calsfoundation@cals.org

Negro Boys Industrial School Fire of 1959

aka: Wrightsville Fire of 1959

On March 5, 1959, twenty-one African American boys burned to death inside a dormitory at an Arkansas reform school in Wrightsville (Pulaski County). The doors were locked from the outside. The fire mysteriously ignited around 4:00 a.m. on a cold, wet morning, following earlier thunderstorms in the same area of rural Pulaski County. The institution was one mile down a dirt road from the mostly Black town of Wrightsville, then an unincorporated hamlet thirteen miles south of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Forty-eight children, ages thirteen to seventeen, managed to claw their way to safety by knocking out two of the window screens. Amidst the choking, blinding smoke and heat, four or five boys at a time tried to fight their way forward through the narrow openings as the fire began to devour them. Survivors never forgot the horror of that fire. The wife of one of the survivors later said, in an interview before her husband’s death from cancer, that he had continued to dream about the fire.

The event brought attention to this largely forgotten institution that was operating during the Jim Crow era in Arkansas. Founded in 1923, the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School (NBIS) was, for most of its existence, a juvenile work farm located first outside Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and then, in the mid-1930s, outside of Wrightsville.

The institution became “Exhibit A” for the disparities that prevailed in Arkansas during segregation. Throughout the history of segregation, government employees, historians, and sociologists documented differences in the philosophy and physical structures of the white and Black institutions in the state. For example, the 1940 biennial report to the governor notes the following vocational trades taught at a white boys’ school: “carpentry and joining, cabinet work, glazing, painting cement work, brick laying, wood and metal lathe operation, blacksmithing, acetylene welding, plastering, tailoring and shoe mending.” NBIS is mentioned only once—as the recipient of 156 mattresses made by the white boys’ trade school. By the time of the fire, the differences had only marginally narrowed.

A 1956 report by sociologist Gordon Morgan documented the horrific conditions at Wrightsville. It was not merely that “vocational education suffers greatly at the school.” The squalor was mind boggling: “Many boys go for days with only rags for clothes. More than half of them wear neither socks nor underwear during [the winter] of 1955–56….[It is] not uncommon to see youths going for weeks without bathing or changing clothes.” At times, the number of boys at the “school” was over 100. There was no laundry equipment. A single thirty-gallon hot water tank served the bathing needs of the entire population. The water was deemed undrinkable. Employees brought their own drinking water to work.

As an institution for Black male delinquents and orphans in an era in which penal conditions were particularly notorious for their routine cruelty and corruption, Wrightsville resembled in some unsettling ways the infamous Arkansas adult prison farm in southeastern Arkansas, popularized in the 1980 movie Brubaker. Wrightsville had all the hallmarks of a junior prison work farm in the making. At the time the decision was made to move NBIS to Wrightsville, the Arkansas General Assembly formally decided that the best treatment for Black boys sentenced to the institution was farming. Morgan, the sociologist who had worked on the 1956 report on the school, would later become the first tenured African-American professor at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He wrote in his master’s thesis on NBIS that, in an earlier era, armed guards had overseen the boys in the fields. Boys were whipped with a leather strap for infractions.

The deteriorating condition of the physical plant at Wrightsville may have been a significant cause for the 1959 fire. “All buildings…are in need of extensive repairs, particularly the boys’ living quarters,” Morgan noted in 1956. As Wrightsville was supposed to be as self-sustaining an operation as possible, the emphasis was on farm yields. Maintenance was in short supply or non-existent. Governor Orval Faubus would admit weeks after the fire that faulty wiring may have contributed to the fire.

Although he was noticeably disturbed by the deaths of twenty-one children, the governor acted immediately to guard against their deaths being used as a possible political weapon against him. Even though he had visited NBIS in the past year and had publicly noted its deteriorating condition, he had failed to propose an increase in appropriations to address the issue. In characteristic fashion, the governor went on the attack, insinuating at his press conference the morning of the fire that the blame for the deaths of the boys lay squarely of the shoulders of Lester R. Gaines, the Black superintendent. Gaines, he implied, had failed to ensure the safety of the boys by having an employee at the building at night in case of emergency. The reality would be more complicated.

Clearly expecting the board of directors for the school to rubber-stamp his conclusion that Gaines was at fault, Faubus appointed the remaining three members to conduct an immediate hearing to determine where the blame lay. To his obvious chagrin, after interviewing certain employees, his board—whose members he had appointed himself—concluded that Superintendent L. R. Gaines had acted properly and that “everyone had attempted to carry [out] his duty.” The board did nothing more than recommend a “severe reprimand” for the employee who was supposed to be in charge of the supervision that night.

In fact, a careful reading of the admissions and contradictory statements by Gaines given publicly to the press and at the hearing in the days after the fire reveals, at a minimum, negligence and other wrongdoing on the superintendent’s part. At the same time, the Wrightsville institution, through no fault of the superintendent, was dangerously short-staffed, especially in comparison to Pine Bluff. On the night of the fire, the institution for white boys in Pine Bluff had two house parents on duty, and the doors at that institution were not locked at night. The governor told reporters that Wrightsville had a high incidence of escapes, which accounted for the difference in policy. Additionally, Gaines had appeared in person to make the dormitory’s deteriorating condition known to a state legislative sub-committee.

In response to the finding of the board, Faubus angrily announced that he would “get to the bottom” of the controversy and would conduct his own investigation. Within two weeks, he called another press conference, recommending to the board that it terminate Gaines, Gaines’s wife, and one other employee. He told reporters that he had evidence that Gaines had gotten certain employees together before the board’s hearing and pressured them into fabricating a story that would absolve him of responsibility. Two employees had allegedly come to the Governor’s Mansion to talk to Faubus privately and had changed their stories about their duties. According to the governor, both men said that the superintendent had permitted them to go home for the night after seeing that the boys were in bed and locking them in, since they had worked all day.

Gaines responded by refusing to back down, telling the press that he was hired by the board and would not resign unless its members called for his resignation. Eleven employees publicly supported their superintendent by signing a statement that was carried in its entirety in the Arkansas State Press, the largest statewide African-American newspaper in Arkansas. Published by civil rights activists (and founders of the Arkansas State Press) L. C. and Daisy Bates, editorials in the paper were the only public display of support within Arkansas for Gaines. At its next meeting, the board chairman, Alfred Smith, announced the termination of employees recommended by the governor, including Gaines.

Governor Faubus insisted that the matter not rest there. He instructed his attorney to turn over the investigative material he had assembled to the prosecuting attorney’s office. A Pulaski County grand jury questioned witnesses but returned no criminal indictments. In its final report, the grand jury made the following statement:

The blame can be placed on lots of shoulders for the tragedy: the Board of Directors, to a certain extent, who might have pointed out through newspaper and other publicity the extreme hazards and plight of the school; the Superintendent and his staff, who perhaps continued to do the best they could in a resigned fashion when they had nothing to do with [it]; the State Administration, one right after another through the past years, who allowed conditions to become so disreputable; the General Assembly of the State of Arkansas, who should have been so ashamed of conditions that they would have previously allowed sufficient money to have these conditions corrected; and finally on the people of Arkansas, who did nothing about it.

Clearly, the fire had caused embarrassment in the state. Its citizens, however, generally saw the deaths of the twenty-one boys not as a consequence of the state’s continuing commitment to the policy of white supremacy, but rather as a result of negligence. At an earlier Arkansas Claims Commission hearing, individual family members had been awarded a few hundred dollars each for the deaths of their loved ones; white attorneys representing the families received as much as fifty percent of the damages awarded by the commission. Living in Chicago, Illinois, at this time, Gaines did not return to Little Rock to defend his actions, nor did he testify before the grand jury.

After the initial publicity died down, the fire was largely forgotten by the public until fifty years later, when Frank Lawrence, a brother of one of the victims, brought the deaths of the boys again to the attention of the state. Attempting to make a documentary film about the fire, Lawrence was joined by family members and others who sought some kind of closure on behalf of their families.

Significantly, reaction to the deaths of the boys from outside Arkansas at the time of the fire was in sharp contrast to the response of people living inside the state. The governor received thirty letters from citizens around the country, almost all from outside the South. Responding to wire-service accounts in newspapers, the outraged correspondents interpreted the deaths as part of an ongoing pattern of behavior that began in 1957 during the Central High Crisis and said so in scathing language. Representative of these views was a telegram from the Greater King Solomon Baptist Church in Detroit, Michigan: “We hold you and the Jim Crow system of the South just as responsible for the burning of the Negro children in Little Rock as if you had struck the match. We pledge to fight until you and the subhuman racialism you represent are thrown into the garbage dump of history.”

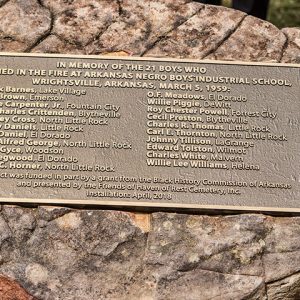

On April 21, 2018, a monument was placed in Haven of Rest Cemetery in Little Rock, where fourteen of the twenty-one victims—those who could not be identified—had been buried in an unmarked mass grave. Those buried at the site were: Lindsey Cross (age fourteen), Charles L. Thomas (fifteen), Frank Barnes (fifteen), R. D. Brown (sixteen), Jessie Carpenter Jr. (sixteen), Joe Crittenden (sixteen), John Daniel (sixteen), Willie G. Horner (sixteen), Roy Chester Powell (sixteen), Cecil Preston (seventeen), Carl E. Thornton (fifteen), Johnnie Tillison (sixteen), Edward Tolston Jr. (fifteen), and Charles White (fifteen). The seven who had been identified and buried separately were: Roy Hegwood, Willie Piggee, John Alfred George, Henry Daniels, Amos Gyce, O. T. Meadows, and Willie Lee Williams. On April 25, 2019, a monument to the dead was unveiled at the Wrightsville Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction.

For additional information:

“Fire Kills 21 Boys Shut in Dormitory at Training School.” Arkansas Gazette, March 6, 1959, pp. 1A–2A.

Moritz, John. “Monument Honors Boys Killed in Fire.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 26, 2019, pp. 1B, 5B.

Peacock, Leslie Newell. “Stirring the Ashes.” Arkansas Times, February 28, 2008, pp. 10–12 Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/stirring-the-ashes/Content?oid=949040 (accessed November 26, 2025).

Pettit, Emma. “Marker Placed at Last for Lost Boys.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 22, 2018, pp. 1B, 4B.

Stockley, Grif. Black Boys Burning: The 1959 Fire at the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2017.

———. “The Negro Boys Industrial School Fire: A Holistic Approach to History.” Pulaski County Historical Review 56 (Summer 2008): 39–54.

———. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. “The Twenty-One Deaths Caused by the 1959 Fire at the Arkansas Negro Boys Industrial School: An Isolated Case of ‘Neglect” or an Instance of Racial Violence?” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Up from the Grave: Arkansas’s Deadliest Fire. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2019/06/us/up-from-the-grave/ (accessed November 26, 2025).

Williams, L. Lamor. “Families Remember Boys Killed in ’59 Fire, Still Hope for Answers.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 6, 2009, pp. 1B, 3B.

Grif Stockley

Little Rock, Arkansas

Those who were responsible for this horrific event should have been punished and sued. None of us are truly free until we are all free! My heart goes out to families of these victims. It seems like this wouldn’t have happened if they did their job. Tell the truth and shame the devil.

I’m thirty-one years old and was born in 1993, but today was the day I learned about this. They don’t teach you these things in history class. Some people still think African Americans and Blacks are “upset about stuff that happened 400 years ago” but Jesus Christ, my mom was born before this.

I was only five years old when my oldest brother (Johnny Tillison, age sixteen) was one of those boys who were killed in that fire in 1959. I am now seventy years old in the land of the living, and I pray that one day the truth will be revealed concerning that matter.

I was born the next day, March 6, 1959, and never learned this tragic story all the years of my life. Well, the wretched beliefs of those who caused the deaths and neglected the truth are not abandoned by some. But the arc of history bends toward justice, as King said.

When my thirteen-year-old brother died in 1959 at Wrightsville Boys Reform School, along with twenty other African American boys, I was only twelve years old. Now, I am sixty-seven years old, and no one takes the blame for this tragedy. My brother died in this fire because of a bicycle. He was the youngest youth in that school. I know a change will come one day. When JESUS comes, he will have the last word.

It’s been 65 years. Are you all still praying? If so, what are you praying for?

Justice will be served one day for those young boys tragically killed like this. Those monsters responsible will definitely reap what they sow. May they all continue to rest in peace, and my heart and prayers are with their families.

William Lloyd Piggee is my thirteen-year-old brother, and he lost his life over a bicycle. I would like justice for all of those precious African-American young boys who never stood a chance. Perhaps justice will be rewarded one day when Jesus comes. My prayer is that this story is told and that everyone responsible for the deaths of all of those young black boys will answer one day. I forgive them, but I will never forget my brother and those who lost their lives. As I viewed all of those young men in the paper, one thing was obvious: they were all African American youth.

My uncle was one of the boys killed in the fire: Willie Lee Williams. My family is currently obtaining information from relatives about what happened during this time.