calsfoundation@cals.org

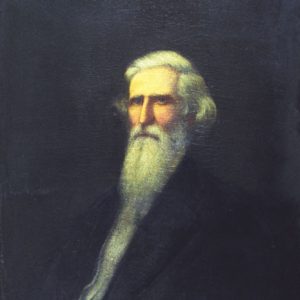

Henry Massie Rector (1816–1899)

Sixth Governor (1860–1862)

Henry Massie Rector was the state’s sixth governor. He was part of Arkansas’s political dynasty during the antebellum period, but he was not always comfortable in that role and played a part in its downfall.

Henry Rector was born on May 1, 1816, at Fontaine’s Ferry near Louisville, Kentucky, to Elias Rector and Fannie Bardell Thurston. He was the only one of their children to survive to maturity. Elias Rector, one of the numerous Rectors who worked as deputy surveyors under William Rector, the surveyor-general for Illinois and Missouri, served in the Missouri legislature in 1820 and as postmaster of St. Louis, Missouri. He also surveyed in Arkansas and acquired, among other speculations, a claim to the site of the hot springs in the Ouachita Mountains prior to his death in 1822 (a claim that led to the court case of Rector v. United States).

Rector received the rudiments of an education from his mother, but his formal schooling was limited to two years spent at Francis Goddard’s school in Louisville. His mother remarried after his father’s death, and from age thirteen to nineteen, Rector spent an obviously unhappy childhood at the salt-works of his stepfather, Stephen Trigg, cutting and hauling wood. Trigg was also the executor of Elias’s estate, and one lawsuit, Postmaster-General of U.S. v. Trigg [36 US 173 (1837)], reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1834. At stake was a judgment of $1,595.53, an enormous sum at the time.

In 1835, at age nineteen, Rector left for Arkansas to try to salvage his inheritance. The move placed him in a position to assume prominence, in part because of his land holdings but also because of his relationship to the first and fifth governors, James and Elias Conway. Ann Rector Conway, their mother, was Rector’s aunt. In addition, he had two cousins, Wharton Rector and Elias Rector, who were prominent in the affairs of the territory. He tried to secure title to his father’s claim to what is now Hot Springs (Garland County), but in 1876, after decades of litigation, the government confirmed individual claims to land around the springs but reserved the springs for public use.

In October 1838, Rector married Jane Elizabeth Field of Louisville, a niece to former territorial governor, John Pope. They had four sons, Frank N., William, Henry J., and Elias W., and four daughters, Ann Baylor, Julia Sevier, Fanny Thruston, and Ada E. His wife died in 1857, and he married Ernestine Flora Linke three years later. They had one child, Ernestine Flora.

It was doubtless largely due to William Field, a nephew to Governor Pope and a major stockholder in the Real Estate Bank, that the young and inexperienced Rector was appointed teller in the State Bank at Little Rock in 1839. In 1841, the bank having failed under his tellership, Rector moved to a plantation near Collegeville (Saline County) to farm and study law. In 1842, in obviously desperate straits, he accepted appointment from President John Tyler as U.S. marshal for the district of Arkansas, a position he held throughout Tyler’s term. (No one serious about a political future took a job under Tyler, but it was highly and briefly profitable since Arkansas generated a huge legal business, and marshals were paid by the fee system.) In 1848, he was elected to the Arkansas Senate, representing Perry and Saline counties. In his two terms, he devoted considerable attention to problems at the state penitentiary and acquired a reputation as a skilled debater. In 1852, he was chosen a Democratic presidential elector.

From 1853 to 1857, Rector served as U.S. surveyor general for Arkansas. In 1854, he moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where he practiced law and carried on extensive farming operations along the Arkansas River. He was elected in 1854 to a term in the Tenth General Assembly, representing Pulaski County in the House of Representatives. In 1859, he was elected to the state Supreme Court, where his rulings were singularly inept.

Despite his considerable kinship connection with that politically powerful dynasty known as “The Family” (made up of the Johnson, Conway, and Sevier families), Rector seems to have managed to offend most of his kin, even to the point of suing them and publicly differing from them on key political issues. The Family dominated state politics in the antebellum period, having established itself as the friend of the common man. Until the 1850s, the Family had neutralized competition in the Democratic Party.

However, the enormous growth of population severely challenged the Family’s dominance. A young Mississippi firebrand, Thomas Carmichael Hindman, forced his way into Congress and then launched a campaign to capture a seat in the U.S. Senate. Following Hindman’s moves closely, Rector saw his opportunity in 1860 to wrest the office of governor away from the regular Democratic Party nominee, Richard Mentor Johnson, the brother of U.S. Senator Robert Ward Johnson. Family strategists had forced the selection of Richard H. Johnson as the party’s gubernatorial nominee and essentially wrote the party platform and secured six of their members as delegates to the national convention.

As the election season of 1860 got underway, no one seemed poised to challenge Johnson in the governor’s race until Rector announced as an Independent Democrat. The exact connection between Hindman and Rector was not clear at the time. Hindman had suffered a major setback when it had been proved that he wrote his own “puffs” and when he had failed to show up for a duel with Robert Ward Johnson. But Hindman either loaned or sold his newspaper, The Old-Line Democrat, to Rector, along with his hired editor, Thomas C. Peek, who subsequently married one of Rector’s nieces. (Later, in 1862, Peek edited the short-lived Daily State Journal, one of the few pro-Rector papers in the state.)

In the campaign that followed, Rector had three advantages. First, there was built up resentment over the long years of Family control. Rector ran, despite all his genealogy, as an outsider, or in Peek’s words, “a poor honest farmer of Saline County, who toils at the plow handles to provide bread, meat and raiment for his wife and children.” Although Rector managed mostly to make a good deal of noise, Johnson was such a poor speaker that he usually cost himself votes. Rector managed to come up with an implausible plan for state aid for railroads by “giving” the lines the state debt; at first he was for public education, but when it was pointed out that schools cost money, he reversed himself and supported a tax cut. Confused voters in the end made Rector the sixth governor with 31,518 votes to Johnson’s 28,662.

Rector’s inauguration, during which a noisy crowd went to his home and “liquored,” coincided with the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln as president. Lincoln’s views on slavery were unacceptable to all candidates in Arkansas, and he was not even on the ballot, but otherwise Lincoln’s election was strictly constitutional. Rector, in his first address to the legislature, claimed that the North had no right to elect a Northerner and hence, the Union now being dissolved, Arkansas was independent. Silence greeted this eccentric theory. The gubernatorial election had not focused on slavery or secession, primarily because Johnson and Rector mostly agreed on the topic. Not until it was apparent that South Carolina would act independently did Arkansas’s Southern nationalists organize. This group included such disparate and previously hostile men as Thomas C. Hindman, Albert Pike, and the Johnsons, but it did not include Rector. His one contribution to the movement came when he approved the General Assembly’s provision for a special election on February 18, 1861, to elect delegates to a convention to decide whether to secede. This bill had been kept hidden until the very end of the session, after many of the legislators had departed for home. In late January, a rumor circulated that Federal reinforcements were headed for Little Rock and that Governor Rector wanted volunteers to come stop them and take the Federal arsenal. The call for troops had come out of Rector’s office, but the governor claimed he was innocent of planning to start the Civil War in Little Rock. The Federal commander, native son Captain James Totten, did agree to evacuate the Little Rock Arsenal, but the onslaught of negative publicity helped ensure defeat for secessionist candidates at the February 18 election. Voters approved summoning a convention by a narrow margin, but they elected a majority of anti–immediate secessionists to it. The convention assembled on March 4, 1861, and chose David Walker as chairman. The anti-secessionists blocked a move to secede immediately but approved calling for an election on August 5, 1861, to allow a vote of the people. This amounted to a compromise, for extreme secessionists from the southern counties were threatening to secede from the state.

Arkansas remained in the Union, albeit tenuously, until the firing on Fort Sumter forced the issue. When Lincoln called for volunteers after the fall of Fort Sumter, Rector refused: “The people of this commonwealth are freemen, not slaves,” he said with unconscious irony, “and will defend to the last extremity their honor, lives and property against Northern mendacity and usurpation.” In the post-war glow that overcame the South, historian Josiah H. Shinn wrote of these words: “No stronger State paper has ever been issued from the executive department at Little Rock, nor, for that matter, from any State department in all the world.” It was Rector’s greatest moment.

Walker reconvened the Secession Convention in Little Rock on May 6, 1861, and it voted to secede from the Union. Rector presided over the mobilization of the state but lost control of the process as the Family and its conservative allies flexed their muscles. A note in Rector’s hand read: “Col. Webb says that when the convention meets they will try to declare my office vacant. Oh Hell.” Fearing the damage Rector might do as commander in chief, instead they created a state military board to rein in the governor. The convention even debated deposing Rector but instead hoped that the creation of the board and a new constitution (that of 1861) that scheduled a gubernatorial election in 1862, would be adequate.

Conservatives hoped to transfer the Arkansas army directly into the Confederacy, but B. C. Totten, a states’-rights Democrat, surprised everyone by siding with Rector, thus enabling the governor to frustrate much of the transfer. Throughout the remainder of his term, Rector embraced state’s rights and denigrated Confederate authority from Richmond. By fall of 1861, the Arkansas army for the most part had gone home, leaving the state undefended even as many Union supporters joined an anti-war group called the Peace Society. The first Confederate general in the state to have problems with Rector, William J. Hardee, took his enlistees across the Mississippi River into Tennessee; the second general, Earl Van Dorn, who also quarreled with Rector, followed up his defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge by embarking his troops for Shiloh in Tennessee, although he arrived too late to take part in that battle. Rector’s response, printed on May 8, 1862, was a proclamation promising to “build a new ark and launch it upon new waters” if the Confederacy did not respond to Arkansas’s abandonment in the face of a Federal invasion into northeastern Arkansas.

Secession from secession did not play well, and when Thomas C. Hindman, now a major general, arrived, things changed quickly. A proponent of total war, Hindman would not brook any states’-rights arguments. Indeed, his military tyranny during the summer of 1862 exceeded anything on either side. Left in the shadows, Rector discovered that his enemies wanted the election promised in the Constitution of 1861. The state Supreme Court agreed, and Rector, all the while cursing one and all, ran again only to be defeated on October 6, 1862, by Harris Flanagin, a former Whig but one with ties to the Family. Flanagin’s campaign consisted of staying with his regiment in Tennessee; Rector tried to justify his record and denounced Flanagin for being an Irishman (which he was not). The vote, 18,187 to 7,419, was a decisive defeat for the governor. When the General Assembly met on November 3, 1862, Rector resigned. After his application for a commission in the Confederate army was rejected, he volunteered in the state reserve corps for the rest of the war.

At the war’s end, only the pillars to the gate were left of his once-fine plantation outside of Little Rock. He then returned to farming and hauled cotton in wagons from his plantations in Hempstead, Garland, and Pulaski counties to Little Rock. He waged many court battles over his Hot Springs claims but did not win the big prize of securing fully his father’s claim. Augustus H. Garland, Robert Ward Johnson, and Albert Pike were among his many attorneys. Rector lost, both in the Court of Claims and on an appeal [Hot Springs Cases, 92 U.S. (2 Otto) 698 (1876)] but did salvage most of the land not in the government reservation. His latter days were spent in Hot Springs, and he seems to have used a shotgun to assist him in collecting his rents. Part of the town’s later folklore was to attribute to Rector’s ghost any unexplained explosion.

Rector was a delegate from Garland County to the constitutional convention in 1874 but played little role in either the overthrow of the Republicans or the triumph of the Redeemers. He did make an appearance in an Opie Read story after that author had written that the accidental firing of the old cannon at the state house had killed Bradley Bunch. Rector invited Read to his home and there confronted him with the living Bunch. The three celebrated the event with well-aged whiskey.

Rector died on August 12, 1899, in Little Rock and is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery. He was, in the sagacious judgment of William Minor Quesenbury, “a violent man who fights people.” Not only did his two years in office reflect this, but he also pistol-whipped his sons’ schoolteacher because the man had disciplined one of his children. Calling the man a “damned stinking Yankee,” he added, “You strike my son like I would a negro, you god damned miserable Yankee dog.” In retrospect, some would say his greatest moment came in defying Lincoln’s call for troops. But in unifying a largely frontier state for the first modern war, he proved to be seriously lacking.

For additional information:

Brown, Walter L. “The Henry M. Rector Claim to the Hot Springs of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Winter 1956): 281–292.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Dougan, Michael B. Confederate Arkansas: The People and Policies of a Frontier State in Wartime. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

Kie Oldham Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Moneyhon, Carl H. “Governor Henry Massie Rector and the Confederacy: States’ Rights versus Military Contingencies.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73 (Winter 2014): 357–380.

Shinn, Josiah H. Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas. Chicago: Genealogical and Historical Publishing Company, 1908.

Yearns, W. Buck, ed. The Confederate Governors. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985.

Jeannie Whayne

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Waddy W. Moore

Conway, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in The Governors of Arkansas, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. The Governors of Arkansas is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.