calsfoundation@cals.org

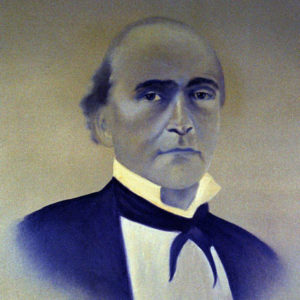

Harris Flanagin (1817–1874)

Seventh Governor (1862–1865)

Harris Flanagin, the seventh governor of Arkansas, had his four-year term cut short when he surrendered Arkansas’s Confederate government following the surrender of the Trans-Mississippi Department at the end of the Civil War. After the fall of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1863, he reconvened the Confederate state government in Washington (Hempstead County), thus becoming Arkansas’s only governor to head a government in exile.

Harris Flanagin was born on November 3, 1817, in Roadstown, New Jersey, to James Flanagin, a cabinetmaker and merchant who had emigrated from Ireland in 1765, and Mary Harris. No records indicate his middle name, and little is known about his early life. Flanagin was educated in a Society of Friends (Quaker) school and became a professor of mathematics at Clermont Seminary in Frankfort, Pennsylvania, at age eighteen. He next opened his own school at Paoli, Indiana, where he also began the study of law.

Armed only with a letter certifying him to be “a gentleman well educated and possessing a good moral character,” Flanagin moved to Arkansas in 1839, settling in Greenville (Clark County) before relocating to Arkadelphia (Clark County), where he established his law office on the town square. His primary interest seems to have been speculating in land with an old Pennsylvania friend, Benjamin Duncan, who served as Clark County sheriff from 1844 to 1846.

A Whig in politics, Flanagin was elected to the fourth Arkansas General Assembly in 1842, serving in the state House of Representatives for one term. Although he volunteered for the Mexican War, his company seems not to have completed its organization. In 1847, he was elected captain of a militia company. In 1848, Flanagin won a spirited contest against Democrat Hawes H. Coleman for the office of state senator in the Sixth General Assembly. Again, he served only the one term. After the collapse of the Whig Party in the 1850s, his political activity was reportedly limited to serving as an Arkadelphia city alderman.

Flanagin married Martha Elizabeth Nash of Hempstead County on July 3, 1851. Flanagin had been raised a Baptist, but after he married, he attended the Presbyterian church with his wife, thus becoming known locally as a “trunk Baptist.”

He re-entered politics in 1861 when he was elected to attend the state Secession Convention. A reluctant secessionist, he was highly regarded by the former Unionists and left the convention after the passage of the ordinance of secession on May 6 in order to accept the captaincy of Company E of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles. He participated in actions at Wilson’s Creek (Oak Hills) and Pea Ridge (Elk Horn Tavern). After the death of Colonel James McIntosh and the reorganization of the regiment, Flanagin was elected colonel.

During the summer of 1862, Flanagin was serving in the Army of Tennessee when his name was put forth as a gubernatorial candidate in a public letter by a strong coalition of ex-Unionists (mostly ex-Whigs) and Democrats who wished to supplant the highly unpopular incumbent, Henry Massie Rector, whose most recent action had been to issue a proclamation threatening to secede from the Confederacy. The Constitution of 1861 had contrived to shorten Rector’s term by scheduling a gubernatorial election for the fall of 1862. During these months, Flanagin kept a small diary but made no reference to his candidacy, thus leading some writers to the erroneous conclusion that he had no knowledge of his nomination at the time of his election. However, private correspondence from Arkansans in the Army of Tennessee reveals that the men were both aware of his nomination and anxious for his success. His friends in Arkansas did all the campaigning for him. A pro-Rector paper tried to stir up anti-Irish sentiment by claiming the challenger’s last name was O’Flanagin, but the colonel outpolled Rector by more than a two-to-one margin.

Sworn in on November 15, 1862, Flanagin called on the legislature for laws to help people cope with shortages of salt, aid impoverished soldiers’ families, and stop profiteering and liquor production. Some laws were passed, but Flanagin took a passive attitude toward executive responsibilities and failed to offer effective leadership. A Baptist minister reported to the governor that he had heard it said, “Your governor loves whiskey too well to get him to stop still houses.” In contrast to many Southern governors, he did not oppose the imposition by Confederate authorities of conscription or endorse an extreme states’ rights position. He worked strongly to get Confederate authorities to take seriously the defense of Arkansas, and he accompanied the army on its futile assault on the Union-held port of Helena (Phillips County) in July 1863. He also made two efforts to raise state troops for defense. After the fall of Arkansas Post in January 1863, he called for volunteers to serve for sixty days. Since the Federals did not follow up their victory, there was no need, and in any case, the state had no weapons with which to arm the men. Then in August, when a Federal column began marching on the capital, Flanagin formed a company of old men, which he led himself. Since the Confederates failed to make a serious effort to defend the capital, the Union army captured Little Rock on September 10,1863. Flanagin and most of the state’s elected officials fled south with the Confederate army, taking the state archives with them.

For about a month, Flanagin went home to Arkadelphia, apparently assuming that the state government’s part in the war was over. Confederate authorities prevailed on him to reestablish the state government at the Hempstead County Courthouse in Washington, where the legislature met in 1864 to hear that the state war effort had collapsed. Thanks to judicial decisions authored by new state Supreme Court justice Albert Pike, this “rump” government was granted legal standing for its operations. One more brief flight to Rondo (modern Miller County but probably in Lafayette then) took place in 1864 when it appeared that Union general Frederick Steele would capture Washington. Steele, however, went to Camden (Ouachita County) instead, and the Confederates returned to their temporary capital.

Affairs in the Trans-Mississippi were in great disorder once the fall of Vicksburg left this section largely responsible for its own defense. Flanagin failed to attend the first Trans-Mississippi Department governors’ conference, made limited use of his executive powers, and did little to retard the rising peace sentiment among the masses. Both morale-building public speeches and aggressive executive actions were lacking. However, with most of the state either a no-man’s land or in the hands of the Federals, tax collections stopped, and with it the state’s source of revenue. Flanagin’s most energetic act was his rejection of a Confederate enrolling officer’s attempt to draft the clerk of the state Supreme Court. The most important effort to sustain the war was supplying the Washington Telegraph with newsprint, but this was undertaken by General Edmund Kirby Smith and not by Flanagin. Flanagin’s wartime correspondence contained letters from friends who apparently shared his belief that the war was lost. When criticized for his inactivity, he responded that he would never act “without or contrary to law.”

Flanagin did participate in the last governors’ conference held in 1865 following the news of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender. At that point, the governors decided to seek terms from the Federal government. Opposed to continuing the war or conducting guerrilla operations, Flanagin returned from Texas and suggested to Federal authorities that he be allowed to summon the old legislature, repeal all acts of secession, and then resign. Under Federal military auspices, Arkansas Unionists had written a new constitution in 1864 and installed a loyal governor, Isaac Murphy. Thus, the military never considered Flanagin’s proposal, which would have implied the legality of his regime. He was allowed to return the state archives and retire unmolested to Arkadelphia.

During the Reconstruction period, Flanagin tried to reestablish his law practice and participated little in state affairs. His correspondence indicates he opposed violence and took the same high legal and moral tone that had marked his gubernatorial career. In 1872, he was selected as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention.

After the Brooks-Baxter War, he was elected to the state convention that wrote the Constitution of 1874, serving as chairman of the judiciary committee. He was even spoken of as a possible gubernatorial candidate. He died, probably from congestive heart failure, on October 23, 1874, before the constitution’s final ratification, but he had signed an early draft. He was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Arkadelphia.

One enduring physical legacy was Flanagin’s law office in Arkadelphia. Erected about 1855 and not originally occupied by Flanagin, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. It survived the devastating tornado that destroyed much of Arkadelphia in 1997.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Donovan, Timothy P. Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press,1995.

Harris Flanagin Papers, 1861–1874. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Kie Oldham Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Newberry, Farrar. “Harris Flanagin.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 17 (Spring 1955): 3–20.

Yearns, W. Buck, ed. The Confederate Governors. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Military

Military Politics and Government

Politics and Government Harris Flanagin

Harris Flanagin  Flanagin Law Office

Flanagin Law Office  Hempstead County Courthouse

Hempstead County Courthouse

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.