calsfoundation@cals.org

Hospitals (Civil War)

A wide range of Civil War hospitals in Arkansas included field hospitals established in the immediate aftermath of battle, commandeered houses and churches, and somewhat permanent post hospitals in occupied areas. Union bases tended to have more purpose-built hospital facilities, while Confederate doctors made use of any available buildings, such as colleges, hotels, churches, and private homes.

The need for hospital facilities became obvious soon after Arkansas seceded from the Union and the new Confederate recruits became ill from the myriad diseases that afflicted their camps. Hospitals were established wherever large groups of troops gathered, often treating soldiers from specific regiments or from the same states. In early 1862, for instance, Confederate forces in Washington County established the Mount Comfort Hospital and Ozark Hospital near Mount Comfort and the Fayetteville Hospital in Fayetteville, each of which were regimental in nature.

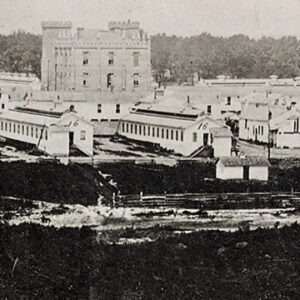

The buildup of troops in central Arkansas led Confederate officials to establish the only general hospital—a hospital not associated with a specific military unit—in Arkansas at St. Johns’ College in Little Rock (Pulaski County), along with the Rock Hotel Hospital in the center of the city. By early 1862, the three-story brick building at St. Johns’ was overwhelmed by sick troops, with the Confederates setting up at least twenty satellite facilities. The Confederates had built a pair of two-story wooden additions at St. Johns’ by the time Union troops captured Little Rock in September 1863 and left some 1,400 sick troops behind for the Federals to care for. Union troops took over the facility, and by the war’s end they had constructed eleven additional single-story wards at St. Johns’. They would occupy the campus until the spring of 1867.

The first major battle in Arkansas, fought at Pea Ridge (Benton County) on March 7 and 8, 1862, revealed the difficulties that would face both armies in the sparsely settled Arkansas wilderness. Field hospitals were established at the log huts and frame buildings in the immediate vicinity of the battlefield as the poorly supplied surgeons did what they could for the desperately wounded soldiers, pitching tents to shelter the hundreds of wounded who could not fit in the available structures. The Federal wounded who could be moved were later taken to hospital facilities in Missouri. Confederate casualties were moved to the Arkansas River Valley, with many being taken to Little Rock. They would soon be joined by hundreds of wounded Confederates from the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee in April 1862, after which many of the largest buildings in Little Rock were outfitted as hospitals, including the Presbyterian and Episcopal churches at 8th and Scott streets and a row of businesses on Main Street.

After being treated in nearby homes and a church following the December 7, 1862, Battle of Prairie Grove, Confederate casualties were taken to a hospital in Cane Hill (Washington County), most likely in the Cane Hill College building. The hospital remained there until March 1863, when Union officials ordered it closed; its patients were moved to Fort Smith (Sebastian County) following accusations that the hospital was being used as a base for Rebel spies. The Federal wounded were eventually taken to Fayetteville, where two churches, the Masonic Hall, a seminary, a school room, and three private residences were used as a general hospital. It was closed in May 1863 and the patients moved to Springfield, Missouri. A Union hospital again operated in Fayetteville from November 1863 to November 1864, and post hospitals were established there from August 1865 to May 1866 and from June 1867 to April 1869.

As Union troops gained control of the Arkansas River Valley, they established hospitals at all of their permanent posts. After the Federals seized Helena (Phillips County) in July 1862, a hospital was established in the home of Confederate general Thomas C. Hindman, which was later augmented with other hospital structures. The supply base at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County) became the major medical center for Union troops serving along the lower White River, many of whom suffered from recurring bouts of malaria and from scurvy. Sick and wounded Federals in Little Rock were placed in the St. Johns’ College hospital complex, though those facilities were sometimes bolstered by additional spaces, as when three private homes were procured as hospitals following the 1864 Camden Expedition; the U.S. Arsenal also housed hospital operations. Base hospitals also were established at Fort Smith and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

Union hospitals were segregated, and the facilities allocated to soldiers in the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) were vastly inferior to those used by white soldiers. Medical inspectors reported that, at the USCT hospital in Fort Smith, “the kitchens, out buildings and grounds were filthy in the extreme, and the medical officer in charge did not manifest much efficiency in the discharge of his duties.” In Pine Bluff, “the police of the wards in the hospital for white soldiers was fair but the police of the negro hospital was filthy in the extreme,” and in Helena the black hospital “was the dirtiest place inside and the filthiest place outside it was fallen to my lot to inspect….Not a thing about the whole establishment could I find to mention in favorable terms.” Fatality rates at the USCT hospitals were dramatically higher than at white facilities.

As the war wound down, Confederate forces had major hospitals at Magnolia (Columbia County), Camden (Ouachita County), and Princeton (Dallas County). In December 1864, Union medical officials reported general hospitals at Little Rock with forty-six beds for officers, 580 beds for white soldiers, and 129 beds for black troops; Fort Smith had 325 beds, Helena had 250 beds, and DeValls Bluff had 187 beds.

For additional information:

“Army Hospitals in Fayetteville. 1862–1869.” Flashback 8 (May 1958): 23–24.

“Confederate Dead in Washington County Hospitals.” Flashback 4 (March 1954): 14.

Glatthaar, Joseph K. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: Meridian, 1990.

Kellum, Rachel M. “Surgeons of the Severed Limb: Confederate Military Medicine in Arkansas, 1863–1865.” MA thesis, University of Central Oklahoma, 2014.

“Our Hospitals.” Pulaski County Historical Review 10 (June 1962): 22.

Pierce, Aaron B. “St. John’s [sic] College.” Pulaski County Historical Review 36 (Summer 1998): 39–44.

Pitcock, Cynthia DeHaven. “Gunpowder, Lard and Kerosene: Civil War Medicine in the Trans-Mississippi.” In “The Earth Reeled and Trees Trembled”: Civil War Arkansas, 1863–1864, edited by Mark K. Christ. Little Rock: Old State House Museum, 2007.

Pitcock, Cynthia DeHaven, and Bill J. Gurley, eds. I Acted from Principle: The Civil War Diary of Dr. William M. McPheeters, Confederate Surgeon in the Trans-Mississippi. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Roberts, Bobby, and Carl Moneyhon. Portraits of Conflict: A Photographic History of Arkansas in the Civil War. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Rock Hotel Hospital Materials (BC.MSS.04.21). Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/search/searchterm/mss.04.21 (accessed January 30, 2026).

Shea, William L. “The Aftermath of Prairie Grove: Union Letters from Fayetteville.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Winter 1988): 345–361.

Shea, William L., and Earl J. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Steiner, Paul E. Disease in the Civil War. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1968.

United States Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion. 12 vols. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1870.

Mark K. Christ

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.