calsfoundation@cals.org

John Carter (Lynching of)

aka: Lonnie Dixon (Execution of)

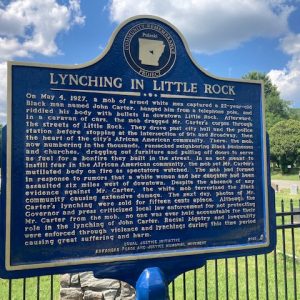

In early May 1927, Little Rock (Pulaski County) experienced a wave of mob violence surrounding the lynching of an African American man named John Carter, an event that was closely connected with the conviction and execution of a Black teen. Carter’s lynching and the rioting that followed is one of the most notorious incidents of racial violence in the state’s history. This event reveals much about the history of race relations in Little Rock, as well as the state’s struggle with its national image.

The episode began on April 30, 1927, when the dead body of a white girl named Floella McDonald (described as anywhere between eleven and thirteen years of age) was discovered by a janitor, Frank Dixon, in the belfry of the First Presbyterian Church in Little Rock, following a massive, three-week search effort by law enforcement, citizens, and civic organizations. Police detained the janitor and his sixteen-year-old son, Lonnie Dixon, the latter based largely on information offered by another young white girl, Billie Jean Kincheloe, who said he had talked to her that day, too. Police reported obtaining an oral confession from the younger Dixon after questioning him for nearly twenty-four hours, during which he had no food, rest, or legal counsel, and after they told him they had detained his mother because he had not been truthful. They charged him with criminal assault and murder. Dixon reportedly recanted that confession the next day.

Realizing the outrage present in the city, the police secretly transported both Dixons on a circuitous route to different destinations, eventually incarcerating the teen at the Texarkana (Miller County) city jail. This tactic proved to be prudent, as that night thousands of people gathered outside Little Rock City Hall and the state penitentiary, determined to seek revenge against the Dixons. Carloads also traveled to jails in Benton (Saline County), Hot Springs (Garland County), Malvern (Hot Springs County), Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Sheridan (Grant County), searching for them.

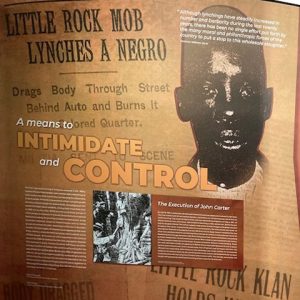

After the oral confession but before a grand jury had met to indict Dixon, the prosecuting attorney, A. Boyd Cypert, and the Little Rock Bar Association both released statements saying that anyone over age fourteen could be subject to the death penalty. Although mob activity in the city dissipated over the next few days, tensions over the murder of Floella McDonald remained high. Then, on May 4, a Black man allegedly assaulted a white woman and her daughter six miles west of downtown Little Rock. An armed posse quickly formed and searched the countryside for him. After finding him (or the person they assumed to be him) later that day, the angry mob hanged the man, identified as John Carter (whom sources reported as age twenty-two or thirty-eight), from a telephone pole and shot him. A caravan of cars then dragged the man’s mangled corpse through the streets of Little Rock, stopping at the intersection of 9th and Broadway, which at the time was the heart of the city’s African American community, West Ninth Street.

For the next several hours, an estimated 5,000 white people (including, according to reports, women carrying babies) rioted in the intersection and surrounding neighborhood. Carter’s body was set ablaze, with doors and furniture from neighborhood businesses and churches serving as fuel. As a result of warnings from the city’s Black leaders, including Scipio A. Jones, no local residents ventured into the streets, although one Black man was seized and beaten and almost thrown onto the pyre. Three hours after the rioting began, Governor John Martineau deployed the Arkansas National Guard to the scene, and upon arrival, they found a member of the mob directing traffic with a charred arm that had been broken off of Carter’s body. Soon thereafter, the crowd dispersed. The next day, the police detained a boy on Main Street for selling pictures of John Carter’s lynched body for fifteen cents a copy.

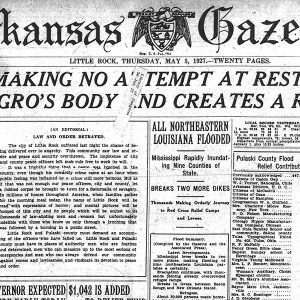

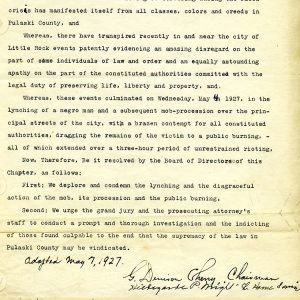

Local leaders—including Martineau, newspaper editors, businessmen, clergy, and several organization leaders (including those of the Red Cross)—strongly condemned the lynching and rioting. A grand jury was convened to investigate the incident, but it deadlocked and was dismissed without issuing indictments after half resigned in protest. The lynching also received immediate coverage from the national media, whose attention was already focused on Arkansas because of the devastating Mississippi River Flood of 1927. Consequently, local leaders were very concerned about damage to the state’s image and the negative impact that the lynching might have on the flood relief efforts.

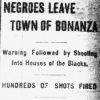

Anxiety continued in Little Rock for the next several weeks. Dozens of African American residents reportedly fled the city, some leaving the state entirely, including the local editor of the Chicago Defender. The Board of Censors banned the Defender and another out-of-state Black newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, from circulation out of fear that they were inflaming racial tensions.

On May 17, Lonnie Dixon was arraigned—again without legal counsel present—pleaded not guilty, and accused a friend, Eugene Hudson, of the murder. Then, on May 19, with 200 National Guardsmen and 150 special deputy sheriffs protecting the courthouse because of bomb threats and rumors of another lynching, Lonnie Dixon was tried for murdering Floella McDonald. Two days before the trial, Dixon’s attorneys, who had been chosen by lot, had neither seen the indictment nor formulated a strategy. As the sole witness in his own defense at the trial, Dixon repeated his “not guilty” plea and blamed the friend. The jury deliberated for as little as seven minutes, according to some reports, before declaring Dixon guilty and sentencing him to death.

The next month, two days before his execution, Dixon signed a new confession that implicated the friend. Then, the night before his execution, he reportedly dictated a third confession—this time blaming only himself—in the presence of the prosecuting attorney, warden, and two ministers, but with no legal counsel yet again. He was executed by electrocution on June 24, 1927, his seventeenth birthday.

Although it would be over twenty-five years until Little Rock experienced another major episode of racial unrest—the Central High Crisis—the lynching of John Carter left immediate scars on the city’s residents that would not heal for decades. On June 13, 2021, a marker commemorating the lynching was unveiled at Haven of Rest Cemetery, near the site where Carter was first hanged, and also the place where some believe his remains were buried.

Authors Marcet and Emanuel Haldeman-Julius published a fictionalized treatment of the lynching of Carter in 1929; the book, titled, Violence: A Novel of Love and Justice in the Central South, was released by Simon and Schuster but proved commercially unsuccessful.

For additional information:

Eison, James Reed. “Dead, But She was in a Good Place, a Church.” Pulaski County Historical Review 30 (Summer 1982): 30–42.

Eley, Ashton. “Victim of 1927 Lynching Remembered.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 14, 2021, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/jun/14/victim-of-1927-lynching-remembered/ (accessed November 4, 2024).

Greer, Brian D. “A Flood of Fear: Little Rock and the Lynching of John Carter.” Research Paper. Tom W. Dillard Black Arkansiana Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Little Rock, Arkansas.

———. “The Last Lynching: A New Look at Little Rock’s Last Episode of Deadly Mob Justice.” Arkansas Times. August 4, 2000, pp. 12–19.

Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. “The Story of a Lynching: An Exploration of Southern Psychology.” Haldeman-Julius Monthly 6 (August 1927): 3–32, 97–103.

———. The Story of a Lynching: An Exploration of Southern Psychology. Little Blue Book No. 1260. Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius. Girard, KS: Haldeman-Julius Publications, 1927.

Harp, Stephanie. “On Being Involved.” In Slavery’s Descendants: Shared Legacies of Race and Reconciliation, edited by Dionne Ford and Jill Strauss. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019.

———. “Stories of a Lynching: Accounts of John Carter, 1927.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018. Online at https://www.ncis.org/sites/default/files/TIS%20Vol.6%20Feb2020_EISENSTEIN2019_HARP_STORIES%20OF%20A%20LYNCHING_ACCOUNTS%20OF%20JOHN%20CARTER%201927.pdf (accessed November 4, 2024).

Jennings, Jay. Carry the Rock: Race, Football, and the Soul of an American City. New York: Rodale, 2010.

“John Carter and Lonnie Dixon: Remembering 1927.” Central Arkansas Library System YouTube channel, February 2, 2021. Available here (accessed December 4, 2025). [see Related Web Video in sidebar]

Lewis, Todd. “Mob Justice in the ‘American Congo’: ‘Judge Lynch’ in Arkansas during the Decade after World War I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Summer 1993): 156–184.

McClinton, Edith W. Scars From A Lynching. Rev. ed., edited by Stacey James McAdoo and Christie Ellision-Thompson. N.p.: 2000.

Miller, Jennifer Singleton. “Looking for John Carter: The Story of One Year.” MFA thesis, Pacific University, 2010.

Minton, Clifford E. America’s Black Trap. Gary, IA: Alpha Book Company, 2001.

Brian D. Greer

Washington DC

Stephanie Harp

Bangor, Maine

I was talking to an older gentleman today (in 2008) about how race and racism have changed over the past several decades. The killing of Emmett Till was mentioned, and, later, he mentioned this case. As he remembered the details of the crime, it started because a horse and buggy had gotten out of control with a white woman and child in it. A black man, I guess John Carter, ran after them and tried to help stop the runaway horse and buggy. Some white men assumed that he was trying to attack the woman and her daughter. Even though the woman tried to tell the men that the black man was trying to help them, the white men killed him. Then they dragged his body past Bethel AME church on 9th and Broadway.

In the 1990s, I was an RN for an outpatient clinic. We had an elderly white man refuse a needed blood transfusion because we couldn’t guarantee the donor was white. When pressed for his reasons, he related that he was a member of the Arkansas Guard. He then described with detail the hanging of John Carter and the events that followed. The Gazette story attached reports the Guard “restored order.” He said he was called up that night. Their duty was to prevent anyone from taking Carter’s body down from the utility pole. The body was to remain on display and not removed for his family. He expressed a great deal of pride in his duty. He left Against Medical Advice, continuing to refuse a blood transfusion.

My grandparents, mother, and aunt were part of the exodus of blacks from Little Rock caused by this incident. My grandfather was almost torn apart by dogs used by the mob. They saw the body of John Carter dragged in front of their house.