calsfoundation@cals.org

Red River Campaign

The Red River Campaign involved a multipronged Union attack in southwest Arkansas and northwest Louisiana. The objectives—the capture of Texas to prevent Mexican Emperor Maximilian from threatening the region, the crippling of Confederate resistance west of the Mississippi, and the seizure of cotton land—failed as outnumbered Confederates maximized positions to repel the invasion. Afterwards, Confederate morale improved, bolstering further resistance in the Trans-Mississippi and prolonging the war.

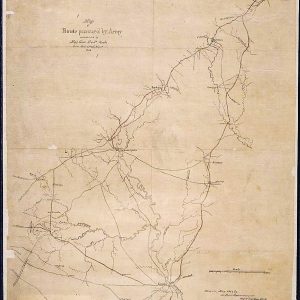

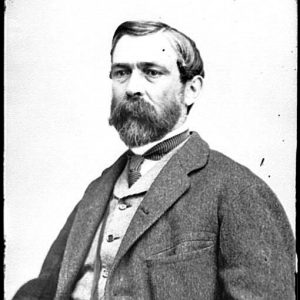

Under Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck’s plan, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks would march from west of New Orleans, link with Rear Admiral David Porter’s Mississippi Squadron on the Red River and infantry troops from east of the Mississippi River, and coordinate their movement into northwest Louisiana while Brigadier General Frederick Steele pushed south from Little Rock (Pulaski County). They would converge near Shreveport, Louisiana, before heading to east Texas. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, who replaced Halleck on March 9, questioned the strategy but allowed it because troops were already in motion.

The campaign began with Major General Andrew J. Smith’s detachment of the XVI Corps departing Vicksburg, Mississippi, to unite with Porter’s Mississippi Squadron near the mouth of the Red River in Louisiana. Banks’s command, consolidating at Berwick’s Bay, marched north to join Smith and Porter near Simmesport, Louisiana, under the auspices of Major General William B. Franklin. Arriving ahead of Franklin, Smith and Porter occupied Simmesport on March 13 before realizing the dangers caused by the Confederate position at Fort DeRussy on the Red River. Examining the problem, Smith’s troops successfully attacked the fortification. The convergence of Franklin, Porter, and Smith placed Confederate Major General Richard Taylor’s Alexandria, Louisiana, troops at a numerical disadvantage, forcing the Confederates to abandon Alexandria on March 15. Trying to gather intelligence on the Federal positions, Taylor exposed several small commands to individual attack. Noticing the emerging opportunity, Smith’s troops overwhelmed a Confederate detachment at Henderson’s Hill, giving Taylor another setback. When Grant ordered the return of Smith’s command eastward by April 10, Banks balked as Smith’s aptitude had proved an asset to Federal operations in Louisiana. Under pressure to move rapidly, Banks moved forward to Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Porter followed, forcing his ships over the treacherous falls at Alexandria.

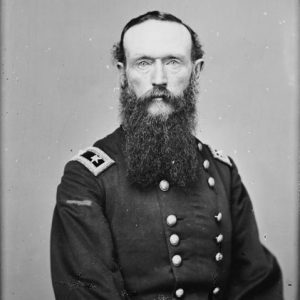

In Little Rock, Steele received orders to support Banks the day after the Fort DeRussy victory. Having argued against full backing from his position, Steele was not prepared, placing his command at a disadvantage. Undaunted, he ordered Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s Frontier Division at Fort Smith (Sebastian County) to consolidate with his column in Arkadelphia (Clark County) by April 1. Fearing a Rebel attack on his column en route, Steele directed Colonel Powell Clayton, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) garrison commander, to demonstrate against local Rebel forces. Dispatching two junior officers to distract the Confederates, Clayton’s detachments won another victory near Mount Elba (Cleveland County) on March 30, allowing Steele’s column to arrive in Arkadelphia unscathed.

At Grand Ecore, the Red River parted with the road Banks followed. Time dwindling, Banks disregarded proper reconnaissance and chose a route moving away from the river and Porter’s support. Taylor detected the Federal column marching April 6 out of Grand Ecore and understood the opportunity; his superior, Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith, disagreed with Taylor’s desire to strike the Federal column. Smith perceived Steele’s command as the greater threat and considered redeploying troops from Taylor’s army to Major General Sterling Price’s command in Arkansas. Enraged, Taylor acted against Smith’s strategy, assembling his men south of Mansfield, Louisiana, to try to trap Federal troops. Having skirmished with Confederates most of April 7, Brigadier General Albert L. Lee detected Taylor’s troops near Mansfield. Lee held a strong position, waiting for reinforcement. Banks, having arrived at Franklin’s headquarters April 7, moved toward the front on April 8 and ordered a direct assault without reconnaissance. Only after Lee protested did Banks reconsider and held his position. Taylor was forced to attack. In the engagement, Franklin’s order of march became problematic. Having placed each corps’s wagons behind its respective formations, the separated combat elements could not quickly pass these wagons. Hindered by Franklin’s mistake, the Federal troops retreated fifteen miles southeast and established a defensive position at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana. Taylor pursued, believing he could destroy the Federal force. On April 9, counterattacks at Pleasant Hill blunted the Rebel assault. But Banks lost confidence and ordered a retreat to Grand Ecore. On the Red River, Porter, battling low water, Confederate harassment, and obstructions at Loggy Bayou, determined to return to Grand Ecore because of a lack of progress. Confederates surprised Porter’s squadron from the riverbank at Blair’s Plantation on April 12 but inflicted little damage on the vessels.

Waiting three days in Arkadelphia for Thayer, Steele continued southwest without him on April 1. Using the Military Road to march toward the new state capital at Washington (Hempstead County), Federal troops reached the Little Missouri River on April 3. With provisions dwindling, no contact from Thayer, and a growing Confederate force in his front, continuing to Shreveport appeared doubtful. Undeterred, Steele marched forward, searching for a better tactical position and hoping to find Thayer. Flanking the Confederates off the riverbank on the Little Missouri via Elkins’s Ford and continuing forward, Steele made contact with Thayer on April 5. Since leaving Little Rock, Steele’s men had been on half rations, and Thayer’s force further stressed the supplies. Continuing to Shreveport appeared impossible. Viewing the map, Steele saw an opportunity in Price’s position. Believing Steele’s objective was Washington, Price had his men working on a trap at Prairie D’Ane, placing most of the Confederates in the region across Steele’s front. On April 10, Steele shoved Price southward at Prairie D’Ane, opening the Washington-Camden Road to the east. Thinking Federal troops were falling for the trap, Price did not fully suspect the possibilities of Steele’s directional shift and failed to block it. Using the Washington-Camden Road, on April 16 (during the Skirmish at Camden), Federal troops easily seized the fortified town of Camden (Ouachita County), where Steele believed he could resupply his army before continuing south to support Banks.

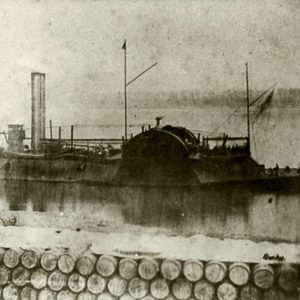

At Grand Ecore, Banks had lost his momentum and began to withdraw. E. K. Smith seized this opportunity to dispatch three infantry divisions to Arkansas on April 15. With his force reduced to 5,000 men, Taylor lacked the ability to destroy Banks in retreat, yet he continued harassing the Union, which began withdrawing toward Alexandria on April 21. The Confederates blocked the Federal line of retreat at Monette’s Ferry, Louisiana, on the Cane River, in an attempt to halt withdrawal while striking the Union’s rear. Before Taylor could strike, Federal troops found an unprotected ford and flanked the Confederates off the ferry crossing on April 23. On the Red River, Porter’s fleet, struggling with low water, departed Grand Ecore on April 17. Forced to scuttle the Eastport because of torpedo damage, the remaining naval elements arrived at Alexandria by April 27.

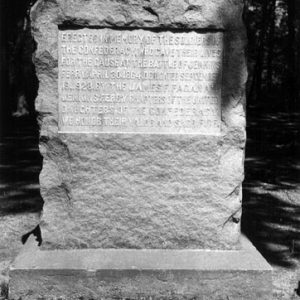

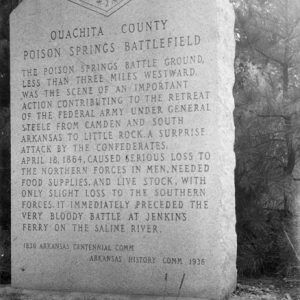

Back in Arkansas, Steele had found Camden devoid of needed supplies. Price refused to attack the town directly, instead harrying communication and supply lines. Trying to find rumored sources of corn, Steele sent a column west of Camden. On April 18, 1864, Confederates surprised the returning foragers at Poison Spring (Ouachita County), overwhelming the column and depriving Steele of supplies, men, wagons, and livestock. Surprisingly, provisions arrived April 20 from Pine Bluff. Three days later, Steele dispatched a column toward Pine Bluff. On April 25, Confederates at Marks’ Mills overran the column. Steele slipped out of Camden the night of April 26, marching toward Little Rock.

Arriving at Jenkins’ Ferry in the Saline River bottoms on April 29, Steele began building a pontoon bridge. Confederate cavalry engaged the rearguard, halting as darkness fell and reengaging at dawn. The Confederate divisions from Louisiana began arriving April 30 to join Price’s command. The Federal rearguard took a strong position, anchoring its flanks between a flooded creek and swampy woodland. The Confederates assaulted the Federal lines piecemeal, failing to break it. By 12:30 p.m., E. K. Smith ended the assault, and Steele slipped across the river. He arrived May 2 in Little Rock, and his part of the campaign, also known as the Camden Expedition, was over.

Union Major General David Hunter arrived in Alexandria on April 27, bearing dispatches and added verbal emphasis from Grant. Ordered to divert and concentrate on other targets, Banks’s first objective became getting his army back to safety before redeployments could begin, meaning further retreat from Alexandria. Facing the falls at Alexandria in low water, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, the XIX Corps’s chief engineer, organized Banks’s men and constructed dams to narrow the river and raise the water. On May 9, an accident nearly damaged the dams, and in haste, Porter ordered the Lexington through the opening. The rest of the squadron negotiated the falls over the next three days, and the Union continued to retreat with the squadron shadowing its march.

Taylor’s Confederates continued harassing the retreating Federal troops, unsuccessfully engaging them at Mansura, Louisiana, on May 16 and Yellow Bayou, Louisiana, on May 18. Once the Union troops reached the Atchafalaya River, they discovered water blocking their retreat. Lacking pontoons, Bailey constructed a floating bridge by aligning the naval vessels and connecting them with planks. The final soldiers crossed the river on May 20.

Federal losses surpassed 8,700. The absence of troops from eastern and western theaters prevented Grant from applying stronger pressure on more valuable targets in 1864. The Confederate victory was marginal. While Rebels repelled the Union invasion, they failed to destroy its columns in Arkansas and Louisiana and lost about 6,500 men.

For additional information:

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission, 1967.

Christ, Mark K., ed. “This Day We Marched Again”: A Union Soldier’s Account of War in Arkansas and the Trans-Mississippi. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2014.

Forsyth, Michael J. The Camden Expedition of 1864 and the Opportunity Lost by the Confederacy to Change the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003.

———. The Red River Campaign of 1864 and the Loss by the Confederacy of the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2002.

Joiner, Gary. Through the Howling Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and Union Failure in the West. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006.

Joiner, Gary, ed. Little to Eat and Thin Mud to Drink: Letters, Diaries, and Memoirs from the Red River Campaigns. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2007.

Robertson, Henry O. The Red River Campaign and Its Toll: 69 Bloody Days in Louisiana, March–May 1864. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2016.

Smith, Michael Thomas. “‘For the Love of Cotton’: Nathaniel P. Banks, Union Strategy, and the Red River Campaign.” Louisiana History 51 (Winter 2010): 5–26.

Derek Allen Clements

Pocahontas, Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.