batesville Grocer  Batesville Guard Magazine

Batesville Guard Magazine  Batesville High School

Batesville High School  Batesville Lime Mill

Batesville Lime Mill  Batesville Limestone

Batesville Limestone  Batesville Saloon

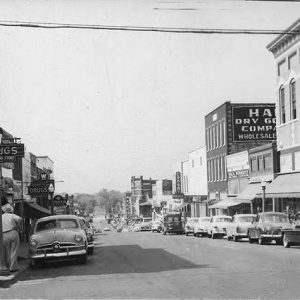

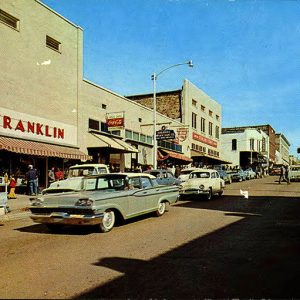

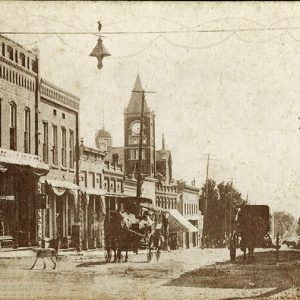

Batesville Saloon  Batesville Street Scene

Batesville Street Scene  Batesville Street Scene

Batesville Street Scene  Batesville Street Scene

Batesville Street Scene  Batesville Street Scene

Batesville Street Scene  Batesville Street Scene

Batesville Street Scene  Batesville Street Scene

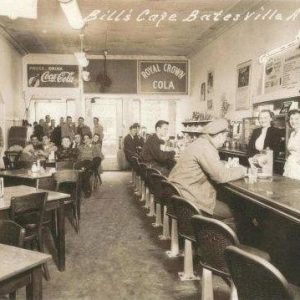

Batesville Street Scene  Bill's Cafe

Bill's Cafe  Cook-Morrow House

Cook-Morrow House  Dowdy Building

Dowdy Building  Earnheart Cafe in Batesville

Earnheart Cafe in Batesville  Garrott House

Garrott House  Independence County Courthouse

Independence County Courthouse  Independence County Map

Independence County Map  KBTA's "Uncle Bill" Smith

KBTA's "Uncle Bill" Smith  Lock and Dam Number 1

Lock and Dam Number 1  Lock and Dam Number 1

Lock and Dam Number 1  Love Hollow Quarry

Love Hollow Quarry  Aaron Lyon

Aaron Lyon  Mark Martin Museum

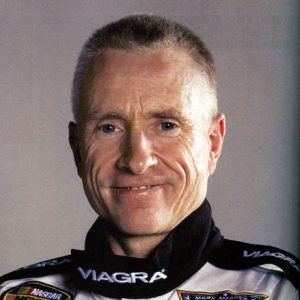

Mark Martin Museum  Mark Martin

Mark Martin  Masonic Orphans Home

Masonic Orphans Home  Maxfield Store

Maxfield Store  Miller Creek Bridge

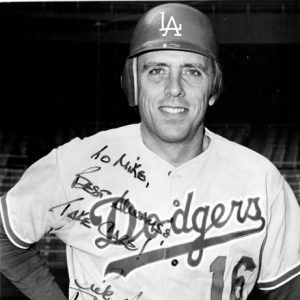

Miller Creek Bridge  Rick Monday

Rick Monday  Rick Monday

Rick Monday  John P. Morrow Confectionery

John P. Morrow Confectionery  Old Independence Regional Museum

Old Independence Regional Museum  Polk Bayou Bridge

Polk Bayou Bridge  Ramsey's Ferry

Ramsey's Ferry  Ringgold House

Ringgold House  Southerland Stores

Southerland Stores  Wheel Store

Wheel Store  White River Fishing

White River Fishing  White River Scene

White River Scene

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.