calsfoundation@cals.org

Literature and Authors

Arkansas’s place in Southern American literature is partly a result of its place on the map. The eastern border, the Mississippi River, isolated Arkansas from the rest of the South, and the western border, in Indian Territory, pulled it toward the western frontier. The Arkansas River, slicing the state diagonally from northwest to southeast, further divided the region culturally and economically. Arkansas contains six natural divisions ranging from the Ozark Plateau (commonly called the Ozark Mountains) to the flat and fertile Delta on the eastern border. The combination of isolation from without and cultural diversity within its borders continues to influence Arkansas writers and writing. Even those whose association with the state is temporary or tenuous often bear the stamp of Arkansas in their work.

Arkansas’s Image in Writing

Arkansas’s geography determined its economy and its culture–and its image. The first settlers were loggers and trappers attracted by the forests and swamps of “the Creation State,” as Thomas Bangs Thorpe called it in the story “The Big Bear of Arkansas.” Once the swamps had been drained and the forests cleared, agriculture became the overwhelming source of economic development in the “Land of Opportunity,” as license plates later branded the state. For many years, industry consisted mainly of the exploitation of natural resources such as minerals and timber. There were few towns. In fact, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, nearly half the state’s population still lived in communities with a population fewer than 2,500. Consequently, the motto printed on tourism materials since 1987 is “The Natural State,” and exploitation of Arkansas’s beautiful rural isolation is an important economic resource.

The lack of a wider urban base affected intellectual and creative life in Arkansas. The scattered population could not easily support public education or other humanistic endeavors, and the old-time religion, requiring no other books than the Bible, often regarded aesthetic expression with suspicion or hostility. But traditional language arts flourished, including folk songs, storytelling, and preaching, and the state’s remoteness from the mainstream probably helped to strengthen their influence on Arkansas writing well into the second half of the twentieth century.

The earliest writings in and about Arkansas were by outsiders from as far away as Spain and France, recording sixteenth- and seventeenth-century exploration. In the nineteenth century, another spate of travel writing appeared, including the naturalist Thomas Nuttall’s journal of his travels in the Arkansas River Valley (1819); Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s description of Native Americans, early settlements, and the Ozarks (1816–1819); Washington Irving’s description in 1832 of a visit to Fort Smith (Sebastian County); and Excursions Through the Slave States (1844) by the English geologist George Featherstonhaugh, who, nearly 150 years later, turned up in a novel by Donald Harington. Friedrich Gerstäcker wrote Wild Sports in the Far West about his experiences in Arkansas soon after Arkansas gained statehood in 1836. These writers were published by and for people outside Arkansas. They created stereotypes of an Arkansas populated with indolent farmers, hapless slaves or their descendants, shiftless woodsmen, barefoot and snuff-dipping women, riverboat gamblers, and desperados.

Some of the most influential early writing in and about Arkansas is in the Southwest humor tradition. James R. Masterson, in his book Tall Tales of Arkansas (1943), defines Arkansas humor as largely oral in origin and transmission. Even printed forms of Arkansas humor were mostly ephemeral—newspapers, magazines, and pulp books. According to Masterson, traditional Arkansas humor uses exaggeration rather than understatement, explicitness rather than implication, efforts to penetrate the understanding rather than hints to challenge it. Arkansas humor has been characterized by boisterous wit, heavy satire, or the improbable. These characteristics might be applied to much Arkansas writing for the past century and a half, even that of the most literary and academic authors.

But Charles Fenton Mercer Noland was neither literary nor academic when he moved to Batesville (Independence County) in 1826 and became editor of the Batesville Eagle. He fled after fighting a duel but returned in time to carry the first Arkansas constitution to Washington in 1836. He wrote for the Spirit of the Times, a New York weekly subtitled A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage. His chief contributions were forty-five letters published over the signature of “Col. Pete Whetstone.” Like his literary descendants all over the South, he created a family, an entire neighborhood, and a culture that became the background of his stories. Hunting and sporting, especially horse racing, are his two main themes.

The Arkansas stories of the transplanted New Englander Thomas Bangs Thorpe were nationally popular and were translated into several European languages. They were collected in two volumes, The Mysteries of the Backwoods; Or, Sketches of the Southwest (1846) and Colonel Thorpe’s Scenes in Arkansaw (1858). Thorpe’s characters are typically crude and illiterate but have boundless enthusiasm for the glories of the Arkansas swamps and wildlife.

The defensive posture of Arkansas people is in part a reaction against so many jokes in these early books and the state’s newspapers. At a meeting of newspaper editors in Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1878, William Quesenbury, writer and cartoonist for the Fayetteville (Washington County) Southwest Independent, read his poem, “Arkansas,” in which he asks:

What stigma rests on Arkansas?

What crime or foul disgrace upon her?

Where is the hand would dare to draw

A black line on her shield of honor?

His answers to these questions are much the same in the twenty-first century, when the questions are still being asked, though not in tetrameter stanzas: The Mississippi River and the Ozark Mountains made Arkansas much less accessible to immigration than other parts of the continent. And when immigrants began to settle in Arkansas, they were not from the best society but included many who had already failed or transgressed elsewhere. They did not develop loyalty to the state but rather, as in the Quesenbury poem, claimed their old home: “No, me and Jack was born out here, / But daddy come from Indianer.” Quesenbury maintains that textbooks do not teach the real Arkansas and that people who go to Arkansas to make their living are all too willing to slander the state when they return home. These complaints are still alive in Arkansas, where regular attempts have been made to promote teaching Arkansas history to counteract what is felt to be the state’s inferiority complex.

Arkansas Newspapering

The natural evolution from Noland, Thorpe, and their ilk was toward publication for readers within the state. The scattered population could not support a book-publishing culture, but this circumstance encouraged the development of newspapers, whose importance in the state’s cultural life cannot be overestimated. The Arkansas Gazette was first published by William Woodruff at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), the territorial capital, on November 20, 1819, the same day as the territory’s first election. Woodruff is an Arkansas icon, and his entrance into the territory, poling two pirogues lashed together bearing his printing press, is part of Arkansas mythology. Within its first month, the Gazette contained the spirited and opinionated letters that were so much a part of its influence and popularity in the state. When Little Rock (Pulaski County) became the capital, it had a population of 600 and a public press consisting of three newspapers: the Arkansas Gazette, the Arkansas Advocate, and The Times. Between 1819 and 1993, more than 2,500 newspapers were published in Arkansas. They were often the only outlet not only for writers of news and opinion but for columnists, poets, and anyone else with something to put before the public.

Opie Read was a reporter for The Prairie Flower of Carlisle (Lonoke County), the Gazette, and other papers, but his reputation is due to The Arkansaw Traveler, a paper that first appeared in 1882, purporting to expose the hicks of the backwoods for the amusement of citified Little Rock readers. The Traveler quickly achieved a circulation of 85,000. His description of Arkansas “characters” drew local resentment, but, even after he moved to Chicago, Illinois, his paper was a national institution.

Many twentieth-century Arkansas writers honed their skills and acquired their readership in the Gazette, the Arkansas Democrat, and other newspapers in the state. Their columns, stories, humor, and verses have frequently been reprinted as books. Throughout the years, the “Arkansas Traveler” column in the Gazette had excellent and sometimes hilarious writing from Ernie Deane, Bob Lancaster, Mike Trimble, and Charles Allbright. Paul Greenberg, Gene Lyons, Ernie Dumas, Robert McCord, and others produced outstanding reporting, investigative pieces, and commentary, some of it later published as books. Some of Lancaster’s pieces for the Arkansas Times, a magazine-turned-newspaper that welcomed some of the Gazette staffers after that daily closed, evolved into The Jungles of Arkansas: A Personal History of the Wonder State (1989). Charles Portis, a reclusive but brilliantly funny novelist, worked on the Memphis, Tennessee, Commercial Appeal, the Arkansas Gazette, and the New York Herald Tribune before returning to Arkansas to write books. Writers of that generation are generally far from the Arkansas boosterism of their predecessors, but their criticism is more acceptable because they are perceived as locals.

Other writers have used Arkansas magazines and newspapers as their creative outlet, including Robert Wynn for his historical pieces and memoirs of the Boston Mountains, and Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni, Marie Rushing, and many others for their poetry. Otto Ernest Rayburn published several magazines extolling the “Anglo-Saxon seed-bed,” which led to his Ozark Country (1941). The move of the Oxford American magazine to central Arkansas in 2002 provided another outlet of considerably more sophistication than Rayburn’s Arcadian Life. The many denominational newspapers, including the Arkansas Catholic, have supplied a vehicle for theological debate and religious or inspirational writing.

Arkansas in Memoir

Bearing out the contention that Arkansans like stories better than any other writing, memoir and autobiographical writing comprise perhaps the most impressive body of Arkansas literature. The authors are black and white, male and female, rich and poor, celebrated and obscure. Wayman Hogue, in Back Yonder, An Ozark Chronicle (1932), combines his personal reminiscence with a systematic treatment of the hill culture. Hogue’s daughter Charlie May Simon, a writer of biographies for younger readers, wrote two memoirs, Straw in the Sun (1945), recounting her return to backwoods Arkansas to become a writer, and Johnswood (1953), the story of her life with the poet John Gould Fletcher, himself the author of Life is My Song (1937). Otto Rayburn’s Forty Years in the Ozarks (1957) celebrates a life of writing and publishing. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), the most Arkansas-connected of her books, recounts her childhood years in the general store in Stamps (Lafayette County). Brooks Hays’s memoir, A Hotbed of Tranquility (1968), describes his careers in the Southern Baptist Convention and the Arkansas Democratic Party. The Little Rock desegregation crisis spawned a host of memoirs, notably those of Daisy Bates, Melba Pattillo Beals, Elizabeth Huckaby, Terrence Roberts, and Orval Faubus. Actor Ben Piazza’s fictionalized autobiography, The Exact and Very Strange Truth, was published in 1964. Shirley Abbott wrote two volumes about her family in Hot Springs, Womenfolks (1983) and The Bookmaker’s Daughter (1991). Margaret Jones Bolsterli, a professor at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville, wrote Born in the Delta: Reflections on the Making of a Southern White Sensibility (1991). Looking for Hogeye (1986) recounts the return of New York Times reporter Roy Reed, another Gazette alumnus, to his home state. Coal to Diamonds: A Memoir (2012) was written by Beth Ditto, singer and songwriter for the band Gossip. Ditto wrote about, among other things, growing up poor in Judsonia (White County). Garrard Conley, who grew up in northern Arkansas, wrote his 2016 memoir Boy Erased about his experiences at the Memphis, Tennessee, “ex-gay” therapy program Love in Action.

Multi-Faceted Arkansas Authors

Bernie Babcock was one of the first Arkansas women to support herself by writing. She started out at the Arkansas Democrat as a book reviewer and editor of the society page. In 1906, she started an illustrated magazine, The Arkansas Sketch Book. In 1917, she became the first Arkansas member of the National League of American Pen Women. She published more than forty novels, including temperance stories and treatments of the Lincoln and Lee myths. The Soul of Ann Rutledge (1919) was an international bestseller and went through fourteen printings. Babcock also wrote The Man Who Lied on Arkansas and What Got Him (1909) and worked on the WPA Writers Project, supervising the collection and transcription of the slave narratives.

Hogeye (Washington County) is the setting of a novel, Acres of Sky (1930), by Charles Morrow Wilson. He also edited Ozark Fantasia (1927) by Charles J. Finger. After he left Fayetteville, Wilson wrote chiefly nonfiction books about the tropics, but he also produced a collection of tales, The Bodacious Ozarks (1959). Finger was a transplanted English globetrotter who published a magazine, All’s Well, from a farm outside Fayetteville and worked on the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Writers Project that produced the Guide to the State (1941). Finger also wrote fiction for young readers and a memoir, Seven Horizons (1930).

Wabbaseka (Jefferson County) native Eldridge Cleaver, who was a leader in the Black Panther Party in the 1960s, published several books, including the autobiographical titles Soul on Ice (1968) and Soul on Fire (1978), Eldridge Cleaver: Post-Prison Writings and Speeches (1969), and Eldridge Cleaver’s Black Papers (1969).

Helen Gurley Brown of Green Forest (Carroll County) spent decades at the helm of Cosmopolitan magazine as editor-in-chief and was the author of many books, including the bestselling Sex and the Single Girl (1962).

Arkansas in Fiction

It is not a long stretch from the personal narrative and the memoir purporting to be true to narrative fiction. It is probably safe to say that most Arkansas writers have aimed at telling a good story rather than subscribing to any literary or artistic school. Some elements of Southern storytelling are evident in Arkansas fiction from early on and are still evident. There is often a strong sense of place—small towns and rural settings especially. The characters represent a cross-section of Arkansas population—white, black, working class, plantation aristocrats and nouveau-riches, and lots of garrulous narrators. Arkansas had at least two successful practitioners in the nineteenth-century heyday of American local-color fiction. Ruth McEnery Stuart, a New Orleans, Louisiana, woman who married a farmer from Washington (Hempstead County), wrote stories for Harper’s and other national magazines between 1888 and 1913. Washington became her fictional village Simpkinsville, whose residents spoke the dialect of the Arkansas plain folk, dipped snuff, and espoused the gentle and genteel beliefs of mid-South Protestantism. Alice French was a transplanted New Englander, daughter of a Midwestern businessman. In her middle age, she wintered in northeastern Arkansas, where she wrote, under the name Octave Thanet, stories of a grittier Arkansas life of trappers and squatters along the cypress swamps, as well as of cavalier planters and their family secrets. In her Arkansas stories, French wrote from a patronizingly aristocratic point of view familiar to Arkansans and emphasized the more squalid hues of local color, but she also made a serious effort to reproduce the language of her region. In the 1880s, she wrote a series of nonfiction magazine pieces for The Atlantic Monthly about several Arkansas towns, including Hot Springs and Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

For much of the twentieth century, many Arkansas writers left home to make their reputations, or occasionally to make money. Although their detachment from Arkansas led eventually out of regionalism into a generic American fiction, their work often used elements of Southern and Arkansas life. Thyra Samter Winslow left Fort Smith for New York, where she published more than 100 pieces in the Smart Set between 1915 and 1923, as well as stories in Redbook, Cosmopolitan, and The New Yorker. Her depiction of small-town life, with mean-spirited, conventional characters in run-down neighborhoods or stuffy country clubs, contains many details drawn from her early experience in Arkansas. Some of these were collected in 1935 in My Own, My Native Land.

Another Arkansan who went to New York, David Thibault of Little Rock, published stories in Collier’s Magazine between 1928 and 1931, most of them devoid of Arkansas connections. But he also had nearly completed a novel, Salt for Mule, set on a Delta plantation, when he died; it was never published, though several chapters appeared in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1937.

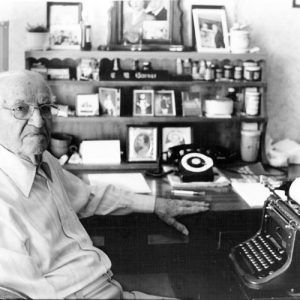

One of author Charles Portis’s characters says, “A lot of people leave Arkansas and most of them come back sooner or later. They can’t quite achieve escape velocity.” Among others, Roy Reed, Douglas Jones, and Dee Brown retired to Arkansas after careers elsewhere. Jones created a notable body of historical fiction about the American West. Some of his work is set in northwestern Arkansas and the adjacent Indian Territory, including Elkhorn Tavern (1980) and Weedy Rough (1981). Brown wrote more than a dozen historical works, including the novels Creek Mary’s Blood (1980) and They Went Thataway (1960). He wrote historical nonfiction, such as the much-acclaimed and much-translated Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (1970). Brown also wrote for young readers, including Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow: Railroads in the West, which received an award from the Western Writers of America in 1981 for the best western for young people.

Portis is himself a returned Arkansan, resettling in the state after working on the New York Herald Tribune. Many readers recall True Grit (1968) as a western with a historical setting straddling the Arkansas boundary in what was then Indian Territory, in which Portis makes splendid comic use of the Wild West material. Portis, who has been called America’s “least-known great writer,” represents a brilliant Arkansas incarnation of Old Southwest humor. Most of his fiction is set in our own time, populated with off-beat characters so beloved of earlier writers and some of Portis’s contemporaries—adherents of mystical religion, dropouts, “the world’s smallest perfect man,” and Joann the Wonder Hen.

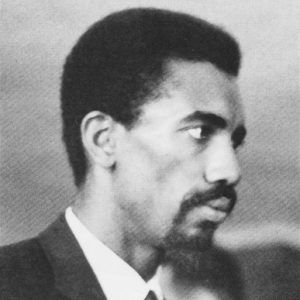

Arkansas writers in the last decades of the twentieth century made use of an Arkansas where mobile homes and shopping malls replaced fields and forests. Their sense of place included attention to local language, customs, and especially characters, and often these elements are links to or evolutions from the past. Mary Elsie Robertson’s first collection of stories, Jordan’s Stormy Banks (1961), draws on her roots in Charleston (Franklin County), hometown of Dale Bumpers and several other celebrated Arkansans. These include the novelist Francis Irby Gwaltney, author of A Step in the River (1960) and other novels portraying the New Southerner struggling to understand the changes in his way of life. Henry Dumas (1934–1968), an African-American writer born in Sweet Home (Pulaski County), became something of a cult figure after a New York policeman killed him in “a case of mistaken identity.” Some of his work was published posthumously in anthologies of black writers and also under his name, including Goodbye, Sweetwater: New and Selected Stories (1988) and Echo Tree: The Collected Short Fiction of Henry Dumas (2003). Richard Ford, whose Independence Day received the Pulitzer Prize, spent his summers with his grandfather in the Marion Hotel in Little Rock, but he moved on, both physically and artistically, to other scenes.

Some writers—such as the western writer Cynthia Haseloff and the romance writer Velda Brotherton—have remained physically in Arkansas but work in mainstream American modes. When Jack Butler lived in Little Rock, he wrote Living in Little Rock with Miss Little Rock (1993), an American blockbuster. Narrated by the Holy Spirit, it centers on a millionaire lawyer and his wife and obliquely includes the Arkansas creation-science trial, McLean v. Arkansas. Joan Hess, Charlaine Harris, and Grif Stockley created Arkansas characters in crime fiction, and John Grisham recalled his childhood in northeastern Arkansas in the bestselling novel A Painted House. Ellen Gilchrist and William Harrison became successful writers while living in Arkansas, but they rarely refer to this background in their work.

Some of Donald Harington’s work bears the Southwest-humor stamp of his artistic forebears. But, at his best, he represents a high point in working as a contemporary writer who happens to use traditional Ozark materials. He created his own place, Stay More, home of the Stay Morons, who recur throughout his fiction. Some of his novels, particularly The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks (1975), use the traditional elements, such as the tall tale and the bawdy joke, with a modern sensibility. Harington’s nonfiction work, Let Us Build Us a City: Eleven Lost Towns (1986), combines personal reminiscence with local history, a blend that is particularly appealing to Arkansans.

Arkansas Poetry

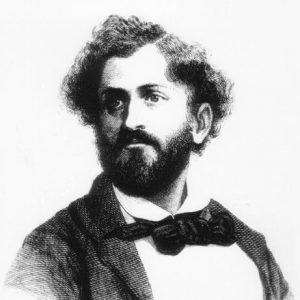

As throughout the South, nineteenth-century poetry in Arkansas was largely in the Romantic and Victorian veins. One early poet, Boston, Massachusetts–born Confederate general Albert Pike, wrote technically competent verses from his vast knowledge of the arcane mythology of Freemasonry. His Prose Sketches and Poems, Written in the Western Country (1834) preceded the obligatory “Letters from Arkansas,” published in the American Monthly Magazine in 1836. The list of published poets until well into the twentieth century runs heavily to Civil War veterans and pious ladies, many of whom attended meetings of the Poets’ Roundtable, the Arkansas Writers’ Association, the Ozark Writers and Artists Guild, and other groups, sometimes alongside other more accomplished writers. Their works were published privately or in newspapers (especially the sectarian press), and popular magazines of the time, and generally their reputations were local or regional. One notable exception is George Ballard, a black poet who published in Fayetteville newspapers. A few small presses and newspaper publishers turned out books of poetry, notably the Bar D Press of Siloam Springs (Benton County) in the 1930s.

Governor Ben Laney proclaimed Arkansas Poetry Day in 1948, but it lapsed afterward. In 1963, the Arkansas General Assembly enacted Poetry Day legislation, ordering it to be observed every October 15. The legislature established the position of poet laureate in 1923. The post is filled by the governor. Nominees generally have been from the popular and confessional rather than the high-culture end of the literary spectrum. The first was Charles Davis of the Gazette staff, followed by Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni of Fayetteville, author of many volumes of verse and a promoter of poetry clubs and magazines. Next came Lily Peter of Marvell (Phillips County), another of Arkansas’s great female personalities—farmer, environmentalist, teacher, and poet. Poet laureate Verna Lee Hinegardner of Hot Springs was appointed in 1991. Hinegardner invented a poetic form called the minute, consisting of sixty syllables in rhyming couplets with a syllabic line count of 8,4,4,4–8,4,4,4–8,4,4,4. Peggy Vining was appointed laureate in 2003, followed by Jo McDougall and Suzanne Underwood Rhodes.

John Gould Fletcher was arguably the only Arkansas writer until the late twentieth century whose life and work showed any connection with the wider literary world. Although he was proud of his Southern heritage, he lived for more than twenty years in Europe, where he participated in various Modernist movements, especially Imagism, before returning to Little Rock to take up regionalism and folklore. Fletcher’s Breakers and Granite (1921) includes “Songs of the Arkansas.” He also wrote an impressionistic history of the state, Arkansas (1947), as well as a memoir, Life is My Song (1937). For his Selected Poems (1938), he received the Pulitzer Prize.

After the 1950s, instances of poetry as a craft and an art, rather than an effusion of sentiment, began to occur more frequently. One reason, aside from the changes in taste and education in the country, was the creative writing program at the University of Arkansas, founded in 1965 by James Whitehead and William Harrison. They soon were joined by Miller Williams, one of the best-known Arkansas poets, especially after his appearance at President Bill Clinton’s second inauguration. Both he and his predecessor at Clinton’s first inauguration, Maya Angelou, used the imagery and language of rural Arkansas with considerable success. Both traveled extensively, but, unlike Angelou, Williams remained a rooted Arkansan, though the forms of his poetry came from many other traditions and languages. Williams’s contribution to writing in Arkansas included his service as director of the University of Arkansas Press, which encouraged the publication of scholarly and academic writing as well as the works of a few practitioners of the belletristic arts, notably Ellen Gilchrist. The UA Press published Gilchrist’s first book of fiction, In the Land of Dreamy Dreams, in 1981. Victory over Japan, her second collection of short stories, won the 1984 National Book Award for fiction. Like others, Gilchrist is claimed by more than one state, including her native Mississippi. The press also published an early volume of the work of popular poet Billy Collins.

Other poets emerged later in the twentieth century. C. D. (Carolyn) Wright received her MFA at UA, taught at Brown University, and was named state poet of Rhode Island. Nevertheless, she often worked out of her Ozarks background. In 1994, she compiled an anthology and traveling exhibition, The Lost Roads Project, celebrating Arkansas writing. One poet in the project, virtually unknown to Arkansas and the world, was besmilr brigham of Horatio (Sevier County), whose lower-case signature belies a commanding if obscure gift. Lost Roads Publishers issued a selection of her poems, Run Through Rock (2000). The title of Wright’s project was an homage to Frank Stanford, Wright’s collaborator in an earlier project, Lost Roads Publishers. Before his suicide in 1978, Stanford published nine books of poetry full of knives, hogs, privies, and death. The UA Press published The Light the Dead See: Selected Poems of Frank Stanford in 1991, edited by Leon Stokesbury, another alumnus of UA’s creative writing program.

Jo McDougall’s poetry draws on her life on a farm in the Arkansas Delta. Andrea Hollander, who was writer-in-residence at Lyon College in Batesville (Independence County), like McDougall a prize-winning poet, writes with an ease that belies the skill and sensitivity of her poems. Ralph Burns, former editor of the literary journal Crazyhorse, is a widely published, prize-winning poet.

Poet Bryan Borland, who was born in Dumas (Desha County), is the founding editor of Assaracus: A Journal of Gay Poetry and of Sibling Rivalry Press, which champions LGBT authors but publishes a wide range of literature. His poetry collections include Less Fortunate Pirates: Poems from the First Year Without My Father (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2012) and DIG (Stillhouse Press, 2016).

Arkansas Children’s Books

Some Arkansas authors from early on have written children’s books. Charles J. Finger’s greatest fame came in this area, where he received the prestigious Newbery Medal of the American Library Association for Tales from Silver Lands (1924). Faith Yingling Knoop of Little Rock wrote historical books for young readers, including a series on explorers such as Amerigo Vespucci, Coronado, Balboa, and Sir Edmund Hillary. Charlie May Simon was another prize-winning biographer for young readers. Her subjects included Albert Schweitzer, Andrew Carnegie, and Crown Prince Akihito of Japan. Simon also wrote children’s fiction, much of it with an Arkansas setting and characters. Mary Medearis wrote Big Doc’s Girl in 1942 out of her own family’s life in Argenta (now North Little Rock in Pulaski County). For a time, Lois Lenski lived in northeastern Arkansas, where she wrote Cotton in My Sack (1949), one of a series of regional stories for children. She received a Newbery Medal for Strawberry Girl (1946), and two other works were named Newbery Honor Books. Thomas J. Dygard, a journalist at the Gazette and the Associated Press in his main career, also wrote nearly a dozen sports novels for juveniles, from Running Scared (1977) to Running Wild (1996).

Crescent Dragonwagon, while she lived in Arkansas, combined her career as innkeeper and writer of cookbooks with a steady production of children’s stories in prose and verse. Bette Greene grew up in Parkin (Cross County) and lived for many years in Memphis. Her book Philip Hall Likes Me. I Reckon Maybe (1974) was named a New York Times Outstanding Book of the Year and a Newbery Honor Book. Her novel The Summer of My German Soldier (1973) inspired an Emmy Award–winning television film. Robbie Branscum wrote twenty books for children. She drew on her own childhood near Big Flat (Baxter County) for her first book, Me and Jim Luke, published in 1971. Her books tackle big topics for juveniles, including runaways, incest, and murder. The Murder of Hound Dog Bates received the 1983 Edgar Award for the best young adult mystery book. Otto Salassi wrote a few books for young readers, including one that was translated into Danish. On the Ropes (1981) was selected by the American Library Association as one of the outstanding books for young adults.

Trenton Lee Stewart, born in Hot Springs, is a contemporary novelist and short-story writer. He is best known as the author of The Mysterious Benedict Society series, a trilogy of bestselling young adult novels. Stewart’s The Extraordinary Education of Nicholas Benedict was published in 2012 by Little, Brown; the author acknowledged that it is a prequel of sorts to the Mysterious Benedict Society series but said it stands alone and is not technically part of the series. The Secret Keepers, a young adult novel not in the Mysterious Benedict series, was published in September 2016 by Little, Brown. Additionally, Stewart’s stories have been published in a number of literary magazines, including the Virginia Quarterly Review.

Literature in the Arkansas Community

The Arkansas Writers’ Conference (AWC), which begun in 1944, is an annual two-day conference and workshop for writers and editors of all genres from across the state and beyond. The Arkansas Pioneer Branch of the National League of American Pen Women continues to sponsor the conference in the twenty-first century.

The Six Bridges Book Festival (previously called the Arkansas Literary Festival or Lit Fest), held annually in April, was started by Arkansas Literacy Councils, Inc., (ALC) in 2002, and the Central Arkansas Library System took over management of the Little Rock–based festival in 2008.

The C. D. Wright Women Writers Conference, held at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway (Faulkner County), was established in 2017 to recognize, promote, and encourage women writers, with a special emphasis on writing inspired by or written in the South. It is named in honor of Arkansas poet C. D. Wright.

Arkansas Literature’s Past—and Future

The much-discussed “sense of place” that was a hallmark of Southern writing, including Arkansas writing, began fading away amid the onslaught of television and other mass media that had a leveling effect on American life, language, and culture. Another influence is mobility: No longer is it taken for granted that children grow up at their granny’s knee, listening to the aunts, uncles, and cousins and absorbing almost by osmosis the vocabulary and stories of the family and community. Furthermore, and sadly for Arkansas, there is no longer the variety of statewide newspapers that existed until the late twentieth century. Instead, there is essentially one state newspaper alongside networks of essentially local or regional papers, some of them owned by national conglomerates whose interests do not include perpetuating old stories and humoring cranky letter writers. Nevertheless, Arkansas storytelling has had its days of glory and will be carried forward in various forms by future generations.

For additional information:

Bain, Robert, and Joseph M. Flora, eds. Contemporary Poets, Dramatists, Essayists, and Novelists of the South: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994.

Baker, William M., and Ethel C. Simpson. Arkansas in Short Fiction. Little Rock: August House Publishers, 1986.

Contemporary Arkansas Authors: A Selective Bibliography. Little Rock: Department of Arkansas Natural and Cultural Heritage, 1982.

Dougan, Michael B. Community Diaries: Arkansas Newspapering, 1819–2002. Little Rock: August House, 2003.

Dougan, Michael B., Tom W. Dillard, and Timothy G. Nutt, compilers. Arkansas History: A Selected Research Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995.

Howerton, Phillip Douglas, ed. The Literature of the Ozarks: An Anthology. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

Razer, Bob. “Arkansas Authors.” Recurring review column in Arkansas Libraries. Little Rock: Arkansas Library Association.

Shores, Elizabeth Findley. Shared Secrets: The Queer World of Newberry Medalist Charles J. Finger. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Wright, C. D. The Lost Roads Project: A Walk-In Book of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

———. “The Poetic History of Arkansas.” Poets.org. https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/poetic-history-arkansas (accessed June 29, 2023).

Ethel C. Simpson

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

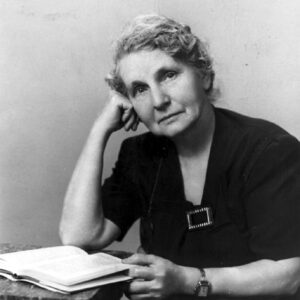

Shirley Abbott

Shirley Abbott  Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou  Katharine Anthony

Katharine Anthony  Bernie Babcock

Bernie Babcock  Daniel Black

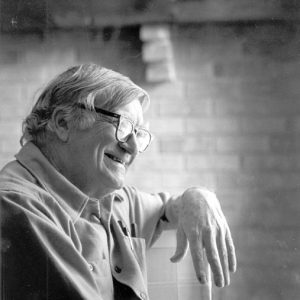

Daniel Black  Dee Brown

Dee Brown  Come and Get It

Come and Get It  Ernie Deane

Ernie Deane  Connie Dover

Connie Dover  Henry Dumas

Henry Dumas  Charles Finger

Charles Finger  John Gould Fletcher

John Gould Fletcher  Alice French

Alice French  Claud Garner

Claud Garner  Friedrich Gerstäcker

Friedrich Gerstäcker  Ellen Gilchrist

Ellen Gilchrist  Francis Gwaltney

Francis Gwaltney  E. Lynn Harris

E. Lynn Harris  Andrea Hollander

Andrea Hollander  Faith Yingling Knoop

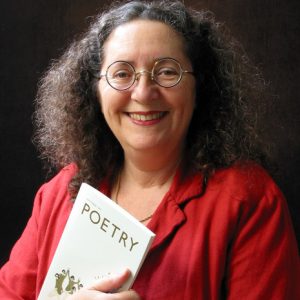

Faith Yingling Knoop  Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni

Rosa Zagnoni Marinoni  Jo McDougall

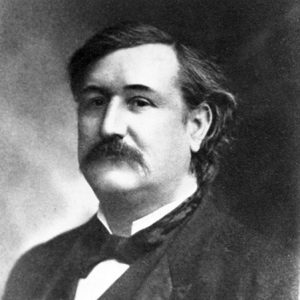

Jo McDougall  Fent Noland

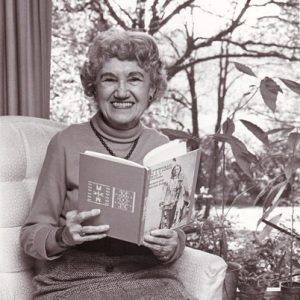

Fent Noland  Lily Peter

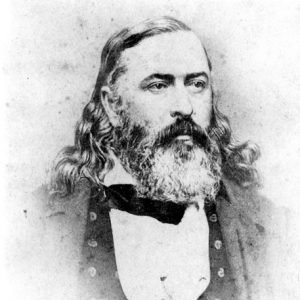

Lily Peter  Albert Pike

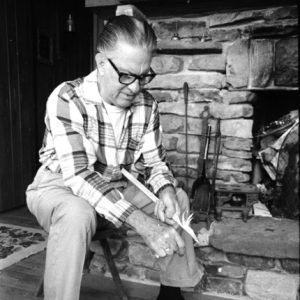

Albert Pike  Otto Ernest Rayburn

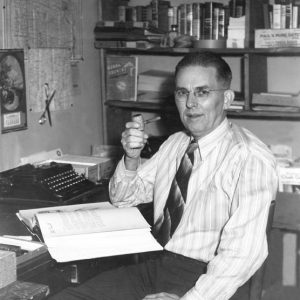

Otto Ernest Rayburn  Opie Pope Read

Opie Pope Read  Roy Reed

Roy Reed  Dusty Richards

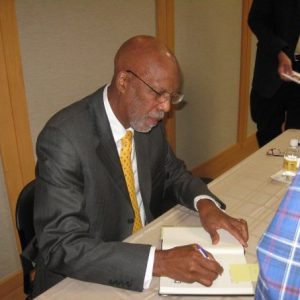

Dusty Richards  Roberts Book Signing

Roberts Book Signing  Charlie May Simon

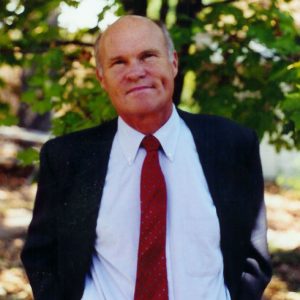

Charlie May Simon  Grif Stockley Jr.

Grif Stockley Jr.  Ruth Stuart

Ruth Stuart  David Thibault

David Thibault  Charles Morrow Wilson

Charles Morrow Wilson  William Woodruff

William Woodruff

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.