calsfoundation@cals.org

Elections during the Civil War

Both Union and Confederate elections were held in Arkansas during the Civil War, including ones related to calls for secession and constitutional conventions in addition to the election of office holders, though turnout would decrease as the war progressed and both the ability to vote and interest in participating in elections diminished.

The election of 1860 set the stage for the Civil War in Arkansas. On the presidential ticket, Arkansans had a choice between John C. Breckenridge representing the southern wing of the Democratic Party, Stephen Douglas representing the Democrats’ northern wing, and John Bell of the new Constitutional Union party. (Abraham Lincoln, the candidate of the Republican Party, was not on the ticket in Arkansas.) Breckenridge would win in the state with fifty-three percent of the vote.

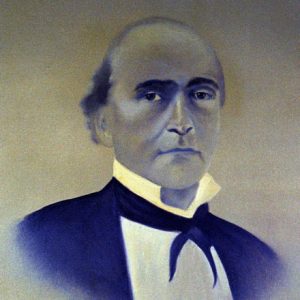

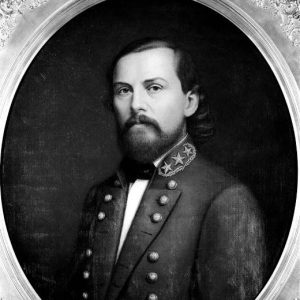

Perhaps more significant was the gubernatorial race in which Henry Rector, supported by congressman Thomas C. Hindman, ran against Richard H. Johnson, the candidate of “The Family,” a powerful group of Democrats that had dominated Arkansas politics since territorial days. Rector, who was related to members of the Family, was a gifted orator, while one newspaper called Johnson “the poorest stump speaker we ever listened to. He would save votes by quitting the stump.” When Arkansans voted on August 6, 1860, Rector defeated Johnson 31,578 to 28,622. He took office on November 15, and noting the election of Lincoln as president, stated in his inaugural address that “the states stand trembling upon the verge of dissolution.”

As southern states began to announce their secession from the Union following Lincoln’s win, pressure grew in the state to hold an election on whether to have a convention to determine Arkansas’s path. The Arkansas House of Representatives voted in favor of a convention on December 22, 1860, joined by the Senate on January 15, 1861. The election was set for February 18, 1861, with voters to decide whether to hold a convention and simultaneously to elect delegates. The decision to hold a convention was overwhelming, with 27,412 voting yes compared to 15,826 opposed. However, inspired perhaps by an early February crisis in which armed militias threatened to seize the U.S. Arsenal in Little Rock (Pulaski County), the majority of the delegates selected held Unionist views.

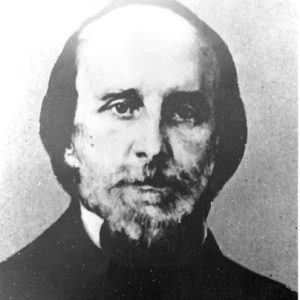

Meeting at what is now the Old State House in Little Rock in March and April, the delegates ultimately voted against secession, with thirty-five in favor and thirty-nine opposed. The convention then recessed until August 19, barring any change in conditions. However, on April 12, 1861, Confederate troops opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina; the fort surrendered the following day, leading Lincoln to call on the states for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion. Seeing that event as an attempt to coerce the seceded states back into the Union, convention chairman David Walker reconvened the body on May 6, and this time all but five of the delegates voted in favor of leaving the Union. Walker called on the five to change their votes to show unanimity, and only Isaac Murphy of Madison County refused.

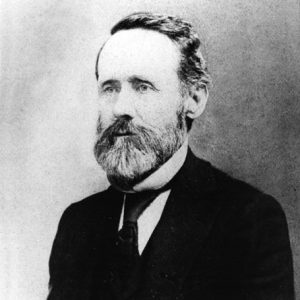

The secession convention also approved a new constitution, which was virtually identical to the 1836 constitution other than the words “Confederate States of America” replacing United States of America in the document. Convention members were not happy with the prospect of Rector as a wartime governor and approved a motion by Jesse Cypert that “the next general election for officers of this state, under this constitution, not otherwise herein provided for, shall be held on the first Monday in October, 1862,” thus shaving two years from the governor’s four-year term. That election pitted Rector against Harris Flanagin, then serving as colonel of the Second Arkansas Mounted Rifles in Tennessee, and James S. H. Rainey of Camden (Ouachita County). Flanagin won handily with 18,139 votes, while Rector received 7,419 and Rainey got 708. Confederate civil government in Arkansas, however, would prove to be ineffectual during the rest of the war.

A Union army led by Major General Frederick Steele occupied Little Rock on September 10, 1863, exiling the Confederate government to Washington (Hempstead County). Steele soon began taking steps to establish a Unionist government, following President Lincoln’s plan to create such a body once ten percent of the people who had voted in the 1860 election took an oath of loyalty to the United States. That threshold was met in January 1864, and delegates from twenty-four of Arkansas’s (then) fifty-seven counties gathered in Little Rock to create a new constitution. That document, which was similar to the 1836 constitution but repudiated secession and outlawed slavery, was submitted to voters along with a slate of officials on March 14–16, 1864, and approved 12,443 to 266, though only ten percent of Arkansans voted. Along with a new state legislature, Isaac Murphy, who had refused to change his vote at the secession convention and who was serving as Arkansas’s military governor, was elected governor. Elisha Baxter and William Fishback were selected by the legislature to serve in the U.S. Senate, though Congress ultimately refused to allow them to take office.

Arkansas’s Unionists apparently were not able to vote in the 1864 presidential election, but Union soldiers stationed in the state did. One officer in the Twenty-eighth Wisconsin Infantry Regiment observed from his camp at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) on November 8: “Election passed off quietly to-day. Co. ‘C’ polled 44 votes—all for Lincoln. The Regt. gives about 350 majority for ‘old Abe.’ There were a few McClellan votes—about 35 I think.” Lincoln defeated George B. McClellan 2.2 million to 1.8 million in the popular vote, including votes from Union soldiers from the twelve states that allowed absentee ballots that totaled 119,754 for Lincoln against 34,291 for McClellan.

Confederate governor Flanagin called his legislature into special session on September 22, 1864, and called for a general election to be held on October 3, but as historian Thomas A. DeBlack noted, “Most citizens in Confederate-held Arkansas had neither the time nor the inclination for politics.” Turnout was low among voters, most of whom were in refugee camps, though county officials and a new legislature were selected; the latter was never seated before the war ended in 1865, and Union officials declined to recognize the county officers.

For additional information:

Blackburn, George M., ed. “Dear Carrie,”… The Civil War Letters of Thomas N. Stevens. Mount Pleasant, MI: Clarke Historical Library, 1984.

Christ, Mark K., ed. The Die Is Cast: Arkansas Goes to War, 1861. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2010.

———. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Dougan, Michael B. Confederate Arkansas: The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Elisha Baxter

Elisha Baxter  William Fishback

William Fishback  Harris Flanagin

Harris Flanagin  Thomas Hindman

Thomas Hindman  Isaac Murphy

Isaac Murphy  David Walker

David Walker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.