calsfoundation@cals.org

Camden Expedition

| Location: | Ouachita County |

| Campaign: | Red River Campaign |

| Dates: | March 23 to May 3, 1864 |

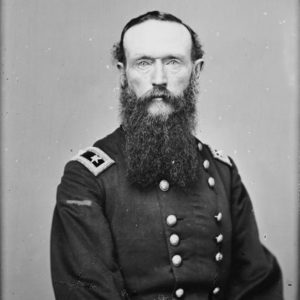

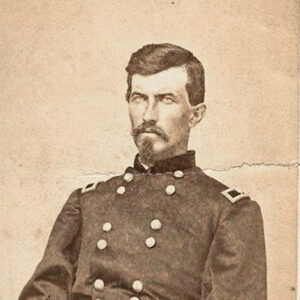

| Principal Commanders: | Brigadier General Frederick Steele (US); Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, Major General Sterling Price (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Steele’s Union Department of Arkansas and VII Army Corps (estimated 13,754) (US); Price’s Confederate District of Arkansas plus Major General John G. Walker’s Division, Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill’s Arkansas Division, and Brigadier General Mosby M. Parson’s Missouri Division (14,000) (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 2,750 (estimated) (US); 2,300 (estimated) (CS) |

| Result: | Confederate victory |

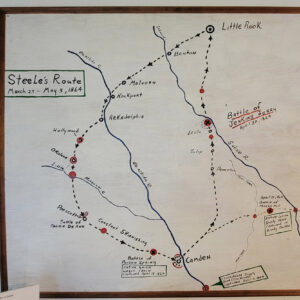

Part of the Red River Campaign, the Camden Expedition resulted from Union brigadier general Frederick Steele’s orders to strike south from Little Rock (Pulaski County) and converge with Major General Nathaniel P. Banks’s column in northwest Louisiana before marching to Texas. Because of poor logistical planning, horrible roads, and strong Confederate resistance, Steele abandoned this plan to occupy Camden (Ouachita County). Losing battles at Poison Spring (Ouachita County) and Marks’ Mills (Cleveland County), Steele became unable to supply his army and retreated toward Little Rock. The Confederates caught Steele while he was crossing the Saline River engaging in the last battle of the campaign at Jenkins’ Ferry (Grant County).

In 1864, the Trans-Mississippi Theater presented several problems for Union general-in-chief Henry Halleck. Confederate forces maintained the capability of offensive operations and tightly held much of the territory. In addition, Emperor Maximilian could possibly threaten the unstable region from Mexico in a bid to reclaim the lost Mexican province of Texas, and any Union operations moved troops into hostile territory away from stable supply lines and fortified positions. To eliminate these problems, Halleck ordered Banks to march from New Orleans, Louisiana, to link with Rear Admiral David Porter’s Mississippi Squadron on the Red River, which transported additional infantry troops. They could then coordinate their movements into northwest Louisiana while Steele pushed south from Little Rock. Once consolidated, the force would capture Shreveport, Louisiana, and thrust into Texas. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, who replaced Halleck as general-in-chief on March 9, 1864, questioned the stratagem but reluctantly allowed it to continue, as troops were already in motion.

In Little Rock, Steele received direct orders to support Banks on March 15. Having argued against support from his position, Steele was not adequately prepared; thus, he placed his command at a disadvantage from the outset. Undaunted, he ordered Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s Frontier Division at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to consolidate with his column in Arkadelphia (Clark County) by April 1. Steele’s army left Little Rock on March 23 with inadequate provisions. Fearing attacks on his column en route to Arkadelphia, he directed Colonel Powell Clayton, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) garrison commander, to distract local Rebels with a sally from Pine Bluff. Dispatching two aggressive junior officers, Clayton’s detachments won a March 30 victory near Mount Elba (Cleveland County), thus allowing Steele’s column to arrive in Arkadelphia unscathed.

Waiting three days in Arkadelphia for Thayer, Steele continued southwest without him on April 1. Using the Military Road to march toward the new state capital at Washington (Hempstead County), Union troops reached the Little Missouri River on April 3. With provisions dwindling, no contact from Thayer, and a growing Confederate force in front, continuing to Shreveport appeared doubtful. Undeterred, Steele determined to march forward searching for a better tactical position and hoping to link with Thayer. Driving the Confederates off the river’s banks at Elkin’s Ferry (Clark and Nevada counties), Steele continued forward, contacting Thayer’s command on April 5.

Halting to consolidate his force, Steele began to realize the gravity of the situation. Since leaving Little Rock, his men had been on half rations, and Thayer’s force further strained the diminishing supplies; furthermore, the Confederate force in front grew. Continuing to Shreveport appeared impossible. Viewing the map, Steele saw an opportunity in Confederate major general Sterling Price’s position. Believing Steele’s objective was the state capital, Price had his men working on a trap at Prairie D’Ane (Nevada County), placing the majority of the Confederates in the region across Steele’s front. On April 10, Steele shoved Price southward at Prairie D’Ane, thus opening the Washington-Camden Road to the east. Thinking the Union troops were falling for the trap, Price did not fully suspect the possibilities of Steele’s directional shift and failed to block the maneuver adequately. Using the Washington-Camden Road, the Union troops rapidly seized the fortified town of Camden with minor resistance on April 15, a site from which Steele believed he could resupply his army and continue south to support Banks.

In Louisiana, Steele’s march south had the desired effects. The Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, supervising the defense of Louisiana under Major General Richard Taylor, could not determine which column constituted the primary attack element. Steele’s progress had continually drawn Smith’s attention, and much to Taylor’s chagrin, Smith considered diverting troops from Taylor’s command to strengthen Price’s defense of Arkansas. While Steele’s movement to Camden may not have realistically threatened northwest Louisiana, it created ample frustration in the Confederate upper command.

Steele found Camden devoid of the supplies needed for his large force. Price, realizing the strength of the Camden fortifications, refused to attack the town directly; instead, his forces harried Federal communication and supply lines. Trying to find rumored sources of corn west of Camden, Steele dispatched a column to acquire it under the command of Colonel James M. Williams. On April 18, Confederate brigadier generals John Sappington Marmaduke and Samuel Bell Maxey surprised the returning Union party at Poison Spring, overwhelming the column and depriving Steele of needed supplies, men, wagons, and livestock. Surprisingly, provisions arrived April 20 from Pine Bluff, convincing Steele that rations could be obtained from that direction. Three days later, he sent a column toward Pine Bluff under the auspices of Lieutenant Colonel Francis Drake. On April 25, Brigadier General James F. Fagan’s Confederate force overran this column at Marks’ Mills. With the loss of manpower and dwindling supplies, Steele slipped out of Camden during the night of April 26, marching toward Little Rock.

Arriving at Jenkins’ Ferry in the Saline River bottoms on April 29, Steele immediately began constructing a pontoon bridge across the swollen river. Marmaduke’s Confederate cavalry engaged Union brigadier general Frederick Salomon’s rearguard on April 29, halting as darkness fell and reengaging the next day at dawn. The situation darkened for Steele as Confederate forces from Louisiana under Smith’s direct command began consolidating with Price’s force on April 30. Sensing the tactical disadvantage of being pressed to the Saline River, the Union rearguard took a strong position, anchoring its flanks against a flooded creek on the right and swampy woodland on the left, leaving little room for the Confederates to maneuver. The Confederates assaulted the Union lines piecemeal, failing to break them. By 12:30 p.m. on April 30, Smith ended the assault, and Steele slipped across the river. Arriving in Little Rock on May 3, Steele’s Camden Expedition was over.

While the Camden Expedition faded into history, the legacies of Poison Spring, Marks’ Mills, and Jenkins’ Ferry remain debated because of racial atrocities at each. Confederates massacred members of the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment at the Engagement at Poison Spring and were accused of killing freedmen at Marks’ Mills. In a reciprocal action, members of the Second Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment bayoneted several surrendering Confederate artillerymen, killed wounded Confederates, and mutilated bodies at the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry. As a result, interpretation of events at the state parks and in literary sources remains disputed.

Taken as a whole, the Camden Expedition was a Union failure. Unable to achieve his objective, Steele abandoned his march south and returned to Little Rock. The Union suffered an estimated 2,750 casualties and the loss of 635 wagons, 2,500 animals, eight artillery pieces, and two steamships. Yet this was not a major Confederate victory. While the Confederates repulsed the Union advance, they failed to destroy Steele’s army in the field. Confederate totals reflect less loss, with 2,300 casualties, thirty-five wagons, fewer than 100 animals, three artillery pieces, and one steamship destroyed.

As a result of the Union failures in Arkansas, combined with Banks’s dismal showing in Louisiana, the Red River Campaign as a whole is considered a Union defeat. Parts of Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas remained firmly in Confederate control, Northern possession of needed cotton supplies remained elusive, and no demonstration of strength existed to deter possible Mexican invasion. Combining the Camden Expedition’s numbers with Banks’s statistics, Union losses during the campaign surpassed 8,100 men, fifty-seven artillery pieces, 822 wagons, nine naval vessels, and a staggering 3,700 mounts during the Red River Campaign. Furthermore, the absence of troops from Eastern and Western theaters prevented Grant from applying stronger pressure on more valuable targets in 1864. For the Confederates, the campaign victory was marginal. While they repelled Union troops, they failed to destroy either Federal column. About 6,500 men were lost, as well as three steam vessels and about 700 mounts. As a result of the perceived victory in Arkansas, Smith would unwisely support Price’s plans for an 1864 invasion of Missouri, which drew upon the manpower of Arkansas and ended in a Confederate disaster.

Several sites related to the expedition constitute the Camden Expedition Sites National Historic Landmark.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission, 1967.

Christ, Mark K. “‘War to the knife’: Union and Confederate Soldiers’ Accounts of the Camden Expedition, 1864.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Winter 2014): 381–413.

Forsyth, Michael J. The Camden Expedition of 1864 and the Opportunity Lost by the Confederacy to Change the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003.

———. The Red River Campaign of 1864 and the Loss by the Confederacy of the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002.

Gill, John P. “Union Retreat from Camden: The So-Called ‘Camden Expedition.’” Pulaski County Historical Review 64 (Spring 2016): 23–28.

Derek Allen Clements

Pocahontas, Arkansas

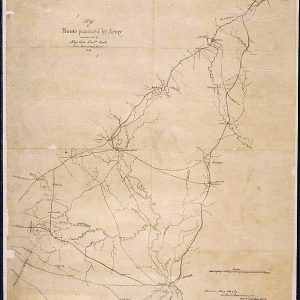

Camden Expedition Map

Camden Expedition Map  Richard Gano

Richard Gano  Jenkins Ferry Entrance

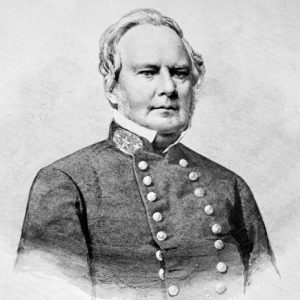

Jenkins Ferry Entrance  Sterling Price

Sterling Price  Richard Taylor

Richard Taylor  Friedrich Salomon

Friedrich Salomon  Frederick Steele

Frederick Steele  Steele's Routes

Steele's Routes  Supplies Destroyed

Supplies Destroyed  James M. Williams

James M. Williams

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.