calsfoundation@cals.org

Skirmish at Camden (April 15, 1864)

| Location: | Camden |

| Campaign: | Red River Campaign |

| Date: | April 15, 1864 |

| Principal Commanders: | Brigadier General Eugene Carr, Brigadier General Samuel Rice (US); Brigadier General J. O. Shelby, Colonel Colton Greene (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | VII Corps, Third Division, Third Brigade (US); Shelby’s Cavalry Brigade, Greene’s Cavalry Brigade (CS) |

| Casualties: | Unknown |

| Result: | Union victory |

The Skirmish at Camden on April 15, 1864, occurred after Union brigadier general Frederick Steele had forced Major General Sterling Price’s troops and cavalry out of Camden (Ouachita County) on April 12. Realizing his opportunity, Steele marched his army approximately forty miles to the east toward Camden. This would prove to be an important turning point within the Red River Campaign for the Union troops.

In the early hours of April 15, the Thirty-third Infantry of Iowa began its march toward Camden, still eighteen miles away. Its first movement on the Confederate lines forced a battery on the main road to cease firing, allowing the troops to continue advancing toward the city. By 10:30 a.m., the Thirty-Third Infantry had marched through skirmishes for roughly three hours. These skirmishes would slow down the advancing troops, but the Confederate forces knew it would be impossible to prevent Steele’s army from entering Camden. Nearing the end of the skirmishing, the Confederates realized it would be necessary to move south in order to avoid becoming pinned down within the city.

During Steele’s march, Maj. Gen. Price’s cavalry pursued, attacking the front and rear of the forces in an attempt to halt Steele’s entrance into Camden. Although a nuisance to the Union forces, the attack ended in failure, stemming from Price’s quick and uncoordinated effort. The delay, however, was a psychological victory for the Confederacy. By the afternoon of April 16, the entire Union brigade entered the town, having complete control.

Low morale and food shortage hampered the Union troops as they entered the town. It even became necessary to forage as food supplies dwindled in camp. The delay cost the Union troops and made it nearly impossible to venture too far from their fortifications. Prior to their arrival, Steele requested thirty days of rations for his troops set to arrive at Camden by April 15. The Adams and Chippewa, the steamers sent to provide supplies, did not meet their deadline. The Adams sank close to its home port, while the Chippewa sustained damage and returned home. In town, Camden residents “dumped animal carcasses in many local wells,” practically eliminating any means of having drinking water for the troops. At the same time, Union troops knocked on doors, demanding food from all Camden residents. Steele hastily stepped in, halting his troops from pillaging. It would be a few days before any supplies arrived, leaving Steele and his men to conservatively utilize supplies and attempt foraging expeditions.

While the Union dealt with poor morale, troops established a light fortification line around Camden with the hopes of keeping the Confederacy at bay until their supplies arrived. Steele needed to contact Union general Nathaniel Banks, who was leading the column in northwestern Louisiana, with the understanding that he would not be falling into a trap by fortifying his troops within the city. Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Kirby Smith provided a morale boost for the Confederates as he began his move of three infantry divisions to Camden.

The true fighting would occur on April 16–18, 1864, as Steele realized the need to attack the Confederate troops before reinforcements could arrive. April 15, however, laid the groundwork for an important series of skirmishes during the overall campaign.

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Forsyth, M. J. The Camden Expedition of 1864 and the Opportunity Lost by the Confederacy to Change the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2003.

Sperry, A. F. History of the 33rd Iowa Infantry Volunteer Regiment: 1863-6. Des Moines: Hills & Company, 1866.

Sutherland, D. E. “1864: ‘A Strange, Wild Time.’” In Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas, edited by Mark K. Christ. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Matthew Thomas Whitlock

Old Dominion University

Camden Expedition

Camden Expedition Civil War Timeline

Civil War Timeline Military

Military ACWSC Logo

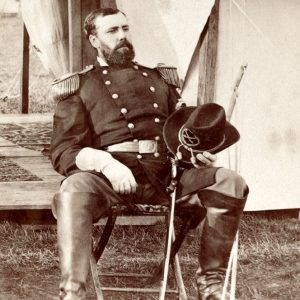

ACWSC Logo  Eugene Asa Carr

Eugene Asa Carr

My family lived near White Oak Creek just north of where the state park is. My great-great-grandfather Charles Featherston Walthall, along with twelve other men, contested the crossing of Eugene Carr’s advance guard of the VII Corps. Charles was captured after the 3,000 cavalry men overran the position held by the thirteen Confederate infantry. Charles was at the first battle of Poison Springs. Charles was at the occupation of Camden. Charles was held prisoner in the county jail for the duration of the occupation of twelve days. Charles was with the Union retreat to Jenkins’ Ferry. Charles was with the Federal retreat all the way back to Little Rock. Charles was confined there on May 3rd. Charles was shipped north to St. Louis, and then to the arsenal at Rock Island. Charles was denied medical care. He was malnourished and was inadequately housed and clothed. Charles died at Rock Island on Nov. 10, 1864. He is buried in grave 1603. He left behind a wife and three small children. Charles’s brother Edward was captured at Ft. Donelson, and died as a POW at Camp Douglas. One of Charles’s children was William Jethro Walthall, who grew up to be the State Superintendent of the Assembly of God Church–twice. Charles’s daughter grew up, got married, and had several children. Charles’s son Andrew Joseph was my great-grandfather. My grandfather was named Charles. My uncle Charles died as a young child. And I am named Charles. My grandmother was very adamant that we all remember that after my grandfather was taken away, the Union army stripped his home of personal possessions. They left my great-great-grandmother Mary Jemima in her slip. And soon made a widow of her…