calsfoundation@cals.org

Pulaski County

| Region: | Central |

| County Seat: | Little Rock |

| Established: | December 15, 1818 |

| Parent County: | Arkansas |

| Population: | 399,125 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 758.31 square miles (2020 Census) |

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

1,921 |

2,395 |

5,350 |

5,657 |

11,699 |

32,066 |

32,616 |

47,329 |

63,179 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

86,751 |

109,464 |

137,727 |

156,085 |

196,685 |

242,980 |

287,189 |

340,597 |

349,660 |

361,474 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

382,748 |

399,125 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

199,197 |

49.9% |

| African American |

143,548 |

36.0% |

| American Indian |

2,226 |

0.6% |

| Asian |

10,035 |

2.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

225 |

0.1% |

| Some Other Race |

18,600 |

4.7% |

| Two or More Races |

25,294 |

6.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

33,153 |

8.3% |

| Population Density |

526.3 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$51,749 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$32,692 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

16.8% |

|

Pulaski County has a diverse population, economy, natural setting, and social structure influenced by state and local government, business and industry, and finance and nonprofit sectors. Three of Arkansas’s six natural divisions converge in Pulaski County—the Ouachita Mountains, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (the Delta), and the Coastal Plain—representing the state’s wealth of flora, fauna, and geological features. Located in central Arkansas, Pulaski County is one of the state’s five original counties and has been at the center of state government, politics, business, art, and culture for almost two centuries.

Pre-European Exploration

The Plum Bayou culture flourished in central Arkansas between AD 600 and 1050, as can be seen in sites such as the Plum Bayou Mounds Archeological State Park in Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke counties). By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Quapaw were the dominant tribe in the part of Arkansas that would soon become Pulaski County. In 1818, the Quapaw signed a treaty restricting them to one million acres between the Arkansas and Ouachita rivers, and in 1824 they ceded this land in exchange for land they would share with the Caddo along the Red River in northern Louisiana. Eventually, they were relocated to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma.

European Exploration and Settlement

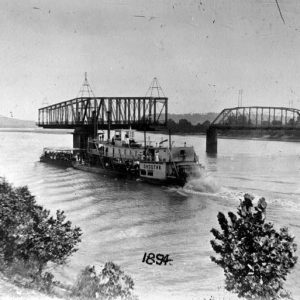

Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto led an expedition through Arkansas between 1541 and 1542, although it is unlikely that he visited Pulaski County in these two years. Between 1721 and 1722, Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe, a French explorer, traveled up the Arkansas River through Pulaski County. He noted a rock formation which he called “Le Rocher Francais” (meaning the French rock), where he inscribed the French king’s coat of arms on a tree trunk on April 9, 1722, thus claiming for France the north bank of the Arkansas River in central Pulaski County. Eventually, this bluff claimed by La Harpe would become known as the Big Rock, and a smaller but more famous formation across the river would be designated the “Little Rock.” La Harpe’s French rock became the site of an army post called Fort Roots in 1897, a facility later converted to a veterans hospital. The little rock on the south bank of the river was, in 1872, cut up in order to serve as the abutment for a railway bridge that ended up not being built; the Junction Bridge was later constructed on the site.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In 1812, Congress established Missouri Territory, which reached south to Louisiana. Two of the territory’s southern counties (Arkansas and Lawrence) included much of the area that would become Arkansas. When Congress established Arkansas Territory in 1819, the two counties were divided into the five original Arkansas counties. Pulaski County was established at that time and named for Count Casimir Pulaski, a Polish nobleman who fought and died in 1779 in the Revolutionary War’s Battle of Savannah. The territorial legislature voted in 1821 to move the capital from Arkansas Post to Little Rock (Pulaski County) because of flooding and disease at the former location. The legislature had, in 1820, established Cadron, a fur-trapping post on the Arkansas River which was located in what is now Faulkner County, as the county seat but moved it to Little Rock in 1821 when it chose to move the territorial capital there. The new state constructed a capitol building in Little Rock on the Arkansas River bank between 1833 and 1842, and state government operated out of what is now called the Old State House until the present capitol was completed in 1915. County government operated out of the statehouse until 1883, when the state government came to require the entire building and displaced the county government to a temporary location. County officials began planning and building the Pulaski County Courthouse, completed in 1889.

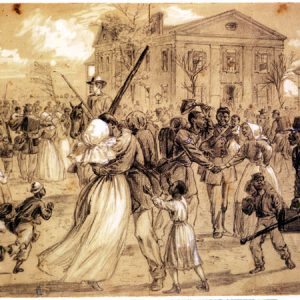

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census recorded the white population of the county at 8,187 with 3,505 people held in bondage. Seven free people of color also lived in the county. The importance of large-scale agriculture to the economy of the county is demonstrated by the large proportion of the population held in slavery, with nearly thirty percent enslaved.

The secessionist movement dominated Arkansas and Pulaski County politics in 1860 and 1861, leading up to the Civil War. The Little Rock Arsenal was seized by pro-secession militia units from across the state in February 1861. Members of the Capital Guards, the Little Rock militia unit, helped prevent the outbreak of violence between the other militias and the Federal troops at the arsenal. Delegates at the Secession Convention, held at the Old State House, voted almost unanimously on May 6, 1861, to secede from the Union. Pulaski County sent two representatives to the convention, Augustus Hill Garland and Joseph Stillwell, and both men were slave owners. Arkansas formally joined the Confederacy on May 20, 1861.

Little Rock remained the state capital, but in 1863, as the Union army approached, the capital was moved to Washington (Hempstead County). Union forces led by General Frederick Steele prevailed in the Little Rock Campaign in September 1863, defeating Confederate troops led by General Sterling Price. Engagements in the campaign include the Action at Bayou Meto, Engagement at Bayou Fourche, Skirmish at Shallow Ford, and Skirmish at Ferry Landing. As Federal units threatened the city, Confederate brigadier generals John Sappington Marmaduke and Lucius Walker fought a duel northeast of Little Rock, leading to the death of Walker. Union forces occupied Pulaski County for the rest of the war.

Both sides constructed fortifications in the county during the war. Isaac Murphy, sole member of the Secession Convention not to support the state leaving the Union, was inaugurated as the Unionist governor of the state in 1864 after the adoption of a new constitution. Other engagements in the county include Skirmish at Benton Road, Skirmish at Huntersville, and Skirmish at Little Rock. The Little Rock National Cemetery opened in 1866 and holds the remains of many soldiers who died in the state during the Civil War and other conflicts.

The period immediately following the war saw the first of a number of incidents of extrajudicial violence in the county. An African American man named Hugh Johnson was lynched in 1865 after allegedly assaulting a white woman.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

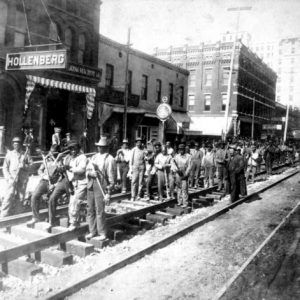

The population surged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Little Rock and North Little Rock’s populations increased significantly, and several small crossroad settlements grew into Alexander, Jacksonville, Levy, Mabelvale, Roland, and Scott. In 1890, the city of Little Rock derailed the community of Argenta’s plans to incorporate as a city by annexing the community as Little Rock’s Eighth City Ward.

Fort Logan H. Roots was constructed on the north bank of the Arkansas River in the 1890s to replace the Federal military presence formerly based at the Little Rock Arsenal.

Incidents of extrajudicial violence continued to occur in the county, with many of the events racially motivated. A mob killed Jim Sanders in 1882 after he allegedly attacked a white woman. That same year, a man known only as Smith reportedly lost his life after being accused of attacking a white woman. A decade later, Henry James was killed after allegedly attacking a white child. The lynching of an unknown African American woman in 1894 was reported in multiple newspapers, but it is unclear of what crime she was accused. The Argenta Race Riot of 1906 followed the deaths of two Black men the previous month, with another three killed during the violence.

However, African Americans were far from victims in Pulaski County at this time. An independent Black community had emerged along West Ninth Street in Little Rock. Too, African American members of the Knights of Labor carried out a strike in 1886 at a plantation in the southern part of the county that, although unsuccessful, signaled a growing willingness to challenge white authorities.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1904, Little Rock’s Eighth Ward split off to become part of North Little Rock, a separate municipality. In 1906, the city’s name was formally changed to Argenta but then reverted back to its present-day name, North Little Rock, in 1917.

World War I prompted the construction of the Little Rock Aviation Supply Depot and the Little Rock Intermediate Air Depot, in addition to the Picric Acid Plant, a munitions plant that produced the highly explosive chemical picric acid. Camp Pike, constructed near North Little Rock, trained troops during the war and was eventually renamed Camp Joseph T. Robinson. The installation continues to serve as an Arkansas National Guard base in the twenty-first century.

The final lynching to occur in Pulaski County was of John Carter in 1927. Racial tensions ran high in the county after the murder of a white girl in late April, culminating in the murder of Carter; thousands of whites rioted in the heart of the Little Rock African American community on West Ninth Street. The incident occurred while Pulaski County, and the state as a whole, were being affected by the Flood of 1927.

Other major events in this era included the construction of Lake Winona, completed in 1938 as Little Rock’s principal municipal water supply, and the establishment of the Little Rock Housing Authority on October 5, 1940, which provided low-cost rental housing for many families moving to Little Rock during and after World War II.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Camp Robinson was reactivated in September 1940 due to the start of World War II, and central Arkansas communities grew due to the growing presence of soldiers and industries designed to serve their needs. Little Rock was also a recruitment center for the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps. After the war, new factories opened in the county, but labor conditions led most of the employees of the Southern Cotton Oil Mill to go on strike on December 17, 1945. A few days later, a strikebreaker killed one of the striking workers.

The crisis over the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in 1957 was the most significant news event in the county in the twentieth century. Considered the first major test of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas decision, the crisis foreshadowed the civil rights turmoil that the nation faced throughout the 1960s. The crisis also revealed deep division among local and state leaders, affecting their capacity to grow the local economy. The deaths of twenty-one African American boys in a fire at a reform school in Wrightsville in 1959 led to no meaningful change in race relations in the state. Failure to achieve fuller school integration led to the short-lived College Station Freedom School in the predominantly Black area of College Station in 1970.

In 1952, the county was chosen for a Strategic Air Command base in Jacksonville; it opened September 10, 1955, as Little Rock Air Force Base. Other events of note include the construction of the Governor’s Mansion, completed in 1950; Little Rock Municipal Waterworks’ construction of Lake Maumelle, completed in 1958; and the establishment of the global headquarters of non-profit organizations Lions World Services for the Blind (1947) and Heifer Project International (1971).

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform

In the last three decades of the twentieth century, the county’s population growth slowed while surrounding counties’ growth quickened. Despite these trends, Pulaski County developed as a multimodal transportation hub. The interstate highway system was completed in Arkansas with Interstate 30 and Interstate 40 intersecting in North Little Rock. In the 1970s, cross-town Interstate 630 was completed in Little Rock, and the I-430/I-440 loops were completed around Little Rock and North Little Rock. The December 3, 1970, completion of the McClelland-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System opened the Arkansas River to barge traffic, and Little Rock and North Little Rock developed port facilities on each side of the river. In the last half of the twentieth century, the Adams Field airport in Little Rock grew to a 640-acre development named Little Rock National Airport (now the Bill and Hillary Clinton National Airport) with more than $170 million in capital improvements. Winrock International is headquartered in North Little Rock.

About eighty-five percent of Pulaski County’s population lives in incorporated areas of its eight cities: Alexander, Cammack Village, Jacksonville, Little Rock, Maumelle, North Little Rock, Sherwood, and Wrightsville. Unincorporated communities include Marche, Sweet Home, Little Italy, Ferndale, Landmark, McAlmont, Woodson, Hensley, and Morgan.

Industry

Dillard’s Inc. has its headquarters in Pulaski County, and Alltel, a telecommunications company, was also based in Pulaski County until it merged with Verizon Wireless. Stephens, Inc., one of the largest off–Wall Street investment banking companies, is headquartered in Little Rock. In November 2004, the William J. Clinton Presidential Library opened on the banks of the Arkansas River in Little Rock.

Major health facilities such as the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Baptist Health Medical Center, John L. McClelland Veterans Affairs Hospital, CHI St. Vincent, and the Arkansas Heart Hospital are all in Little Rock. These institutions serve most of the state but also attract patients and researchers worldwide.

Government

Pulaski County performs the typical functions that other Arkansas counties perform but also provides many services not often performed by other counties, including housing, community and economic development in unincorporated areas, and youth development programs for at-risk children.

Most local government issues transcend local boundaries. Consequently, the municipal and county governments in Pulaski County have formed cooperative governmental service organizations. They include the Rock Region Metropolitan Transit Authority, which provides public transportation; the Central Arkansas Library System (CALS), which provides library services for Pulaski and Perry counties; Central Arkansas Water, which provides municipal water service to all the municipalities of Pulaski County and parts of Saline County; Metroplan, which serves as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for federal highway appropriations and programs; the Multi-Purpose Civic Center Facilities Board, which owns and operates the 18,000-seat Simmons Bank Arena (known until 2009 as Alltel Arena and then as Verizon Arena until 2019) in North Little Rock; and the Pulaski County Bridge Public Facilities Board, which developed the Junction Bridge into a pedestrian/bicycle bridge in the River Rail Project area of downtown Little Rock and North Little Rock. The Arkansas State Library is located in Little Rock, where it supports library services throughout the state while also providing direct library services.

Education

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Pulaski County had three public school districts: the Little Rock School District, the Pulaski County Special School District, and the North Little Rock School District. In 2014, Jacksonville and northern Pulaski County approved a proposal to detach from the Pulaski County Special School District to form a new district. What eventually became the Arkansas State School for the Deaf opened in Little Rock in 1867, and the Arkansas School for the Blind (ASB) moved from Arkadelphia (Clark County) to Little Rock in 1868; in 1939, the ASB campus was relocated from Center Street to 2600 West Markham Street, where it remains in the twenty-first century.

Former educational institutions in the county include Little Rock University, Draughon School of Business, St. John’s Seminary, Little Rock College, St. Johns’ College, and Maddox Seminary.

In an attempt to make education available to freedmen after the Civil War, Philander Smith College was established in Little Rock in 1877. Shorter College (1895) and Arkansas Baptist College (1884) were established to serve predominantly Black student bodies. In 1927, leaders established Little Rock Junior College, which began offering four-year degrees as Little Rock University in 1957; it became the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UA Little Rock) in 1969. The University of Arkansas (UA) assumed management of a Little Rock–based, privately established nonprofit medical school in 1879 and merged it into the public university in 1911. The medical school became UAMS, which provides graduate- and professional-level education. University of Arkansas-Pulaski Technical College is a comprehensive two-year college. The University of Arkansas at Little Rock Bowen School of Law is one of two law schools in the state and is located in a building originally constructed to house UAMS.

Attractions

The Arkansas Travelers, one of two minor league baseball teams in the state, play at Dickey-Stephens Park in North Little Rock. War Memorial Stadium hosts football and soccer games, as well as concerts and other events. Appearing in the film Gone with the Wind, the Old Mill in North Little Rock is a favorite location for photographers. Pinnacle Mountain State Park gives visitors breathtaking views of the Arkansas River. Numerous museums operate in the county, including Esse Purse Museum, Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum, Arkansas National Guard Museum, Historic Arkansas Museum, Jacksonville Museum of Military History, Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History, Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, and Museum of Discovery. The National Register of Historic Places includes many sites in the county, including the Ten Mile House, the Pike-Fletcher-Terry House, Dunbar Junior and Senior High School and Junior College, and Curran Hall.

For additional information:

Capital County: Historical Studies of Pulaski County, Arkansas. Little Rock: Pulaski County Historical Society, 2008.

Pulaski County Historical Review. Little Rock, AR: Pulaski County Historical Society (1953–).

Ron Copeland

Pulaski County Government

Joe Foster

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.