calsfoundation@cals.org

Historic Arkansas Museum

aka: Arkansas Territorial Restoration

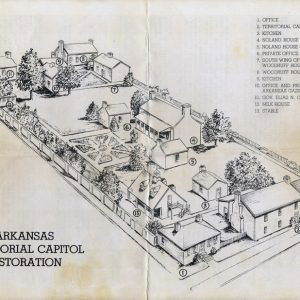

What is now the Historic Arkansas Museum (HAM) opened in 1941 as the first state-supported history museum in Arkansas, under the name Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration, commonly shortened to Arkansas Territorial Restoration. Originally consisting of a half-block of historic houses in downtown Little Rock (Pulaski County), the museum site has expanded to the equivalent of two city blocks and now features a wide array of programs, too. The first history museum in Arkansas accredited by the American Association of Museums (1981), the Historic Arkansas Museum has become—with the Old State House—the de facto state history museum. Its mission emphasizes the frontier period and the work of Arkansas’s artists and artisans from prehistoric times to the present.

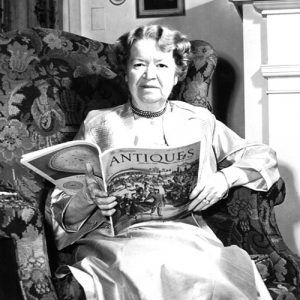

Pioneering preservationist Louise Loughborough founded the museum in 1939. Loughborough knew of the historic houses on the east half of Block 32, original city of Little Rock, including the Hinderliter House, thought to be the meeting place of the last territorial assembly, which she labeled “Territorial Capitol.” She described Little Rock as the “town of three Capitols” as a part of the public relations campaign for the museum. The Hinderliter is the oldest house still standing in central Arkansas (circa 1827) and was built as a grog shop (tavern) by Jesse Hinderliter. When the city threatened to condemn these houses, Loughborough began a campaign to save them, garnering the support of the state, the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA), and private sources. Act 388 of the 1939 General Assembly created the Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration Commission, naming Loughborough as chairwoman. With the help of architect and artist Max Mayer, she directed the restoration of the half-block of houses, placing them in a park-like setting surrounded by the downtown commercial district. The museum opened on July 19, 1941, featuring the “Territorial Capitol” (Hinderliter House) and three other antebellum structures sporting the names of prominent Arkansas pioneers Charles Fenton Mercer Noland, William E. Woodruff, and Elias N. Conway.

Loughborough said one of the goals of the restoration project was to show the “courage and fineness” of those sent to Arkansas to govern the territory. Restored and furnished to the preservation standards of the day, the site became a model of historic preservation for the state and a precedent for the state’s commitment to its history. In 1960, the National Trust for Historic Preservation honored the museum as one of twelve outstanding museum communities in the nation.

In 1961, architect Edwin B. Cromwell inherited the leadership of the museum from Loughborough and began expanding the site to provide more space for programs and to cushion the original half-block from urban development. With federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) funds matched by the state legislature, the adjoining half-block was acquired with the old Fraternal Order of Eagles Building, which became the museum’s reception center. The expansion to its current size used federal highway enhancement funds and state and private sources. The Hinderliter House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 5, 1970.

In 1972, the museum began to move toward a professional staff and began reexamining its mission and programs in light of continuing research and changing museum and preservation standards. Research found only circumstantial evidence for the association of the Hinderliter House with the last territorial assembly and led the museum to change the names associated with the Noland and Conway houses to the Brownlee House and McVicar House, due to their associations with Robert Brownlee and James McVicar, respectively. Using probate inventories, newspaper advertisements, and other period sources, the museum created furnishing plans for the museum houses. The research in material culture exposed a void in the academic study of Arkansas’s artists and artisans, which the museum moved toward filling in the award-winning two-volume study, Arkansas Made: A Survey of the Mechanical, Decorative and Fine Arts Produced in Arkansas, 1819–1870, by Swannee Bennett and William Worthen (1990, 1991). The museum has amassed the most extensive and best-documented collection of Arkansas-made objects, including portraits by Edward Payson Washbourne, Henry Byrd, and George Catlin; knives made by James Black; and other items including firearms, pottery, furniture, silver, and photography.

The museum adopted policies and procedures reflecting museum standards, becoming in 1981 the first history museum in the state accredited by the American Association of Museums. The museum continued to refine the site, moving the antebellum Plum Bayou Log House from its original location near Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke Counties) in 1976 and sponsoring archaeological investigation on buildings and landscape features on Block 32.

In 2001, the museum changed its name to the Historic Arkansas Museum. It also opened a new Museum Center, doubling the size of the old reception center, with 10,000 square feet of exhibits, a theater, a hands-on history room, an entrance atrium, and other amenities. A meticulous 2010 reconstruction of the 1823 original Woodruff Print Shop is also part of the grounds. On May 31, 2019, the museum was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Arkansas Territorial Restoration Historic District.

HAM features regular changing exhibits on a host of topics. Educational programming serves the school and adult population, and an active research and collecting program continues to preserve the objects and stories of the state’s history.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Territorial Restoration Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places registration form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed May 12, 2025).

Bennett, Swannee, and William Worthen. Arkansas Made: A Survey of the Mechanical, Decorative and Fine Arts Produced in Arkansas, 1819–1870. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990–1991.

Harrison, Eric E. “Hoisting a Historic Salute.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 17, 2016, pp. 1E, 6E.

Historic Arkansas Museum. https://www.arkansasheritage.com/historic-arkansas-museum/ (accessed May 12, 2025).

Koon, David. “Renaissance Man.” Arkansas Times, August 4, 2016, pp. 14–16, 18–20, 22. Online at https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2016/08/04/renaissance-man (accessed May 12, 2025).

Lake, Douglas, and C. Allan Brown. A Garden Heritage. Little Rock: Arkansas Territorial Restoration Foundation, 1983.

Worthen, William B. “Louise Loughborough and Her Campaign for ‘Courage and Fineness.’” Pulaski County Historical Review (Summer 1992): 26–33.

———. “Restoring the Restoration.” History News (November 1984): 6–11.

William B. Worthen

Historic Arkansas Museum

Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration Map

Arkansas Territorial Capitol Restoration Map  Blacksmith Shop

Blacksmith Shop  John Drennen

John Drennen  HAM Center

HAM Center  Hinderliter Grog Shop

Hinderliter Grog Shop  Hinderliter House - Modern View

Hinderliter House - Modern View  Historic Arkansas Museum

Historic Arkansas Museum  Louisa Loughborough

Louisa Loughborough  McVicar House

McVicar House  pARty for Peg Sculpture

pARty for Peg Sculpture  Plum Bayou House Moving

Plum Bayou House Moving  Plum Bayou Restoration

Plum Bayou Restoration  Plum Bayou Restoration

Plum Bayou Restoration  Woodruff Print Shop

Woodruff Print Shop  Woodruff Home and Print Shop Postcard

Woodruff Home and Print Shop Postcard  Woodruff Printing Press

Woodruff Printing Press

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.