calsfoundation@cals.org

Sevier County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County Seat: | De Queen |

| Established: | October 17, 1828 |

| Parent Counties: | Hempstead, Old Miller |

| Population: | 15,839 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 563.57 square miles (2020 Census) |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

634 |

2,810 |

4,240 |

10,516 |

4,492 |

6,192 |

10,072 |

16,339 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

16,616 |

18,301 |

16,364 |

15,248 |

12,293 |

10,156 |

11,272 |

14,060 |

13,637 |

15,757 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17,058 |

15,839 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

9,594 |

60.6% |

| African American |

578 |

3.6% |

| American Indian |

478 |

3.0% |

| Asian |

65 |

0.4% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

248 |

1.6% |

| Some Other Race |

3,088 |

19.5% |

| Two or More Races |

1,788 |

11.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

5,508 |

34.8% |

| Population Density |

28.1 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$47,704 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$22,320 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

21.3% |

|

Sevier County is located in southwestern Arkansas and borders the state of Oklahoma. The county is located at the northern limits of the Gulf Coastal Plain. Sevier County has four rivers, each of which is impounded by a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers lake. The Little River forms the southern boundary, while the Saline River borders the east side of the county. The Cossatot River and Rolling Fork River both flow from north to south.

Pre-European Exploration

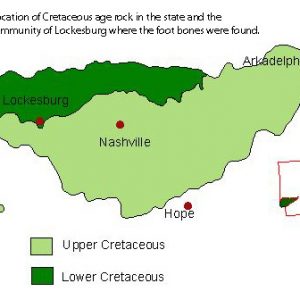

Dinosaur bones discovered in the county in 1972 led to the identification and description of Arkansaurus fridayi. In 2017, the Arkansaurus fridayi was named as the official state dinosaur.

Artifacts indicate that human activity in Sevier County dates back as much as 10,000 years; for most of that time, these inhabitants lived by hunting and collecting foods. The county’s rivers and streams, especially the Rolling Fork River and the Little River, provided a good environment for hunting and fishing.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Settlement of Sevier County began as early as 1810 with pioneers attracted to the fertile soil of the Cossatot and Little River valleys. In an 1820 treaty, the Choctaw ceded their land east of the Mississippi River and received a tract of land in southwest Arkansas. Then, in 1825, the Choctaw signed a treaty that resulted in their being moved west of the present state line between Arkansas and Oklahoma. Governor George Izard, Arkansas’s second territorial governor, had conflicts with the Indians when the Choctaw did not accept definitions of their eastern border. Although there were reports of hostilities at other frontier outposts, some of the Choctaw returned to Arkansas to pick cotton and do farm work.

Joseph McKean and his wife, Lucy, arrived in 1833 on a steamboat that traveled up the Red River. McKean was elected as Sevier County’s representative to the first state constitutional convention in 1836 and served two terms in the Arkansas Senate. He was the first postmaster of Ultima Thule, a settlement on the east side of the present Arkansas-Oklahoma border. As a government agent, he provided supplies for the Indians during removal. Other early settlements around the county included Brownstown, Dilworth, Red Colony, Norwoodville, Falls Chapel, Ben Lomond, and Walnut Springs.

When Sevier County was created by an act of the Arkansas General Assembly on October 17, 1828, the county was much larger. It went south to the Texas state line and included parts of what are present-day Little River, Miller, Howard, and Polk counties. In 1829, the portion south of the Red River was made part of Miller County.

On October 22, 1828, the territorial legislature designated the county seat in the home of Joseph English. Five appointed commissioners located the seat of justice at a spot about one mile east of the Cossatot River. The site was called Paraclifta, reputedly in honor of a Choctaw Indian chief who intervened to resolve a dispute between some Indians and white men over a horse. The first courthouse was a log building on a public square. The territorial legislature made Paraclifta the permanent seat of justice in 1831. Maintenance of the courthouse and jail occupied much of the early county government’s attention.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The 1860 federal census recorded 7,150 white citizens in the county with 3,366 enslaved people. With thirty-two percent of the population held in bondage, the county had an economy that relied heavily on the institution of slavery. Both of the representatives from the county at the 1861 Secession Convention either owned enslaved people or belonged to an extended family that participated in the institution.

No Civil War battle was fought in Sevier County, although men supported the war effort by volunteering for various militias. During the war, Sevier County’s government received frequent requests for assistance from families who were in need because a father or son was serving in the army.

In 1867, Little River County was created from the area between the Red and Little rivers. Paraclifta, no longer centrally located, was unsuitable as a county seat, and in 1869, the county seat was moved to Lockesburg. An iron monument and an above-ground vault remain at Paraclifta.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

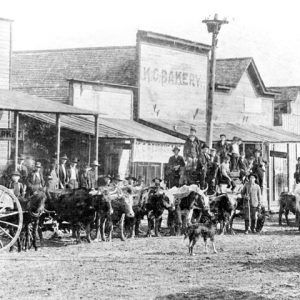

The arrival of a railroad at the end of the nineteenth century connected Sevier County to other communities and provided a way to ship timber and crops to distant markets. Arthur E. Stilwell—a Kansas City, Missouri, businessman—along with a business partner, built a belt railroad around Kansas City in 1887 called the Kansas City Suburban Belt Railroad. When Stilwell’s goal of a rail line to connect Kansas City with the Gulf of Mexico stalled in 1893 due to lack of money, he traveled to Netherlands. A Dutch coffee merchant named Jan de Goeijen helped him raise $3 million to finish the road.

In September 1897, the last gap in the line was completed linking Kansas City to the town of Port Arthur, Texas, named for Stilwell. The railroad bypassed the county seat at Lockesburg. When a route was chosen that took the road near the settlement of Hurrah City, people moved in with tents and shanties. The town was named for Stilwell’s benefactor de Goeijen, a common practice. The name was later changed to De Queen, which was easier for Americans to pronounce.

De Queen was incorporated on July 9, 1897. Jan de Goeijen visited the town that bears his name on October 8, 1897, arriving in a special rail car. When he made another trip to the town on March 10, 1927, the town greeted him with a brass band.

In 1899, a catastrophic fire destroyed fifty-four businesses in downtown De Queen. The businesses destroyed included the De Queen Bee newspaper. After the loss, a brick yard was started to rebuild the town with more fire-resistant materials.

Corn and cotton were important crops for Sevier County’s agricultural producers from the beginning, but the railroads allowed farmers to move produce to northern markets. Strawberry growers formed an association in 1898, and for several years, strawberries were the important cash crop, despite heavy losses to weather and lack of labor for harvesting. Some farmers planted peaches. Later, farmers tried cucumbers, sweet potatoes, watermelons, and cantaloupes.

Three racially motivated lynchings took place in the county in the 1880s. Three men lost their lives in 1881 after reportedly refusing to help a white man cross a creek. School teacher Oscar Jefferies was killed in 1887 after allegedly marrying a white woman. Sixteen-year-old Levi Graves died at the hands of a mob the following year after allegedly assaulting a five-year-old white girl.

Early Twentieth Century

Stilwell’s railroad was reorganized as the Kansas City Southern Railroad Company in 1900. The De Queen and Eastern, a short-line railroad, was chartered on September 22, 1900, by the Dierks family, who had bought the Williamson brothers’ timber and sawmills. They linked to the Kansas City Southern Railroad to ship lumber to Northern markets. The line was later extended east to Lockesburg and offered passenger service for a time. In 1910, the company incorporated the Texas, Oklahoma and Eastern Railroad (TO&E) starting with eight miles of track at Valliant, Oklahoma. In 1921, the TO&E was connected to the De Queen and Eastern at De Queen

After the county quorum court voted to build a new courthouse, some De Queen merchants offered to build a $10,000 building if the people of the county would vote to move the courthouse to De Queen. In a special election in 1905, De Queen won the county seat with a margin of 150 votes.

The Dierks Lumber and Coal Company’s De Queen sawmill burned in 1909, and a smaller mill and planer were rebuilt in a steel building. Dierks Forests, Inc. grew to be one of the largest forest products companies in Arkansas. The company was sold to Weyerhaeuser Company in 1969.

In addition to timber and agricultural resources, Sevier County also has various minerals, and mining was attempted in the early twentieth century to extract antimony, copper, lead, zinc, natural gas, oil, salt, and gravel. None of these mining efforts produced a boom, however, and the population of the county dropped over time as similar jobs could be found elsewhere that paid better and required less work. The Depression hit the county hard, as four of its seven banks failed, beginning with the Planter’s Bank of Lockesburg, which closed in 1929, and culminating with the Bank of Horatio, which survived until 1935. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was active in the county, building roads and providing sewing rooms, and completing structures including the Gillham School House, which is still standing and is maintained in its original condition.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The poultry industry began in the 1920s when an incubation plant was built with a capacity of 25,000 eggs. The large poultry integration companies arrived in the middle of the twentieth century, and giants Pilgrim’s Pride and Tyson Foods both established contract poultry farms in the county. Pilgrim’s Pride opened a processing plant in De Queen. Sevier County produced more than 47 million broilers in 2005.

Thirty-four men from Sevier County died while serving in the United States armed forces during World War II. Building projects after the war brought new life to the county. Millwood Dam, begun in 1961, was completed five years later at a cost of $44 million; it was dedicated December 8, 1966.

Modern Era

Agriculture and forestry continue to anchor the local economy, with timberland covering the majority of the total land area. Sevier County saw a major demographic shift in the 1990s with a wave of Hispanic immigration. Many immigrants were drawn to work offered by the poultry companies. The Hispanic population was put at 5,508, or about thirty-five percent of the total county population, in the 2020 census.

Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas (CCCUA), a two-year college of the University of Arkansas System, opened in De Queen in 1975.

The largest community in the county continues to be De Queen. Other communities in the county include Horatio and Gillham.

Attractions

Millwood Lake, a 29,500-acre Corps of Engineers lake, is located in the southeast corner of Sevier County. It is part of the flood-control system for the Red River basin and operates in conjunction with five smaller upstream lakes in the Little River Basin. Two of the upstream lakes, De Queen Lake and Dierks Lake, are in Sevier County. A third, Gillham Lake, is in nearby Howard County.

The Sevier County Historical Society maintains a museum in De Queen where artifacts of the county’s history are displayed. The museum also maintains a village of miniature replicas of some of the county’s earliest buildings.

Pond Creek National Wildlife Refuge, a 27,500-acre protected wetland, was established in 1994 to preserve one of the last remaining bottomland hardwood tracts in the Red River Basin. It provides habitat for a variety of wildlife and migratory birds and a place for visitors to observe them.

Provo Wildlife Management Area was established in 1999 on about 11,000 acres of pine and mixed hardwood timberlands owned by Weyerhaeuser Company. Wildlife management and timber management practices are integrated to provide wildlife habitat and hunting opportunities for the public.

Numerous sites in the county are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. These include Oak Grove Rosenwald School, King Schoolhouse, Gillham City Jail, and the De Queen and Eastern Railroad Machine Shop.

Famous People

Sevier County produced several political leaders who achieved statewide office. Hal L. Norwood, a native of Lockesburg, was elected as attorney general. J. Oscar Humphrey, who had both arms amputated after he was caught in a cotton gin as a youngster, became state auditor. Attorney Otis T. Wingo was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1912 and represented the state’s Fourth Congressional District. Wingo was still in office at the time of his death in 1930, and his wife, Effiegene Wingo, was appointed to fill his term, making her the second woman to represent Arkansas in Congress. Country music entertainer Collin Raye was born in De Queen. Although his family later moved to Texarkana (Miller County), where he grew up, the City of De Queen renamed U.S. Highway 70 in De Queen as Collin Raye Drive in 1992.

For additional information:

De Queen/Sevier County Chamber of Commerce. https://www.dequeenchamberofcommerce.net/ (accessed October 20, 2022).

McCommas, Betty. The History of Sevier County and Her People. Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1980.

Billy Ray McKelvy

De Queen, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Southeastern Louisiana University

Neither Tyson Foods nor Pilgrim’s Pride originally established the poultry plants in Grannis and De Queen. Tyson bought out Lane Poultry earlier and Pilgrim bought out Mountaire Poultry around 1979. I can’t remember who originally owned these processing plants, but obviously they both did end up becoming part of very large companies.