calsfoundation@cals.org

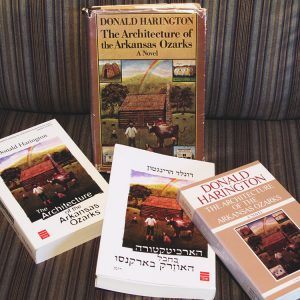

The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks

“We begin with an ending.” The first sentence of Donald Harington’s 1975 novel The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks imagines time as a circle, and the story it begins as an experiment in narrative art.

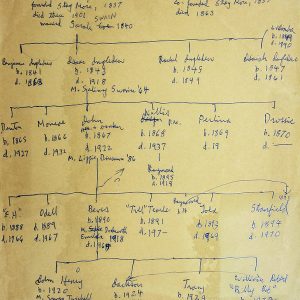

For his fourth published novel, and the third in the Stay More saga, Harington adopted an expansive perspective, spanning some 140 years of the life of his fictional Ozarks town. Partly inspired, according to the author, by Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realist novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, Architecture would serve as the Bible of Stay More. Divided into twenty chapters that proceed through the lives of some six generations of the Ingledew family, the first European American settlers in Stay More, Architecture looks both backward to the two previous Stay More novels, Lightning Bug (1970) and Some Other Place. The Right Place. (1972), and forward to novels that Harington would not write for many years, including Butterfly Weed (1996), When Angels Rest (1998), Thirteen Albatrosses, or Falling Off the Mountain (2002), The Pitcher Shower (2005), and Enduring (2009). In interviews, the author sometimes pooh-poohed his ability to keep straight all of the names and relations of the generations of Stay Morons (as he called them) whom he had brought to life over the decades, but one of the joys of Architecture is to recognize the innocent previews that it provides for stories he would not tell in detail for many years.

Architecture begins with the arrival of Jacob Ingledew and his brother, Noah, in the remote Ozarks region and ends, nineteen chapters and more than a century later, with the last Ingledew, Baby Boomer Vernon, who will come of age as the town of Stay More is dying out in the aftermath of World War II. Along the way, Harington involves Jacob’s descendants in many of the notable historical and cultural developments of the nation, from the Trail of Tears and the Civil War to Reconstruction, the Gilded Age, both world wars, Prohibition, and the Great Depression. As secluded as it is, Stay More finds itself dealing with the bizarre magic of early photography, the advent of factory production, the literal intrusion of the “horseless carriage,” and the invention and rapid conquest of television. Over and over again, Stay More both reproduces and resists, in its rustic, homespun fashion, these and other notable trends that swept through the United States at large.

For example, Harington literalizes the cliché of the Civil War being “brother against brother” by pitting Stay More’s co-founders, Jacob and Noah Ingledew, against each other in a firefight at the close of the Civil War chapter. Jacob has enlisted with the Union, but Noah, a reclusive, lifelong bachelor, has taken up with the Confederacy after allowing himself to be “recruited” (a term that Harington has considerable fun with) by a woman named Virdie Boatwright, who shows up early in the chapter touring the region on behalf of the rebels in her “cat wagon,” the first “mobile home” in the Ozarks. Expert hunters with no ammunition to waste, Stay Morons make superb marksmen. But given that they are also shy and inclined to be friendly to a fault, they have refused, even in the midst of war, to shoot to kill. So when the author brings Jacob and Noah face to face toward the end of the war, it is only thanks to a signature Haringtonian joke that the result proves fatal. Facing his older brother, who is wearing the enemy’s uniform, Noah instinctively utters his favorite cuss word, the second syllable of which (“fire”) becomes a pun, a command that startles Jacob’s horse at just the wrong moment. One brother is shot in the shoulder, while the other is shot through the heart. The comic but deadly duel of Jacob and Noah Ingledew serves to elevate the brother-against-brother cliché to the level of an actual tragedy, a man dying at the hand of his own brother, who will be haunted by his deed for the rest of his life.

Stay More both fulfills and departs from well-known American history in other ways as well. Take, for example, the arrival of religion. Harington’s Stay Morons are respectful and friendly to evangelists, but they are also congenitally independent, so none of the many preachers who come through the area ever manages to keep the locals interested and attending. Only after all of the mainstream denominations have failed is Stay More visited by a huge man named Long Jack Stapleton, who arrives in a bearskin coat to deliver bracingly real picture shows (or “pitcher shows,” as Stay Morons pronounce it) of select Bible stories that both tantalize and scandalize the enrapt audience. Brother Stapleton is the only preacher who is welcome to stay, and he becomes a fixture at Stay More funerals, projecting the life stories of the deceased at the graveside service even as the rest of the town sings the Stay More anthem, “Farther Along,” a remarkably agnostic hymn.

To narrate the story of Stay More’s uniquely comedic relationship to the larger sweep of American history, Architecture is told by an adult version of the young Dawny Harington who shows up, in one way or another, in all of Harington’s books. But Architecture is the only one narrated by Professor Harington in teaching mode, delivering a course on vernacular architecture. The frontispiece of each chapter is a drawing, by the author, of a building associated with a specific timeframe in the story of the Ingledews and Stay More. Each chapter includes professorial commentary on the style and the structure of the building as indices of the way of life in Stay More in the period covered by the chapter. The lectures provide both a framework and a pretext for tracing the history of Harington’s town, always with an emphasis on the non-linearity of the developments of life.

The most striking theme of these architectural lessons is the ubiquity of bigeminality, the idea that no building’s structure is unitary, but is achieved in conjunction with a duple, an other, a companion that completes it. For example, when Jacob early in the book marries young Sarah Swain in a ritual based on the Osage custom for uniting a couple, he soon finds that the log cabin he and Noah have built for (and carefully divvied up between) themselves simply will not work for married life. So he constructs the first two-part log cabin, one side for him and one for his new wife, joined by a “dog trot” area. In Stay More, each whole is naturally dialogic, achieved only in constant, vital conversation with another, as Professor Harington demonstrates again and again in his lectures and asides.

The essence of doubling and coupling into new wholes is also realized in Harington’s nickname for his fourth novel. Throughout his career, Harington crafted titles that would lend themselves to three- or four-letter abbreviations. (He usually referred to his first novel, The Cherry Pit, as “PIT” and his second novel, Lightning Bug, as “BUG,” for instance.) But only one of his fifteen novels had a perfectly balanced duple of a nickname: Architecture’s TAOTAO. The suggestion of the yin-yang, two separate areas of light and dark intertwined with and punctuating each other in a perfect circle, serves as an inexhaustible metaphor for the stories that make up Architecture. Patriarch Jacob Ingledew improbably becomes governor of Arkansas during the Reconstruction era, and the last Ingledew, Vernon, will run for governor of the state in the final chapter of Architecture (and, eventually, in much greater detail in Harington’s 2002 novel Thirteen Albatrosses, or Falling Off the Mountain), creating a historical loop that encloses the first and the last Ingledews of Stay More within their political endeavors.

In interviews, Harington said that the chief challenge of writing Architecture was to keep it lively within the framework of the lectures on architecture, forcing him to make it (in his estimation) his funniest book. The American Library Association named Architecture one of the Ten Best Novels of 1975, and folklorist Vance Randolph declared it the “best Ozark novel” he had ever read. Nevertheless, the pattern that had been established with his first three novels held: despite generally favorable reviews, the book did not sell well enough to cover the author’s advance. In this case, its commercial failure contributed, in Harington’s telling, to the trauma of a series of ruptures in the author’s life (including the death of his father, the end of his first marriage, and the folding of the college where he had been teaching for many years) that would keep him from publishing another book for more than a decade. In fact, as the author told it, the book’s lack of commercial success even prompted his editor to resign from Little, Brown, and caused Harington to develop a severe drinking problem. The book that Harington began with an ending stood, for quite a long time, as a real ending.

For additional information:

Harington, Donald. The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1975.

Heller, Amanda. “Review of The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks.” The Atlantic, January 1976. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1976/01/the-architecture-of-the-arkansas-ozarks/662796/ (accessed September 24, 2025).

Brian Walter

St. Louis, Missouri

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.