calsfoundation@cals.org

Howard County

| Region: | Southwest |

| County Seat: | Nashville |

| Established: | April 17, 1873 |

| Parent Counties: | Hempstead, Pike, Polk, Sevier |

| Population: | 12,785 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 587.33 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

9,917 |

13,789 |

14,076 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

16,898 |

18,565 |

17,489 |

16,621 |

13,342 |

10,878 |

11,412 |

13,459 |

13,569 |

14,300 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13,789 |

12,785 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

8,164 |

63.9% |

| African American |

2,642 |

20.7% |

| American Indian |

114 |

0.9% |

| Asian |

63 |

0.5% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

6 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

1,036 |

8.1% |

| Two or More Races |

760 |

5.9% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

1,517 |

11.9% |

| Population Density |

21.8 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$36,059 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$24,481 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

19.4% |

|

Howard County encompasses the Ouachita Mountains to the north and the Coastal Plain to the south. It was created in 1873 from portions of Pike, Polk, Hempstead, and Sevier counties. Nashville in eastern Howard County was the birthplace of the Dillard’s department store chain. Howard County was also the location of one of the state’s most notorious race riots.

European Exploration and Settlement

The first accounts of the inhabitants from this area come from the chronicles of the Hernando de Soto expedition in the sixteenth century. The area is known to have been inhabited by the Caddo tribe. By the mid-1800s, however, the U.S. government had relocated the Caddo to what is now Oklahoma. This area was also part of the land given to the Choctaw in exchange for property in Mississippi in the 1820s; Choctaw inhabitation of the area discouraged settlement by white people for several years.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

An important natural feature in the area that became Howard County was the Great Raft on the Red River, a tangle of trees, vines, and other vegetation that blocked the Red River for centuries. The Great Raft extended to more than 130 miles at one point, making water transportation to the great bend area difficult. This slowed the settlement of southwest Arkansas. Goods and people had to come over land from Little Rock (Pulaski County) or Camden (Ouachita County) for decades. The Great Raft was finally removed around 1838.

One of the first settlers was John Tollett, a Methodist minister from Bledsoe County, Tennessee, who first moved to the area in 1819. After scouting out the area two years earlier, Tollett decided to settle there and made arrangements to make the move to Arkansas. He purchased a boat and outfitted it, leaving port in 1819 with several families aboard, including a great number of slaves. In 1825, John Johnson erected the area’s first sawmill, on Mine Creek. The first post office was established in 1842.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The majority of Confederate enlisted men from this region were in the Nineteenth Arkansas Infantry Regiment, which fought in the Battle of Pea Ridge and the Battle of Arkansas Post.

In January 1864, a Union scouting expedition composed of 100 men of the Second Kansas Cavalry and forty men of the Sixth Kansas Cavalry passed through the county. The expedition marched toward Baker’s Springs, where Captain E. A. Barker surprised Confederate captain Williamson’s band of guerrillas, killing Williamson and five of his men, wounding two, and taking two lieutenants and twenty-five enlisted men as prisoners.

During Reconstruction, racial tension arose between African Americans and whites, and the Ku Klux Klan became more prominent. In 1868, Governor Powell Clayton put the area that became Howard County, along with several other counties in the state, under martial law and sent a militia there to keep order. This militia encountered some local resistance, resulting in what has been called the “Battle of Center Point.”

On April 17, 1873, the Nineteenth Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 57, taking townships from Hempstead, Pike, Polk, and Sevier counties to assemble Howard County. The county was named after state Senator James H. Howard. In 1905, the county seat of the area was changed from Center Point, which had suffered a devastating fire, to Nashville.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The Howard County Race Riot of 1883, which occurred on July 30, 1883, is considered one of the worst race riots in the state’s history. No one knows exactly how the riot started, though its apparent genesis was in a dispute over the surveying of property lines in Mine Creek Township in extreme western Hempstead County. Hempstead County was fifty percent African American, while Howard County was seventy-five percent white. Two African-American men, brothers Prince Marshall and James Marshall, argued with two white men, Thomas Wyatt and a man called “Montgomery.” The argument escalated into a physical fight, with the black men experiencing the worst of it. A few days later, Wyatt’s body was found mutilated with several bullet holes in it, which spurred white lawmen from Hempstead and Howard counties to form large posses of armed men and scour the countryside for his killers. A number of African Americans responded by forming their own posse. By the riot’s end, five people were dead, and forty-four black men had been arrested. Three men were hanged, and thirty-two were imprisoned. All but four men were paroled by 1890.

In the late 1880s, the railroads arrived, connecting Howard County to the rest of the state and beyond. The rails opened up markets for timber, cotton, fruits, grains, gravel, cement, wallboard, and woodchips. The county’s population continued to grow; dozens of new homes and businesses were built. By 1887, Nashville had five doctors, five preachers, and one lawyer.

Several incidents of extra judicial violence took place in the county in the late nineteenth century. Robert Norwood was lynched in 1871 for an alleged murder, while John Kirkland lost his life after being accused of being a “desperado.” The lynching of an unidentified African American man may have taken place in the county in 1894, but the details are unclear.

Early Twentieth Century

Howard County was long a major producer of cotton, and many cotton gins sprung up in the area to accommodate the vast amounts being produced. In 1919, there were four gins in Nashville and five in Mineral Springs alone. However, beginning in the early twentieth century, the cotton industry went into a decline from which it would not recover in Howard County. The last bale of cotton was ginned in the fall of 1971 at Mineral Springs.

As timber grew in importance, settlements were created to support various lumber mills in the county. Dierks, named for the owners of the Dierks Lumber Company, grew from an earlier community known as Hardscrabble.

The decline of the cotton industry had a ripple effect on the community. The county’s population peaked in 1920 and subsequently declined with each census until 1970. Along with cotton, other agricultural enterprises went into decline. For example, the number of sheep, which were kept for their wool, also decreased. In 1900, there were almost 6,500 sheep in the county; by 1930, there were no sheep at all.

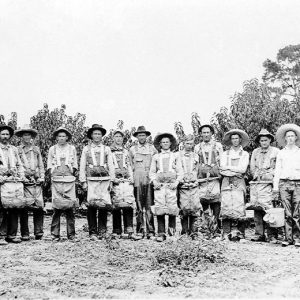

This decline, combined with the hardships of the Great Depression, made life difficult for many residents. However, peaches became a big export in the early twentieth century. The enterprises started with small farm plots having a few acres of land in the 1880s but evolved into a big-time industry by the mid-1910s. In 1915, Ozark Fruit Growers Association shipped 700 carloads of peaches. The peach industry became less prominent in the 1950s, and orchards were eventually converted from commercial ventures to “pick-your-own” operations.

The town of Tollette, located in the southwestern corner of Howard County, was incorporated as a city in 1972 but had been established by the mid-1800s, when the community was then known as Blackland Township. Around the turn of the century, Tollette was predominantly black. In the 1930s, Howard County Training School in Tollette had a variety of programs for agriculture and skilled trades, which were fostered through New Deal policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The school was destroyed by fire in 1936, and a new school was built in 1938. As of the 2010 census, the town had 240 people and was ninety-seven percent African American.

In 1938, Nashville became the home of the original Dillard’s department store, founded by William Thomas Dillard. Although the initial store was sold in the next decade and a larger establishment was developed in Texarkana (Miller County), the Nashville store was the beginning of the Dillard’s chain now based in Little Rock.

World War II through the Modern Era

During World War II, many men from the county joined the armed forces. By the 1940s, the Rural Electric Administration (REA) had arrived in many Southern towns, but it was slow to come to the rural areas like Howard County. Few places in the county had indoor plumbing, washing machines, lights, or appliances. Most people canned their own food, and many residents kept a cow and a flock of chickens. After the war, the REA finally established electrical service.

After World War II, several new industries were established in Howard County, providing jobs and boosting the economy. In Nashville, a cutlery plant opened in 1952, and it was followed by the Nashville and Howard Manufacturing Company, a clothing manufacturer. Okay Cement also established a factory in Nashville in the 1920s, as well as a company town named Okay and quarries near Millwood Lake. In agriculture, the peach industry was on the decline, but the poultry industry flourished, economically uplifting the entire county.

Howard County is home to CertainTeed Gypsum, a company that specializes in making wallboard. Many of the area’s industrial buildings offer interactive tours. The county also has lumber mills, wool mills, and a Coca-Cola bottling factory. One longtime employer has been Husqvarna, a company based in Stockholm, Sweden, which assembles weed-eaters, edgers, and blowers; however, in 2023, the company announced plans to close its factory by the end of 2024, eliminating 700 jobs.

Attractions and Notable Residents

Howard County has a great number of attractions. The Cossatot River State Park–Natural Area conserves a twelve-and-one-half-mile stretch of the Cossatot River, a southwest Arkansas stream renowned for its white-water rapids. Within the park live more than thirty rare plant and animal species, many of which are native to the Ouachita Mountains. Howard County Wildlife Management Area, representative of an Athens Piedmont Plateau habitat, includes rolling hills intensively managed for pine production and pine/hardwood mixed stands along creeks. The area is bordered on the west by Gillham Lake and the Cossatot River and partially on the south by Dierks Lake. The Nashville sauropod trackway contained thousands of tracks left by dinosaurs; most of the tracks were identified as made by sauropods. Casts of the tracks are located across the state.

Well-known residents of Howard County include former Surgeon General of the United States Joycelyn Elders, professional baseball player William Henry (Willie) Davis, actor Jimmy Wakely, and author Myra Dell McLarey.

For additional information:

Childs, Lisa C. “Forging Community in the Ouachita Foothills of Southwest Arkansas: Duckett Township, Homesteading, Distilling and Race.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4782/ (accessed April 3, 2023).

Howard County Heritage Club. The History of Howard County Arkansas. Nashville, AR: Nashville News, 1973.

———. Howard County Heritage 1988: Appreciating the Past, Anticipating the Future. Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing Company, 1988.

Lloyd, Peggy S. “The Howard County Race Riot of 1883.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Winter 2000): 353–387.

North Howard County Youth Group for Historical Research. The Unfinished Story of North Howard County. Umpire, AR: 1982.

Lauren White

Rogers, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.